Introduction

‘Maternal morbidity caused by perineal trauma can have long term social, psychological and physical health consequences for women. Perineal pain and discomfort may disrupt breastfeeding, family life and sexual relationships’ (RCOG, 2004).

Many women sustain perineal trauma when giving birth. Some perineal trauma will heal without intervention, while some will require suturing. The midwife is in a key position to offer advice and support, if necessary performing any necessary suturing or referring to a more specialist professional if required.

Incidence

- 85% UK vaginal deliveries result in perineal trauma (Kettle, 2002).

- Most perineal tears are second degree, varying from small and well aligned to extensive or complicated (Yiannouzis, 2002).

- In the first 3 months postpartum, approximately 23% women report dyspareunia, 19% report some urinary incontinence and 3–10% report faecal incontinence (RCOG, 2004).

- Most long-term symptoms are not reported to health professionals (RCOG, 2004; Bedwell, 2006).

- 0.5–2.5% of women sustain a third- or fourth-degree tear, with a small risk of recurrence in a subsequent vaginal birth of 4.5% (Byrd et al., 2005).

Facts

- Studies on suturing versus non-suturing second-degree tears have found no significant statistical differences between the two groups except on initial healing times (Metcalfe et al., 2006).

- Women report the experience of being sutured as highly unpleasant and those receiving local anaesthetic, as opposed to regional, report high levels of pain throughout the procedure (Saunders et al., 2002).

- The evidence suggests that using the correct repair material and suture technique will significantly reduce postnatal pain (Kettle & Johanson, 2006a, b).

- Performing a rectal inspection and examination prior to suturing will improve the detection of third- and fourth-degree tears (Andrews et al., 2005).

- Postpartum faecal and flatus incontinence are commonly (although not exclusively) associated with third- and fourth-degree tears.

- Episiotomy increases the incidence of more serious tearing including third- and fourth-degree tears, faecal incontinence, perineal pain and dyspareunia (Carroli & Belizan, 2004).

- Appropriate training has been linked to increased practitioner confidence, improved evidence-based practice and knowledge of anal sphincter injuries (Andrews et al., 2005) and thus should help reduce morbidity and associated litigation (RCOG, 2004).

- Regular pelvic floor exercises are effective in maintaining or reestablishing urinary continence (Chiarelli & Cockburn, 2002).

- Women appear to prefer their own midwife to conduct the perineal repair (Jackson, 2000).

Reducing perineal trauma

There are few studies on midwifery techniques to protect the perineum during spontaneous delivery (Eason et al., 2000). Factors such as primiparity, episiotomy, instrumental birth (especially forceps) and heavier babies are associated with greater trauma (Dahlen et al., 2006).

There is little practical evidence to inform modern midwifery practice on how to improve perineal outcomes. Evidence suggests that perineal trauma can be reduced by antenatal massage of the perineum in primigravida (Labrecque et al., 1999; Beckmann & Garrett, 2006) and continuous support in labour (Hodnett et al., 2003). There is some evidence of benefit in non-active pushing and a gentle, unhurried birth (Jackson, 2000; Albers et al., 2006), birth at home (Aikins Murphy & Feinland, 1998); also birth position may affect perineal outcome (Shorten et al., 2002) with the lateral birth position having the highest intact perineum rate and upright/squatting postures the lowest (Shorten et al., 2002; Bedwell, 2006). However, upright and hand and knees position (not squatting though) seemed to reduce trauma in one study (Soong & Barnes, 2005). Flexing the head (Bedwell, 2006) and invasive perineal massage in labour does not reduce trauma (Stamp et al., 2001).

(See also Chapter 1, p. 20, for more on prevention of perineal trauma.)

Assessment of perineal trauma

Prior to deciding whether suturing is required (see also Table 4.1), the genitalia should be examined using a good light source. On carefully inspecting the perineum if there is a moderate to large tear, it is thought best practice to perform a digital (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2007) and visual inspection of the anus to ascertain any anal involvement.

Table 4.1 Classification of perineal trauma.

- Injury to the labia varying from painful grazes to deeper – sometimes bilateral – labial lacerations which may require sutures

- Less commonly involves the anterior vagina, urethra or clitoris

- First degree: Injury to just the skin

- Second degree: Injury to the skin, vaginal tissue and perineal muscle. The trauma may be small, medium or large, long and deep; sometimes a branch tear (extending up both sides of the vagina)

- Third degree: Injury to skin, perineal muscle and involves the anal sphincter. Sultan (2002) suggests this can be subdivided into:

3a Partial tear of the anal sphincter

3a Partial tear of the anal sphincter 3b Complete tear of the anal sphincter

3b Complete tear of the anal sphincter 3c Internal sphincter also torn

3c Internal sphincter also torn- Fourth degree: Injury to the skin, perineal muscle and extending into the anal sphincter and rectal mucosa

- Consent must be obtained for this intimate and often uncomfortable examination, and entonox should be offered.

- Be gentle and careful, using wet gauze to part and inspect the labia, then vagina, then perineum, leaving the possible rectal examination until last.

- A third-degree tear may be visualised by parting the perineum where it meets the anus to see if the anal sphincter is intact, nicked or more seriously torn. On rectal examination, gently insert a lubricated, gloved finger into the anus and lift slightly to feel the surface of the rectum and anus, while also checking visually for a tear.

A perineal trauma measuring tool called the Peri-Rule™ has recently been developed. Its inventors suggest that objective assessment of the length and depth of perineal trauma will improve outcomes and reduce litigation (Metcalfe et al., 2006). However, an objective measurement of a tear does not guarantee the quality of the subsequent repair and the Peri-Rule has not been accepted uncritically by midwives.

Labial tears

The labia minora area is very sensitive and vascular: tears tend to heal well without stitches. However, sutures will be required if the tear continues to bleed or the trauma is fairly deep. Bilateral tears or grazes can result in both labia healing together and fusing. Warn the woman about this possibility and, whether or not bilateral trauma is sutured, suggest she gently parts the labia once a day, perhaps in the bath or shower, to minimise the danger of labial fusion.

First- and second-degree tears: to suture or not to suture?

The trend towards not suturing tears has evolved on the strength of limited evidence, and Yiannouzis (2002) suggests several reasons, including increased maternal choice, increased midwifery autonomy and staffing pressures. There have been various small studies involving non-suturing of first- or second-degree tears (Head, 1993; Lundquist et al., 2000; Fleming et al., 2003) and several larger studies (Langley et al., 2006; Metcalfe et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007). Midwives and women have strong views on which option they prefer, often resulting in difficulties in recruiting participants and staff compliance. in randomised studies. For example Metcalfe et al.’s study noted poor trial compliance: midwives did not suture one third of tears in the group randomised for suturing.

NICE (2007) recommends suturing for the following:

- First-degree tears if the skin is not well opposed.

- All second-degree tears.

However, this advice is based on very limited evidence from one small randomised controlled trial (Fleming et al., 2003). Since then other larger studies have emerged (Langley et al., 2006; Metcalfe et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007) and their findings are discussed below.

- All studies found a slower initial healing in the non-sutured groups. This difference was apparent in the immediate short-term period with poorer wound approximation and healing.

- The proportion of women with (subjectively assessed) ‘gaping’, asymmetrical or open perineal wounds was similar at 6 weeks between the groups in some studies (Langley et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007).

- Conversely, Fleming et al. (2003) and Metcalfe et al. (2006) found poorer wound approximation in some unsutured women at 6 weeks.

- Overall there were few statistical differences in secondary measures of pain, longer-term healing times, pelvic incontinence, infection rates and resumption of sexual intercourse (Langley et al., 2006; Metcalfe et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007).

Some clinicians have speculated that leaving the muscle layer unsutured could cause pelvic floor problems later on (McCandlish, 2001). Leeman et al.’s study on pelvic floor function found that weak pelvic floor exercise strength was more common with second-degree lacerations compared with an intact perineum, but did not differ between sutured and unsutured groups. Likewise, perineal body or genital hiatus (‘gape’) measurements did not vary between groups (Leeman et al., 2007).

To date there have been no randomised controlled trials of the quality and size to reach statistical power and draw clear evidence-based conclusions on the non-suturing of second-degree tears. Langley et al. (2006) suggest that while the balance of evidence tends towards suturing, it is based on limited and weak trials. So while midwives will no doubt hold a personal preference for a particular choice, it must be the woman who ultimately makes her feelings and preferences known, in light of the limited available evidence.

Non-suturing

- Offers women the opportunity to avoid the pain of being sutured (Lundquist et al., 2000).

- Results in slower initial healing and is more likely to have poor wound alignment.

- Some studies suggest no difference by 6 weeks post-birth; others observe poorer wound approximation in a small minority of non-sutured wounds at 6 weeks (Metcalfe et al., 2006).

Suturing

- Reduces uncertainty as this method is common practice.

- Enables faster initial healing and better wound alignment (Langley et al., 2006; Metcalfe et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007).

- Results in no difference in reported postnatal pain, but analgesia use is increased (Langley et al., 2006; Leeman et al., 2007).

- Most women find suturing unpleasant, uncomfortable and painful (Saunders et al., 2002). Women may feel they are ‘being patched up’ but endure it because they believe it to be beneficial (NICE, 2007).

All women should be aware that suturing remains strongly advisable for extensive perineal trauma, a large second-degree tear, a third- or fourth-degree tear, if bleeding continues, if the wound is very misaligned/complicated or the result of an unnatural straight-edged cut from an episiotomy. Ultimately, it must remain the woman’s choice whether to accept or decline suturing.

Third- and fourth-degree tears

Bedwell (2006) found that a midwife may be stigmatised and overtly or covertly criticised if a third- or fourth-degree tear follows a normal birth. Bedwell’s analysis of the evidence found that third-degree tears were not associated with the delivery technique nor were they preventable and that although midwives often felt personally responsible, and even guilty, they should be reassured that such tears remain the unavoidable outcome for a tiny percentage of births.

Failure to diagnose third- or fourth-degree tears may be considered substandard care and this contributes to most litigation associated with perineal trauma (RCOG, 2004). Such tears should be properly assessed and sutured by an experienced doctor in theatre, usually under regional anaesthesia. Post-repair care usually involves a catheter, stool softeners and antibiotics (RCOG, 2004).

Due to the impact such trauma can have on a woman’s quality of life, the woman should receive clear explanations and obstetric follow-up (Sultan, 2002). The community midwife and general practitioner should also be informed. Webb et al. (2007) suggest:

‘There is no prescribed mode of delivery for any subsequent birth: this will need to be an individualised decision made nearer the time, based on a number of factors including bladder and bowel function and what the woman wishes.’

Providing care for survivors of childhood sexual abuse

Women may not disclose that they have been sexually assaulted as a child or adult. Symptoms exhibited by abuse survivors can be misinterpreted and result in women being labelled as ‘difficult patients’. This lack of awareness can result in inappropriate treatment, causing further psychological trauma (Aldcroft, 2001).

For some women the restriction of the lithotomy position makes them feel they are at the mercy of an authoritative figure and are submitting to a painful, invasive and sexually threatening procedure. This can leave them feeling violated and powerless (Kitzinger, 1992) and can have far-reaching psychological consequences. It may affect the relationship with the baby who may inadvertently be blamed for ‘putting them through this’ (Aldcroft, 2001). (For more information see Chapter 2.)

Suturing procedure

Long-term physical, psychological and social problems may result from incorrect approximation of wounds and unrecognised trauma to the external anal sphincter (RCOG, 2004). The three main factors that influence the outcome of perineal repair are the suturing material, the repair technique and the skill of the operator (RCOG, 2004).

Analgesia

Saunders et al. (2002) reported women’s experience of pain during perineal suturing: 17% of women reported ‘distressing’, ‘horrible’ or ‘excruciating’ pain. To the reviewers’ surprise, women’s pain scores did not diminish as the time between suturing and pain reporting increased. In particular, women without regional anaesthetic were found to endure high levels of pain during this procedure. The clinician must be gentle, sensitive and never proceed if the woman is inadequately anaesthetised.

- Women may combine entonox and local or regional anaesthetic.

- If the woman has an epidural in situ, the midwife should readily offer a ‘top-up’ as Saunders et al. (2002) found that this offers a superior degree of analgesia compared to local anaesthetic.

- Local anaesthetic takes time to work effectively; the clinician can inject up to 20 ml of 1% Lidocaine/Lignocaine™ (NICE, 2007) and leave it to work prior to preparing equipment for the procedure.

- Take care to avoid intravascular injection of Lidocaine/Lignocaine by drawing back on the syringe plunger, to ensure no blood is aspirated which might indicate a vessel has been penetrated. Injection into a blood vessel can cause central nervous system excitatory response leading to confusion, convulsions, respiratory depression, bradycardia and even death (JFC, 2007).

Suturing materials

Current evidence suggests that the suture material of choice for perineal repair is rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 (Vicryl™) and a good second choice is polyglycolic acid as these synthetic sutures are associated with less perineal pain, analgesic use, dehiscence and resuturing, but increased suture removal, when compared with catgut. Catgut suture material has been withdrawn from the UK market since 2002 (RCOG, 2004; Kettle & Johanson, 2006a).

Suturing techniques

Suturing is an aseptic technique. The type of tear may involve different layers (see also Table 4.1) and so will influence the type of suturing technique:

- Muscle layer. Current evidence supports using a loose, continuous non-locking technique to suture vaginal tissue and perineal muscle. Subsequent stitch tightness and tension from reactionary oedema are transferred more evenly throughout the whole length of the single knotless suture, which is thought beneficial in reducing short-term pain and subsequent suture removal for tightness and discomfort (Kettle et al., 2002; RCOG, 2004) (See under ‘Perineal suturing procedure’).

- Skin layer. The use of subcuticular continuous suturing is superior to interrupted sutures for the perineal skin (Kettle et al., 2002; Kettle & Johanson, 2006b). All midwives should learn and practice this simple technique as it reduces postnatal pain and constitutes best practice.

- Skin layer unsutured. Studies have also evaluated suturing only the vaginal and perineal muscle layers but leaving the skin unsutured. NICE (2007) suggests if the edges are opposed, the perineal skin can remain unsutured. This is also preferable to interrupted sutures to the skin, resulting in a significant reduction in adverse outcomes, but was associated with a slight increase in wound gaping up to 10 days following birth (RCOG, 2004). Petrou et al. (2001) suggest leaving the skin unsutured is also cost-effective as it reduces use of healthcare resources.

There has, as yet, been no comparison between subcuticular continuous suturing and leaving the skin unsutured.

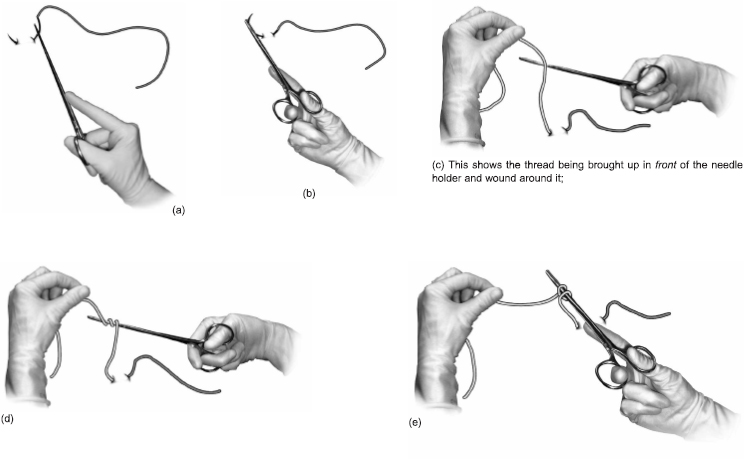

Figure 4.1 shows the basic sequence of inserting a stitch and tying a knot.

Suturing at home

Midwives must be resourceful! A good fixed light source is essential. Ensure the woman can lie comfortably with her bottom on the edge of a firm bed with the midwife positioned on the floor or low stool. The woman may find it most comfortable to rest her legs on separate chairs or she can abduct them herself but this is only usually comfortable for a short time. If both the woman and the midwife get on the floor, it is very hard on the midwife’s back and visualising/accessing the perineum can be awkward.

Perineal suturing procedure

Following discussion, explanations, reassurance and informed consent, the midwife can prepare everything ready for suturing, including a fixed light source, optional post-suturing analgesia and, in hospital, the call bell within reach (so the woman can summon assistance if required during suturing).

Before starting the repair address the following questions:

- Is the mother as comfortable as possible?

- Does she understand what has to be done and how long it will take?

- Can I see what has to be done?

- Can I do it?

Fig. 4.1 Suturing and tying a knot. (a)–(m) Illustrates the step-by-step insertion of a stitch and knot tying by a right-handed individual. Left-handed individuals can use an advanced photocopier to flip the images. Knots can be hand tied if preferred.