Nursing’s fundamental patterns of knowing

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

It is the general conception of any field of inquiry that ultimately determines the kind of knowledge that field aims to develop as well as the manner in which that knowledge is to be organized, tested and applied. . . . Such an understanding . . . involves critical attention to the question of what it means to know and what kinds of knowledge are held to be of most value in the discipline of nursing.

Barbara A. Carper (1978, p. 13)

This quote from Barbara Carper underscores that, in the field of nursing, what we believe our disciplinary focus to be will determine what we value as knowledge and how we go about developing that knowledge for our practice. At first, the quote seems to state the obvious: the things that we believe we should develop knowledge about or that we feel to be valuable will determine what our knowledge development products eventually are. The importance of the quote is that it makes what we value—not what we produce as knowledge—centrally important.

Think about it: what do you believe nurses need to know? Do you find your answer to be grounded in what you or the profession values? Although the question of what nurses need to know is a very broad one, perhaps some of the things that come to mind are how to ease pain and suffering, how to artfully accomplish hurtful procedures, and how to best interact with families during times of crisis.

Now think about all that you need to know when you are easing the pain of a child who has been severely burned. Wouldn’t you need to know more than what you have learned from books, articles, and teachers? There are a whole host of things to know that you cannot learn before you are in a specific situation with a specific patient. For example, you cannot know whether this particular child is more fearful of male than female nurses until you begin to care for the child. In short, there are many situational factors that collectively affect pain relief that must be considered and that reside in each unique situation. Consider such things as nuances of personality, individual responses to pain alleviation that you cannot know until you begin a management regime, a parent’s fear that his or her child may become addicted to pain medications, and your unanticipated degree of intolerance for moral distress when pain is not relieved and an ordering provider will not change dosing requirements. All of these factors need to be considered in this particular situation for pain to be eased for this child, but none of these things were knowable until you began to provide care for this patient.

This text challenges you to think broadly, to deliberately consider what you need to know to be an effective nurse, and to think about the values in which such knowing is grounded. This chapter begins with Carper’s quote and examines five patterns of knowing as a basis for considering the value of multiple forms of knowledge and knowing in nursing. It provides an overview of Carper’s (1978) four fundamental patterns of knowing in addition to discussing knowing and knowledge within the pattern of emancipatory knowing developed by Chinn and Kramer (2008).

Knowledge for a practice discipline

Carper’s (1978) patterns of knowing include traditional ideas of empiric knowledge as well as knowing and knowledge that is personal, ethical, and aesthetic in nature. Chinn and Kramer’s (2008) pattern of emancipatory knowing focuses on developing an awareness of social problems and taking action to create social change. Although we believe that knowledge and knowing within all patterns are required for effective nursing care, empirics has been and continues to be a major focus for all health care disciplines, including nursing (Paley, Cheyne, Dalgleish, Duncan, & Niven, 2007; Porter, 2010; Satterfield et al., 2009). Understanding knowledge for nursing practice as something more inclusive and broader than empirics is, in our view, critical for a practice discipline.

Nursing involves processes, dynamics, and interactions that are most effective when the five knowing patterns of empirics, ethics, aesthetics, personal knowing, and emancipatory knowing come together. Praxis is possible when all patterns of knowing are integrated in a way that supports social justice. The term praxis is not just a fancy word for “practice.” A nurse who follows orders and thoughtfully completes an ordered treatment such as wound irrigation is practicing and indeed may be practicing well. To be engaged in praxis, however, requires the nurse to move beyond just practicing and to engage in processes that undo any social inequities that he or she finds to be present in the health care environment.

To illustrate each of the patterns of knowing, consider a young woman—we’ll call her Nayan—who has a gunshot wound that requires wound irrigation. In the context of this treatment, the nurse will surely be thinking about more than just aseptically irrigating this patient’s wound (a procedure grounded in empirics). He might be wondering about the ethics of advising Nayan to get rid of her pistol because she lives in a tough neighborhood where her life is endangered, although ethically he certainly cannot omit this treatment any more than he can ignore aseptic procedures. He may be keeping his personal feelings about guns in check, because he realizes that his biases may affect his approach and the subsequent trust that Nayan has in him. This nurse is probably considering how to finesse or orchestrate the treatment in the way that makes it as effective as possible, which falls within the realm of aesthetics. Aesthetic knowing would include sensing how vigorously to irrigate the wound for effectiveness without creating unnecessary discomfort and then continually modifying the approach as the irrigant is applied in response to how Nayan responds. For example, it is aesthetic knowing that lets the nurse know that he needs to decrease the irrigation pressure when he sees the patient grimace or to distract Nayan from focusing on it so that he can create a situation where the irrigation procedure is minimally uncomfortable but still effective.

Emancipatory knowing requires the nurse to thoughtfully reflect and act in relation to a treatment and its implications in a way that makes things better for the future, not just for Nayan at this particular moment but for society in general. It is this reflection and action that we call praxis. In this example, the very existence of a needless gunshot wound that requires irrigation and that involves lost wages and additional expenses for this young woman is considered. Praxis means that the nurse considers the situation and does something about it. Praxis may come in the form of political action, such as joining in a letter-writing campaign or lobbying about limiting or not limiting access to guns; working to increase the safety of neighborhoods so that guns are not needed; or championing programs to promote the safe handling of guns. Thus, emancipatory knowing would lead this nurse to do something broader about gunshot wounds in an effort to stop them from occurring in the first place. We do not mean to imply that praxis should come out of each and every nursing encounter. What we do imply is that, in the context of practice and within the professional community, it is important to be aware of situations of injustice, to raise everyone’s awareness of injustices, and to reflect on these situations and act to improve them whenever possible.

In the remainder of this chapter, we provide more detail about the nature of knowledge forms and about the knowing processes that are unique to each pattern. Each pattern involves distinct processes for developing knowledge. These processes are located within five dimensions: (1) critical questions and (2) creative processes that initiate and generate knowing and knowledge; (3) formal and (4) integrated practice expressions of knowledge and knowing; and (5) authentication processes that are used to examine and improve knowledge for the discipline.

Although for a complete understanding each pattern must be considered separately, we return again and again to the complementarity of the processes within each pattern and their contribution to the whole of knowing. We also shun the unquestioned use of rules, methods, and principles often associated with knowledge development and embrace perspectives that value knowledge development that is grounded in creating an envisioned future.

Finally, this chapter presents an example of pattern disintegration that we call “patterns gone wild,” which occurs when any one pattern is taken out of the context of the whole. We close this chapter by presenting a case for knowledge development that encompasses all knowing patterns.

Knowing and knowledge

In the context of this text, the term knowing refers to ways of perceiving and understanding the Self and the world. The term knowledge refers to knowing that is expressed in a form that can be shared or communicated with others. The “knowledge of a discipline” is knowledge that has been collectively judged by standards that are shared by members of the disciplinary community and that is taken to be a valid and accurate understanding of elements and features that comprise the discipline. The epistemology of a discipline refers to the ways in which knowledge is developed. Epistemology is the “how to” of knowledge development. The types of knowledge that are most important for nursing are epistemologic concerns.

Alternatively, knowing is a more elusive concept. Knowing is fluid, and it is internal to the knower. People know things as a result of interactions with multiple sources: from what they are taught by others, from books, from their own thinking and experiential processes, from the subconscious absorption of background societal directives (e.g., the nature of personal space), and from many other sources. People “know” more than they can ever express formally as knowledge. For example, try to explain what an onion tastes like to someone who has never eaten onions or to fully explain fully how you, as an expert nurse, managed a difficult clinical situation. Not only is your experience of onions or nursing expertise personal to you, but you also cannot fully impart the nature of these experiences to others. However, you do know what an onion tastes like and that you managed that nursing situation well. In this way, knowing is a concept that is linked to ontology or a way of being; it is particular and unique to our existence and to each individual’s personal reality.

As they practice, nurses make use of insights and understandings gained from a variety of sources that they often take for granted and that they do not consciously think about. Much of what they know is expressed through actions, movements, or sounds in a fluid nursing situation. What is conveyed in a nurse’s actions is a simultaneous wholeness or “whole of knowing” that textbooks and theories can never portray. This whole of knowing that happens in practice can only exist in the moment, and it is typically not available to a broader audience.

To summarize, knowing is a particular and unique awareness that grounds and expresses the being and doing of a person, whereas knowledge is knowing that can be expressed and communicated to others in many forms, including principles of practice, works of art, stories, and theories. Disciplinary knowledge is knowledge that has been judged to be pertinent to the focus of a discipline by its members.

We believe that much of what nurses know has the potential to be more fully expressed and communicated than it has been in the past and that this can happen when all patterns of knowing are valued. Formal descriptions and theories that are used to convey empiric knowledge will only partially reflect the whole. However, when you move beyond the traditional limits of empirics and consider representing knowing within the aesthetic, ethical, personal, and emancipatory patterns, it is possible to convey a more complete picture of what is known within the discipline as a whole. When the knowledge picture is more complete, its value can be more openly assessed and embraced.

Sharing knowledge is important because it creates a disciplinary community beyond the isolation of individual experience. When this happens, social purposes form, and knowledge development and shared social purposes can form a cyclic interrelationship that moves us toward the prospective, value-grounded change that emerges from praxis.

Overview of nursing’s patterns of knowing

Since Florence Nightingale first established formal secular education for nurses, nursing has depended on formal knowledge as a basis for practice. The nature of knowledge changes with time, but the fundamental values that guide nursing practice have remained remarkably stable (Clements & Averill, 2006; Fawcett, 2006).

Barbara Carper’s (1978) examination of the early nursing literature resulted in the naming of four fundamental and enduring patterns of knowing. She called the familiar and respected pattern of empirics the science of nursing. She spoke of ethics as the component of moral knowledge in nursing; personal knowing in nursing was knowledge of the Self and others in relationship; and aesthetics was described as the art of nursing. As noted previously, we have developed the pattern of emancipatory knowing as a fifth pattern. The fundamental patterns of knowing as identified by Carper were valuable in that they conceptualized a broad scope of knowing that acknowledged knowing patterns beyond the limited boundaries of empirics.

The empiric knowing pattern has been a central focus for knowledge development within the nursing discipline. The emancipatory, ethical, personal, and aesthetic patterns have not been as well developed, which reflects a neglect of these patterns of knowing and an overvaluing of empirics as the knowledge of the discipline (Fawcett, 2006; Fawcett, Watson, Neuman, Walker, & Fitzpatrick, 2001). However, methods for developing knowledge related to emancipatory, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowledge are beginning to be systematically described. The appearance of a literature devoted to additional knowing patterns underscores the value of a broader scope of knowing and knowledge in practice (Clements & Averill, 2006; Cloutier, Duncan, & Bailey, 2007; Fiandt, Forman, Megel, Padieser, & Burge, 2003; Gramling, 2006; Lane, 2006; Porter & O’Halloran, 2009; Weis, Schank, & Matheus, 2006; Wittmann-Price & Bhattacharya, 2008). Because of this shift, in this and subsequent chapters, we first discuss emancipatory knowing; this is followed by ethics, personal knowing, and aesthetic knowing, and it ends with our conceptualization of the more traditional approaches to empiric knowledge development.

We provide an overview of our conceptualization of each of the patterns of knowing in nursing in the following chapter sections. We have extended the understanding of Carper’s descriptions on the basis of our ideas, research, and the insights of other nursing scholars. In addition, the following sections introduce the methods that we propose for the development of each of the patterns.

Emancipatory knowing: the praxis of nursing

Emancipatory knowing is the human capacity to be aware of and to critically reflect upon the social, cultural, and political status quo and to figure out how and why it came to be that way. Emancipatory knowing calls forth action in ways that reduce or eliminate inequality and injustice. Awareness and critical reflection are essential to identify the inequities that are embedded in social and political institutions as well as to identify those cultural values and beliefs that need to change to create fair and just conditions for all. Emancipatory knowing requires an understanding of the power dynamics that create knowledge and of the social and political contexts that shape and influence prevailing epistemologies of knowledge and knowing. Emancipatory knowing seeks freedom from institutional and institutionalized social and political contexts that sustain advantage for some and disadvantage for others.

Emancipatory knowledge, as an expression of emancipatory knowing, begins with an awareness of social problems such as injustices and questioning why they exist. This questioning leads to critiques of the status quo. These critiques lead to imagining the changes that are needed to create equitable and just conditions that support all humans in reaching their full potentials. Formal written expressions of emancipatory knowledge (e.g., action plans, manifestoes, critical analyses, vision statements) describe the conditions that limit human potential, the circumstances that create and sustain those conditions, what is required to change the status quo, and what needs to be created in place of the status quo. Emancipatory knowledge is also expressed in activist projects that are directed toward changing existing social structures and establishing practices and structures that are more equitable and favorable to human health and well-being.

The integrated expression of emancipatory knowing is praxis, which produces changes that are intended to be for the benefit of all. We emphasize “integrated,” because the action and reflection of true praxis must be grounded in all knowing patterns to be effective. To illustrate emancipatory knowing, we return to our example of the nurse who is caring for the young woman with the gunshot wound. To have had some awareness that this situation was not only unnecessary but also unjust, the nurse had to be aware that Nayan’s need for aseptic wound irrigation (which requires empirical knowing) was in part the result of the city shifting police resources from poorer to wealthier neighborhoods (an ethical issue). The nurse would also have had to know that—if he were going to have any influence on this young woman with regard to the safe handling and use of guns, removing guns from the home, or encouraging Nayan to speak out politically—his counsel and teaching would have to be performed with a consideration of Nayan’s and her family’s feelings about weapon use, Nayan’s safety needs (aesthetic knowing), and his own bias regarding gun control (personal knowing).

Although this is a simple example, it illustrates that emancipatory knowing is integrated with the four knowing patterns when the nurse encourages the young woman to speak out politically about the situation in her neighborhood. In addition, praxis at the community level would occur when the nurse teams up with friends and peers to work with community leaders to improve police patrol in underserved neighborhoods.

Praxis at the individual level occurs when people recognize conditions that unjustly limit their own or others’ abilities and experiences, reflect on these situations with a growing realization that things could be different, and take action to change the circumstances of their own and others’ lives. As actions are taken, individuals remain continually attuned to the ideals that they seek, and they continue to critically reflect and act to transform experience into the imagined ideal.

Praxis as a collective endeavor requires reflection and action in concert with others who are engaged in creating social and political change. When groups of people collectively share their individual insights and experiences, critiques and imaginings become symbiotic, and possibilities for change multiply. When members of a discipline such as nursing engage in praxis at a collective level, their cooperative reflections and actions can create substantial change. Praxis within a disciplinary collective also creates emancipatory knowledge that can be authenticated and understood by members of the discipline.

As a community of critical reflectors and actors, nurses can begin to act on their insights and move toward the goal of transforming nursing and health care. In this way, the critical reflections and actions that constitute praxis at the individual and collective level continue to energize change in the direction of creating emancipatory knowledge that makes visible how equitable and just social structures can be created. The cycle of praxis (i.e., action and reflection to undo unjust social practices) and the emancipatory changes that it produces are ongoing processes. As praxis produces change, that change undergoes further action and reflection in relation to the envisioned outcome.

Ethics: the moral component of nursing

Ethics in nursing is focused on matters of obligation: what ought to be done. The moral component of knowing in nursing goes beyond knowledge of the norms or ethical codes of conduct: it involves making moment-to-moment judgments about what ought to be done, what is good and right, and what is responsible. Ethical knowing guides and directs how nurses morally behave in their practices, what they select as being important, where their loyalties are placed, and what priorities demand advocacy.

Ethical knowing also involves clarifying conflicting values and exploring alternative interests, principles, and actions. There may be no satisfactory answer to an ethical dilemma or moral distress; rather, there may only be alternatives, some of which are more satisfactory than others. Ethical knowing in nursing requires an experiential knowledge of social values and mores from which ethical reasoning arises as well as knowledge of the formal principles and codes within the discipline (Carper, 1978).

Ethical principles and codes are formal expressions of ethical knowledge that reflect the philosophic ideals on which ethical decisions rest. Ethical knowledge does not describe or prescribe what a decision or action should be. Rather, it provides insight about which choices are possible and direction with regard to choices that are sound, good, responsible, and just.

Ethical knowledge forms are like empiric theory and formal descriptions in that they are expressed in language, reflect some dimensions of experience, and express relationships among phenomena. However, empiric theory relies on observations that can be tested or confirmed by others in a more or less objective manner. Ethical codes and principles cannot be tested in this sense, because the relationships expressed in codes and principles rest on underlying philosophic reasoning that leads to conclusions that concern what is right, good, responsible, or just. This means that reasoning processes—rather than an appeal to facts or observational data—authenticate ethical knowledge. The reasoning can include descriptions that substantiate an argument, but the conclusions are value statements that cannot be perceived or confirmed empirically. The integrated expression of ethical knowing is moral and ethical comportment, which requires the nurse to practice in a way that integrates disciplinary knowledge and situational factors to achieve a morally acceptable result.

Personal knowing: the self and other in nursing

Personal knowing in nursing concerns the inner experience of becoming a whole, aware, genuine Self. Personal knowing encompasses knowing one’s own Self as well as the Self in relation to others. As Carper (1978, p. 18) stated, “One does not know about the self, one strives simply to know the self.” It is through knowing one’s Self in a nonobjectified way that people are able to know the other. Full awareness of the Self in the moment and in the context of interaction makes possible meaningful, shared human experience. Without this component of knowing, the idea of the therapeutic use of the Self in nursing would not be possible (Carper, 1978).

Personal knowing is most fully communicated as an authentic, aware, genuine Self. Other people perceive the existence of a unique person by physical characteristics, but they also come to know each person as having a unique personality. As personal knowing emerges more fully throughout life, the unique or genuine Self can be more fully expressed and thus becomes accessible as a means by which deliberate action and interaction take form. A deliberate effort to understand the Self through the cultivation of personal knowing increases personal authenticity and genuineness.

Authenticity as a person is important for the provision of sound nursing care. Authenticity requires questioning, acknowledging, and understanding such things as personal biases, strengths and weaknesses of character, feelings, values, and attitudes. After these things have been acknowledged and understood, the nurse can work toward reconciling and resolving inner conflicts of the Self that compromise best nursing practices. In this way, the inner knowing of the Self grows, and authenticity increases.

For example, suppose you hold a negative bias against a certain group of persons. For this example, we will use older adults. Unless you address personal knowing by acknowledging and understanding your bias, you are forced into inauthenticity (e.g., “I’m trying to like this old person even though I don’t”) when in contact with frail elders. Willfully changing a bias that you have grown up with and learning to recognize actions that reflect this bias are major life-long processes that cannot be accomplished easily. However, when you face your bias and acknowledge that it is preventing you from being genuinely present as a nurse when you care for older people, you can deliberately choose to bring forth your desire to be genuinely present with such individuals in a nursing situation. Your actions will reflect that intention, and your bias will fade into the background. When you are genuine with older people, you also come to a place in which you can begin to see older people in a more positive light. You become more comfortable working with elderly persons, and, as a result of your encounters with them, you continue your own Self-healing journey. Your actions are motivated from an intention to provide good care. In short, the key to cultivating personal knowing is to recognize your inner Self as fully as possible and to choose those aspects of the Self that best serve your intentions as a nurse.

It is possible to describe certain things about the Self with the use of personal stories that are written expressions of personal knowing. These descriptions provide sources for deep reflection and a shared understanding of how personal knowledge can be developed and used in a deliberative way. Descriptions of the Self portrayed in personal stories are limited in that they never fully reflect personal knowing, and they are retrospective in that they can describe only the Self that was. However, publicly expressed descriptions can be a tool for developing Self-awareness and Self-intimacy and for communicating to others valuable possibilities for developing personal knowing (Hagan, 1990; Nelson, 1994). In addition to public descriptions of personal knowing, the genuine Self is expressed through our daily being in the world. This in-person, ongoing type of expression defies complete description, but it is nonetheless a formal expression of personal knowing.

In a sense, all knowing is personal; individuals can know only through their personal experience (Bonis, 2009). For example, empiric theories can be learned, but their meaning for the individual comes from personal meaning and experience with the phenomena of the theory. Ethical codes and moral beliefs are likewise personal in nature. We recognize the broad meaning of personal knowing, but our focus is on the aspect of personal knowing that evolves from processes for knowing the Self and for developing and growing in Self-knowing through healing encounters with others. It is knowing the Self that makes the therapeutic use of the Self in nursing practice possible.

Aesthetics: the art of nursing

Aesthetic knowing in nursing involves an appreciation of the meaning of a situation and calls forth inner resources that transform experience into what is not yet real, thus bringing into being something that would not otherwise be possible. Aesthetic knowing makes it possible to move beyond the surface to sense the meaning of the moment and to connect with human experiences that are unique for each person: sickness, suffering, recovery, birth, and death. Aesthetic knowing in practice is expressed through the actions, bearing, conduct, attitudes, narrative, and interactions of the nurse in relation to others. It also is formally expressed in art forms such as poetry, drawings, stories, and music that reflect and communicate the symbolic meanings embedded in nursing practice.

Aesthetic knowing is what makes possible knowing what to do and how to be in the moment, instantly, without conscious deliberation. Carper (1978) characterized aesthetic knowing as abstracted particulars. In other words, aesthetic knowing is having an understanding of those particular features of a situation that come from a direct understanding of what is significant and meaningful in the moment. The nurse’s sense of meaning in the situation is reflected in the action taken. Meaning among those in the situation is often understood and shared without a conscious exchange of words, and it may not be consciously or cognitively realized; it may be occurring the background of the situation and not consciously thought about or considered.

Sometimes what a situation means to the nurse comes from the nurse’s own perspectives, which makes it possible for the nurse to share new meanings and possibilities for managing a given situation with others. These new meanings and possibilities can be rehearsed, which provides experience with possible movements and verbal expressions that can be used in future situations. Within the pattern of aesthetics, the nurse’s actions take on an element of artistry and create unique, meaningful, and often deeply moving interactions with others that touch the common chords of human experience. We refer to this aspect of nursing practice as the transformative art/act. We use the notion of art/act to convey that nursing is art in action. A nurse who practices artfully is acting in a way that transforms what is into what could be; a nurse who is acting transformatively is artful. In short, the term art/act is used to convey the notion that clinical nursing is simultaneously an art and acting or doing.

Aesthetic knowing is expressed in the moment of experience-action (Benner, 1984; Benner & Wrubel, 1989) in the transformative art/act. As an example, imagine a nurse who enters a clinic examination room and sees a young woman sitting on the examination table. Immediately, from an integration of contextual factors such as body language and facial expression, the nurse understands that the young woman is fearful; the nurse’s facial expressions and movements confirm to the young woman that the nurse understands that she is afraid. The woman relaxes and looks at the nurse; the nurse places her hand on the young woman’s shoulder and smiles. In this example, nothing was said, but the nurse entered the room and immediately grasped the meaning of the situation (i.e., the young woman’s fear and the need to relieve it). The ongoing mutual reading of meanings that occurred very quickly between the nurse and the client resulted in a transformation of the situation for the client from one of fear to one of safety. Transformative art/acts such as these constitute a form of performance art.

Aesthetic knowledge is formally expressed in aesthetic criticism and in works of art that symbolize experience. Aesthetic criticism is a written expression of aesthetic knowledge that conveys the artistic aspects of the art/act, the technical skill required to perform the art/act, the knowledge that informs the development of the art/act, the historical and cultural significance of specific aspects of nursing as an art, and the potential for the future development of the art form.

Empirics: the science of nursing

Empirics is based on the assumption that what is known is accessible through the physical senses, particularly seeing, touching, and hearing. Empirics can be traced to Nightingale’s precepts regarding the importance of accurate observation and record keeping. Empirics as a pattern of knowing is grounded in science and other empirically based methodologies. By this it is meant that science as a process makes use of empirically based methods to generate knowledge. Empirics assumes that an objective reality exists and that truths about it can be understood through inferences that are based on observations and understandings that are verifiable or confirmable by other observers. In other words, empirics assumes that what many people observe and agree upon is an objective truth.

Empiric knowing is expressed in practice as scientific competence by means of competent action grounded in empiric knowledge, including theory. Scientific competence involves conscious problem solving and logical reasoning, but much of the underlying empiric knowing that informs scientific competence remains in the background of awareness. What remains in the background usually can be brought to awareness when attention turns to the reasoning process itself. In other words, when completing the wound irrigation from our earlier example, the seasoned nurse does not consciously think about the empiric knowledge that justifies the requirement of asepsis as he performs the procedure. However, he could explain the scientific basis for asepsis if asked to do so.

Empiric knowledge is formally expressed in the form of empiric theories, statements of fact, or formalized descriptions and interpretations of empiric events or objects. The development of empiric knowledge traditionally has been accomplished by the methods of traditional science. This has often involved testing hypotheses derived from a theory that offers a tentative explanation of empiric phenomena. Many types of formal descriptions and theories that express empiric knowledge in nursing are linked to the traditional ideas about what is legitimate for developing the science of nursing. In addition, newer methods have been developed to include activities that are not strictly within the realm of traditional empiric methodologies, such as phenomenologic or ethnographic descriptions or inductive means of generating theories and formal descriptions.

Processes for developing nursing knowledge

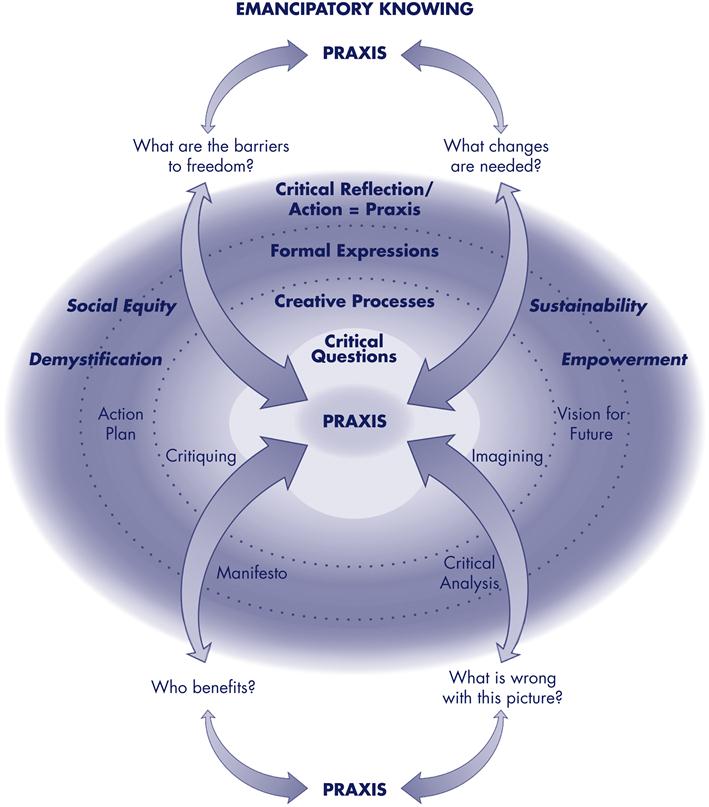

Figures 1-1 and 1-2 illustrate the interrelationships among each of the patterns of knowing. Figure 1-1 focuses on emancipatory knowing, whereas Figure 1-2 details the four fundamental patterns that were originally described by Carper. As shown in Figure 1-1, emancipatory knowing surrounds and connects with each of the four fundamental patterns of knowing. The four fundamental patterns are represented in the figure by the central, light-colored, irregular oval (yellow on the color plate inside the front cover) with praxis at its core. Because the pattern of emancipatory knowing focuses on matters of social justice and equality, it is configured as surrounding and encompassing ethical, personal, aesthetic, and empiric knowing. Embedding the four fundamental knowing patterns within emancipatory knowing also symbolizes the need to examine and understand both practice and disciplinary approaches to knowledge development in relation to how they enable praxis and emancipatory change.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree