Personal knowledge development

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

Self is a dynamic concept, ever deepening as we expand and broaden our relationships with others. The Self is created in relation to others.

Beverly Hall and Janet Allan (1994, p. 112)

The opening quote for this chapter suggests that people know who they are through their relationships with others and that who a person is changes over time. In this context, the idea of relationships does not imply only close or intimate relationships, such as might be the case when someone is in a relationship with a significant other. Rather, relationships include contacts and interactions with the people that you relate to from day to day. These relationships can be intimate to varying degrees, casual, and even so subtle as to go unnoticed. In addition, in the context of personal knowing for this text, you can also have a relationship with your Self that reflects who you really are as compared with the Self that you project or want others to see.

In a sense, all knowing is personal knowing, because people can only know their own understandings, mental images, perceptions, experiences, memories, and thoughts (Bonis, 2009). However, for the purposes of this text and for the construct of patterns of knowing in nursing, we use the concept of personal knowing to refer to a process of Self-knowing that is shaped by your relationships with others and that also shapes your relationships when caring for others. As such, personal knowing cultivates your wholeness and the wholeness of others.

Consider the example of a young woman named Alia who might be characterized as a jet-setter. Alia has much wealth at her disposal and has not had to work or become educated to maintain her standard of living. She is hospitalized because she was driving while impaired and sustained multiple injuries when her sports car ran off a cliff.

The nurse assigned to care for Alia has come to know her Self as a hardworking person who is responsible. The nurse knows this, in large part, because her parents and teachers have reflected to her and her brothers the importance of making something of themselves. Her parents taught their children to work hard, to get a good education, and to contribute meaningfully to society. The nurse did this, although it was not easy. Her parents also reflected to the children that those who have wealth and do nothing productive are undeserving if not contemptible. As a result, the nurse has a deeply held value that worthiness is a byproduct of being responsible and socially productive. At the same time, this nurse was also taught in her nursing program that each person deserves to be respected and cared for as an individual, despite who they may be, and that each person is inherently valuable. Thus, if the nurse was aware that her nursing care for Alia was lacking in any way, she would be appalled.

As the nurse cares for Alia, it is inevitable that who the nurse is as a person—her core Self—will affect her nursing care. Without fully realizing it, she might withhold comfort measures a bit longer than she otherwise would, or she might not be helpful when a special menu request is made. She might not make an effort to get to know anything about Alia as a human being but rather focus on her care as just another situation to tolerate and get through.

In this example, the Self of the nurse and the nurse’s care would benefit by a focus on personal knowing. Personal knowing requires that you be in touch with who you are and understand that who you are as a person affects your behavior, attitudes, and values both positively and negatively. Through personal knowing, you live your life with deliberate intent; your actions come to be in harmony with your deepest intentions. In short, personal knowing is the dynamic process of becoming a whole, aware Self and of knowing the other as being valued and whole. It brings you to a place of knowing what you do and doing what you know.

Personal knowing is the basis for the expression of an authentic or genuine Self; it is also essential for a healing relationship, and it is fundamental to the essence of what it means to be human (Green, 2009). Returning to our example, assume that the nurse was able to tolerate Alia despite her feelings toward her and thus was able to provide acceptable care. Tolerance alone does not engender the growth of personal knowing. However, if the nurse began to reflect on how she truly felt about Alia, she could then begin to recognize the basis of her feelings and how those feelings affect her nursing care. As the nurse reflects on her background and how it affects who she is, she can make a conscious choice about the person that she wants to be as a nurse. Through this process, the nurse becomes more genuine and authentic. Her actions grow to be more in harmony with what she would choose them to be: compassionate and caring toward Alia, just as they would be toward any other person.

Personal knowing in nursing

Personal knowing as knowledge of the Self is perhaps the most difficult pattern to understand, because the nature of the Self and knowing the Self are elusive concepts. The ideal of personal knowing is to become a more whole and authentic Self. To know who you are, you need to embrace, internalize, and reflect on the responses that you get from others as a clue to the Self that you are. As you more fully understand your Self, you can begin to bring your actions into harmony with the kind of person that you want to be.

Personal knowing is expressed as the Self: the person you are. In other words, you are known to others because of who you are. Initially, people recognize you because you have a certain appearance; your face and other features of your physical Self are recognizable. People begin to know you by name. As they come to really know you as a person, people recognize not only your physical appearance but qualities of your Self that are expressed through your actions and the choices that you make from day to day. You might be known as someone who has a great sense of humor, who likes beans but not carrots, who loves to dance, or who is afraid of heights. All of these things and many more constitute the “you” that others come to know and make you distinctly recognizable as you and not someone else. Others experience and know you as unique by virtue of your deeply personal qualities that are conveyed through being in the world within the context of the culture.

You know your Self as the person you are in part because of how others perceive you. You may not appreciate how great your sense of humor is, for example, unless other people come to recognize this in you and give you feedback about it. You might not be aware that your food likes and dislikes are so obvious to others, and, once you sense how they react to your being a certain kind of eater, you might decide to learn to change how you approach your food choices. At a deeper level, as you reflect not only on the reactions of others but also on how it feels to you to be you, you begin to make deliberate choices about the kind of person you really want to be in the world. This process is what we refer to as personal knowing. It is an ongoing process that leads to change and growth toward wholeness, authenticity, mind-body-spirit congruence, and genuineness.

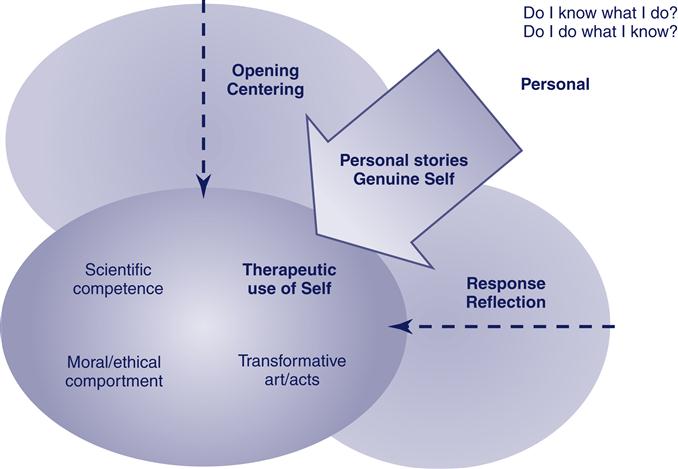

The following sections of this chapter detail the dimensions of personal knowing and provide examples of concepts related to personal knowing. Figure 5-1 provides an overview of the personal knowing pattern of our model for knowledge development in nursing. As the figure illustrates, nurses bring to their practice the Self that they are. As they care for others and reflect on their caring practices, knowing arises as they ask critical questions: “Do I know what I do?” and “ Do I do what I know?” The creative processes of opening and centering flow from these questions, and these creative processes foster the development of formal expressions of personal knowing.

One formal expression of personal knowing is the genuine Self. The genuine Self conveys directly, without words, who one is. Personal or autobiographical stories are also formal expressions of personal knowing, but they are less direct than the actual Self (i.e., the person in the world). Personal stories are limited in their capacity to convey the fullness of the person, but they provide a means of communication with a wide audience and illuminate various paths to the creation of a more genuine Self. The processes of response and reflection are the authentication processes within the personal knowing pattern. Response and reflection in relation to personal knowledge expressions are necessary for us to know who we are as individuals, and they are the basis for continued growth. According to our model, nurses who practice using personal knowledge that has been strengthened through the authentication processes of reflection and response will increasingly improve with regard to the ability to use the Self therapeutically. As seen in Figure 5-1, the integrated expression of personal knowing in practice is the therapeutic use of the Self. This chapter opens with an exploration of the conceptual meanings of personal knowing in nursing and then details the dimensions of personal knowing as identified in Figure 5-1.

