Healthcare Teams

The previous chapter deals with the healthcare professionals who are found in healthcare teams. Now we turn to the person at the center of each team, namely, the patient. Patients sometimes are referred to as clients by some healthcare professionals, especially social workers. By using the word patient we do not mean to suggest any disagreement with those who prefer to use the word client. Specifically, we do not mean to imply that all patients are or should be passive or dependent. Of course, sometimes patients are dependent—for example, when they are acutely ill and cannot think and act normally, say, because of severe chest pain or the effects of a life-threatening infection. But these examples of dependency are unusual. Most of the time patients are fully capable of making decisions about their care. Nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and most other healthcare professionals ordinarily use the word patient when referring to a person who is receiving health care. Since these professionals comprise most of the readership for this book, we use the word patient too.

Others may refer to patients as consumers or customers. If we were thinking of people who are choosing health insurance or choosing which clinic to select for care—especially if they have no immediate need for health care—these terms might be appropriate. But this is a book for people who are providing care, not a book for people who are marketing or selling health insurance or health services. We have more to say about consumers and consumerism below.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine, 2001). This book changed how the quality of health care is conceptualized in the healthcare professions in the United States. Echoes from its pages are still heard today and probably will continue to be heard for many more years. Among other innovations, the IOM report provided a functional definition of quality that has become the standard starting point for endeavors to measure healthcare quality and improve it.

Prior to the publication of Crossing the Quality Chasm, the most commonly quoted definition of quality in health care came from an IOM report issued 11 years earlier. That report defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Institute of Medicine, 1990, p. 21). While the 1990 definition was an improvement on earlier definitions and served its purposes, in hindsight the definition is remarkable for what it leaves out, namely, any reference to patients and to the goals that patients have in seeking health care. The 1990 definition is crafted from the viewpoint of healthcare professionals. It implies, without directly stating so, that defining healthcare quality is a task appropriate for individuals who can judge whether health services “are consistent with professional knowledge” and that their proper central concern is whether health services achieve “desired health outcomes.” In other words, the assumed touchstone for quality is whether health care cures disease or, if cure is not possible, alleviates symptoms. There is no mention of how patients experience their care, whether they receive comfort and emotional support, whether their questions are answered, or whether they play any role in the process of care.

The definition offered in Crossing the Quality Chasm in 2001 was not a refinement of the earlier definition. The newer definition represented a major shift in understanding the elements of good health care (Berwick, 2009). The 2001 report framed its definition in terms of 6 aims for the improvement of care, stating that “health care should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable” (IOM, 2001, p. 40). There are 4 new elements in this definition as contrasted with the 1990 definition. Safety and effectiveness are implied by the earlier definition, but patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity are all new. Although all of these aims are important, the purpose of this chapter is to explain the role of the patient in healthcare teams; and so we focus on the concept of patient-centeredness. The other 5 aims are discussed in Chapter 6.

In advocating that care be patient-centered, the authors of Crossing the Quality Chasm might have meant that care should be more tightly focused on treating diseases as they appear in different forms or presentations in particular individuals. In that case, the IOM definition would have continued the professional orientation of the 1990 definition. However, it is clear that the authors of the report meant to propose a different and much broader notion of patient-centeredness. The report highlighted the need to eliminate patients’ frustrations with being blocked from participating in decision making and their frustrations in obtaining information about their own situations and about health care generally (IOM, 2001, pp. 48-51). The report also called for “respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs.” In other words, patient-centeredness means satisfying not only patients’ needs, which might be determined by the professionals using their views of what is needed, but also patients’ wants, which can be known only if patients state what their wants are or are asked about them (Berwick, 2009, pp. w558-w559). Alternatively, one could say that patient-centeredness means fashioning care so that it serves the patients’ interests as defined by them, not by the professionals who provide their health care.

The essence of patient-centered care is recognition of the autonomy, dignity, sensibility, and self-awareness of the individual patient. It stands in contrast to what is usually called paternalistic care, in which patients are regarded essentially as children who do not have the ability or the right to make good decisions about their own health care. It also stands in contrast to a degraded form of paternalism in which the thoughts and feelings of patients are neglected and patients are treated essentially as mammals in need of repair.

