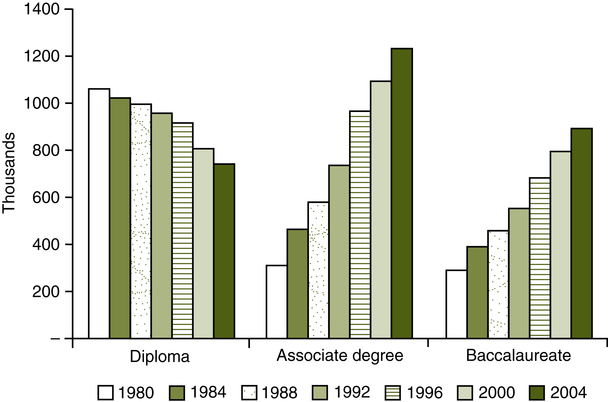

Joan L. Creasia, PHD, RN and Kathryn B. Reid, PHD, RN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Trace the history of nursing education from its inception to the present. • Compare nursing education programs for similarities and differences. • Classify nursing education programs according to role preparation, scope of practice, eligibility for licensure, and eligibility for specialty certification. • Identify and analyze trends in nursing program development, including eligibility for admission, career mobility and advancement opportunities, and program accessibility. • Evaluate the effectiveness of mechanisms to ensure program quality. • Analyze the merits and shortcomings of the current nursing education system. For individuals seeking a career in nursing, deciphering the various types of educational programs and the relationship of each program type to future nursing practice can be daunting. Many types of programs at all levels provide multiple pathways to one or more nursing credential. Chapter 1 described the social, political, and economic forces that influenced the evolution of nursing as a profession and the system of nursing education. This chapter analyzes the various educational opportunities with some considerations for selecting among the options. A brief historical overview of each type of program helps build greater understanding of the factors influencing nursing education. More important, this chapter highlights the contributions each type of program provides for contemporary health care systems, advancement of the nursing profession, and promotion of a professional workforce dedicated to lifelong learning. In 1965, the American Nurses Association (ANA) designated the baccalaureate degree as the educational entry point into professional nursing practice (ANA, 1965). Now, more than 40 years later, three educational pathways for RN licensure still exist: baccalaureate, associate degree, and diploma programs (Figure 2-1). The existence of multiple pathways contributes to a confusing landscape of nursing education and creates challenges for aspiring nurses as they try to choose the most appropriate type of program in which to enter the profession. No matter which type of entry into practice program one chooses, “the demands placed on nursing in the emerging health care system are likely to require a greater proportion of RNs who are prepared beyond the associate degree or diploma level” (Pew Health Professions Commission, 1998, p. 64). The nursing education system is challenged to balance the goal of providing adequate numbers of baccalaureate-prepared nurses while simultaneously advancing the educational level of nurses prepared at the associate degree or diploma level. Diploma programs are typically 2 to 3 years in length, and graduates are eligible to take the RN licensure examination (NCLEX-RN). As the length of diploma programs increased over the years from 4 months to 3 years, nursing students were increasingly used to meet hospital staffing needs rather than function in the student role. This exploitation of nursing students was addressed in several landmark studies of nursing and nursing education, and student life eventually became more compatible with sound educational practices. Many of these same studies also encouraged the profession to move its programs into collegiate settings (e.g., Brown, 1948; Goldmark & the Committee for the Study of Nursing Education, 1923) and to abandon the apprenticeship model. Ultimately, the high cost of these programs to students and to the hospitals that offered them, coupled with an increasing number of collegiate options, brought about the closure of many diploma programs. Most baccalaureate programs are now 4 academic years in length, and the nursing major is typically concentrated at the upper division level. Graduates are prepared as generalists to practice nursing in beginning leadership positions in a variety of settings, and they are eligible to take the NCLEX-RN. To prepare nurses for this multifaceted role, several components are essential for all baccalaureate programs. These components are liberal education, quality and patient safety, evidence-based practice, information management, health care policy and finance, communication/collaboration, clinical prevention/population health, and professional values (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2008a). The number of BSN programs has continued to increase over the past several years. In 2004, 674 baccalaureate programs existed in the United States and its territories; in 2008 the number was 748 (AACN, 2005a, 2009a). After a worrisome decline in enrollment in the late 1990s, trend data for a select group of 488 schools indicate that traditional baccalaureate student enrollment had increased an average of 6869 students per year from 2004 to 2008 (AACN, 2009a). As the nursing shortage has gained national recognition, accelerated BSN programs have emerged to hasten the time to graduation for select groups of students. Some programs accept nonnurse college graduates, and the curriculum is designed for completion in less time than the traditional BSN program through a combination of “bridge” and transition courses (AACN, 2009a). These programs are especially attractive for individuals desiring a career change. In the fall of 2008, 209 colleges and universities offered accelerated BSN programs for nonnurse college graduates (AACN, 2009a). The RN-BSN track or option in the baccalaureate program is designed to recognize and reward prior learning and to capitalize on the characteristics of the adult learner. Several models of awarding academic credit to RNs for prior education and experience exist to facilitate educational mobility. These include direct transfer of credits, credits awarded by examination, variable credits awarded after portfolio review of educational and professional experiences, the holding of lower division nursing credits in “escrow” until completion of the program, and a number of other innovative models. This reflects the AACN’s assertion that “educational mobility options should respect previous learning that students bring to the educational environment . . . and build on knowledge and skills attained by learners prior to their matriculation” (AACN, 1998, p. 1). More than 600 RN-BSN programs are offered nationwide (AACN, 2009a). LPN/LVN programs are typically located in technical or vocational education settings. Programs are 9 to 15 months long, require proof of high school graduation or its equivalent for admission, and are designed to prepare graduates to work with RNs and be supervised by them. Programs lead to a certificate of completion and eligibility to take the NCLEX-PN. More than 1500 state-approved practical/vocational nursing programs currently exist in the United States (Education-Portal, 2009). Because many courses taken by practical nurse students do not carry academic credit, these programs do not always articulate well with collegiate nursing programs. Associate degree programs, however, often have procedures for accommodation of practical nurses into their programs by way of advanced placement. In 1952 the associate degree in nursing (ADN) became another program option for those desiring to become RNs. Designed by Mildred Montag, these programs were intended to be a collegiate alternative for the preparation of technical nurses and a response to the nursing shortage (Haase, 1990). In 1958 the W. K. Kellogg Foundation funded a pilot project at seven sites in four states. The success of the pilot project led to a phenomenal growth of associate degree programs in the United States. These programs multiplied in community colleges and also began to appear at 4-year colleges and universities. By 1973 approximately 600 associate degree programs existed in the United States. Today, NLNAC states that nearly 1000 state-approved associate degree nursing programs exist (Associate Degree Nursing, 2009), of which 652 are accredited (S. Tanner, personal communication, February 10, 2010). Master’s education in nursing traces its origins to 1899, when Teachers College in New York began to offer graduate courses in nursing management and nursing education. However, master’s programs did not begin to escalate and become nationally visible until the late 1950s and early 1960s. The first programs were strong on role preparation and light on advanced nursing content. This was not surprising because the nurses teaching in these programs did not themselves hold graduate degrees in nursing. As advanced nursing content became more clearly defined, and as increasing numbers of nursing faculty became proficient at teaching it, strong advanced nursing content became the prevailing characteristic of master’s programs in nursing. Role preparation received somewhat less attention as clinical emphasis increased, and by the 1990s advanced practice had become the predominant focus for most master’s degree programs. The expanding authority of advanced practice nurses (APNs) to serve as autonomous providers of care requires that the education of the clinicians be sound and that the consumers of APN care be able to have confidence in the quality of the educational experience (Booth & Bednash, 1994, p. 2). Master’s programs in nursing are typically 1 to 2 years of full-time study and are built on the baccalaureate nursing major. The program content includes a set of graduate-level foundational (core) courses, including a research component, and clinical specialty courses. Other recommended core content areas include theoretical foundations of nursing practice, health care financing, human diversity and social issues, ethics, health promotion, health care delivery systems, health policy, and professional role development. For specialty tracks that prepare APNs, an additional clinical core consists of advanced pathophysiology, pharmacology, and advanced health/physical assessment (AACN, 1996). Master’s degree programs in nursing have experienced phenomenal growth over the past several decades. In 1973 only 86 such programs existed. By 1983 the number had increased to 154, and in 2008 there were 475 (AACN, 2009a). During the late 1980s and early 1990s, enrollment in master’s degree programs increased rapidly as the demand for APNs escalated, but a slight decline (1.9%) was evident in 1999 (AACN, 2000). The decline in enrollment reversed itself in the early 2000s, and master’s program enrollment increased by an average of 5993 students per year from 2004 to 2008 in a select group of 391 schools for which trend data were available (AACN, 2009a). Master’s degree programs currently are offered in all states and territories of the United States. The bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) degree or its equivalent is usually a requirement for admission to a master’s program in nursing, but several interesting models that accommodate other types of students have emerged. Some master’s programs admit RNs without a baccalaureate degree or with a baccalaureate degree in another field into a streamlined track that includes both baccalaureate and master’s level courses. Other programs admit students who are not nurses at all. Approximately 158 RN-MSN programs are in existence nationwide (AACN, 2009a). Master’s programs in nursing that admit nonnurse college graduates and RNs without a baccalaureate degree in nursing take the necessary steps to ensure that both groups complete whatever undergraduate or graduate prerequisite courses are needed to acquire the equivalent of a baccalaureate nursing major. They then pursue the same graduate-level foundational, specialty, and cognate courses required of master’s students; thus they exit the program having met the same program objectives that all graduates of both programs must meet. Nonnurses are eligible to take the NCLEX-RN examination on completion of the generalist or baccalaureate equivalent portion of the program or at program completion. In 2008, 55 nonnurse master’s entry programs and nearly 300 programs that offered RN-MSN options existed (AACN, 2009a). Another option regarding master’s programs in nursing is the joint program leading to two master’s degrees awarded simultaneously. This type of program is especially relevant for nurses seeking administrative positions that require both advanced nursing knowledge and business management skills. Several joint program models now exist across the country, reflecting nursing’s responsiveness to documented student need and interest and also demonstrating nursing’s ability to collaborate with other academic disciplines. Among the available programs in conjunction with the master’s degree in nursing are the master’s degree in business administration (MSN/MBA), master’s degree in public administration (MSN/MPA), and master’s degree in hospital administration (MSN/MHA). Degree candidates must be admitted to both programs and must fulfill requirements for both programs. However, requirements common to both programs may be consolidated. More than 130 such programs are currently in existence, with several more in development (AACN, 2009a). A relatively new nursing role is that of the clinical nurse leader (CNL), a master’s-prepared nurse who “oversees the care coordination of a distinct group of patients and actively provides direct patient care in complex situations” (AACN, 2005b, p. 1). The concept was developed in collaboration with leaders from education and practice settings. The AACN (2003) further describes the CNL role: “Along with the authority, autonomy, and initiative to design and implement care, the CNL is accountable for improving individual care outcomes and care processes in a quality cost-effective manner” (p. 7). The CNL role differs from advanced practice nursing roles in that the CNL is a generalist and not a specialist, as are nurse practitioners and clinical specialists. A more in-depth presentation of the role and expectations of the CNL can be found in the White Paper on the Role of the Clinical Nurse Leader (AACN, 2007). Approximately 100 schools of nursing partnering with almost 200 health care delivery organizations in 35 states and Puerto Rico were involved in a pilot project to develop the CNL role, integrate it into the health care system, and evaluate the outcomes. Currently, 77 schools of nursing are admitting students into CNL programs, and more programs are being developed (AACN, 2009b). As might be expected, given nursing’s relative youth in academe, the profession has only recently carved out a major doctoral presence in the academic community. Until 1970 fewer than a dozen doctoral programs with a major in nursing existed across the country. Most nurses who earned doctoral degrees did so in related disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, education, psychology, or physiology. In 1983, 27 doctoral programs in nursing existed. By 1990, only 7 years later, their number had nearly doubled. As the movement toward the practice doctorate gained momentum, the number of doctoral programs in nursing increased rapidly. In 2004, 93 programs existed (AACN, 2005a), and in 2008 the number of doctoral programs had increased to 158 (AACN, 2009a). Most research-focused doctoral programs admit students with an MSN degree, but a few admit students with a BSN. These programs range in length from 3 to 5 years of full-time study or that equivalent in part-time work. The curriculum includes advanced content in concept and theoretical formulations and testing, theoretical analyses, advanced nursing, supporting cognates, and in-depth research. The culminating requirement for the degree is the completion and defense of the doctoral dissertation. In 2008, 116 research-focused doctoral programs existed in 42 states (AACN, 2009c), awarding degrees to an average of 35 students per year from 2004 to 2008 (AACN, 2009a).

Pathways of Nursing Education

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() History of Nursing Education in the United States

History of Nursing Education in the United States

DIPLOMA PROGRAMS

BACCALAUREATE DEGREE EDUCATION

Accelerated BSN Programs

RN-BSN Track

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

ASSOCIATE DEGREE EDUCATION

MASTER’S DEGREE EDUCATION

RN-MSN and Nonnurse Master’s Entry Options

Dual Degree Programs

Clinical Nurse Leader Program

DOCTORAL EDUCATION

Research-Focused Programs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pathways of Nursing Education

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access