Planning Nursing Care

Objectives

• Explain the relationship of planning to assessment and nursing diagnosis.

• Discuss criteria used in priority setting.

• Discuss the difference between a goal and an expected outcome.

• List the seven guidelines for writing an outcome statement.

• Develop a plan of care from a nursing assessment.

• Discuss the process of selecting nursing interventions during planning.

• Describe the role that communication plays in planning patient-centered care.

Key Terms

Collaborative interventions, p. 242

Consultation, p. 249

Critical pathways, p. 247

Dependent nursing interventions, p. 242

Expected outcome, p. 238

Goal, p. 238

Independent nursing interventions, p. 242

Interdisciplinary care plans, p. 244

Long-term goal, p. 239

Nursing care plan, p. 244

Nursing-sensitive patient outcome, p. 240

Patient-centered goal, p. 239

Planning, p. 236

Priority setting, p. 237

Scientific rationale, p. 245

Short-term goal, p. 239

![]()

Tonya conducted a thorough assessment of Mr. Jacobs’ health status and identified four nursing diagnoses: acute pain related to incisional trauma, deficient knowledge regarding postoperative recovery related to inexperience with surgery, impaired physical mobility related to incisional pain, and anxiety related to uncertainty over course of recovery. Tonya is responsible for planning Mr. Jacobs’ nursing care from the time of her initial assessment in the morning until the end of her shift. The care that she plans will continue throughout the course of Mr. Jacobs’ hospital stay by the other nurses involved in Mr. Jacobs’ care. If Tonya plans well, the individualized interventions that she selects will prepare the patient for a smooth transition home. Collaboration with the patient is critical for a plan of care to be successful. Using input from Mr. Jacobs, Tonya identifies the goals and expected outcomes for each of his nursing diagnoses. The goals and outcomes direct Tonya in selecting appropriate therapeutic interventions. Tonya knows that Mrs. Jacobs’ must be involved in the patient’s care because of the ongoing support that she provides and because she will be a key care provider once Mr. Jacobs’ returns home. In addition, Mr. Jacobs has told Tonya that his wife is the one who keeps their family together. Consultation with other health care providers such as social work or home health ensures that the right resources are used in planning care. Careful planning involves seeing the relationships among a patient’s problems, recognizing that certain problems take precedence over others, and proceeding with a safe and efficient approach to care.

After you identify a patient’s nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems, you begin planning, the third step of the nursing process. Planning involves setting priorities, identifying patient-centered goals and expected outcomes, and prescribing individualized nursing interventions. Ultimately during implementation your interventions resolve the patient’s problems and achieve the expected goals and outcomes (see Chapter 19). Planning requires critical thinking applied through deliberate decision making and problem solving. It also involves working closely with patients, their families, and the health care team through communication and ongoing consultation. Patients benefit most when their care represents a collaborative effort from the expertise of all health care team members. A plan of care is dynamic and changes as the patient’s needs change.

Establishing Priorities

Remember that a single patient often has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems. In addition, once you enter into nursing practice, you do not care for just a single patient. Eventually you care for groups of patients. Being able to carefully and wisely set priorities for a single patient or group of patients ensures the timeliest, relevant, and appropriate care.

Priority setting is the ordering of nursing diagnoses or patient problems using determinations of urgency and/or importance to establish a preferential order for nursing actions (Hendry and Walker, 2004). In other words, as you care for a patient or a group of patients, you must deal with certain aspects of care before others. By ranking a patient’s nursing diagnoses in order of importance, you attend to each patient’s most important needs and better organize ongoing care activities. Priorities help you to anticipate and sequence nursing interventions when a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems. Together with your patients, you select mutually agreed-on priorities based on the urgency of the problems, the patient’s safety and desires, the nature of the treatment indicated, and the relationship among the diagnoses. Establishing priorities is not a matter of numbering the nursing diagnoses on the basis of severity or physiological importance. Nurses establish priorities in relation to clinical importance, but they also prioritize on the basis of time. On a given day the demands that exist within a health care setting require you to ration your time wisely.

Classify a patient’s priorities as high, intermediate, or low importance. Nursing diagnoses that, if untreated, result in harm to a patient or others (e.g., those related to airway status, circulation, safety, and pain) have the highest priorities. One way to consider diagnoses of high priority is to consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Chapter 6). For example, risk for other-directed violence, impaired gas exchange, and decreased cardiac output are examples of high-priority nursing diagnoses that drive the priorities of safety, adequate oxygenation, and adequate circulation. However, it is always important to consider each patient’s unique situation. High priorities are sometimes both physiological and psychological and may address other basic human needs. Avoid classifying only physiological nursing diagnoses as high priority. Consider Mr. Jacobs’ case. Among his nursing diagnoses, acute pain and anxiety are of the highest priority. Tonya knows that she needs to relieve Mr. Jacobs’ acute pain and lessen his anxiety so he will be responsive to discharge education and be able to participate in postoperative care activities.

