CHAPTER 16 Persistent pain in the older person

FRAMEWORK

This chapter offers a comprehensive view of pain and pain management for older people. The need for proper assessment and measurement of pain is addressed and the importance of self-reporting where possible is considered more reliable than reliance on surrogate reporters. Older people who have dementia are at risk of having pain unrecognised and untreated. The impact of pain on social and mental capacity must be recognised and pain from chronic disease often leads to depression and other clinical problems that need to be considered. The authors offer a continuum of chronic pain management service requirements that illustrate the complexity of pain treatment. A broad approach that includes non-pharmacological intervention is supported but the need for an interdisciplinary team who understand aged care as well as pain management is a more effective way to achieve quality outcomes. [RN, SG]

Introduction

Pain is recognised as being a complex and inherently personal experience with dimensions that are sensory-discriminative (e.g., location, intensity, quality of sensation), affective-motivational (e.g., unpleasantness, anxiety, actions to withdraw-avoid further harm), and cognitive-interpretive (e.g., meaning of pain symptoms, context, beliefs). Pain may be considered as being either acute (short-term, resolves with the cessation of noxious stimulation or recovery from injury/disease) or chronic, persistent pain. Chronic pain should not be regarded as a simple perpetuation of an acute pain episode. Rather, modern conceptualisations of pain emphasise a biopsychosocial perspective in which biological, psychological, behavioural, and social factors all play a relevant role in shaping the experience (Turk & Flor 1999). Common factors associated with chronic pain include: interference and disability, mood disturbance, problems with sleep, effects of disuse, poor quality of life, and a high and ongoing consumption of treatments, as well as adverse side effects and iatrogenesis resulting from past treatment attempts to provide a cure for pain. As pain persists beyond the usual time of healing, the original injury or pathological cause often becomes less important than the ongoing pain and suffering. In other words, the pain becomes the major problem needing timely treatment. Indeed, there is now growing recognition of chronic pain as a disease entity in its own right (Niv & Devor 2004; Siddall & Cousins 2004). Considerable progress has been made in understanding the basic pathophysiology of pain processing and the role of selected psychological and social factors that impact on the perceptual experience. The development of new and more targeted pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment strategies for management of pain has also been forthcoming over recent years as our fundamental knowledge about pain has improved. Nonetheless, the assessment and management of bothersome pain can be a particularly challenging prospect, and in none more so than those of advanced age.

Epidemiology of pain in older persons

Epidemiologic studies of pain prevalence in the community show that acute pain remains approximately similar across different age cohorts at 5% of the population (Helme & Gibson 2001). In contrast, persistent pain (defined as pain on most days persisting beyond 3 months) shows an age-related increase in prevalence until at least the 7th decade of life and then a slight decline into very advanced age (Blyth et al 2001; Helme & Gibson 2001; Jones & Macfarlane 2005). Prevalence rates of persistent pain vary widely between different studies, nonetheless, a consensus view might suggest that about 18% of young adults suffer from persistent, bothersome pain rising to a peak of 30–65% in those aged 55–65 years and then declining somewhat to about 25–55% of the population in those aged 85 years and above (Blyth et al 2001; Gibson 2007; Helme & Gibson 2001; Jones & Macfarlane 2005). This age-related increase in pain prevalence is perhaps expected given that the highest rates of painful degenerative disease are found in the older segments of the population.

The unexpected drop in pain prevalence during very advanced age is more difficult to understand, as the rates of injury and disease continue to climb over the entire adult lifespan. Evidence from retrospective case reviews of acute and chronic medical conditions (e.g., peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, pneumonia, heart attack or angina, post-operative pain, cancer and osteoarthritis) reveals an often atypical presentation in older adults, characterised by an absence of pain as a major symptom or a reduction in self-reported pain intensity (Gibson & Helme 2001; Pickering 2005). There is limited evidence of age-related alterations in the function of the pain pathways (Gibson & Farrell 2004) and the older person may be more stoic or accepting of mild aches and pain, and dismiss the presence of pain as part of the normal ageing process (Yong et al 2001, 2003). Collectively, these changes may partly compromise the early warning functions of pain and lead to the systematic under-reporting of mild pain. Other possible explanations for the unexpected drop in pain prevalence include a survivorship effect, whereby only the most healthy pain-free individuals survive into very advanced age; a sequestration of those with the most bothersome pain into residential aged care facilities, removing them from community-based pain prevalence studies; or simply that older people choose to avoid musculoskeletal pain by adopting a more sedentary lifestyle (Helme & Gibson 2001). Despite the slight reduction in pain report during very old age, it is important to recognise that when pain is reported, it is no less intense or bothersome for the individual who suffers.

A number of studies show an exceptionally high prevalence of pain (80%) in older adults living in residential aged care facilities (Helme & Gibson 2001; Parmelee et al 1993). There is some evidence to suggest that the frequency of identified pain may be less in those with dementia (Ferrell et al 1995; Parmelee et al 1993), although this may simply reflect inadequate pain assessment strategies, as a recent study has shown no difference in the brain response to noxious stimulation in those with Alzheimer’s disease (Cole et al 2006).

Comprehensive assessment and measurement of pain in the older person

Whether pain is acute or chronic, it is important to develop a picture of all factors that may contribute to the pain, including the role of physical pathologies, documentation of aggravating and relieving factors, prior history, and consideration of relevant medical issues as well as the prospect of remedial or curative actions. With chronic pain, a comprehensive approach is also required, including the evaluation of physical functioning (disability, interference with daily activities), psychosocial function (mood, interpersonal relationships, sleep, cognitive function), beliefs and attitudes to pain (fear of harm, ability to cope, meaning of symptoms), and general quality of life. Each of these aspects of a comprehensive assessment are important in designing a tailored pain management program to meet the specific needs of the older individual and are important indicators of the efficacy of an integrated treatment approach (Herr 2005).

The key components of the medical assessment of chronic pain in the older person include:

The patient’s self-report, through a structured history that ascertains onset, location, intensity, periodicity, quality, aggravating and relieving factors, and impact of pain, should be the standard first step in pain assessment whenever possible (American Geriatrics Society [AGS] 2002, Herr 2005). The older person should be given every opportunity to provide this history notwithstanding the presence of communicative and/or cognitive impairment. The person taking the history should be a skilled communication partner, and necessary time, proximity, lighting, and sensory assistive devices should be utilised.

Individuals with mild to moderate cognitive impairment often remain capable of valid self-report (Ferrell et al 1995), especially in relation to current pain (Herr 2005), and these self-reports appear to be more reliable than the alternative of turning to the opinions of surrogate reporters regarding the patient’s pain experience (Horgas & Tsai 1998; Weiner et al 1999). The pain history should also encompass information about past pain-directed investigations, treatments, and their tolerability and effectiveness.

If not directly contributing to the underlying cause of their pain, concurrent illnesses may also be associated with other symptoms, impairments and disabilities (e.g., insomnia, weakness, falls) that can exacerbate or be relevant to the clinical presentation, cause and management of the pain (Leong et al 2007). In addition, it is important to evaluate all medications that the patient is already taking, especially in the context of renal or hepatic disease, alertness, cognitive impairment, balance problems, and general frailty, since the available pharmacological pain treatment options may become much narrower.

The physical examination should include specific focus on the site(s) of reported pain for any evidence of diagnostic clues, such as inflammation or other local changes, as well as the mapping out of the area of pain (Hadjistavropoulos et al 2007) particularly in relation to patterns of neuroanatomical distribution. Generally the focus is on the musculoskeletal system (e.g., evidence of spinal or large or small joint deformity and restriction of movement, or pain evoked by movement) and neurological systems (e.g., evidence of weakness, or sensory changes such as allodynia, hyperalgesia, or hyperpathia) (AGS 2002). Initial physical assessment should also evaluate the older person’s mobility and ability to carry out activities of daily living, and the impact of pain on these activities (AGS 2002).

Even mild impairment of memory and cognition is likely to have a significant impact on the assessment and management of pain (Ferrell et al 1995). Use of a validated screening instrument such as the ‘mini-mental state exam’ (MMSE) (Folstein et al 1975) reduces the likelihood of missing or underestimating cognitive loss.

Informed by the results of the history and examination, the clinician should consider the formulation including the likely diagnoses and contributions to the patient’s pain. If there has been a recent increase or change in pain report, the possibility that there is a new condition requiring specific treatment (e.g., a recent fracture or a deep vein thrombosis), should be pursued with appropriate diagnostic investigations. Other significant changes in a patient’s condition, such as unexplained weight loss, fever, or neurological signs may also indicate the need for further investigation. Metastatic disease should be considered in any person with a past history of malignancy. Last but not least, the clinician should not overlook opportunities for effective treatment through investigation that could lead to the diagnosis of a modifiable underlying disease process (e.g., joint arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, ischaemic pain responsive to stenting a blocked artery, or rheumatoid arthritis responsive to disease-modifying medication) (Australian Pain Society [APS] 2005). When considering whether to undertake any new investigations it is important to recognise the high prevalence of incidental pathology (e.g., radiographic osteoarthritis in the absence of symptoms) and abnormal findings may often be unrelated to the pain symptoms. The history and physical examination should guide the acquisition of additional diagnostic studies/tests and the need for such tests should be considered with care. Radiological imaging may reassure the patient that the pain is not due to serious pathology, enabling a focus on a rehabilitative approach. While identifiable pathology may be elusive in some older adults with chronic pain, the pain itself is a treatable disorder (Weiner et al 2004).

People with severe dementia

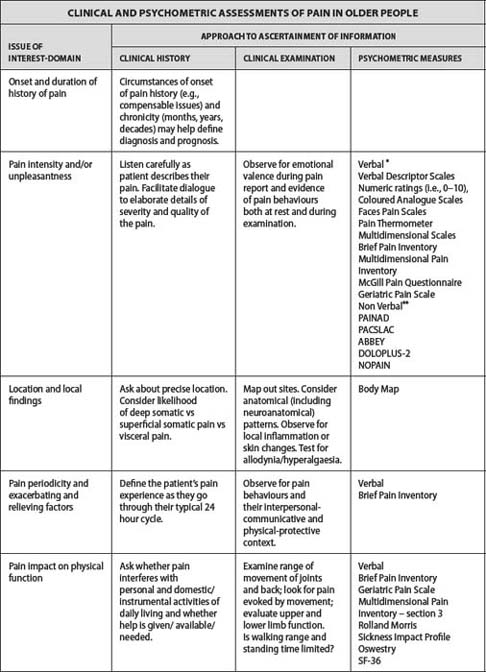

People with severe dementia are at significant risk of having their pain unrecognised and untreated (Morrison & Siu 2000; Teno et al 2003). They are also at significant risk of non-recognition of depression and sleep disorder, and significant correlations between measures of pain intensity, depression and sleep disturbance have been reported in a nursing home population both when applying self-report as well as behavioural instruments (Scherer et al 2007). Clinicians treating people with severe dementia are often faced with the challenge of balancing effective pain management without worsening cognitive function. It is unconscionable to leave a person suffering with pain where treatment is available. Medications may be cautiously introduced while monitoring pain, functional status and cognition. A comprehensive assessment approach to pain in older persons, including clinical history, clinical examination and psychometric measures, is presented in Table 16.1.

Psychometric approaches to a comprehensive assessment of pain

Measurement of pain

Self-report measures of pain have become the de facto gold standard for pain assessment and are recognised as being the only valid method to truly convey a latent, subjective state, which is really only known to the individual who suffers. Numerous unidimensional and multidimensional self-report measures of pain have been developed and, in general, tools with demonstrated merit in younger adult populations are also thought to be useful with older adults. Several different types of self-report scales exist, including verbal descriptors (i.e., none, mild, moderate, strong, severe), numeric ratings (i.e., 0–10), visual analogue scales in which current pain intensity is marked on a 10 cm line between extremes of ‘no pain’ and ‘worst possible pain’, complex qualitative word lists (i.e., MPQ), and more graphic representations, such as the Pain Thermometer, Coloured Analogue Scales or Pain Faces Scales (i.e., Baker Wong). Several studies to directly compare different self-report pain measurement tools suggest that the Verbal Descriptor Scales are most preferred by older persons and have the strongest evidence of utility, reliability, and validity (Herr 2005; Herr et al 2004; Mendoza et al 2004; Wynn et al 2000). Other acceptable measures include numeric rating scales (i.e., 0–10), box rating scales, pictorial pain scales (i.e., Pain Thermometer, Faces Scales), the multidimensional McGill Pain Questionnaire and Brief Pain Inventory (Gagliese & Katz 2003, Herr et al 2004, Pautex et al 2005). There is less uniform support for visual analogue scales and several authors raise concerns when using this measure with older adults (Gagliese & Katz 2003; Herr et al 2004). However, it is important to note that there is no one best measure of pain and a failure to complete one type of scale does not preclude success with other pain assessment tools (Ferrell 1995). In clinical practice it may be best to select tools that are consistent with the personal preference of the individual when it is known, or to try several different types of scales before giving up on the use of self-report tools.

Self-report pain assessment tools are still a viable option for many older persons with mild-moderate dementia (MMSE > 12) and there is a reasonable body of evidence to support the reliability and validity of many standardised, unidimensional pain assessment tools when used in those with dementia (Chibnall & Tait 2001; Herr et al 2004; Pautex et al 2005; Wiener 1999). Recognition of pain behaviours and observational indicators of pain are also a valuable component of pain assessment, in general, but become a crucially important aspect of the assessment as the patient’s capacity for self-report diminishes (Hadjistavropoulos 2005). In recent times, more than 10 new observer-rated behavioural pain assessment tools have been developed for specific use in those with dementia. Most instruments grade the presence of various behaviours that are thought to be indicative of pain. For instance, combinations of behaviours such as facial grimace or wince, negative vocalisation, changes in body language (rubbing, guarding, restlessness, etc.), and altered breathing or physiologic signs (heart rate, blood pressure, etc.) are scored to provide an index of likely pain intensity. Each new observer-rated scale has typically undergone some limited validation testing on a small sample of older adults and has demonstrated inter-rater reliability, although large methodologically rigorous studies are still needed to better establish the utility of these instruments (Hadjistavropoulos et al 2007). Recommended examples include the PAINAD, PACSLAC, ABBEY, and DOLOPLUS-2 behaviour rating scales (APS 2005; Herr et al 2006; Hadjistavropoulos et al 2007). These scales represent a welcome addition to the battery of available pain assessment tools and provide an important first step to improving the quality of pain management in this highly dependent and vulnerable group.

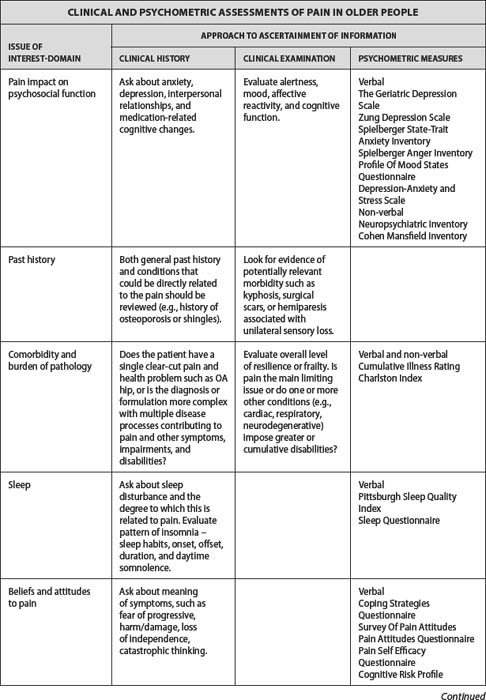

Measurement of psychosocial impacts of pain

The longer that bothersome pain persists, the greater the probability that the older person will become depressed, socially withdrawn, irritable, and somatically preoccupied. Anger, frustration, loss of ability to cope, and increased anxiety also occur as the person tries and fails with a variety of medical and non-medical therapies (Gibson et al 1994). As a result, the measurement of mood disturbance and social impacts are now considered as an integral component of any comprehensive clinical evaluation and should be incorporated as a routine part of the assessment plan.

There are a number of standardised tools that have demonstrated reliability and validity for use in older adults. The Geriatric Depression Scale, Zung Depression Scale, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and the Profile of Mood States Questionnaire are widely used and appropriate for older adult populations and particularly in those with chronic pain (Gibson 1997). The initial assessment can also include evaluation of other common psychological associations and mediators of pain, including anger (e.g., Spielberger Anger Inventory), cognitive and behavioural coping strategy use (i.e., Coping Strategies Questionnaire), beliefs and attitudes, stoicism (Survey of Pain Attitudes, Pain Attitudes Questionnaire) (Jensen et al 1987; Yong et al 2001), sleep (Menefee et al 2000), spousal bereavement and suicide risk (Gibson & Chambers 2003). Developing a better understanding of the person’s social situation, beliefs, attitudes and current coping strategies in relation to their pain provides an important starting point toward individualising the eventual management plan. However, there is a need for further evidence of reliability and validity of such scales when used in older persons, and the rich, comprehensive contextual information gained from such an assessment must be weighed against the increased respondent burden on the older person with bothersome pain.

Measurement of activity, disability and pain-related interference with daily activities

Chronic pain has a major impact on function and is likely to interfere with many of the activities of daily life (Williamson & Schulz 1992). A number of options exist for the measurement of activity levels or disability, ranging from objective measures of uptime/movement and direct observation of activity task performance, through to self-report psychometric questionnaires of activities of daily living and activity diaries. The psychometric scales typically used to measure function in geriatric populations (i.e., Barthel Index, Katz ADL Scale, Cape, Lawton & Brody, FIM) may be useful to monitor the personal and instrumental activities of daily living in the older person with chronic pain, although they tend to lack sensitivity and fail to measure the more discretionary activities that are mostly affected by chronic pain (i.e., leisure and pastimes, home maintenance, social interactions, gardening, and more strenuous activities). One must also exercise some care with the interpretation of activity measures, whether they be self-report or observational, because activity restriction can also occur as a consequence of a change in social circumstances, medical factors, or other concurrent disease states rather than as a consequence of pain (Gibson et al 1994). Moreover, regardless of whether measures are via self-report or objective markers, activity performance is highly dependent upon motivational factors and the context in which measurement is undertaken. As a result, studies of chronic pain populations have tended to focus on measures of perceived pain-related interference in activity or self-rated measures of perceived disability rather than documenting the actual levels of activity performance.

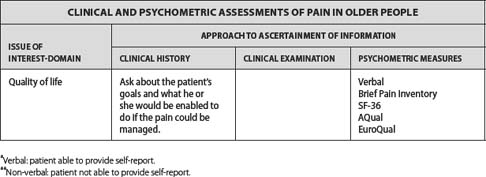

Validated measures of pain interference include the SF-36, Pain Disability Index, Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, the Sickness Impact Profile and a derived, abbreviated version called the Roland Morris Questionnaire. These instruments are multidimensional and typically monitor several domains of activity performance including ambulation, sleep and rest, mobility, self-care, social interaction, communication, work, emotional behaviours, and leisure activities and pastimes. The evidence for reliability and validity in older chronic pain populations is somewhat lacking, but all of these tools have been used in geriatric populations with good effect. It has been noted that older persons with chronic pain often respond more dramatically with respect to improvements in function than in pain intensity following an efficacious treatment plan (Cook 1998; Simmons et al 2002) and that functional outcomes are often considered as the most important outcome for the older person (Ersek et al 2003; Theiler et al 2002; Weiner et al 2003). For this reason, the measurement of disability and perceived interference should become an essential component of any routine comprehensive assessment.

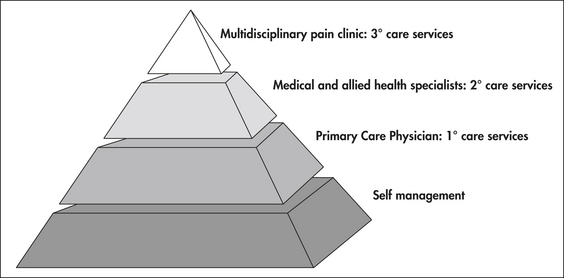

A comprehensive approach to treatment of chronic pain

While there is a very high prevalence of pain amongst older adults living in the community, many individuals are able to manage their pain with little or no help. This is particularly true in cases of short-term, mild aches and pains, where symptomatic relief may be all that is required. This type of pain will not be considered further in this chapter. In other cases, the pain may persist, although many older adults can still self-manage and remain high functioning (see Fig 16.1 below). For some, all that may be required is assistance from a primary care physician to gain symptomatic relief at times when pain is particularly problematic. Specialist help may be required if the pain persists and is bothersome or fails to respond to more conventional treatment strategies. Careful diagnosis of the pain (nociceptive, neuropathic and exacerbating factors), adoption of more advanced treatment methods (including the potential to modify disease components, such as arthroplasty in those with ongoing pain from osteoarthritis), and greater attention to the negative impacts of pain is typically required. Finally, there is a relatively small proportion of patients with chronic pain for whom pain becomes all-consuming and affects all aspects of life. The complexity of the chronic pain problem and the lack of response to standard treatments necessitate a different, more comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to evaluation and management.

Medical factors

If pain is identified to be a problem, then a decision needs to be made as to the balance between diagnostic evaluation and symptomatic management. In general, investigation should be limited to situations where the result has the potential to alter management or for the purpose of excluding serious pathology. A negative X-ray or scan may help reassure the individual, enabling the focus to shift to pain management. Unnecessary investigations can have a detrimental effect, moving the focus to the search for a cure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Modern conceptualisations of pain emphasise a biopsychosocial perspective.

Modern conceptualisations of pain emphasise a biopsychosocial perspective. Age-related increase in pain prevalence is perhaps expected given that the highest rates of painful degenerative disease are found in the older segments of the population.

Age-related increase in pain prevalence is perhaps expected given that the highest rates of painful degenerative disease are found in the older segments of the population. A number of studies show an exceptionally high prevalence of pain (80%) in older adults living in residential aged care facilities.

A number of studies show an exceptionally high prevalence of pain (80%) in older adults living in residential aged care facilities. The patient’s self-report should be the standard first step in pain assessment whenever possible.

The patient’s self-report should be the standard first step in pain assessment whenever possible. Individuals with mild to moderate cognitive impairment often remain capable of valid self-report.

Individuals with mild to moderate cognitive impairment often remain capable of valid self-report. Initial physical assessment should also evaluate the older person’s mobility and ability to carry out activities of daily living.

Initial physical assessment should also evaluate the older person’s mobility and ability to carry out activities of daily living.

People with severe dementia are at significant risk of having their pain unrecognised and untreated.

People with severe dementia are at significant risk of having their pain unrecognised and untreated. Verbal descriptor scales are most preferred by older persons and have the strongest evidence of utility, reliability, and validity.

Verbal descriptor scales are most preferred by older persons and have the strongest evidence of utility, reliability, and validity. Recognition of pain behaviours and observational indicators of pain are also a valuable component of pain assessment.

Recognition of pain behaviours and observational indicators of pain are also a valuable component of pain assessment. Measurement of mood disturbance and social impact should be incorporated as a routine part of the assessment plan.

Measurement of mood disturbance and social impact should be incorporated as a routine part of the assessment plan. One must exercise some care with the interpretation of activity measures, whether they be self-report or observational.

One must exercise some care with the interpretation of activity measures, whether they be self-report or observational. The measurement of disability and perceived interference should become an essential component of any routine comprehensive assessment.

The measurement of disability and perceived interference should become an essential component of any routine comprehensive assessment.

Multiple factors contribute to the lack of adequate treatment of pain.

Multiple factors contribute to the lack of adequate treatment of pain. The individual must be given adequate time to describe their symptoms.

The individual must be given adequate time to describe their symptoms.