Although Crossing the Quality Chasm brought patient-centeredness to the forefront of discussions about healthcare quality, it actually has a history of many decades. An early expression of this value in the United States came from William J. Mayo, co-founder of Mayo Clinic, who said in a 1910 medical school commencement address, “The best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered” (Mayo, 2000, p. 554). Dr. Mayo’s statement is not entirely unambiguous in that he does not say who is expected to determine the patient’s interest. It is possible that he meant for the patient’s interest to be determined by the physician, who has special knowledge that the patient does not have. But even if this was his meaning, his statement foreshadowed the future by asserting that the proper aim of health care is advancing the patient’s interest instead of making best use of professional knowledge. As the 20th century progressed, the role of science in health care expanded, and medicine placed increasing emphasis on identifying and repairing defects in human bodies seen as biological machines. By about 1950, a growing number of nurses, physicians, and others began to confront the limitations of health care conceived primarily as biological investigation and repair. The term patient-centered approach first appeared in the nursing literature about 1960 (Martin, 1960). In Britain, Michael Balint, a physician and psychoanalyst, created study groups in which general practitioners could improve their abilities to understand their patients’ experiences of illness and medical care (Balint, 1964). In the United States, George Engel, an internist and psychiatrist, promoted medical practice that integrates knowledge of a patient’s physiological function with an understanding of the patient’s psychological and social life (Engel, 1977). Later, Susan Edgman-Levitan and her colleagues in the Picker/Commonwealth Program for Patient-Centered Care developed the concept of patient-centeredness and devised criteria for measuring whether care is patient-centered (Gerteis et al, 1993). Similar inquiries led to the development of narrative medicine, which emphasizes the value of understanding the patient’s story of his or her illness, including his or her experience of health care (Greenhalgh and Hurwitz, 1999). Over the past 35 years, Moira Stewart and others, located mainly in Canada, have developed the patient-centered clinical method, which emphasizes understanding the patient’s experience of illness, life history, and social context as the basis for finding common ground on which the clinician and patient establish goals for working together to improve the patient’s health (Stewart et al, 2003). Patient-centered care has remained an important concept in nursing education and nursing practice in the decades since discussion of the concept first appeared in print in 1960. Alleviating vulnerability, whether physiological or psychological, has been a central component of the concept as it has been interpreted in nursing (Hobbs, 2009). The people mentioned here and many others have contributed to changing the focus of clinical care from repairing the machine to regarding the whole person with respect as an autonomous, dignified human being.

The authors of Crossing the Quality Chasm drew on all of these developments. They did, however, also add something new and important. Patient-centered medicine, narrative medicine, and the other approaches noted above are all concerned with improving the way that individual clinicians go about doing their work in diagnosing and caring for one patient at a time. In these approaches, patient-centeredness, whether or not this term is used explicitly, is conceived as a property of individual clinical practice. In Crossing the Quality Chasm, patient-centeredness is presented not only as a characteristic of the work of individual healthcare professionals but also as a characteristic of the operations of health systems. In other words, the authors of the IOM report urged whole healthcare institutions to be patient-centered. This broadening of the concept leads immediately to questions about teamwork in institutions, the physical appearance and function of healthcare facilities, billing procedures, reward systems for employees of hospitals, and so on. Expanded in this way, patient-centeredness brings together systems thinking and the concept of the patient as person (instead of the patient as biological machine). This combination sets the stage for understanding how patients can and should participate in healthcare teams—if they choose to do so.

CONSUMERISM

We noted earlier that some individuals refer to patients as consumers. Many clinicians, especially physicians, bristle at the notion of patient-centeredness because they think it signals consumerism insinuating itself into health care. Some object because they do not believe that patients should be in charge. We offer no defense for that viewpoint. Other clinicians object even though they do believe that patients should be in charge if they want to be.

Does the IOM concept of patient-centeredness imply that patients should be regarded as consumers? Maybe. It depends on what the word consumer is taken to imply.