Intermediate priority nursing diagnoses involve nonemergent, nonlife-threatening needs of patients. In Mr. Jacobs’ case, deficient knowledge and impaired physical mobility are both intermediate diagnoses. It is important for Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs’ to understand potential problems that develop following surgery, know how to recognize the problems, and be able to continue appropriate care at home. Focused and individualized instruction from all members of the health care team is necessary throughout a patient’s hospitalization. The diagnosis of impaired physical mobility is not life threatening and will likely resolve once Tonya and the other nurses collaborate with the surgeon to ensure effective pain control. Relief of pain will make Mr. Jacobs’ more mobile and more active in his road to recovery.

Low-priority nursing diagnoses are not always directly related to a specific illness or prognosis but affect the patient’s future well-being. Many low-priority diagnoses focus on the patient’s long-term health care needs. Tonya has not yet identified a nursing diagnosis related to Mr. Jacobs’ concern about his sexual function. At this point the patient’s anxiety over the uncertainty of the success of surgery, the risk of cancer recurrence, and his concern about his sexual function are the predominant problems. If the patient learns from the surgeon that the procedure resulted in damage to the nerves affecting his sexual performance, a diagnosis more pertinent to this health problem is appropriate.

The order of priorities changes as a patient’s condition changes, sometimes within a matter of minutes. Each time you begin a sequence of care such as at the beginning of a hospital shift or a patient’s clinic visit, it is important to reorder priorities. For example, when Tonya first met Mr. Jacobs, his acute pain was rated at a 7, and it was apparent that the administration of an analgesic was more a priority than trying to reposition or use other nonpharmacological approaches (e.g., relaxation or distraction). Later, after receiving the analgesic, Mr. Jacobs’ pain lessened to a level of 4; and Tonya was able to gather more assessment information and begin to focus on his problem of deficient knowledge. Ongoing patient assessment is critical to determine the status of your patient’s nursing diagnoses. The appropriate ordering of priorities ensures that you meet a patient’s needs in a timely and effective way.

Priority setting begins at a holistic level when you identify and prioritize a patient’s main diagnoses or problems (Hendry and Walker, 2004). However, you also need to prioritize the specific interventions or strategies that you will use to help a patient achieve desired goals and outcomes. For example, as Tonya considers the high-priority diagnosis of acute pain for Mr. Jacobs, she decides during each encounter which intervention to do first among these options: administering an analgesic, repositioning, and teaching relaxation exercises. Critical thinking helps her to prioritize. Tonya knows that a certain degree of pain relief is necessary before a patient can participate in relaxation exercises. When she is in the patient’s room, she might decide to turn and reposition Mr. Jacobs first and then prepare the analgesic. However, if Mr. Jacobs expresses that pain is a high level and is too uncomfortable to turn, Tonya chooses obtaining and administering the analgesic as her first priority. Later, with Mr. Jacobs’ pain more under control, she considers whether relaxation is appropriate.

Involve patients in priority setting whenever possible. Patient-centered care requires you to know a patient’s preferences, values, and expressed needs. Tonya must learn what Mr. Jacobs expects with regard to pain control to have a relevant plan of care in place. In some situations a patient assigns priorities different from those you select. Resolve any conflicting values concerning health care needs and treatments with open communication, informing the patient of all options and consequences. Consulting with and knowing the patient’s concerns do not relieve you of the responsibility to act in a patient’s best interests. Always assign priorities on the basis of good nursing judgment.

Ethical care is a part of priority setting. When ethical issues make priorities less clear, it is important to have open dialogue with the patient, the family, and other health care providers (Holmstrom and Hoglund, 2007). For example, when you care for a patient nearing death or one newly diagnosed with a chronic long-term disabling disease, you need to be able to discuss the situation fully with the patient, know his or her expectations, know your own professional responsibility in protecting the patient from harm, know the physician’s therapeutic or palliative goals, and then form a plan of care. Chapter 22 outlines strategies for choosing a course of action when facing an ethical dilemma.

Priorities in Practice

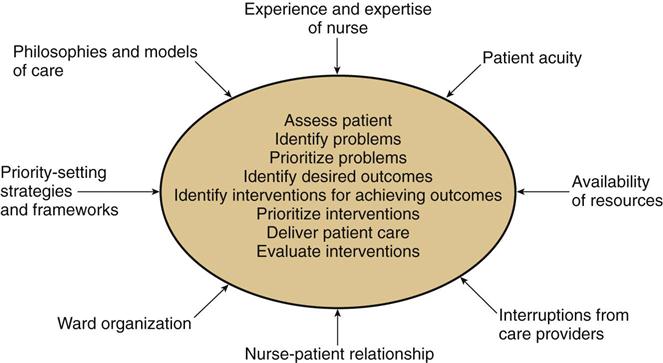

Hendry and Walker (2004) address an important issue regarding priority setting (Fig. 18-1). Many factors within the health care environment affect your ability to set priorities. For example, in the hospital setting the model for delivering care (see Chapter 21), the organization of a nursing unit, staffing levels, and interruptions from other care providers affect the minute-by-minute determination of patient care priorities. Available resources (e.g., nurse specialists, laboratory technicians, and dietitians), policies and procedures, and supply access affect priorities as well. Finally, patients’ conditions are always changing; thus priority setting is always changing.

The same factors that influence your minute-by-minute ability to prioritize nursing actions affect the ability to prioritize nursing diagnoses for groups of patients. The nature of nursing work challenges your ability to cognitively attend to a given patient’s priorities when you care for more than one patient. The nursing care process is nonlinear (Potter et al., 2005). Often you complete an assessment and identify nursing diagnoses for one patient, leave the room to perform an intervention for a second patient, and move on to consult on a third patient. Nurses exercise “cognitive shifts” (i.e., shifts in attention from one patient to another during the conduct of the nursing process). This shifting of attention occurs in response to changing patient needs, new procedures being ordered, or environmental processes interacting (Potter et al., 2005). Because of these cognitive shifts, it becomes important to stay organized and know your patients’ priorities. Always work from your plan of care and use your patients’ priorities to organize the order for delivering interventions and organizing documentation of care.

Critical Thinking in Setting Goals and Expected Outcomes

Once you identify nursing diagnoses for a patient, ask yourself, “What is the best approach to address and resolve each problem? What do I plan to achieve?” Goals and expected outcomes are specific statements of patient behavior or physiological responses that you set to resolve a nursing diagnosis or collaborative problem. For example, Tonya chooses to administer ordered analgesics for Mr. Jacobs’ acute pain and provide nursing measures that promote relaxation and minimize any other sources of discomfort. She hopes to achieve pain relief (goal). The specific patient behaviors or physiological responses (expected outcomes) include Mr. Jacobs’ reporting pain at a level below 4, showing more freedom in movement and less grimacing, and being able to participate in education sessions.

During planning you select goals and outcomes for each nursing diagnosis to provide a clear focus for the type of interventions needed to care for your patient and to then evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions. A goal is a broad statement that describes a desired change in a patient’s condition or behavior. Mr. Jacobs has the diagnosis of deficient knowledge regarding his postoperative recovery. A goal of care for this diagnosis includes, “Patient expresses understanding of postoperative risks.” The goal requires making Mr. Jacobs aware of the risks associated with his type of surgery. It gives Tonya a clear focus on the topics to include in her instruction. An expected outcome is a measurable criterion to evaluate goal achievement. Once an outcome is met, you then know that a goal has been at least partially achieved. Sometimes several expected outcomes must be met for a single goal. Measurable outcomes for the goal of “understanding postoperative risks” include: “Patient identifies signs and symptoms of wound infection,” and “Patient explains signs of urinary obstruction,” both risks from a prostatectomy. After Tonya instructs Mr. Jacobs, she determines if he can identify signs and symptoms of wound infection; if so, the goal is partially met. If the patient can also explain signs of urinary obstruction, the goal is fully met.

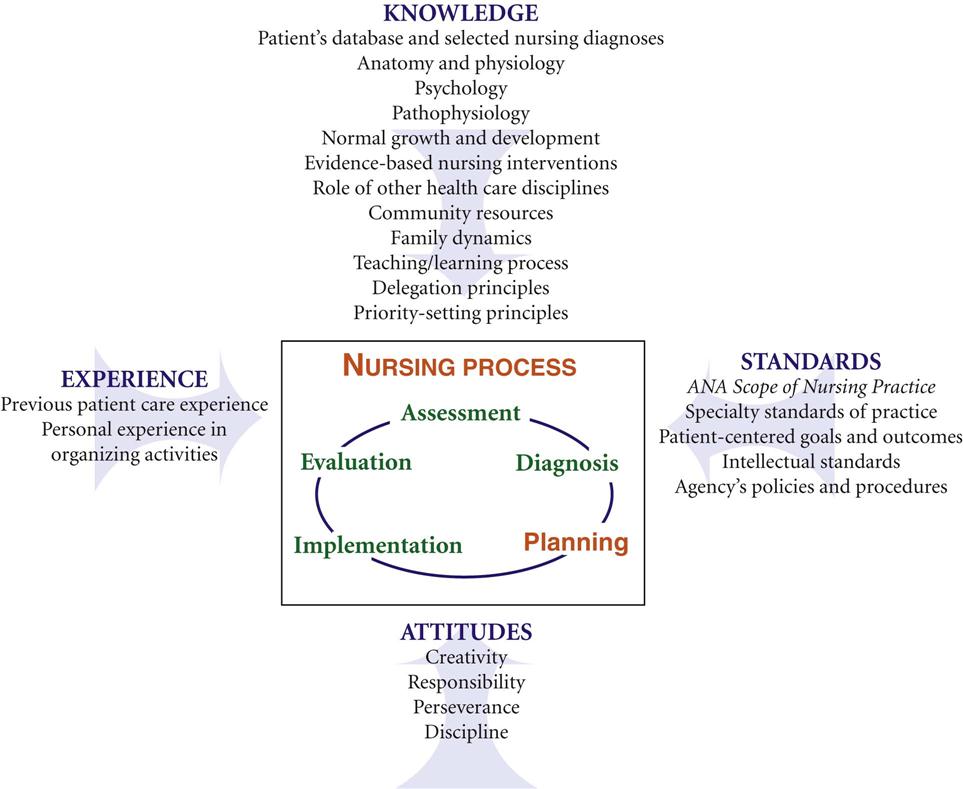

Planning nursing care requires critical thinking (Fig. 18-2). Critically evaluate the identified nursing diagnoses, the urgency or priority of the problems, and the resources of the patient and the health care delivery system. You apply knowledge from the medical, sociobehavioral, and nursing sciences to plan patient care. The selection of goals, expected outcomes, and interventions requires consideration of your previous experience with similar patient problems and any established standards for clinical problem management. The goals and outcomes need to meet established intellectual standards by being relevant to patient needs, specific, singular, observable, measurable, and time limited. You also use critical thinking attitudes in selecting interventions with the greatest likelihood of success.

Goals of Care

A patient-centered goal reflects a patient’s highest possible level of wellness and independence in function. It is realistic and based on patient needs and resources. For example, consider the diagnoses of acute pain versus chronic pain. A patient such as Mr. Jacobs with acute pain can realistically expect pain relief. In contrast, a patient with terminal bone cancer in chronic pain can only expect an acceptable level of pain control. A patient goal represents a predicted resolution of a diagnosis or problem, evidence of progress toward resolution, progress toward improved health status, or continued maintenance of good health or function (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009).

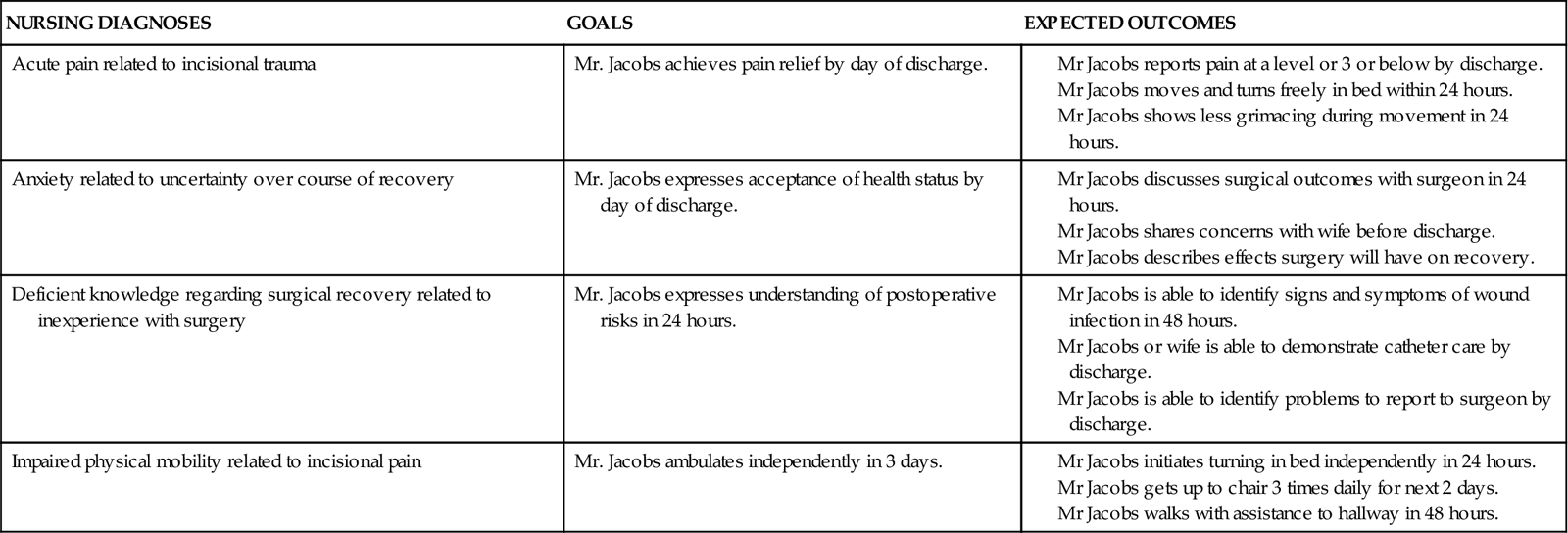

Each goal is time limited so the health care team has a common time frame for problem resolution. For example, the goal of “patient will achieve pain relief” for Mr. Jacobs is complete by adding the time frame “by day of discharge.” With this goal in place, all efforts by the health care team are aimed at managing the patient’s pain. At the time of discharge evaluation of expected outcomes (e.g., pain-rating score, signs of grimacing, level of movement) show if the goal was met. The time frame depends on the nature of the problem, etiology, overall condition of the patient, and treatment setting. A short-term goal is an objective behavior or response that you expect a patient to achieve in a short time, usually less than a week. In an acute care setting you often set goals for over a course of just a few hours. A long-term goal is an objective behavior or response that you expect a patient to achieve over a longer period, usually over several days, weeks, or months (e.g., “Patient will be tobacco free within 60 days”). Table 18-1 shows the progression from nursing diagnoses to goals and expected outcomes and the relationship to nursing interventions.

TABLE 18-1

Examples of Goal Setting with Expected Outcomes for Mr. Jacobs

Role of the Patient in Goal Setting

Always partner with patients when setting their individualized goals. Mutual goal setting includes the patient and family (when appropriate) in prioritizing the goals of care and developing a plan of action. For patients to participate in goal setting, they need to be alert and have some degree of independence in completing activities of daily living, problem solving, and decision making. Unless goals are mutually set and there is a clear plan of action, patients fail to fully participate in the plan of care. Patients need to understand and see the value of nursing therapies, even though they are often totally dependent on you as the nurse. When setting goals, act as an advocate or support for the patient to select nursing interventions that promote his or her return to health or prevent further deterioration when possible.

Tonya has a discussion with Mr. Jacobs and his wife together about setting the plan for the diagnosis of deficient knowledge. Tonya explains the topics that they need to discuss so the couple understands Mr. Jacobs’ postoperative risks. They plan the instruction the next day just before lunch when Mrs. Jacobs’ visits. Mr. Jacobs asks to have the instruction also include information on how the surgery can affect his sexual function. Tonya agrees and plans to clarify with the surgeon so the information is accurate and realistic. The surgeon has told Mr. Jacobs that there is a risk, but it is too early to know the extent of any possible nerve damage.

Expected Outcomes

An expected outcome is a specific measurable change in a patient’s status that you expect to occur in response to nursing care. Outcomes as a result of Mr. Jacobs’ postoperative instruction include his ability to describe signs of a surgical wound infection and identify when to call his surgeon with problems. Expected outcomes direct nursing care because they are the desired physiological, psychological, social, developmental, or spiritual responses that indicate resolution of a patient’s health problems. A patient’s willingness and capability to reach an expected outcome improves his or her likelihood of achieving it. Taken from both short- and long-term goals, outcomes determine when a specific patient-centered goal has been met.

Usually you develop several expected outcomes for each nursing diagnosis and goal because sometimes one nursing action is not enough to resolve a patient problem. In addition, a list of the step-by-step expected outcomes gives you practical guidance in planning interventions. Always write expected outcomes sequentially, with time frames (see Table 18-1). Time frames give you progressive steps in which to move a patient toward recovery and offer an order for nursing interventions. They also set limits for problem resolution.

Nursing Outcomes Classification

Much attention in the current health care environment is focused on measuring outcomes to gauge the quality of health care. If a chosen intervention repeatedly results in desired outcomes that benefit patients, it needs to become part of a standardized approach to a patient problem. For example, if the use of a chlorhexidine mouthwash (intervention) repeatedly results in a lower incidence of aspiration pneumonia (outcome) in critically ill patients, use of the mouthwash needs to become part of standard mouth care in critical care units.

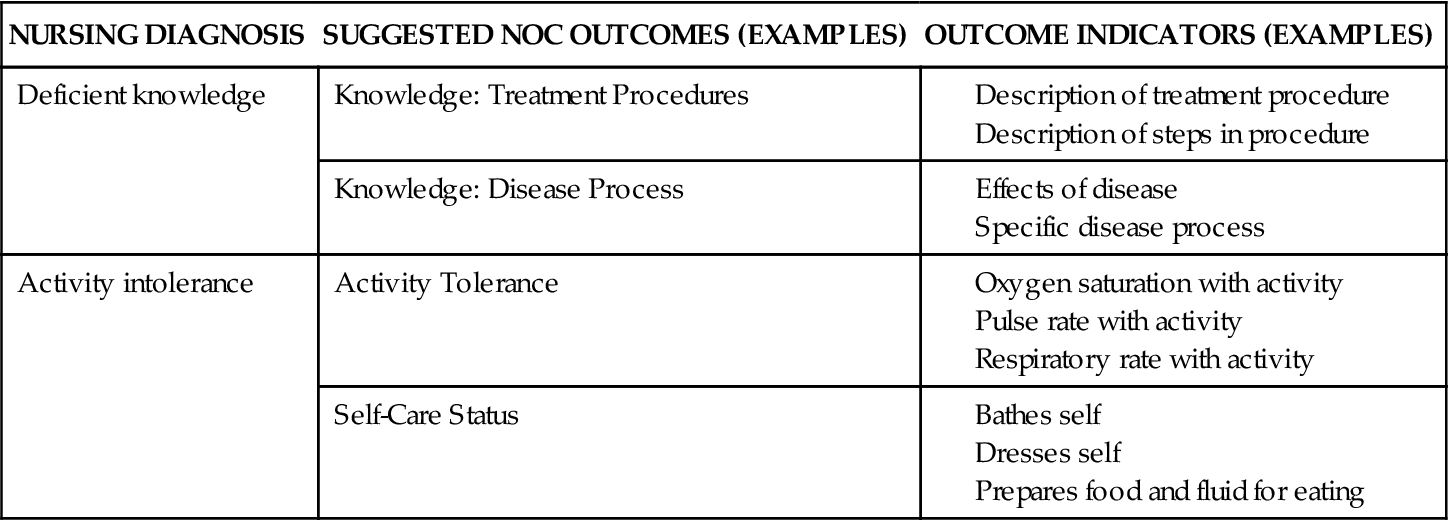

Nursing plays an important role in monitoring and managing patient conditions and diagnosing problems that are amenable to nursing intervention. The clinical reasoning and decision making of nurses is a key part of quality health care (Moorhead et al., 2008). Thus it becomes important to identify and measure patient outcomes that are influenced by nursing care. A nursing-sensitive patient outcome is a measurable patient, family or community state, behavior, or perception largely influenced by and sensitive to nursing interventions (Moorhead et al., 2008). For the nursing profession to become a full participant in clinical evaluation research, policy development, and interdisciplinary work, nurses need to identify and measure patient outcomes influenced by nursing interventions. The Iowa Intervention Project has done just that. It published the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) and linked the outcomes to NANDA International nursing diagnoses (Moorhead et al., 2008). For each NANDA International nursing diagnosis there are multiple NOC suggested outcomes. These outcomes have labels for describing the focus of nursing care and include indicators to use in evaluating the success with nursing interventions (Table 18-2). NOC contains outcomes for individuals, family caregivers, the family, and the community in all health care settings. Efforts to measure outcomes and capture the changes in the status of patients over time allow nurses to improve patient care quality and add to nursing knowledge (Moorhead et al., 2008). The use of a common set of outcomes allows nurses to study the effects of nursing interventions over time and across settings. The fourth edition of NOC standardizes the way to measure patient outcomes. It is an excellent resource for you to develop care plans and concept maps. NOC outcomes provide a common nursing language for continuity of care and measurement of the success of nursing interventions.

TABLE 18-2

Examples of NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses and Suggested NOC Linkages

Guidelines for Writing Goals and Expected Outcomes

There are seven guidelines for writing goals and expected outcomes.

Patient-Centered

Outcomes and goals reflect patient behaviors and responses expected as a result of nursing interventions. Write a goal or outcome to reflect a patient’s specific behavior, not to reflect your goals or interventions.

Singular Goal or Outcome

You want to be precise when you evaluate a patient’s response to a nursing action. Each goal and outcome should address only one behavior or response. If an outcome reads, “Patient’s lungs will be clear to auscultation, and respiratory rate will be 20 breaths per minute by 8/22,” your measurement of outcomes will be complicated. When you evaluate that the lungs are clear but the respiratory rate is 28 breaths per minute, you do not know if the patient achieved the expected outcome. By splitting the statement into two parts, “Lungs will be clear to auscultation by 8/22,” and “Respiratory rate will be 20 breaths per minute by 8/22,” you are able to determine if and when the patient achieves each outcome. Singularity allows you to decide if there is a need to modify the plan of care.

A goal also contains only one behavior or response. The example, “Patient will administer a self-injection and demonstrate infection control measures,” is incorrect because the statement includes two different behaviors, administer and demonstrate. Instead word the goal as follows, “Patient will administer a self-injection by discharge.” The specific criteria you use to measure success of the goal are the singular expected outcomes. For example, “Patient will prepare medication dose correctly,” and “Patient uses medical asepsis when preparing injection site.”

Observable

You need to be able to observe if change takes place in a patient’s status. Observable changes occur in physiological findings and in the patient’s knowledge, perceptions, and behavior. You observe outcomes by directly asking patients about their condition or using assessment skills. For example, you observe the goal, “Patient will be able to self-administer insulin,” through the outcome of watching, “Patient prepares insulin dosage correctly by 8/30.” For the outcome, “Lungs will be clear on auscultation by 8/31,” you auscultate the lungs following any therapy. The outcome statement, “Patient will appear less anxious,” is not correct because there is no specific behavior observable for “will appear.” A more correct outcome is, “Patient will show better eye contact during conversations.”

Measurable

You learn to write goals and expected outcomes that set standards against which to measure the patient’s response to nursing care. Examples such as, “Body temperature will remain 98.6° F,” and, “Apical pulse will remain between 60 and 100 beats per minute,” allow you to objectively measure changes in the patient’s status. Do not use vague qualifiers such as “normal,” “acceptable,” or “stable” in an expected outcome statement. Vague terms result in guesswork in determining a patient’s response to care. Terms describing quality, quantity, frequency, length, or weight allow you to evaluate outcomes precisely.

Time-Limited

The time frame for each goal and expected outcome indicates when you expect the response to occur. It is very important to collaborate with patients to set realistic and reasonable time frames. Time frames help you and the patient to determine if the patient is making progress at a reasonable rate. If not, you must revise the plan of care. Time frames also promote accountability in delivering and managing nursing care.

Mutual Factors

Mutually set goals and expected outcomes ensure that the patient and nurse agree on the direction and time limits of care. Mutual goal setting increases the patient’s motivation and cooperation. As a patient advocate, apply standards of practice, evidence-based knowledge, safety principles, and basic human needs when assisting patients with setting goals. Your knowledge background helps you select goals and outcomes that should be met on the basis of typical responses to clinical interventions. Yet you must consider patients’ desires to recover and their physical and psychological condition to set goals and outcomes to which they can agree.

Realistic

Set goals and expected outcomes that a patient is able to reach based on your assessment. This is a challenge when the time allotted for care is limited. But it also means that you must communicate these goals and outcomes to caregivers in other settings who will assume responsibility for patient care (e.g., home health, rehabilitation). Realistic goals provide patients a sense of hope that increases motivation and cooperation. To establish realistic goals, assess the resources of the patient, health care facility, and family. Be aware of the patient’s physiological, emotional, cognitive, and sociocultural potential and the economic cost and resources available to reach expected outcomes in a timely manner.

Critical Thinking in Planning Nursing Care

Part of the planning process is to select nursing interventions for meeting the patient’s goals and outcomes. Once nursing diagnoses have been identified and goals and outcomes are selected, you choose interventions individualized for the patient’s situation. Nursing interventions are treatments or actions based on clinical judgment and knowledge that nurses perform to meet patient outcomes (Bulechek et al., 2008). During planning you select interventions designed to help a patient move from the present level of health to the level described in the goal and measured by the expected outcomes. The actual implementation of these interventions occurs during the implementation phase of the nursing process (see Chapter 19).

Choosing suitable nursing interventions involves critical thinking and your ability to be competent in three areas: (1) knowing the scientific rationale for the intervention, (2) possessing the necessary psychomotor and interpersonal skills, and (3) being able to function within a particular setting to use the available health care resources effectively (Bulechek et al., 2008).

Types of Interventions

There are three categories of nursing interventions: nurse-initiated, physician-initiated, and collaborative interventions. Some patients require all three categories, whereas other patients need only nurse- and physician-initiated interventions.

Nurse-initiated interventions are the independent nursing interventions, or actions that a nurse initiates. These do not require an order from another health care professional. As a nurse you act independently on a patient’s behalf. Nurse-initiated interventions are autonomous actions based on scientific rationale. Examples include elevating an edematous extremity, instructing patients in side effects of medications, or repositioning a patient to achieve pain relief. Such interventions benefit a patient in a predicted way related to nursing diagnoses and patient goals (Bulechek et al., 2008). Nurse-initiated interventions require no supervision or direction from others. Each state within the United States has Nurse Practice Acts that define the legal scope of nursing practice (see Chapter 23). According to the Nurse Practice Acts in a majority of states, independent nursing interventions pertain to activities of daily living, health education and promotion, and counseling. For Mr. Jacobs Tonya selects anxiety-reduction interventions such as using a calm and reassuring approach, listening attentively, and providing factual information.

Physician-initiated interventions are dependent nursing interventions, or actions that require an order from a physician or another health care professional. The interventions are based on the physician’s or health care provider’s response to treat or manage a medical diagnosis. Advanced practice nurses who work under collaborative agreements with physicians or who are licensed independently by state practice acts are also able to write dependent interventions. As a nurse you intervene by carrying out the provider’s written and/or verbal orders. Administering a medication, implementing an invasive procedure (e.g., inserting a Foley catheter, starting an intravenous [IV] infusion), changing a dressing, and preparing a patient for diagnostic tests are examples of physician-initiated interventions.

Each physician-initiated intervention requires specific nursing responsibilities and technical nursing knowledge. You are often the one performing the intervention, and you must know the types of observations and precautions to take for the intervention to be delivered safely and correctly. For example, when administering a medication you are responsible for not only giving the medicine correctly, but also knowing the classification of the drug, its physiological action, normal dosage, side effects, and nursing interventions related to its action or side effects (see Chapter 31). You are responsible for knowing when an invasive procedure is necessary, the clinical skills necessary to complete it, and its expected outcome and possible side effects. You are also responsible for adequate preparation of the patient and proper communication of the results. You perform dependent nursing interventions, like all nursing actions, with appropriate knowledge, clinical reasoning, and good clinical judgment.

Collaborative interventions, or interdependent interventions, are therapies that require the combined knowledge, skill, and expertise of multiple health care professionals. Typically when you plan care for a patient, you review the necessary interventions and determine if the collaboration of other health care disciplines is necessary. A patient care conference with an interdisciplinary health care team results in selection of interdependent interventions.

In the case study involving Mr. Jacobs, Tonya plans independent interventions to help calm Mr. Jacobs’ anxiety and begin teaching him about postoperative care activities. Among the dependent interventions Tonya plans to implement are the administration of an analgesic and ordered wound care. Tonya’s collaborative intervention involves consulting with the unit discharge coordinator, who will help Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs plan for their return home and consult with the home health department to ensure that the Jacobs have home health visits.

When preparing for physician-initiated or collaborative interventions, do not automatically implement the therapy but determine whether it is appropriate for the patient. Every nurse faces an inappropriate or incorrect order at some time. The nurse with a strong knowledge base recognizes the error and seeks to correct it. The ability to recognize incorrect therapies is particularly important when administering medications or implementing procedures. Errors occur in writing orders or transcribing them to a documentation form or computer screen. Clarifying an order is competent nursing practice, and it protects the patient and members of the health care team. When you carry out an incorrect or inappropriate intervention, it is as much your error as the person who wrote or transcribed the original order. You are legally responsible for any complications resulting from the error (see Chapter 23).

Selection of Interventions

During planning do not select interventions randomly. For example, patients with the diagnosis of anxiety do not always need care in the same way with the same interventions. You treat anxiety related to the uncertainty of surgical recovery very differently than anxiety related to a threat to loss of family role function. When choosing interventions, consider six important factors: (1) characteristics of the nursing diagnosis, (2) goals and expected outcomes, (3) evidence base (e.g., research or proven practice guidelines) for the interventions, (4) feasibility of the intervention, (5) acceptability to the patient, and (6) your own competency (Bulechek et al., 2008) (Box 18-1). When considering a plan of care, review resources such as the nursing literature, standard protocols or guidelines, the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), critical pathways, policy or procedure manuals, or textbooks. Collaboration with other health professionals is also useful. As you select interventions, review your patient’s needs, priorities, and previous experiences to select the interventions that have the best potential for achieving the expected outcomes.