Conceptual meanings of personal knowing

Carper’s (1978) early description of personal knowing points directly to transcendent interpersonal encounters as central defining qualities of personal knowing:

One does not know about the self; one simply strives to know the self. This knowing is a process of symbolically standing in relation to another human being and confronting that human being as a person. This “ I-Thou” encounter is unmediated by conceptual categories or particulars abstracted from complex organic wholes. The relation is one of reciprocity, a state of being that cannot be described or even experienced—it only can be actualized (p. 18).

For Carper, personal knowing is connected to an “I-Thou” encounter that actualizes the Self in a way that is instantaneous and transcendent. If you have ever had an experience—most likely a powerful and memorable one—during which you “just knew” or “understood” something about another and your Self without contemplating or thinking about the person, then you most likely have experienced what Carper conceptualized personal knowing to be. This sort of personal knowing just happens in a compelling human-to-human moment, and it is both transcendent and immediate. For Carper, personal knowing actualizes the wholeness and integrity in each encounter and immediately knows and affirms the Self of the person.

Examples are difficult because personal knowing as Carper conceptualized it is not explained or recounted, it is only experienced. However, an encounter that a young nurse described comes to mind as an example. A young man she was caring for was slowly dying from an abdominal gunshot wound that he suffered while committing a petty crime. One day, during the course of care, this young man motioned for the nurse to come to his bedside. As she approached, he held out his arms, pulled her in close to his face, and whispered, “You are the best nurse I ever had.” In that moment, this young man was fully known not as a criminal or a dying man but simply as a person. It was an unmediated and unexpected knowing of Self and other that just was. To this day, the recollection of this moment that occurred more than 40 years ago is still vivid and powerful for this nurse. We believe that this type of in-the-moment knowing of another is the “I-Thou” experience that Carper associated with personal knowing.

Personal knowing as spiritual in nature

Personal knowing has been linked with spirit and to what is sometimes referred to as spiritual understanding (Bishop & Scudder, 1990; Hall, 1997; Pesut, 2008; Pesut, Fowler, Taylor, Reimer-Kirkham, & Sawatzky, 2008). Spirit is a term derived from the Latin word for “breath” and “ breathing,” which are basic to sustaining life and being (Huebner, 1985).

The term spiritual is often associated with religion, a tradition that Hall (1997) identified as deriving from the fact that Western culture limits the expression of what is known either to science or to religion. Because of this, alternative conceptualizations of the spiritual have not been as visible as those that associate spirituality with religion. Many people do connect their spirituality with religious beliefs; however, that which is spiritual does not of necessity link with religiosity (Campesino & Schwartz, 2006; McSherry & Cash, 2004; Pesut et al., 2008; Tinley & Kinney, 2007). Rather, the spiritual is a complex combination of values, attitudes, and hopes that is linked to the transcendent and that guides and directs a person’s life. It is particularly associated with life experiences that bring one to the brink of uncertainty: the “existential boundary issues” of life and death, good and evil, hopes and dreams, and despair and suffering. Personal knowing, when it is thought of as being spiritual in nature, provides a way for people to understand and shape their lives as they confront difficult challenges. This form of spirituality helps people to face the inevitable realities of life that create vulnerabilities and that cannot be overcome. Spirituality nurtures a personal agency for relating to such vulnerabilities (Hart, 1997).

Hall (1997) presented a conception of human spirit and spirituality as reaching within to learn to accept, love, and value what you find there and learning to be yourself authentically and with confidence. What you find may not be what you want to find, but you either change or come to live with, accept, and love what is within. This spirituality is not a process of Self-centered exploration nor is it linear. Rather, it is an unfolding process that is grounded in the context of everyday experience in relationship with others.

Personal knowing as self-in-relation

Hall and Allan (1994) explained the vital link between personal knowing and relationships with others in their concept of Self-in-relation. Personal knowing and wholistic nursing practice are possible through Self-in-relation, which is the core of caring and healing. These authors’ ideas are grounded in traditional Chinese medicine, which philosophically views the mind, body, spirit, and environment as an integrated whole. The embodied Self is an open system that belongs to a social world. The caring relationships that nurses enter into can reflect four dynamics that nurture Self-in-relation:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree