Patient Education

Objectives

• Identify the appropriate topics that address a patient’s health education needs.

• Describe the similarities and differences between teaching and learning.

• Identify the role of the nurse in patient education.

• Identify the purposes of patient education.

• Use communication principles when providing patient education.

• Describe the domains of learning.

• Identify basic learning principles.

• Discuss how to integrate education into patient-centered care.

• Differentiate factors that determine readiness to learn from those that determine ability to learn.

• Compare and contrast the nursing and teaching processes.

• Write learning objectives for a teaching plan.

• Establish an environment that promotes learning.

• Include patient teaching while performing routine nursing care.

Key Terms

Affective learning, p. 331

Analogies, p. 341

Cognitive learning, p. 330

Functional illiteracy, p. 337

Health literacy, p. 337

Learning, p. 329

Learning objective, p. 330

Motivation, p. 332

Psychomotor learning, p. 331

Reinforcement, p. 340

Return demonstration, p. 341

Self-efficacy, p. 332

Teaching, p. 329

![]()

Patient education is one of the most important roles for a nurse in any health care setting. Shorter hospital stays, increased demands on nurses’ time, an increase in the number of chronically ill patients, and the need to give acutely ill patients meaningful information quickly emphasize the importance of quality patient education. As nurses try to find the best way to educate patients, the general public has become more assertive in seeking knowledge, understanding health, and finding resources available within the health care system. Nurses provide patients with information needed for self-care to ensure continuity of care from the hospital to the home (Falvo, 2010).

Patients have the right to know and be informed about their diagnoses, prognoses, and available treatments to help them make intelligent, informed decisions about their health and lifestyle. Part of patient-centered care is to integrate educational approaches that acknowledge patients’ expertise with their own health. Creating a well-designed, comprehensive teaching plan that fits a patient’s unique learning needs reduces health care costs, improves the quality of care, and ultimately changes behaviors to improve patient outcomes. Ultimately this helps patients make informed decisions about their care and become healthier and more independent (Edelman and Mandle, 2010; Villablanca et al., 2010).

Standards for Patient Education

Patient education has long been a standard for professional nursing practice. All state Nurse Practice Acts recognize that patient teaching falls within the scope of nursing practice (Bastable, 2006). In addition, various accrediting agencies set guidelines for providing patient education in health care institutions. For example, The Joint Commission (TJC, 2011) sets standards for patient and family education. These standards require nurses and the health care team to assess patients’ learning needs and provide education about many topics, including medications, nutrition, the use of medical equipment, pain, and the patient’s plan of care. Successful accomplishment of the standards requires collaboration among health care professionals and enhances patient safety. Educational efforts should be patient-centered by taking into consideration patients’ own education and experience, their desire to actively participate in the educational process, and their psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural values. It is important to document evidence of successful patient education in patients’ medical records. Standards such as these help to direct your patient education.

Purposes of Patient Education

The goal of educating others about their health is to help individuals, families, or communities achieve optimal levels of health (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Patient education is an essential component of providing safe, patient-centered care (QSEN, 2010). In addition, providing education about preventive health care helps reduce health care costs and hardships on individuals, families, and communities. Patients now know more about health and want to be involved in health maintenance. Provide education about health and health care in places that are convenient and familiar to patients. Comprehensive patient education includes three important purposes, each involving a separate phase of health care.

Maintenance and Promotion of Health and Illness Prevention

As a nurse you are a visible, competent resource for patients who want to improve their physical and psychological well-being. In the school, home, clinic, or workplace you provide information and skills that enable patients to assume healthier behaviors. For example, in childbearing classes you teach expectant parents about physical and psychological changes in the woman and fetal development. After learning about normal childbearing, the mother who applies new knowledge is more likely to eat healthy foods, engage in physical exercise, and avoid substances that can harm the fetus. Promoting healthy behavior through education allows patients to assume more responsibility for their health (Longo et al., 2010). Greater knowledge results in better health maintenance habits. When patients become more health conscious, they are more likely to seek early diagnosis of health problems (Hawkins et al., 2011; Redman, 2007).

Restoration of Health

Injured or ill patients need information and skills to help them regain or maintain their levels of health. Patients recovering from and adapting to changes resulting from illness or injury often seek information about their condition. For example, a woman who recently had a hysterectomy asks about her pathology reports and expected length of recovery. However, some patients find it difficult to adapt to illness and become passive and uninterested in learning. As the nurse you learn to identify patients’ willingness to learn and motivate interest in learning (Redman, 2007). The family often is a vital part of a patient’s return to health. Family caregivers often require as much education as the patient, including information on how to perform skills within the home. If you exclude the family from a teaching plan, conflicts can occur. However, do not assume that the family should be involved; assess the patient-family relationship before providing education for family caregivers.

Coping with Impaired Functions

Not all patients fully recover from illness or injury. Many have to learn to cope with permanent health alterations. New knowledge and skills are often necessary for patients to continue activities of daily living. For example, a patient loses the ability to speak after larynx surgery and has to learn new ways of communicating. Changes in function are physical or psychosocial. In the case of serious disability such as following a stroke or a spinal cord injury, the patient’s family needs to understand and accept many changes in his or her physical capabilities. The family’s ability to provide support results in part from education, which begins as soon as you identify the patient’s needs and the family displays a willingness to help. Teach family members to help the patient with health care management (e.g., giving medications through gastric tubes and doing passive range-of-motion exercises). Families of patients with alterations such as alcoholism, mental retardation, or drug dependence learn to adapt to the emotional effects of these chronic conditions and provide psychosocial support to facilitate the patient’s health. Comparing the desired level of health with the actual state of health enables you to plan effective teaching programs.

Teaching and Learning

It is impossible to separate teaching from learning. Teaching is an interactive process that promotes learning. It consists of a conscious, deliberate set of actions that help individuals gain new knowledge, change attitudes, adopt new behaviors, or perform new skills (Billings and Halstead, 2009). A teacher provides information that prompts the learner to engage in activities that lead to a desired change.

Learning is the purposeful acquisition of new knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and skills (Bastable, 2008). Complex patterns are required if the patient is to learn new skills, change existing attitudes, transfer learning to new situations, or solve problems (Redman, 2007). A new mother exhibits learning when she demonstrates how to bathe her newborn. The mother shows transfer of learning when she uses the principles she learned about bathing a newborn when she bathes her older child. Generally teaching and learning begin when a person identifies a need for knowing or acquiring an ability to do something. Teaching is most effective when it responds to the learner’s needs (Redman, 2007). The teacher assesses these needs by asking questions and determining the learner’s interests. Interpersonal communication is essential for successful teaching to occur (see Chapter 24).

Role of the Nurse in Teaching and Learning

Nurses have an ethical responsibility to teach their patients (Heiskell, 2010). In The Patient Care Partnership, the American Hospital Association (2003) indicates that patients have the right to make informed decisions about their care. The information required to make informed decisions must be accurate, complete, and relevant to patients’ needs.

TJC’s Speak Up Initiatives helps patients understand their rights when receiving medical care (TJC, 2010). The assumption is that patients who ask questions and are aware of their rights have a greater chance of getting the care they need when they need it. The program offers the following Speak Up tips to help patients become more involved in their treatment:

• Ask a trusted family member or friend to be your advocate (advisor or supporter).

• Participate in all decisions about your treatment. You are the center of the health care team.

In addition, patients are advised that they have a right to be informed about the care they will receive, obtain information about care in their preferred language, know the names of their caregivers, receive treatment for pain, receive an up-to-date list of current medications, and expect that they will be heard and treated with respect.

Teach information that patients and their families need. You frequently clarify information provided by health care providers and are the primary source of information that patients need to adjust to health problems (Bastable, 2006). However, it is also important to understand patients’ preferences for what they wish to learn. For example, a patient requests information about a new medication, or family members question the reason for their mother’s pain. Identifying the need for teaching is easy when patients request information. However, a patient’s need for teaching is often less obvious. To be an effective educator, the nurse has to do more than just pass on facts. Carefully determine what patients need to know and find the time when they are ready to learn. When nurses value and provide education, patients are better prepared to assume health care responsibilities. Nursing research about patient education supports the positive impact of patient education on patient outcomes (Box 25-1).

Teaching as Communication

The teaching process closely parallels the communication process (see Chapter 24). Effective teaching depends in part on effective interpersonal communication. A teacher applies each element of the communication process while providing information to learners. Thus the teacher and learner become involved together in a teaching process that increases the learner’s knowledge and skills.

The steps of the teaching process are similar to those of the communication process. You use patient requests for information or perceive a need for information because of a patient’s health restrictions or the recent diagnosis of an illness. Then you identify specific learning objectives to describe what the learner will be able to do after successful instruction.

The nurse is the sender who conveys a message to the patient. Many intrapersonal variables influence your style and approach. Attitudes, values, emotions, cultural perspective, and knowledge influence the way information is delivered. Past experiences with teaching are also helpful for choosing the best way to present necessary content.

The receiver in the teaching-learning process is the learner. A number of intrapersonal variables affect motivation and ability to learn. Patients are ready to learn when they express a desire to do so and are more likely to receive the message when they understand the content. Attitudes, anxiety, and values influence the ability to understand a message. The ability to learn depends on factors such as emotional and physical health, education, cultural perspective, patients’ values about their health, the stage of development, and previous knowledge.

Effective communication involves feedback. An effective teacher provides a mechanism for evaluating the success of a teaching plan and then provides positive reinforcement (Bastable, 2008; Redman, 2007). Examples of ways to evaluate teaching sessions through feedback include having a patient demonstrate a newly learned skill or asking a patient to describe how the correct dosage schedule for a new medication will be incorporated into a daily routine. Feedback needs to show the success of the learner in achieving objectives (i.e., the learner verbalizes information or provides a return demonstration of skills learned).

Domains of Learning

Learning occurs in three domains: cognitive (understanding), affective (attitudes), and psychomotor (motor skills) (Bloom, 1956; Bastable, 2008). Any health topic involves one or all domains or any combination of the three. You often work with patients who need to learn in each domain. For example, patients diagnosed with diabetes need to learn how diabetes affects the body and how to control blood glucose levels for healthier lifestyles (cognitive domain). In addition, patients begin to accept the chronic nature of diabetes by learning positive coping mechanisms (affective domain). Finally, many patients living with diabetes learn to test their blood glucose levels at home. This requires learning how to use a glucose meter (psychomotor domain). The characteristics of learning within each domain influence the teaching and evaluation methods used. Understanding each learning domain prepares the nurse to select proper teaching techniques and apply the basic principles of learning (Box 25-2).

Cognitive Learning

Cognitive learning includes all intellectual behaviors and requires thinking (Bastable, 2008). In the hierarchy of cognitive behaviors the simplest behavior is acquiring knowledge, whereas the most complex is evaluation. Cognitive learning includes the following:

• Knowledge: Learning new facts or information and being able to recall them

• Comprehension: The ability to understand the meaning of learned material

• Application: Using abstract, newly learned ideas in a concrete situation

• Analysis: Breaking down information into organized parts

• Synthesis: The ability to apply knowledge and skills to produce a new whole

• Evaluation: A judgment of the worth of a body of information for a given purpose

Affective Learning

Affective learning deals with expression of feelings and acceptance of attitudes, opinions, or values. Values clarification (see Chapter 22) is an example of affective learning. The simplest behavior in the hierarchy is receiving, and the most complex is characterizing (Krathwohl et al., 1964). Affective learning includes the following:

• Receiving: Being willing to attend to another person’s words

• Responding: Active participation through listening and reacting verbally and nonverbally

• Valuing: Attaching worth to an object or behavior demonstrated by the learner’s behavior

• Organizing: Developing a value system by identifying and organizing values and resolving conflicts

• Characterizing: Acting and responding with a consistent value system

Psychomotor Learning

Psychomotor learning involves acquiring skills that require the integration of mental and muscular activity such as the ability to walk or use an eating utensil (Redman, 2007). The simplest behavior in the hierarchy is perception, whereas the most complex is origination. Psychomotor learning includes the following:

Basic Learning Principles

To teach effectively and efficiently, you first need to understand how people learn (Eshleman, 2008). Motivation addresses a person’s desire or willingness to learn (Redman, 2007). The patient’s willingness to become involved in learning influences your teaching approach. Previous knowledge, experience, attitudes, and sociocultural factors influence a person’s motivation. The ability to learn depends on physical and cognitive attributes, developmental level, physical wellness, and intellectual thought processes. An ideal learning environment allows a person to attend to instruction.

A person’s learning style affects preferences for learning. People process information in the following ways: by seeing and hearing, reflecting and acting, reasoning logically and intuitively, and analyzing and visualizing. Some people learn information gradually, whereas others learn more sporadically. Effective teaching plans include a combination of approaches that meet multiple learning styles (Billings and Halstead, 2009).

Motivation to Learn

Attentional Set

An attentional set is the mental state that allows the learner to focus on and comprehend a learning activity. Before learning anything, patients must give attention to, or concentrate on, the information to be learned. Physical discomfort, anxiety, and environmental distractions influence the ability to attend. Therefore determine the patient’s level of comfort before beginning a teaching plan and ensure that the patient is able to focus on the information.

As anxiety increases, the patient’s ability to pay attention often decreases. Anxiety is uneasiness or worry resulting from anticipating a threat or danger. When faced with change or the need to act differently, a person feels anxious. Learning requires a change in behavior and thus produces anxiety. A mild level of anxiety motivates learning. However, a high level of anxiety prevents learning from occurring. It incapacitates a person, creating an inability to focus on anything other than relieving the anxiety. Manage the patient’s anxiety (see Chapter 37) before educating to improve the patient’s comprehension and understanding of the information given (Fredericks et al., 2008).

Motivation

Motivation is a force that acts on or within a person (e.g., an idea, emotion, or a physical need) to cause the person to behave in a particular way (Redman, 2007). If a person does not want to learn, it is unlikely that learning will occur. Motivation sometimes results from a social, task mastery, or physical motive.

A social motive is a need for connection, social approval, or self-esteem. People normally seek out others with whom they can compare opinions, abilities, and emotions. For example, new parents often seek validation of ideas and parenting techniques from others whom they have identified as role models in their social environment or health care workers with whom they have established a relationship.

Task mastery motives are based on needs such as achievement and competence. For example, a high school senior who has diabetes begins to test blood glucose levels and make decisions about insulin dosages in preparation for leaving home and establishing independence. The ability to successfully manage diabetes provides the motivation to master the task or skill. After a person succeeds at a task, he or she is usually motivated to achieve more.

Often patient motives are physical. Some patients are motivated to return to a level of physical normalcy. For example, a patient with a below-the-knee amputation is motivated to learn how to walk with assistive devices. Knowledge that is necessary for survival, problem recognition, and critical decision making creates a stronger stimulus for learning than knowledge that merely promotes health (Bastable, 2006).

You assess a patient’s motivation to learn and what the patient needs to know to promote compliance with their prescribed therapy. Unfortunately not all people are interested in maintaining health. Many do not adopt new health behaviors or change unhealthy behaviors unless they perceive a disease as a threat, overcome barriers to changing health practices, and see the benefits of adopting a healthy behavior. For example, some patients with lung disease continue to smoke. No therapy has an effect unless a person believes that health is important.

Use of Theory to Enhance Motivation and Learning

Health education often involves changing attitudes and values that are not easy to change by simply teaching facts. Therefore it is important for you to use various interventions based on theory when developing patient education plans. Because of the complexity of the patient education process, different theories and models are available to guide patient education. Using a theory that matches the patient’s needs in practice will provide more effective patient education. Social learning theory provides one of the most useful approaches to patient education because it explains the characteristics of the learner and guides the educator in developing effective teaching interventions that result in enhanced learning and improved motivation (Bandura, 2001; Stonecypher, 2009).

According to social learning theory, people continuously attempt to control events that affect their lives. This allows them to attain desired outcomes and avoid undesired outcomes, resulting in improved motivation. Self-efficacy, a concept included in social learning theory, refers to a person’s perceived ability to successfully complete a task. When people believe that they are able to execute a particular behavior, they are more likely to perform the behavior consistently and correctly (Bandura, 1997).

Self-efficacy beliefs come from four sources: enactive mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological and affective states (Bandura, 1997). Understanding the four sources of self-efficacy allows you to develop interventions to help patients adopt healthy behaviors. For example, a nurse who is wishing to teach a child recently diagnosed with asthma how to correctly use an inhaler expresses personal belief in the child’s ability to use the inhaler (verbal persuasion). Then the nurse demonstrates how to use the inhaler (vicarious experience). Once the demonstration is complete, the child uses the inhaler (enactive mastery experience). As the child’s wheezing and anxiety decrease after the correct use of the inhaler, he or she experiences positive feedback, further enhancing his or her confidence to use it (physiological and affective states). Interventions such as these enhance perceived self-efficacy, which in turn improves the achievement of desired outcomes.

Self-efficacy is a concept included in many health promotion theories because it often is a strong predictor of healthy behaviors and because many interventions improve self-efficacy, resulting in improved lifestyle choices (Bandura, 1997). Because of its use in theories and research studies, many evidence-based teaching interventions include a focus on self-efficacy. When nurses implement interventions to enhance self-efficacy, their patients frequently experience positive outcomes. For example, researchers associated interventions that include self-efficacy with effective management of heart failure (While and Kiek, 2009; Yehle and Plake, 2010), participation in physical activity (Ashford et al., 2010), self-management of arthritis (Nunez et al., 2009), and improved management of asthma in children (Coffman et al., 2009).

Psychosocial Adaptation to Illness

A temporary or permanent loss of health is often difficult for patients to accept. They need to grieve, and the process of grieving gives them time to adapt psychologically to the emotional and physical implications of illness. The stages of grieving (see Chapter 36) include a series of responses that patients experience during a loss such as illness. They experience these stages at different rates and sequences, depending on their self-concept before illness, the severity of the illness, and the changes in lifestyle that the illness creates. Effective, supportive care guides the patient through the grieving process.

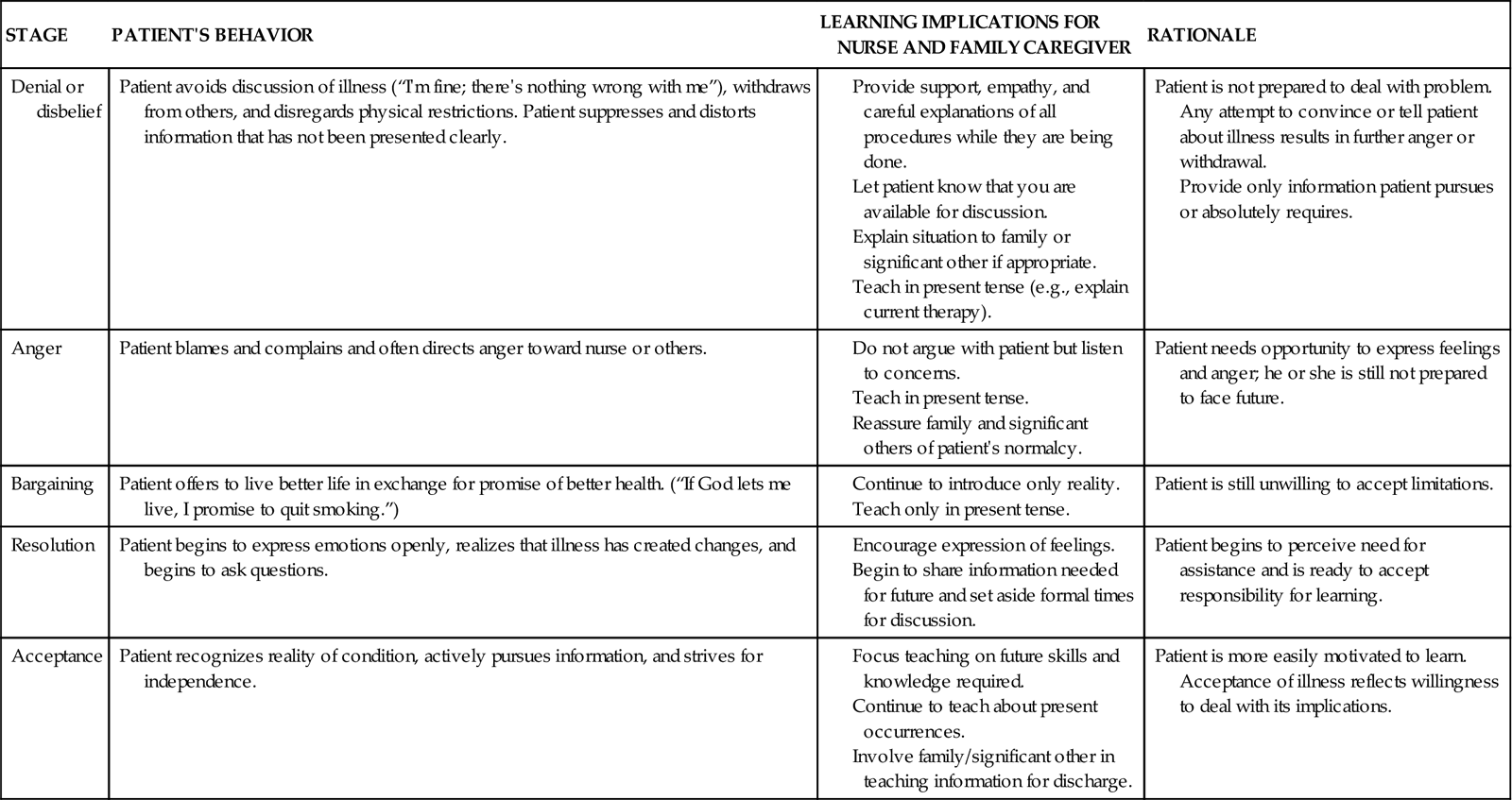

Readiness to learn is related to the stage of grieving (Table 25-1). Patients cannot learn when they are unwilling or unable to accept the reality of illness. However, properly timed teaching facilitates adjustment to illness or disability. Identify the patient’s stage of grieving on the basis of his or her behaviors. When the patient enters the stage of acceptance, the stage compatible with learning, introduce a teaching plan. Continuous assessment of the patient’s behaviors determines the stages of grieving. Teaching continues as long as the patient remains in a stage conducive to learning.

TABLE 25-1

Relationship Between Psychosocial Adaptation to Illness, Grief, and Learning

Active Participation

Learning occurs when the patient is actively involved in the educational session (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). A patient’s involvement in learning implies an eagerness to acquire knowledge or skills. It also improves the opportunity for the patient to make decisions during teaching sessions. For example, when teaching car seat safety during a parenting class, hold a teaching session in the parking lot where the participants park their cars. Encourage active participation by providing the learners with several different car seats for them to place in their cars. At the completion of this session, the parents are able to determine which type of car seat fits in their cars and which is the easiest to use. This provides participants with the information needed to purchase the appropriate car seat.

Ability to Learn

Developmental Capability

Cognitive development influences the patient’s ability to learn. You can be a competent teacher, but if you do not consider the patient’s intellectual abilities, teaching is unsuccessful. Learning, like developmental growth, is an evolving process. You need to know the patient’s level of knowledge and intellectual skills before beginning a teaching plan. Learning occurs more readily when new information complements existing knowledge. For example, measuring liquid or solid food portions requires the ability to perform mathematical calculations. Reading a medication label or discharge instructions requires reading and comprehension skills. Learning to regulate insulin dosages requires problem-solving skills.

Learning in Children

The capability for learning and the type of behaviors that children are able to learn depend on the child’s maturation. Without proper physiological, motor, language, and social development, many types of learning cannot take place. However, learning occurs in children of all ages. Intellectual growth moves from the concrete to the abstract as the child matures. Therefore information presented to children needs to be understandable, and the expected outcomes must be realistic, based on the child’s developmental stage (Box 25-3). Use teaching aids that are developmentally appropriate (Fig. 25-1). Learning occurs when behavior changes as a result of experience or growth (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Adult Learning

Teaching adults differs from teaching children. Adults are able to critically reflect on their current situation and sometimes need help to see their problems and change their perspectives (Redman, 2007). Because adults become independent and self-directed as they mature, they are often able to identify their own learning needs (Billings and Halstead, 2009). Learning needs come from problems or tasks that result from real-life situations. Although adults tend to be self-directed learners, they often become dependent in new learning situations. The amount of information provided and the amount of time that is spent with the adult patient vary, depending on the patient’s personal situation and readiness to learn. An adult’s readiness to learn is often associated with his or her developmental stage and other events that are occurring in his or her life. Resolve any needs or issues that the patient perceives as extremely important so learning can occur.

Adults have a wide variety of personal and life experiences on which to draw. Therefore enhance adult learning by encouraging them to use these experiences to solve problems (Eshleman, 2008). Furthermore, make education patient-centered by developing educational topics and goals in collaboration with the adult patient. Adult patients are ultimately responsible for changing their own behavior. Assessing what the adult patient currently knows, teaching what the patient wants to know, and setting mutual goals improve the outcomes of patient education (Bastable, 2008).

Physical Capability

The ability to learn often depends on the patient’s level of physical development and overall physical health. To learn psychomotor skills, a patient needs to possess a certain level of strength, coordination, and sensory acuity. For example, it is useless to teach a patient to transfer from a bed to a wheelchair if he or she has insufficient upper body strength. An older patient with poor eyesight or the inability to grasp objects tightly cannot learn to apply an elastic bandage. Therefore do not overestimate the patient’s physical development or status. The following physical characteristics are necessary to learn psychomotor skills:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree