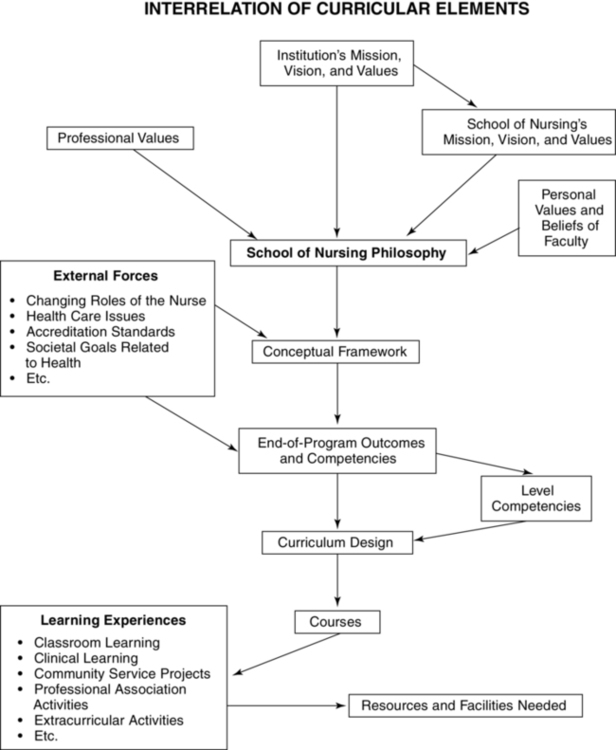

This chapter will explore the significance of reflecting on, articulating, and being guided by a philosophy; examine the essential components of a philosophy for a school of nursing; and point out how philosophical statements guide the design and implementation of the curriculum, as well as the evaluation of its effectiveness. The role of faculty, administrators, and students in crafting and “living” the philosophy will be discussed, and the issues and debates surrounding the “doing of philosophy” (Greene, 1973) will be examined. Finally, suggestions will be offered regarding how faculty might go about writing or revising the school’s philosophy. The educational philosopher Maxine Greene (1973) challenged educators to “do philosophy.” By this she meant that we need to take the risk of thinking about what we do when we teach and what we mean when we talk of enabling others to learn. It also means we need to become progressively more conscious of the choices and commitments we make in our professional lives. Greene also challenged educators to look at our presuppositions, to examine critically the principles underlying what we think and what we say as educators, and to confront the individuals within us. She acknowledged that we often have to ask and answer painful questions when we “do philosophy.” In his seminal book, The Courage to Teach, Parker Palmer (2007) asserted that “though the academy claims to value multiple modes of knowing, it honors only one—an ‘objective’ way of knowing that takes us into the ‘real’ world by taking us ‘out of ourselves’” (p. 18). He encouraged educators to challenge this culture by bringing a more human, personal perspective to the teaching–learning experience. Like Greene, Palmer suggested that, in order to do this, educators must look inside so that we can understand that “we teach who we are” (p. xi) and so that we can appreciate that such insight is critical for “authentic teaching, learning, and living” (p. ix). A philosophy is essentially a narrative statement of values or beliefs. It reflects broad principles or fundamental “isms” that guide actions and decision making, and it expresses the assumptions we make about people, situations, or goals. As noted by Bevis (1989, p. 35), the philosophy “provides the value system for ordering priorities and selecting from among various data.” We also must reflect on the mission, vision, and values of our parent institution and of our school itself, as well as on the values of our profession. Figure 7-1 illustrates how a school’s statement of philosophy is related to but different than these other sources. A mission statement describes unique purposes for which an institution or nursing unit exists: to improve the health of the surrounding community, to advance scientific understanding or contribute to the development of nursing science, to prepare responsible citizens, or to graduate individuals who will influence public policy to ensure access to quality health care for all. A vision is an expression of what an institution or nursing unit wants to be: the institution of choice for highly qualified students wishing to make a positive difference in our world; the leader in innovative integration of technology in the preparation of nurses; or a center of synergy for teaching, research, professional practice, and public service. Institutions and schools of nursing often also articulate a set of values that guide their operation: honesty and transparency, serving the public good, excellence, innovation, or constantly being open to change and transformation. As noted earlier, “doing philosophy” must move from individual work to group work when engaged in curriculum development, implementation, and evaluation. Faculty need to reflect on their own individual beliefs and values, share them with colleagues, affirm points of agreement, and discuss points of disagreement. Table 7-1 summarizes many of the philosophical perspectives expressed through the years, and faculty are encouraged to explore the meaning and implications of each as they engage in developing, reviewing, or refining the philosophical statement that guides their work. A discussion of three basic educational ideologies is presented here to point out how differences might arise if each person on a faculty were to approach education from her or his own belief system only. Table 7-1 Summary of Philosophical Perspectives Adapted from Csokasy, J. (2009). Philosophical foundations of the curriculum. In D. M. Billings & J. A. Halstead, Teaching in nursing: A guide for faculty (pp. 105–118). St. Louis, MO: Saunders. One basic educational ideology is that of romanticism (Jarvis, 1995). This perspective, which emerged in the 1960s, is highly learner-centered and asserts that what comes from within the learner is most important. Within this ideological perspective, one would construct an educational environment that is permissive and freeing; promotes creativity and discovery; allows each student’s inner abilities to unfold and grow; and stresses the unique, the novel, and the personal. Bradshaw (1998, p. 104) asserted that “this ‘romantic’ educational philosophy underpins current nurse education”; however, those who acknowledge our current “content-laden curricula” in nursing (Diekelmann, 2002; Diekelmann & Smythe, 2004; Giddens & Brady, 2007; Tanner, 2010) would disagree and posit that while a “romantic” philosophy is embraced as an ideal, it is not always evident in our day-to-day practices. A second educational ideology, that of cultural transmission (Bernstein, 1975), is more society- or culture-centered. Here the emphasis is on transmitting bodies of information, rules, values, and the culturally given (i.e., the beliefs and practices that are central to our educational environments and our society in general). One would expect an educational environment that is framed within a cultural transmission perspective to be structured, rigid, and controlled, with an emphasis on the common and the already-established. The third major educational ideology has been called progressivism (Dewey, 1944; Kohlberg & Mayer, 1972), where the focus is oriented toward the future and the goal of education is to nourish the learner’s natural interaction with the world. Here the educational environment would be designed to present resolvable but genuine problems or conflicts that “force” learners to think so that they can be effective later in life. The total development of learners—not merely their cognitive or intellectual abilities—is emphasized and enhanced. Increasingly, education experts agree that development must be an overarching paradigm of education, that students must be central to the educational enterprise, and that education must be designed to empower learners and help them fulfill their potentials. Beliefs and values such as these surely would influence expectations faculty express regarding students’ and their own performance, the relationships between students and teachers, how the curriculum is designed and implemented (see Figure 7-1), and the kind of “evidence” that is gathered to determine whether the curriculum has been successful and effective. There is no doubt that a statement of philosophy for a school of nursing must address beliefs and values about education, teaching, and learning. However, it also must address other concepts that are critical to the practice of nursing, namely human beings, society and the environment, health, and the roles of nurses themselves. These major concepts have been referred to as the metaparadigm of nursing, a concept first introduced by Fawcett in 1984. • Human beings are unique, complex, holistic individuals. • Human beings have the inherent capacity for rational thinking, self-actualization, and growth throughout the life cycle. • Human beings engage in deliberate action to achieve goals. • Human beings want and have the right to be involved in making decisions that affect their lives. • All human beings have strengths as well as weaknesses, and they often need support and guidance to capitalize on those strengths or to overcome or manage those weaknesses or limitations.

Philosophical foundations of the curriculum

What is philosophy?

Philosophical statements

Philosophy as it relates to nursing education

Philosophical Perspective

Brief Description

Behaviorism

Education focuses on developing mental discipline, particularly through memorization, drill, and recitation. Since learning is systematic, sequential building on previous learning is important.

Essentialism

Since knowledge is key, the goal of education is to transmit and uphold the cultural heritage of the past.

Existentialism

The function of education is to help individuals explore reasons for existence. Personal choice and commitment are crucial.

Hermeneutics

Since individuals are self-interpreting beings, uniquely defined by personal beliefs, concerns, and experiences of life, education must attend to the meaning of experiences for learners.

Humanism

Education must provide for learner autonomy and respect their dignity. It also must help individuals achieve self-actualization by developing their full potential.

Idealism

Individuals desire to live in a perfect world of high ideals, beauty, and art, and they search for ultimate truth. Education assists in this search.

Postmodernism

Education challenges convention, values a high tolerance for ambiguity, emphasizes diversity of culture and thought, and encourages innovation and change.

Pragmatism

Truth is relative to an individual’s experience; education, therefore, must provide for “real-world” experiences.

Progressivism

The role of learners is to make choices about what is important, and the role of teachers is to facilitate their learning.

Realism

Education is designed to help learners understand the natural laws that regulate all of nature.

Reconstructionism

Education embraces the social ideal of a democratic life, and the school is viewed as the major vehicle for social change.

Central concepts in a school of nursing’s philosophy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Philosophical foundations of the curriculum

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access