If health care is to serve patients’ interests as defined by them, then the patients are in charge—just as someone buying a refrigerator or purchasing a lawn mowing service is in charge. If patients are in charge, they remain dependent on healthcare professionals for information about their diseases and treatment options, but they are no longer dependent on the professionals to make decisions about their care. Instead the dependency for decisions is reversed, and the professionals must take their cues from the patients. With this reversal, patients are no longer the passive recipients of health care deemed appropriate for them by the professionals. Patients decide what they will receive—and how and when. Evidently, they become consumers. As described in one influential book on doctor-patient communication, consumerism is one legitimate prototype for interactions between patients and healthcare professionals. (In that account, the other legitimate prototypes are paternalism and mutuality.) And consumerism has sweeping implications:

Caveat emptor, “let the buyer beware,” rules the transaction, with power resting in the buyer (patient) who can make the decision to buy (seek care) or not, as the patient sees fit. The physician’s role is limited to that of a technical consultant who has the obligation to provide information and services that are contingent on the patient’s preferences (and within professional norms). (Roter and Hall, 2006, p. 27)

But this line of reasoning overreaches. Labeling patients as consumers suggests that the relationships between a patient and those who provide his or her health care are commercial relationships. If patients and healthcare professionals relate to one another fundamentally as buyers and sellers, then apparently both the patients and the professionals may engage in frankly commercial behavior. For example, the seller apparently is permitted or even expected to exaggerate claims of effectiveness, contrive to hide ignorance, and stimulate demand artificially. Cautioning the buyer to beware implies that there is something to beware of, something that the healthcare professionals may deliberately not disclose. The warning caveat emptor makes sense only if misrepresentation and evasion are real possibilities—as they are in some commercial dealings.

Incidentally, Dr. Mayo would have been dismayed if he could have foreseen that in the 21st century patients might become consumers who need to beware. At the time of Dr. Mayo’s commencement address mentioned earlier, patients were emerging from a time when they did indeed need to beware. In his speech, he applauded the end of the pre-scientific era in medicine, when physicians had “stage properties,” “charlatanism,” and “commercial instincts” (Mayo, 2000).

Labeling patients as consumers also suggests that various limits on the behavior of patients no longer apply because the customer (or consumer) is always right and is not bound by evidence about the effectiveness of various treatments. Apparently, patients as consumers may request and receive treatments for which evidence of effectiveness is lacking and treatments for which there is evidence of ineffectiveness. Perhaps they will demand and receive treatments that are actually harmful. Perhaps they will demand unlimited time from physicians, nurses, and others. Perhaps they will, in general, behave like some demanding customers when they are buying television sets or airline tickets to Paris.

In fact, the writers of Crossing the Quality Chasm did not use the terms consumer or consumerism and did not intend to encourage a return of unrestrained commercialism in health care. Patient-centeredness does imply an end to unqualified professional authority. However, an end to unqualified authority does not mean the end of professionalism. A profession is not simply a conspiracy to maintain status and control. Members of a profession have responsibilities to put the interests of those whom they serve ahead of their own interests, to maintain their professional knowledge and skills, and to use their knowledge and skills with integrity—hiding nothing and being forthcoming and truthful in providing any information that is requested and any information that would be useful to those whom the professionals serve, even if those who are served do not know enough to ask for the information. Society has every reason to maintain these aspects of healthcare professionalism even though the patients have the last word. Patients do not expect or want to have commercial relationships with their nurses, physicians, and pharmacists. They want the professionals to remain professional. Conflating patients with consumers generates undesirable suggestions for professionals and for what patients can expect from professionals.

If labeling patients as consumers is meant to mark the principle that patients have final say in their own health care, well and good. However, if consumerism in health care were to mean that patients must beware because healthcare professionals are released from their obligations as professionals and have entered the commercial world, then both patients and society as a whole would be harmed. If consumerism were to mean that patients are now marketplace consumers, the consequences would also be undesirable. Patients then would no longer be expected to attend either to evidence about healthcare effectiveness or to the fact that ordinarily most of the costs are paid by someone other than the patients—a situation sharply different from that of real consumers. These understandable interpretations of consumerism, taken from our understanding of consumerism in other economic sectors and imported into health care, are both unwelcome and unnecessary. Moreover, they are unwanted by both patients and healthcare professionals.

