Chapter 4 Linda Bucher and Catherine N. Kotecki 1. Prioritize patient teaching goals for diverse patients and caregivers. 2. Analyze teaching implications related to the diverse needs of adult learners. 3. Apply strategies to manage challenges to nurse-teacher effectiveness. 4. Evaluate the role of the caregiver in patient teaching. 5. Apply the teaching-learning process to diverse patient populations. 6. Relate the physical, psychologic, and sociocultural characteristics of the patient and caregiver to the teaching-learning process. 7. Select appropriate teaching strategies for diverse patient populations. 8. Select appropriate methods to evaluate patient and caregiver teaching. General goals of patient teaching include health promotion, prevention of disease, management of illness, and appropriate selection and use of treatment options. In patients with acute and chronic health problems, teaching can prevent complications and promote recovery, self-care, and independence. Seventy percent of the deaths in the United States are due to chronic illnesses, illnesses with which patients often live for many years.1 Whether patients adequately manage their health problems and maintain quality of life depends on what they learn about their conditions and what they choose to do with this knowledge. Patients who understand their discharge teaching, including how to take their medicines and when to follow-up with their health care providers, are 30% less likely to be readmitted or visit the emergency department than patients who did not receive this information.2 eTABLE 4-1 WRITING LEARNING OBJECTIVES/GOALS • The patient will demonstrate to the nurse the correct technique for changing his colostomy bag by discharge. • In front of the nurse, the patient will administer a subcutaneous injection of insulin to herself using correct technique within 1 week. • The patient will select breakfast, lunch, and dinner menus keeping within a 2000 mg sodium diet for 3 consecutive days with 90% accuracy. • Given a list of symptoms of heart failure, the patient will identify the early symptoms of heart failure with 80% accuracy before discharge from the hospital. Teaching may occur wherever you work. Although institutions may employ advanced practice nurses and patient educators to establish and oversee patient teaching programs, you are always responsible for patient and caregiver teaching.3–5 It is a responsibility that cannot be delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel. Teaching is not just imparting information. Teaching is a process of deliberately arranging conditions to promote learning that results in a change in behavior.6 Teaching can be a planned or informal experience. It uses a combination of methods such as instruction, counseling, and behavior modification. Learning is acquiring knowledge and/or skills. It can result in a permanent change in a person.6 Observation of this change is an indication that learning has occurred. Learning may also result in a potential or capability to change behavior. This is seen in a patient who understands the instruction and is fully informed, but chooses not to change behavior. In this case, teaching gives the patient the capability to make a decision to change behavior, but the decision is the patient’s. Understanding how and why adults learn is important for you to effectively teach patients and their caregivers. Many of the theories of adult learning have risen from the work of Malcolm Knowles, who identified six principles of andragogy (adult learning) that are important for you to consider when teaching adults7 (Table 4-1). TABLE 4-1 ADULT LEARNING PRINCIPLES APPLIED TO PATIENT AND CAREGIVER TEACHING When a change in health behaviors is recommended, patients and their caregivers may progress through a series of steps before they are willing or able to accept the change. Prochaska and Velicer proposed six stages of change in their Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change8 (Table 4-2). This model is frequently used to help patients stop smoking, manage diabetes, and lose weight. TABLE 4-2 STAGES OF CHANGE IN TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL Adapted from Prochaska J, Velicer W: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change, Am J Health Promot 12:38, 1997. (Classic) Motivational interviewing (see www.motivationalinterview.org) uses nonconfrontational interpersonal communication techniques to motivate patients to change behavior.9 This strategy includes the use of any intervention that enhances the patient’s motivation for change (Table 4-3). The techniques used in motivational interviewing are linked to the stages of change as identified by Prochaska and Velicer. TABLE 4-3 KEY ASPECTS OF MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING During the process of change, relapse and recycling through the stages are expected. Sometimes patients do not change behaviors or return to previous behaviors after a period of change. This may indicate that the interventions used did not consider the patient’s stage of change.10 Identify the patient’s current stage of readiness for change and the stage to which the patient is moving. Patients who are in the early stages of change need and use different kinds of motivational support than patients at later stages of change. As the patient moves from contemplation to preparation, a commitment to change is strengthened by helping the patient develop self-efficacy, which is the belief that one can succeed in a given situation. In this case it is the patient’s belief that substance-use behaviors can be changed. Support even the smallest effort to change. Movement through action and maintenance stages of change requires continued support to increase the patient’s involvement and participation in treatment. A comprehensive discussion of motivational interviewing is presented in the Treatment Improvement Protocols available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK14856. Nonverbal communication is critical when teaching. Nonverbal communication is often guided by cultural practices. For example, in Western culture, sitting in an open, relaxed position facing the patient with eyes at the same level delivers a positive, nonverbal message (Fig. 4-1). In a hospital setting this may require raising the patient’s bed or sitting in a chair at the bedside. Open body gestures communicate interest and a willingness to share. With patients from Eastern cultures, you may need to avoid direct eye contact and provide health information to a family spokesperson rather than directly to the patient. Approximately one in four American adults provides care to someone on a daily basis. Caregivers are often categorized by their relationship to the patient. The most common types of caregivers are spouses, adult children, parents, grandparents, and life partners. Although older adult women are the most common family caregivers, other examples include husbands who care for wives with Alzheimer’s disease, adult children who care for a parent with a stroke, grandparents who care for a grandchild with a developmental disorder, parents who care for an adult child with a spinal cord injury, and life partners who care for loved ones with a variety of health problems.11 Identify the key caregiver(s) for the patient. Assess the caregiver’s roles and relationships to the patient. The patient’s health problem affects family roles and functions. Identify the needs of caregivers, whether it is in the acute care setting, during the transition to home, or in a home setting12 (Table 4-4). TABLE 4-4 Consider cultural differences when assessing the caregiver. In some cultures a male family member may be the designated spokesperson. This person would receive and communicate information among family members and the patient. In planning for discharge to home, it is important to include caregivers who will actually provide the care for the patient, along with the family spokesperson.12 As much as possible, teach the caregiver along with the patient. Explain the goals of the teaching plan clearly to both of them. Caregivers may need assistance to learn the physical and technical requirements of care, find resources for home care, locate equipment and supplies, and rearrange the home environment to accommodate the patient. Sources of support for the transition from hospital to home include community-based agencies, Medicare and Medicaid offices, and case managers at the hospital and insurance companies.13 Patients and caregivers may have different teaching needs. For example, the first priority of an older diabetic patient with a large leg ulcer may be to learn how to transfer from a bed to a chair in the least painful manner. On the other hand, the caregiver may be most concerned about learning the technique for dressing changes. Both the patient’s and the caregiver’s learning needs are important. The patient and the caregiver may also have differing or conflicting views of the illness and treatment options. Developing a successful teaching plan requires you to view the patient’s needs within the context of the caregiver’s needs. For instance, you may teach a patient with right-sided paresis (weakness) self-feeding techniques with special implements, but at a home visit you find the patient being fed by the caregiver. On questioning, the caregiver reveals that it is too difficult to watch the patient struggle with feeding, it takes too long, and it is messy. As a result, the caregiver decides that it is easier to just feed the patient. This is an example of a situation in which both the patient and caregiver need additional teaching about the goals of self-care. Caregiver responsibilities are usually taken on gradually with the progression of the patient’s illness. As the caregiving responsibilities become more demanding, caregivers often realize that their lives have changed because of this experience. Overwhelmingly, caregivers want to continue their usual activities (e.g., work) despite the hardships they face in caring for acute and chronically ill patients.14,15 Prolonged periods of caregiving coupled with a patient’s life-limiting illness can contribute to stress and burnout. Some common caregiver stressors are listed in Table 4-5. As caregiving progresses, stressors may change. For example, a caregiver may initially need only to adjust work schedules to accommodate a patient’s health care appointments. Later, as the patient’s condition worsens, the caregiver may have to reduce work hours, incurring financial hardships. TABLE 4-5

Patient and Caregiver Teaching

Role of Patient and Caregiver Teaching

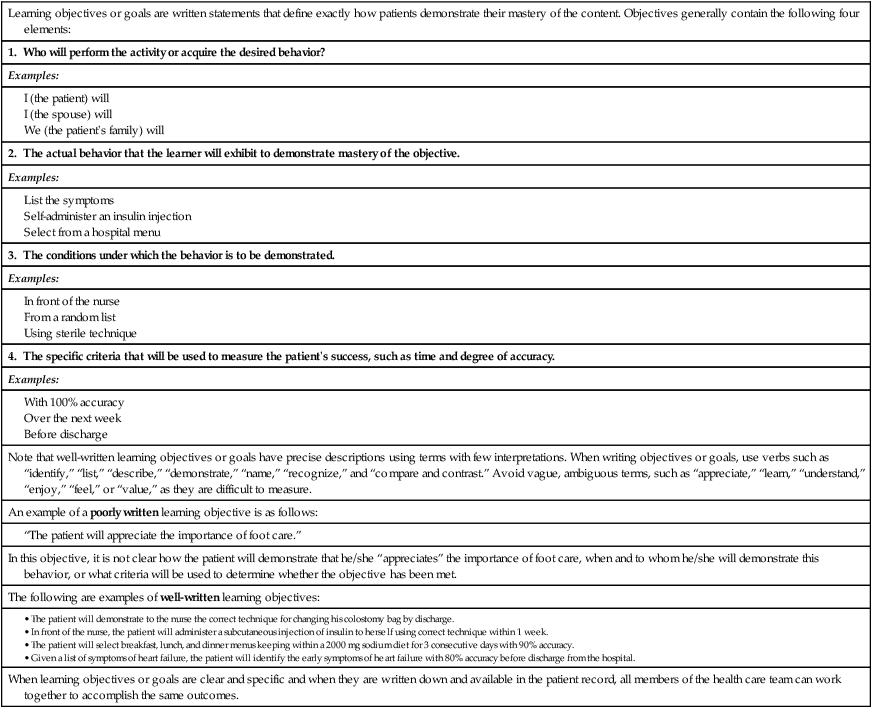

Learning objectives or goals are written statements that define exactly how patients demonstrate their mastery of the content. Objectives generally contain the following four elements:

1. Who will perform the activity or acquire the desired behavior?

Examples:

2. The actual behavior that the learner will exhibit to demonstrate mastery of the objective.

Examples:

3. The conditions under which the behavior is to be demonstrated.

Examples:

4. The specific criteria that will be used to measure the patient’s success, such as time and degree of accuracy.

Examples:

Note that well-written learning objectives or goals have precise descriptions using terms with few interpretations. When writing objectives or goals, use verbs such as “identify,” “list,” “describe,” “demonstrate,” “name,” “recognize,” and “compare and contrast.” Avoid vague, ambiguous terms, such as “appreciate,” “learn,” “understand,” “enjoy,” “feel,” or “value,” as they are difficult to measure.

An example of a poorly written learning objective is as follows:

In this objective, it is not clear how the patient will demonstrate that he/she “appreciates” the importance of foot care, when and to whom he/she will demonstrate this behavior, or what criteria will be used to determine whether the objective has been met.

The following are examples of well-written learning objectives:

When learning objectives or goals are clear and specific and when they are written down and available in the patient record, all members of the health care team can work together to accomplish the same outcomes.

Teaching-Learning Process

Adult Learner

Adult Learning Principles.

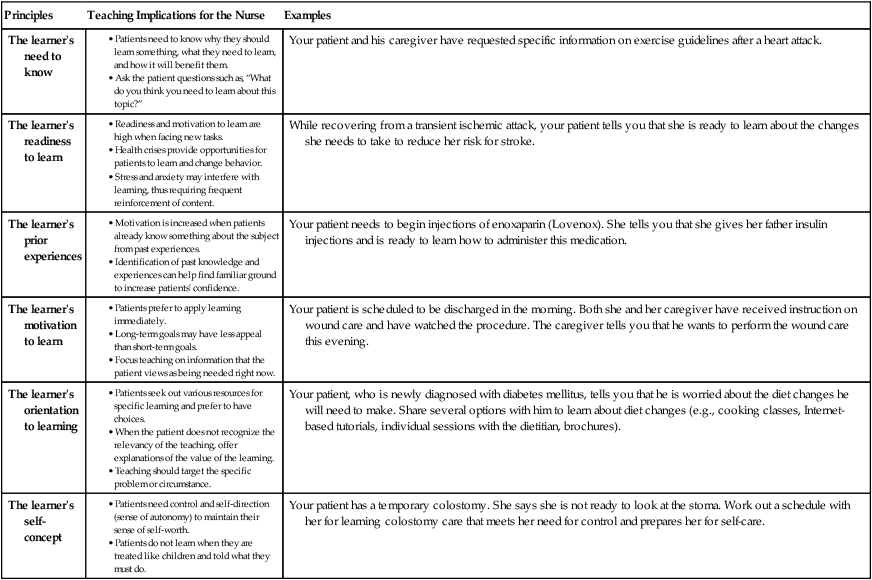

Principles

Teaching Implications for the Nurse

Examples

The learner’s need to know

Your patient and his caregiver have requested specific information on exercise guidelines after a heart attack.

The learner’s readiness to learn

While recovering from a transient ischemic attack, your patient tells you that she is ready to learn about the changes she needs to take to reduce her risk for stroke.

The learner’s prior experiences

Your patient needs to begin injections of enoxaparin (Lovenox). She tells you that she gives her father insulin injections and is ready to learn how to administer this medication.

The learner’s motivation to learn

Your patient is scheduled to be discharged in the morning. Both she and her caregiver have received instruction on wound care and have watched the procedure. The caregiver tells you that he wants to perform the wound care this evening.

The learner’s orientation to learning

Your patient, who is newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, tells you that he is worried about the diet changes he will need to make. Share several options with him to learn about diet changes (e.g., cooking classes, Internet-based tutorials, individual sessions with the dietitian, brochures).

The learner’s self-concept

Your patient has a temporary colostomy. She says she is not ready to look at the stoma. Work out a schedule with her for learning colostomy care that meets her need for control and prepares her for self-care.

Models to Promote Health.

Stage

Patient Behavior

Nursing Implications

1. Precontemplation

Is not considering a change. Is not ready to learn.

Provide support, increase awareness of condition. Describe benefits of change and risks of not changing.

2. Contemplation

Thinks about a change. May verbalize recognition of need to change; says “I know I should,” but identifies barriers.

Introduce what is involved in changing the behavior. Reinforce the stated need to change.

3. Preparation

Starts planning the change, gathers information, sets a date to initiate change, shares decision to change with others.

Reinforce the positive outcomes of change, provide information and encouragement, develop a plan, help set priorities, and identify sources of support.

4. Action

Begins to change behavior through practice. Tentative and may experience relapses.

Reinforce behavior with reward, encourage self-reward, discuss choices to help minimize relapses and regain focus. Help patient plan to deal with potential relapses.

5. Maintenance

Practices the behavior regularly. Able to sustain the change.

Continue to reinforce behavior. Provide additional teaching on the need to maintain change.

6. Termination

Change has become part of lifestyle. Behavior no longer considered a change.

Evaluate effectiveness of the new behavior. No further intervention needed.

Nurse as Teacher

Required Competencies

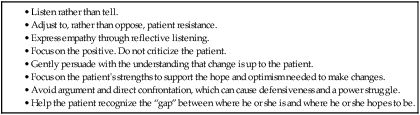

Communication Skills.

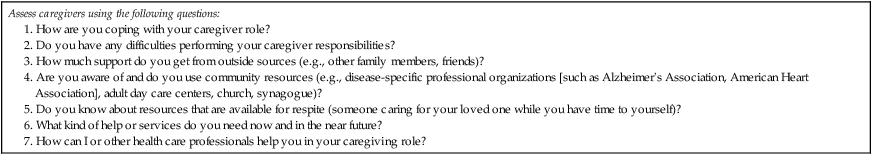

Caregiver Support in the Teaching-Learning Process

Caregiver Stress.