Introduction

‘Undisturbed birth… is the balance and involvement of an exquisitely complex and finely tuned orchestra of hormones’ (Buckley, 2004a).

The most exciting activity of a midwife is assisting a woman in labour. The care and support of a midwife may well have a direct result on a woman’s ability to labour and birth her baby. Every woman and each birthing experience is unique.

Many midwives manage excessive workloads and, particularly in hospitals, may be pressured by colleagues and policies into offering medicalised care. Yet the midwifery philosophy of helping women to work with their amazing bodies enables many women to have a safe pleasurable birth. Most good midwives find ways to provide good care, whatever the environment, and their example will be passed on to the colleagues and students with whom they work.

Some labours are inherently harder than others, despite all the best efforts of woman and midwife, and the midwife should be flexible and adaptable, accepting that it may be neither the midwife’s nor the mother’s fault if things do not go to plan. The aim is a healthy happy outcome, whatever the means.

This chapter aims to give an overview of the process of labour, but it is recognised that labour does not simplistically divide into distinct stages. It is a complex phenomenon of interdependent physical, hormonal and emotional changes, which can vary enormously between individual women. The limitation of the medical model undermines the importance of the midwife’s observation and interpretation of a woman’s behaviour.

Facts

- The National Service Framework recommends that women should have as normal a labour and birth as possible, and medical intervention should be used only when beneficial to mother and/or baby (Department of Health (DoH), 2004).

- Women should be offered the choice of birth at home, in a midwife-led unit or in an obstetric unit (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2007). An obstetric unit may be advised for women with certain problems, but it remains their choice.

- Women should be offered one-to-one care in labour (NICE, 2007). The presence of a caring and supportive caregiver has been proved to shorten labour, reduce intervention and improve neonatal outcomes (Green et al., 2000; Hodnett et al., 2004).

- Women tend to rate midwifery support as positive, although a few midwives are regarded as ‘off-hand’, ‘bossy’ or ‘unhelpful’ (Redshaw et al., 2007).

- A pleasurable labour can bring great joy but 5–6% mothers develop birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (Kitzinger & Kitzinger, 2007).

- The attitude of the caregiver seems to be the most powerful influence on women’s satisfaction in labour (NICE, 2007).

Signs that precede labour

Women often describe feeling restless and strange prior to going into labour, sometimes experiencing spurts of energy or undertaking ‘nesting’ activities (Burvill, 2002). Physical symptoms of prelabour may include:

- low backache and deep pelvic discomfort as the baby descends into the pelvis;

- upset stomach/diarrhoea;

- intermittent episodes of regular tightening for days or weeks prior to birth;

- loss of operculum (‘show’) usually clear or lightly bloodstained;

- increased vaginal leaking or ‘cervical weep’; and

spontaneous rupture of membranes (ROM) – usually unmistakeable, but sometimes less so, particularly if the head is well engaged (see Boxes 1.1 and 1.2 for diagnosis and management of ROM).

- This is usually conclusive in itself (Walsh, 2001a).

- Clarify the time of loss and the appearance and approximate amount of fluid.

- The pad is usually soaked: if no liquor evident, ask the woman to walk around for an hour and check again.

- Liquor may be:

Clear, straw-coloured or pink: it should smell fresh.

Clear, straw-coloured or pink: it should smell fresh. Bloodstained: if mucoid contamination, this is probably a show – but perform CTG if you doubt this (NICE, 2007).

Bloodstained: if mucoid contamination, this is probably a show – but perform CTG if you doubt this (NICE, 2007). Offensive smelling: this may indicate infection.

Offensive smelling: this may indicate infection. Meconium-stained (green): a term baby may simply have passed meconium naturally, but always pay close attention to meconium. Light staining is less of a concern, but dark green or black colouring and/or thick and tenacious meconium means It Is fresh, and this could be more serious. NICE (2007) advises continuous EFM for significant meconium and ‘consider’ continuous EFM for light staining, depending on the stage of labour, any other risks, volume of liquor and FHR.

Meconium-stained (green): a term baby may simply have passed meconium naturally, but always pay close attention to meconium. Light staining is less of a concern, but dark green or black colouring and/or thick and tenacious meconium means It Is fresh, and this could be more serious. NICE (2007) advises continuous EFM for significant meconium and ‘consider’ continuous EFM for light staining, depending on the stage of labour, any other risks, volume of liquor and FHR.- If the history is unmistakable or the woman is in labour, there is no need for a speculum examination.

- Never perform a vaginal examination unless the woman is having regular strong contractions and there is a good reason to do so: it risks ascending infection.

- To perform:

Suggest that the woman lies down for a while to allow liquor to pool.

Suggest that the woman lies down for a while to allow liquor to pool. Lubricate the speculum and gently insert it: the mother may find that raising her bottom (on her fists or a pillow) allows easier and more comfortable access.

Lubricate the speculum and gently insert it: the mother may find that raising her bottom (on her fists or a pillow) allows easier and more comfortable access. If no liquor visible, ask her to cough: liquor may then trickle through the cervix and collect in the speculum bill.

If no liquor visible, ask her to cough: liquor may then trickle through the cervix and collect in the speculum bill. Amnisticks (nitrazine test) are no longer recommended due to high false positive rates.

Amnisticks (nitrazine test) are no longer recommended due to high false positive rates.- Suggest that the woman avoids sexual intercourse or putting anything into her vagina.

- Suggest that she wipes from front to back after having her bowels opened.

- Inform her that bathing or showering is not associated with any increase in infection.

- Advise her to report any reduced fetal movements, uterine tenderness, pyrexia or feverish symptoms.

- Ask her to come back after 24 hours if labour has not started.

- Tell her that 60% women go into labour within 24 hours. If no labour within 24 h (NICE, 2007)

- NICE advises induction of labour after 24 hours of PROM (see Chapter 18). The woman will then be advised to remain in hospital for 12 hours afterwards so that the baby can be observed.

- If a woman chooses to wait longer, continue as above and review every 24 hours.

- After birth observe asymptomatic babies (PROM >24 hours) for 12 hours: at 1 hour, 2 hours and then 2-hourly for 10 hours: observe general well-being, chest movements and nasal flare, colour, tone, feeding temperature, heart rate and respiration. Ask the mother to report any concerns.

Not all women seek advice at this stage. For those who do, the midwife should act as a listener and reassure the woman that these prelabour signs are normal. Avoid using negative terms such as ‘false labour’.

First stage of labour

Latent stage

Characteristics of latent stage

NICE (2007) describes this as:

‘… a period of time, not necessarily continuous, when:

- there are painful contractions, and

- there is some cervical change, including cervical effacement and dilatation up to 4 cm’

Midwifery care in latent phase

Women may be excited and/or anxious. They will need a warm response and explicit information about what is happening to them. In very early labour they may need just verbal reassurance; they may make several phone calls.

While not offered everywhere, home assessment is preferable to hospital; it reduces analgesia use, labour augmentation and caesarean section (CS) and is therefore probably also cost-effective. Women report greater feelings of control and an improved birth experience (McNiven et al., 1998; Walsh, 2000a; Lauzon & Hodnett, 2002).

Some women experience a prolonged latent phase, which may be tiring and demoralising, requiring more support (see section ‘Prolonged latent phase’, Chapter 8). These women may undergo repeated visits/assessments and feel that something is going wrong. Most women however cope well.

- Always greet a woman warmly and make her feel special.

- Observe, listen and acknowledge her excitement. Her first contact with a midwife is important as it will establish trust.

- Be positive but realistic: many women, especially primigravidae, are overoptimistic about progress.

- Women whose first language is not English may need extra reassurance, careful explanations and sensitivity to personal and cultural preferences. A translator that the woman is comfortable with should have been arranged prior to labour, but this is sometimes not the case.

- If labour is not established, gently explain that she is not in strong labour yet and, if it is night time, suggest she attempts to go back to sleep, or at least tries to rest. During the day she should try to relax, try warm baths or distractions such as shopping, walking or watching a film.

- If the woman has sougth direct contact, then if all is well she should be left at home, or discharged home if in hospital, to establish in labour.

- Encourage her to eat and drink at not to focus on labour and coping techniques too early; instead she should try to get on with everyday life (Simkin &Ancheta, 2005).

Table 1.1 Baseline observations in labour.

| Observation | Frequency | Significance |

| Blood pressure | Tested at labour onset and then hourly (NICE, 2007) | Hypertension can be caused by: |

| Normal range: | • Anxiety and pain | |

| Systolic: 100–140 mm Hg | • General anaesthesia | |

| Diastolic: 60–90 mm Hg | Pre-eclampsia | |

| (Baston, 2001) | Pre-eclampsia is defined as: | |

| • Diastolic BP≥ 90 mm Hg on two or more occasions at least 4 hours apart | ||

| • Diastolic BP ≥ 110 mm Hg on one occasion | ||

| • Systolic >160 mm Hg or diastolic ≥110 mm Hg or a mean arterial pressure >125 mm Hg | ||

| • BP ≥140/90 mm Hg with proteinuria (≥2+) (see Chapter 19) | ||

| Hypotension can be caused by: | ||

| • An epidural/top-up | ||

| • Aortocaval occlusion secondary to lying supine | ||

| • Haemorrhage and hypovolaemic shock (see Chapter 15) | ||

| Pulse rate Normal range: 55–90 beats/min | Tested at labour onset and then hourly when checking the fetal heart (NICE, 2007) | Tachycardia ≥100 bpm can be caused by (Baston, 2001): |

| • Anxiety, pain, hyperventilation | ||

| • Dehydration, pyrexia | ||

| • Exertion | ||

| • Obstructed labour | ||

| • Haemorrhage, anaemia and shock | ||

| Bradycardia ≤55 bpm can be caused by: | ||

| • Rest and relaxation | ||

| • Injury and shock | ||

| • Myocardial infarction | ||

| Temperature Normally 36.37°.C | Tested at labour onset and then 4-hourly (NICE, 2007) or hourly if in birthing pool | Pyrexia >37.C can be caused by: |

| • Infection | ||

| • Epidural – usually low-grade pyrexia but rises with time | ||

| • Dehydration | ||

| • Overheated birth pool (see Chapter 7) |

- The physical check includes the following:

Baseline observations. Blood pressure (BP), pulse and temperature (see Table 1.1).

Baseline observations. Blood pressure (BP), pulse and temperature (see Table 1.1). Urinalysis. Testing a sample at labour onset is recommended by NICE (2007), although its helpfulness in a normotensive woman is debatable since vaginal secretions, e.g. liquor, often contaminate the sample and abnormal findings are often ignored.

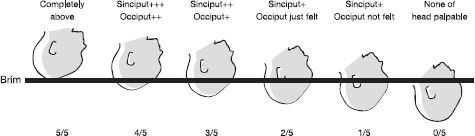

Urinalysis. Testing a sample at labour onset is recommended by NICE (2007), although its helpfulness in a normotensive woman is debatable since vaginal secretions, e.g. liquor, often contaminate the sample and abnormal findings are often ignored. Abdominal palpation. Ascertain fundal height, lie, presentation, position and engagement (see Fig. 1.1). Ask about fetal movements.

Abdominal palpation. Ascertain fundal height, lie, presentation, position and engagement (see Fig. 1.1). Ask about fetal movements. Fetal heart (FH) auscultation. Low-risk women should be offered intermittent auscultation. There is no place for a ‘routine admission trace’ for low-risk women (NICE, 2007) (see Chapter 3 for more detail).

Fetal heart (FH) auscultation. Low-risk women should be offered intermittent auscultation. There is no place for a ‘routine admission trace’ for low-risk women (NICE, 2007) (see Chapter 3 for more detail).Fig. 1.1 Engagement of fetal head (fifths palpable).

- Vaginal examination (VE) is not usually warranted if contractions are <5 min apart and lasting >60 seconds unless the woman really wants one.

- Ruptured membranes (see Box 1.1 for diagnosis) are usually obvious. If the woman is contracting, there is no need to do anything other than note the history and observe the liquor. Do not perform a VE unless the woman really wants one and she is contracting strongly and regularly, due to risk of infection.

Prelabour rupture of the membranes at term

Some women experience prelabour rupture of the membranes (PROM) at term. There are some risks, including infection, cord prolapse and sometimes the iatrogenic consequences of intervention. However, most women with PROM will go into labour spontaneously and have a good outcome. For management seeBox 1.2. Refer to Chapter 18 for more information.

Established first stage of labour

Characteristics of the established first stage

In early labour:

- The woman may eat, laugh and talk between contractions.

- Contractions become stronger and increasingly painful, 2–5 minutes apart lasting ≤60 seconds.

- The cervix is mid to anterior, soft, effaced (not always fully effaced in multiparous women) and >4 cm dilated.

As labour advances:

- The woman usually becomes quieter, behaves more instinctively, withdrawing as the primitive parts of the brain take over (Ockenden, 2001).

- During contractions she may become less mobile, holding someone/something during a contraction or stand legs astride and rock her hips. She may close her eyes and breathe heavily and rhythmically (Burvill, 2002), moaning or calling out during the most painful contractions.

- Talking may be brief, e.g. ‘water’ or ‘back’. This is not the time for others to chat. Lemay (2000) echoes Dr Michel Odent’s constant advice in advising midwives: ‘the most important thing is do not disturb the birthing woman’. Midwives are usually adept at reading cues. Others unfamiliar with labour behaviour, including her partner and students, may need guidance to avoid disturbing her, particularly during a contraction. Before auscultating the FH, first speak in a quiet voice or touch the woman’s arm; do not always expect an answer.

Midwifery care in established first stage

The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) Campaign for Normal Birth (available at: www.rcmnormalbirth.org.uk) has produced eight top tips to enhance women’s birth experience. These are listed over the page in Box 1.3

- Make sure your manner is warm. Involve her partner. Clarify how they prefer to be addressed. Ideally, the woman will have already met her midwife antenatally. However this is not always possible. A good midwife, familiar or not, will quickly establish a good rapport. Kind words, a constant presence and appropriate touch are proven powerful analgesics.

- Take a clear history. Discuss previous pregnancies, labours and births: how does the woman feel about these? Ask about vaginal loss, ‘show’, time of onset of tightenings. Look for relevant risk factors.

- Review the notes. Check any ultrasound scans for placental location and dating or size estimation. Ensure you have a blood group and recent haemoglobin result. Check any allergies.

- Offer continuous support. Cochrane review (Hodnett et al., 2004) found that continuous support in labour:

reduces use of pharmacological analgesia including epidural;

reduces use of pharmacological analgesia including epidural; makes a spontaneous birth more likely, with fewer instrumental deliveries and caesarean sections;

makes a spontaneous birth more likely, with fewer instrumental deliveries and caesarean sections; shortens labour; and

shortens labour; and increases women’s satisfaction with labour

increases women’s satisfaction with labourSupporting a woman and her partner in labour is an intense relationship, hour after hour, and can be physically and mentally demanding. Providing emotional support, monitoring labour and documenting care may mean that the midwife can hardly leave the woman’s side. Involving the birth partner(s) or a doula can both support the midwife and enhance the quality of support the woman receives. There should be no restriction on the number of birth partners present, although be very sure that they are the people the mother really wants. Sometimes women accede to the desires of sisters or friends to be at the birth. Birth however is not a spectator sport: if they are chatting amongst themselves and not supporting the woman then the midwife may need to offer them some direction or tactfully suggest they leave the room.

- “Listen to her” (RCM, 2005). Talk through any birth plans early, while the woman is still able to concentrate. As labour progresses, observe her verbal and body language and tell her how well she is coping, offering simple clear information. Try not to leave her alone unless she wishes this.

- “Build her a nest” (RCM, 2005). In order to make the birth environment welcoming prepare the room before she arrives.

Mammals like warm dark places to nest, so keep it relaxed with low lighting.

Mammals like warm dark places to nest, so keep it relaxed with low lighting. Remove unnecessary monitors/equipment.

Remove unnecessary monitors/equipment. Noise, particularly other women giving birth, can be distressing; low music may help cut out such noise. Avoid placing a woman arriving in labour adjoining someone who is noisy.

Noise, particularly other women giving birth, can be distressing; low music may help cut out such noise. Avoid placing a woman arriving in labour adjoining someone who is noisy. Keep interruptions to a minimum; always knock before entering a room and do not accept anyone else failing to do this.

Keep interruptions to a minimum; always knock before entering a room and do not accept anyone else failing to do this. If there is a bed in the room, consider pushing it to the side so that it is not the centrepiece (National Childbirth Trust (NCT), 2003).

If there is a bed in the room, consider pushing it to the side so that it is not the centrepiece (National Childbirth Trust (NCT), 2003).RCM (2005).

- Eating and drinking. Women often want to eat in early (rarely later) labour. Offer her what she feels like, e.g. high-calorie snacks, fruit juice, tea, toast, cereal and biscuits (Johnson et al., 2000). Drinking well will prevent dehydration, and a light diet is appropriate unless the woman has recently had opioids or is at higher risk of a general anaesthetic (NICE, 2007). Ensure her birth attendants eat too.

- Basic observations (see Table 1.1). There is a lack of evidence supporting many routine labour observations (Crowther et al., 2000; NICE, 2007), but NICE (2007) recommends hourly pulse (checked simultaneously with the fetal heart rate (FHR)) and BP, 4-hourly temperature. Consider hourly temperature if water birth (see Chapter 7).

- Frequent micturition. It should be encouraged, but urinalysis in labour is probably pointless. NICE (2007) recommends testing one sample at the onset of labour but the benefit is unclear as vaginal secretions and liquor commonly contaminate the sample and ‘abnormal findings’ are often, in practice, ignored.

- Observe vaginal loss discreetly, e.g. liquor, meconium, blood and offensive smell.

- FH auscultation: NICE (2007) recommends every 15 min for 1 min following a contraction. Midwives may disagree with this guidance that is based on consensus opinion rather than clear evidence of benefit and may choose to monitor less than every 15 min early in labour or, more frequently, at other times, e.g. following spontaneous rupture of the membranes or a VE. For more information see Chapter 3.

Assessing progress in labour

‘… Justify intervention’ (RCM, 2005).

Unless birth is imminent, most midwives undertake abdominal palpation when taking on a woman’s care and, periodically thereafter, to ascertain the lie, position and presentation of the baby. Engagement is particularly helpful to monitor descent of the presenting part and thus labour progress (see Fig. 1.1). However some women may find this examination painful, particularly in advanced labour.

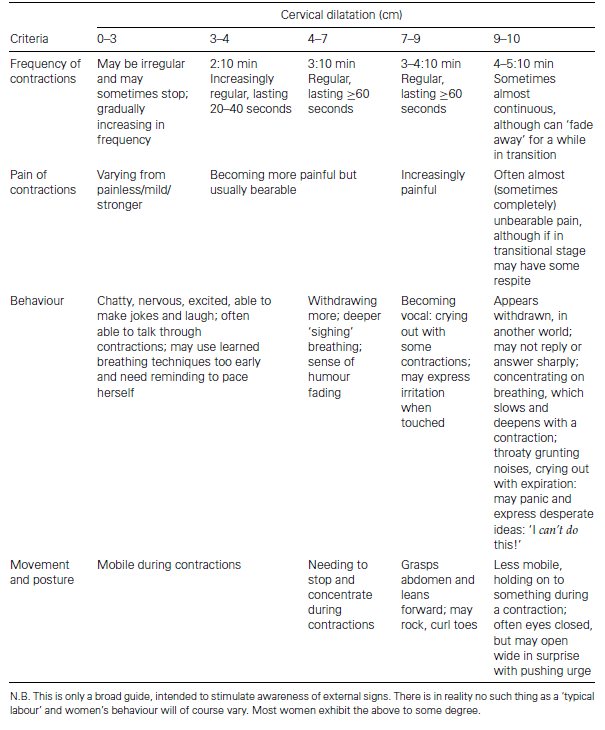

The assessment of progress can also be judged observationally: by the woman’s contractions and her verbal and non-verbal response to them (Stuart, 2000; Burvill, 2002; see Table 1.2 ). Some midwives also observe the ‘purple line’, which may gradually extend from the anal margin up to the nape of the buttocks by full dilatation (Hobbs, 1998).

Vaginal examination and artificial rupture of the membranes

VEs in labour are an invasive, subjective intervention of unproven benefit (Crowther et al., 2000). However, they do remain the accepted method for assessing the progress of labour (see Chapter 2).

It can be difficult for woman to decline a VE or for the midwife to choose to perform one more selectively (i.e. when she/he feels one is best indicated). Even in low-risk births, midwives often feel pressured to adhere to guidelines which lack good evidence and have a medical bias.

NICE (2007) recommends the following:

- Four-hourly VEs in the first stage of labour.

- Cervical dilatation of 0.5 cm/hour as reasonable progress (Crowther et al., 2000; NICE, 2007).

Table 1.2 Contractions and women’s typical behaviour.

- A 4-hour rather than 2-hour action line on the partogram. This appears to reduce intervention for primigravidae with no adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes (Lavender et al., 2006; NICE, 2007).

- In normally progressing labour, amniotomy should not be performed routinely (NICE, 2007). The decision should only be made in consultation with the woman, when the evidence is discussed and the intervention justified and not minimised (RCM, 2005) (see also Chapter 2 for more on ARM).(For more on partograms and assessing progress see Chapter 8.)

Fig. 1.2 Hands on comfort: massage and touch.

- Document all care on the partogram and in the notes, including any problems, interventions or referrals (for more on record keeping see Chapter 22).

Analgesia

Most midwives encourage natural and non-interventionist methods first, with pharmacological methods only if these methods are deemed insufficient. Pain is a complex phenomenon and a pain-free labour will not necessarily be more satisfying; working with women’s pain rather than alleviating it underpins many midwives’ practice (Downe, 2004).

The following is a brief overview.

Non-pharmacological analgesia

- Massage and touch. These can be powerful analgesics (Fig. 1.2), e.g. back rubbing, breathing and relaxation, massage and touch. These encourage pain-relieving endorphin release. Never underestimate the effect of being ‘with woman’.

- Distraction, e.g. breathing patterns, music and television.

- Position changes with aids. These include beanbags, wedges, stools and birthing balls (e.g. Figs. 1.3 and Fig 1.4).

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Despite conflicting opinions on effectiveness of TENS, including possible placebo effect, many women report that it provides good pain relief, especially in the first stage of labour (Johnson, 1997). There is no adverse effect on the mother or baby (Mainstone, 2004). However lack of substantial non-anecdotal evidence has led NICE (2007) to conclude, very controversially, that TENS should not be recommended in established labour.

Fig. 1.3 Kneeling forwards onto a pillow.

- Aromatherapy. Only oils known to be safe in pregnancy should be used: some are contraindicated in pregnancy (Tiran, 2000). Continuous vaporisation may impede concentration and have adverse maternal effects (Tiran, 2006). Oils should be diluted, preferably to half the usual dilution in pregnancy. For a bath, adding the drops to milk prior to putting them in water helps them disperse.

- Other methods, e.g. acupuncture/pressure, reflexology, shiatsu, yoga, hypnosis (including self-hypnosis), homeopathic and herbal remedies. Normally only midwives trained in these specialist areas or qualified practitioners offer these therapies. Non-pharmacological methods are notoriously difficult to evaluate by standard research methods. Acupuncture and hypnosis are the only complementary therapies that have been clinically proved to work (Smith et al., 2006; NICE, 2007).

- Water. Deep-water immersion has unique benefits (see Chapter 7). The opportunity to labour in water should be more widely adopted as part of routine care and is recommended by NICE (2007).

Pharmacological analgesia

- Entonox (nitrous oxide). This is possibly the most commonly used labour analgesic in the UK. There is little evidence on the effects of entonox on a mother or baby, and it is usually assumed that it is fairly safe. There are minor side effects, e.g. dry mouth or nausea, but entonox is quickly excreted from the woman’s system and so the effects wear off rapidly if the woman stops using it. Long-term exposure risks are well documented, including the risk to pregnant staff with high labour ward workloads (Robertson, 2006).

Fig. 1.4 Side lying.