In the end, the undesirable implications of consumerism in health care are probably the result of a simple confusion, invited by the word consumer. Perhaps we need a new term to label the relationship between patients-in-charge and healthcare professionals who retain professional obligations. Instead of consumerism, it could be called clientism. In any case, embracing patient-centeredness as an aim in health care does not require embracing consumerism as that concept is usually understood. A healthcare team that provides patient-centered care does not need to regard its patients as consumers. As Dr. Mayo said in 1921, “Commercialism in medicine never leads to true satisfaction, and to maintain our self-respect is more precious than gold” (Camilleri et al, 2005, p. 1341). The same could be said of commercialism among patients.

ENABLING PATIENTS TO PARTICIPATE IN DECISION MAKING

Patient-centeredness is a desirable feature of team-based health care, and the concept provides a touchstone or reference point for understanding the different roles that patients (and their families) can have in the decision making that occurs in healthcare teams. Patient-centered care raises both opportunities and problems that do not arise with paternalistic care, and these will be considered below. But let us first use the touchstone to differentiate 3 stories about patients participating in teams.

Asking Someone Else to Make Decisions

Asking Someone Else to Make Decisions

Adam Trudell was a 54-year-old writer and political activist, living in Rapid City, South Dakota. Mr. Trudell had a long history in literature and in politics, having published 4 novels and having served in the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs and in Congress. His education included a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in public administration. However, he had no education in the natural sciences beyond an introductory geology course in college.

Mr. Trudell had known for several years that he had heart disease, specifically, narrowed passages in the arteries supplying blood to his heart (coronary artery disease). His first symptom was chest pain that occurred while he was running. Once he began using medication, he was able to exercise again, but occasionally he still had chest pain with exertion.

One evening while eating dinner, Mr. Trudell experienced crushing chest pain that did not relent when he tried using nitroglycerin under his tongue. Mary Trudell, his wife, telephoned 911, and he was transported to the hospital. Linda Hill, RN, an emergency department (ED) nurse, greeted him, took a brief history, measured his blood pressure, and attached electrocardiographic monitor wires to his chest with small adhesive pads. James Dudik, MD, the ED physician, then took a longer history, did a physical examination, and ordered several tests. He then advised Mr. Trudell that he recommended immediate x-ray investigation of Mr. Trudell’s coronary arteries (angiography), to be followed by opening of any arterial blockage that might be found (angioplasty). Mr. Trudell asked 2 or 3 questions about what the procedure would involve. Dr. Dudik then asked Mr. Trudell whether he wished to go ahead with the procedure or be transferred to the Coronary Care Unit, where he would be treated without angiography or angioplasty.

Mr. Trudell paused for a moment, still in pain. He looked at Ms. Hill and then looked back to Dr. Dudik, but he said nothing. Then he asked Dr. Dudik to do as he thought best. Dr. Dudik asked whether he should explain the situation to Ms. Trudell and ask her to make the decision. Mr Trudell responded by repeating that he wanted Dr. Dudik to do as he thought best. A cardiologist was called, and Mr. Trudell was transferred to the catheterization laboratory for angiography.

At first glance, it might appear that Mr. Trudell’s care was paternalistic rather than patient-centered. Mr. Trudell behaved passively, and Dr. Dudik made the important decision about angiography. But passivity on the part of the patient does not by itself mean that the patient is receiving paternalistic care. Whether care is patient-centered depends on the attitude and behavior of the care giver or the healthcare team.

Mr. Trudell’s care was patient-centered because Dr. Dudik respected Mr. Trudell’s autonomy and dignity. Dr. Dudik began with the assumption that Mr. Trudell would make the decision about angiography. When Mr. Trudell said that he did not want to make the decision, Dr. Dudik again showed that he was treating Mr. Trudell as a person by asking him whether he wanted Ms. Trudell to serve as his agent in making the decision. The vignette does not make clear why Mr. Trudell declined to take this pathway. Perhaps he had good reason to think that his wife would also defer to Dr. Dudik. In any case, Mr. Trudell had every opportunity to be in charge. His thoughts, feelings, values, and goals were respected. He exercised his self-determination by choosing not to be the one to make an important decision about his care. This is one role open to patients as members of healthcare teams.

There is another issue to clarify here. Mr. Trudell was in pain when he made his decision not to make a decision about his care. Did he make that decision competently, or did Dr. Dudik do him a disservice by accepting his statement that he wanted Dr. Dudik to make the decision? This question often arises. Sometimes pain diminishes a patient’s capacity to think clearly and make a decision. Sometimes emotional turmoil interferes with clear thinking. Sometimes the patient has a decreased level of consciousness due to serious illness or injury. Clinicians must always be attentive to the possibility that the patient is not able to make a valid decision, and, if so, must engage a surrogate, usually a family member, to act on behalf of the patient when that is practical. In this case, Dr. Dudik might have tactfully insisted on engaging Ms. Trudell in the process if he believed that Mr. Trudell was sufficiently incapacitated. This could have taken the form of Dr. Dudik speaking separately with Ms. Trudell; but a gentler approach, more attentive to Mr. Trudell’s expressed wishes, would have been for Dr. Dudik simply to draw Ms. Trudell into the conversation that Dr. Dudik and Mr. Trudell were having. If a patient is not able to make decisions for herself or himself, making sure that the decisions are being made by a person who can truly speak for the patient—because that person knows the patient’s values and beliefs—is part of providing patient-centered care. Attending to the patient’s capacity for decision making is quite obviously appropriate when she or he is making decisions about what actions will be taken in the process of care, that is, what tests will be done and what treatments will be used. Attending to the patient’s ability to make decisions is also necessary when the patient is deciding what role she or he will have in the healthcare team.

Partnering on Decision Making

Partnering on Decision Making

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, highly variable disease, sometimes no more than a serious nuisance for people who have it, sometimes a serious disability for them. Many treatments are available. Some of the treatments have no significant side effects; some of them carry substantial risk.

Isabella Belmonte, age 62, was married with 2 adult children and 4 grandchildren. She worked as an executive assistant in a financial services firm in New York. For 30 years, she had had rheumatoid arthritis. The disease first affected her knees and later also affected her wrists and hands.

Ms. Belmonte received care for her arthritis from a rheumatologist whom she had been seeing for 16 years. She also had a family physician, but she had no significant health problems except for the arthritis, and so she saw her family physician only for preventive care and minor, short-term health problems.

Ms. Belmonte and Dr. Mancuso, her rheumatologist, had an excellent relationship. Ms. Belmonte had been referred to Dr. Mancuso by her family physician, who thought they would get along well. In fact, they got along magnificently. Ms. Belmonte felt that Dr. Mancuso understood her very well. He understood the central place of family in her life, the importance of her work to her, her need to maintain a good income to contribute to her family’s well-being, and her delight in interacting with her grandchildren.

Ms. Belmonte had been through many treatments for her arthritis over 30 years. She began with ibuprofen and later used steroids intermittently, both prescribed by her family physician. When these drugs no longer provided adequate relief, her family physician referred her to Dr. Mancuso for more aggressive treatment. Dr. Mancuso discussed with her the use of methotrexate, immunosuppressants, and other drugs, including the drugs’ prospects for success and their risks, for example, risk of liver damage and risk of infection. Together they decided whether she would use these more potent drugs. Over the years she had used 4 different drug combinations. Each time a change was made, she and Dr. Mancuso discussed what might lie ahead, how likely it was that an improvement would be achieved with the new regimen, and how her family and work lives might be disrupted if she experienced adverse effects of the drugs.

Dr. Mancuso practiced with 2 other rheumatologists. The office also included a clinical nurse specialist and a physical therapist. Ms. Belmonte had frequent interactions with both of them and learned a great deal from them about how to reduce her symptoms and cope with her disease.

Ms. Belmonte saw herself as a member of her healthcare team. In particular, she viewed herself and Dr. Mancuso as partners in managing her disease. She regarded their decision making about her treatment as shared decision making.

Ms. Belmonte received patient-centered care from Dr. Mancuso’s team, but her role in her own health care was quite different from the role chosen by Mr. Trudell in the earlier vignette. Ms. Belmonte’s choice for how she interacted with her care providers exemplifies a second option for the role of a patient in his or her healthcare team. She was not passive, but neither was she straightforwardly in charge. She did not want to be the supervisor of her own care; she wanted to be a partner. She did not regard Dr. Mancuso with suspicion. She did not think that he might be inclined to force her into treatments that he favored but that she might not want. She did not think that he might be exaggerating the effectiveness of new medications or minimizing the prospect of side effects. Ms. Belmonte did not think that she was a buyer who needed to beware, and Dr. Mancuso did not regard her as a consumer.

The question of who was in charge of her care never came up explicitly. From the questions she asked and from her responses to the various treatment options he discussed, Dr. Mancuso could see how Ms. Belmonte wanted to participate in her care. He found it easy to understand her values and goals in life. He presented treatment options that he thought were consistent with her values and likely to serve her goals. Sometimes they discussed her goals as part of making shared decisions. For example, at one point, they delayed beginning a new medication because of the chance that a side effect might prevent her from attending her granddaughter’s confirmation. During the delay, she continued to experience pain that was later relieved by the new medication without any side effects. But before she began taking the new medication, there was no way to know what might happen, and Ms. Belmonte did not want to risk missing the confirmation. This choice made sense to her and to Dr. Mancuso. Very little discussion was needed.

Ms. Belmonte felt understood and respected. She knew that her experience of her illness and her health care were important to Dr. Mancuso and to the nurse and the physical therapist in Dr. Mancuso’s office. Her questions were always answered as fully as she wished. She had no doubt that her values and goals governed the treatment choices that she made with Dr. Mancuso. The whole process worked very smoothly.

Making Decisions for One’s Self

Making Decisions for One’s Self

Dorothy Montgomery, age 36, was a high school teacher in St. Louis. She was married and had children aged 10 and 8. As was her custom roughly once a year, she saw Jane Bartnik, her gynecological nurse practitioner (NP) for a health check-up shortly before Thanksgiving. To Ms. Montgomery’s dismay, Ms. Bartnik found a lump in Ms. Montgomery’s left breast. A mammogram and several other tests were done, confirming the presence of a solid lump in the left breast, but there were no indications that there might be cancer elsewhere. Ms. Bartnik referred Ms. Montgomery to Wanda Richmond, MD, a surgeon in the same medical group. Dr. Richmond obtained tissue samples by inserting a needle through Ms. Montgomery’s skin into the lump (core needle biopsy). Examination of the tissue under a microscope revealed invasive ductal carcinoma, that is, breast cancer.

Even before the mammogram was done, Ms. Montgomery began gathering information about breast cancer. First, she spoke with 2 friends who had undergone treatment for breast cancer within the past few years. She then asked her NP for suggestions of websites and consulted several of them: the BJC HealthCare website, the National Cancer Institute website, and others.

After the biopsy showed that the lump was cancerous, Ms. Montgomery and her husband returned to Dr. Richmond to discuss treatment options. Ms. Montgomery was well aware that the breast cancer represented a threat to her life. She had many questions. Although she was agitated and sometimes had difficulty maintaining her concentration, for the most part she directed the conversation. At times her husband reminded her to ask questions that the 2 of them had discussed in advance. Dr. Richmond answered her first few questions in detail but then the answers became shorter, and eventually Dr. Richmond said that she thought Ms. Montgomery should have the lump removed along with lymph nodes from the armpit adjacent to the breast with the lump. The tumor tissue would then be tested, and further treatment would depend upon the results of the surgery and tests. Ms. Montgomery tried to ask some additional hypothetical questions about choices to be made once the results were known. She was already well informed about most of the tests and what they might show. Dr. Richmond indicated tactfully but firmly that she thought further exploration of hypothetical possibilities was not appropriate until the lump was removed and tested.

Ms. Montgomery left Dr. Richmond’s office disappointed. She was anxious. To cope with the situation and to make the necessary decisions, she felt she needed to understand fully what might lay ahead. She discussed her views with her husband and decided to seek another surgeon, one who would answer her questions.

Ms. Montgomery did not receive patient-centered care. The role she sought—but was not permitted—is a third option for patients participating in their own healthcare teams, a role different from the one chosen by Mr. Trudell and different from the one chosen by Ms. Belmonte. Ms. Montgomery wanted more than partnership in making decisions about her care. She wanted to make the decisions herself. She wanted to discuss the situation thoroughly with her surgeon, other physicians, and her husband, but she did not want her surgeon (or anyone else) to make the final decisions. Nor was she interested in shared decision making.

Dr. Richmond was polite but did not accept Ms. Montgomery’s concept of her role as a patient. Dr. Richmond appeared to believe that she knew best and that it served no useful purpose to discuss a long list of questions—and possibly that a long discussion would cause harm by adding to Ms. Montgomery’s distress. The surgeon intended to discuss matters further with Ms. Montgomery and her husband after testing provided more information about the cancer, information that would narrow the range of possible courses of action and thus simplify the discussion. There was a mismatch between Ms. Montgomery’s choice of role in her health care and the role that her surgeon was willing to permit her to have. The surgeon’s care of her was not centered on Ms. Montgomery’s wants and needs. The failure of Dr. Richmond to provide what Ms. Montgomery wanted highlights the nature of the role that Ms. Montgomery sought and the gap between patient-centered care and the care that Dr. Richmond thought was appropriate. Ms. Montgomery had a clear notion of how she wanted to participate in her own healthcare team. It was also clear to her that it was time to move on to some other surgeon and team.

Models of the Patient-Team Relationship

Models of the Patient-Team Relationship

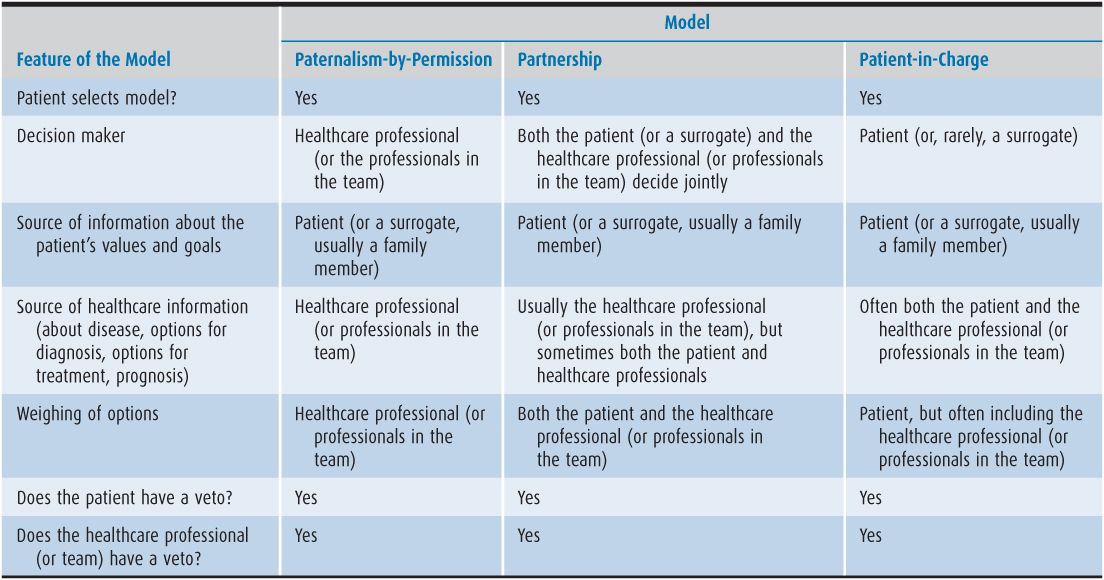

The roles of Mr. Trudell and Ms. Belmonte, and the role that Ms. Montgomery sought (but was not permitted to exercise), can be drawn together in a framework for understanding the roles that patients can have in healthcare teams. These roles represent variants of patient-centered care, each variant flowing from a different choice available to the patient.

Table 4–1 summarizes different models of the patient-team relationship. For the health care of small children, the models are models of the parent-team relationship. Although the models do apply to doctor-patient relationships they are not limited to patients and physicians. They apply to the relationships between the patient and each of the members of the healthcare team and the team as whole. If, at a given point in time, the patient is interacting with only one healthcare professional, then the relationship is the patient-doctor relationship, or the patient-nurse relationship, and so on.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree