Chapter 2 Partnership working: the key to public health

Introduction

The idea of working in partnership is a recurring theme in health care. Twenty-five years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO 1978) declared that ‘people have a right and a duty to participate individually and collectively in the planning of their health care’, inferring that health professionals needed to establish a partnership with clients based on their participation and involvement.

It has been suggested that initiatives fostering partnership with parents and personal self-reliance may be more effective in improving child health than much of the routine work done by health visitors (Goodwin 1991). The ‘new nursing’ also emphasises the importance of the relationship of the patient with the nurse for the improvement in health outcomes (Salvage 1990). The health promotion literature identifies the worker–client relationship as key to changes in producing healthier lifestyles (Tones & Tilford 2001). In psychotherapy there is evidence to suggest that therapist characteristics and the client relationship are major predictors of outcome (Martin et al 2000) and this may be true for all other areas of health care, where effective communication is related to diagnostic accuracy (e.g. Papadopoulou et al 2005), treatment adherence, staff stress, and physical and psychological outcomes (e.g. Davis & Fallowfield 1991). In Child and Adolescent Mental Health too, the therapeutic relationship is associated with positive outcomes (Green 2006, Shirk & Karver 2003). A recent paper from America also showed that the patient’s perception of his/her relationship with the general practitioner was associated with a smaller risk of health status decline (Franks et al 2005).

The idea that the relationship is important to health outcomes is echoed in the work of Hall and Elliman (2003) who suggest that what works in terms of child health promotion programmes are: 1) that staff have the time and skill to establish a relationship of respect and trust with families and 2) that there is a sustained high quality and quantity of input and sufficient continuity to develop a relationship with the individual client. This may imply the need to commence a professional relationship during pregnancy rather than after the child is born. Almond (2001) found that positive health outcomes were reliant on the ability and skill of the health visitor to develop a positive relationship with the client. Tones and Tilford (2001) also argued that self-esteem, control and self-empowerment are all necessary features of health, and it would, therefore, seem evident that health visitors and other public health practitioners should have the skills to enhance these characteristics in their clients.

In spite of the importance of communication and relationship building, expertise of this type has been neglected in early preventive approaches, including health visiting. However, in recent UK policy documents there has been some acknowledgement of the importance of the relationship, not only with the client for healthy outcomes, but also between agencies. For example, the whole of chapter four of Every child matters: next steps (DfES 2004) is devoted to interagency partnership and collaborative working. The legislation that followed, the Children Act (2004), puts into place ‘robust partnership arrangements to ensure public, private, voluntary and community sector organisations work together to improve outcomes’ for children (p. 13). This acknowledges that at an organisational level working in partnership is effective in producing healthy outcomes. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), too, requires registrants on the Community Public Health part of their register to be able to ‘develop and sustain relationships with groups and individuals with the aim of improving health and social wellbeing’(NMC 2004). This does not specify the kind of relationship that might be helpful, nor does it state how it is related to the aim of improving health and social wellbeing. We would argue that, at whichever level it operates, partnership working requires good inter-personal relationships, developed through the skills and qualities required for good communication.

The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (Children’s NSF) requires services to: ‘give children, young people and their parents increased information, power and choice over the support and treatment they receive, and involve them in planning their care and services’ (DH 2004, p. 9). There is also some importance placed upon working in partnership with children throughout the document with emphasis upon ensuring that ‘children and young people’s voices are heard and they are involved in the design and delivery of services’ (p. 8). Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) have a duty to ensure that the Child Health Promotion Programme is ‘delivered in partnership with parents to help them make healthy choices for their children and family’ (p. 31). It appears to acknowledge that the relationship that is established is about empowerment through the giving of information and choice.

The common core competencies and skills of the NSF are to include effective communication and engagement (listening to and involving children and working with parents, carers and families) (p. 115). Listening to parents is also identified as one of the most effective ways of improving support services for them (p. 84) and is given a high priority throughout the document. Although the inclusion of the need for effective communication and engagement is to be commended, the details of the skills, apart from listening and the personal qualities involved in this, seem to be omitted. The NSF itself acknowledges that its implementation is dependent upon having an adequately resourced, trained and motivated workforce. However, we would argue that without the skills to work in partnership little will be accomplished.

It has been suggested that management may not construe the forming of partnerships as ‘real work’ (Elkan et al 2000b) and researchers have called for further studies to ‘demystify health visitor/client relationships in order to identify those aspects of the relationship that enable positive health outcomes’ (Elkan et al 2000a). Although there is evidence that home visiting programmes can be effective, the effects are generally small and there are many studies that have shown no effects whatsoever, as discussed by Gomby et al (1999). An implication of this is that we need to know the effective ingredients and the processes involved, yet there is little information about either. This arises both from the absence of adequate research into the processes, but also because of the lack of adequate theory. Few interventions are based on explicit theory, and those that are describe mechanisms to do with children’s development (e.g. parent–child interaction) and almost always ignore the equally important issues to do with the parent–helper interaction and the processes related to this.

Box 2.1 shows the kind of features that are suggested as ingredients of successful home visiting programmes. However, these do not elucidate the processes involved and fail to take account of the all-important relationship between the parent and home visitor.

Family partnership model for health and wellbeing

Given the urgent unmet mental health needs of children and parents in the population, existing service difficulties, current policy directives and the requirement for process research, the need for a model or theory of the processes of helping has never been greater. The Family Partnership Model has been developed over many years to meet this need (Davis 1993, Davis et al 2002a). It is intended as an accessible guide to the processes involved in helping families for all potential helpers, to enable their practice, and as the basis of system design and training. The overall aim has been to provide an explicit, relatively simple and therefore usable understanding of the various aspects of the process of helping and to develop an associated and effective training programme that will increase workers’ understanding and their skills in relating to and helping families.

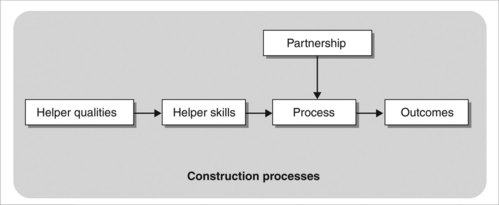

The model is presented in Figure 2.1 as a set of five interconnected boxes within a rectangle. Each of the boxes and the rectangle represent a small number of related theoretical points. The model is intended to suggest that helping can be seen as a set of steps, stages or tasks (the Process box), which are required to produce a set of designated changes (the Outcomes box). It is assumed that the process starts with the establishment of a relationship between the client and practitioner and that there is a need to define the nature of the relationship (the Partnership box) that will be most effective in facilitating the process and hence achieving the outcomes. To enable a partnership relationship and, therefore, the process as a whole, it is further assumed that the practitioner must have a small number of basic human characteristics (represented by the Helper Qualities box) and a larger set of communication skills (designated by the Helper Skills box) by which these qualities may be demonstrated to the client. These interconnected boxes are encompassed in a rectangle intended to represent an overall model of human functioning that sees people as though they were scientists attempting to understand/anticipate the events of their world and to adapt effectively. We will outline the theoretical points encompassed within each of the boxes and the rectangle in turn below, beginning with the outcomes.

Outcomes of working in partnership with clients

To work effectively, it is argued that potential helpers need to be explicit about the changes they are attempting to produce. The outcomes suggested within the Family Partnership Model are intended to offset a narrow specialist focus and to represent a much more holistic view of people as thinking, feeling beings always operating within a social context. The outcomes are shown in Box 2.2 and are discussed below.

To do no harm

Mitcheson and Cowley (2003) found that using a health needs assessment tool meant that client participation was reduced and professional expertise emphasised so that clients were disempowered. The relationships that health visitors have with clients are complex and their professional power may inhibit the exercise of their supportive role particularly in the field of domestic violence, so there is considerable need for practice development in this area (Peckover 2002, 2003).

What parents say they want is someone who will listen to them. In a recent paper, tellingly called ‘Someone to talk to who’ll listen’, Attride-Stirling et al (2001) asked parents and adolescents what would deter them from using services related to psychosocial wellbeing and what would encourage them to do so (see Box 2.3). Overall findings indicated that parents needed to be valued and understood, treated as capable human beings and to be facilitated in their role as carers.

It is clear that harm can be done by practitioners who, though well meaning, may not listen to parents, who as a result may feel disempowered. This will undoubtedly affect the clients’ access to services as previous bad experiences with professionals may mean that they are reluctant to engage with services that may potentially be of help to them and their children (Barlow et al 2005). Practitioners must attempt to make families’ experiences of being helped highly respectful and closely attuned to the needs of the family, and not unpleasant and distressing. At all times the practitioner should try to ensure that clients feel completely involved in the process, and that their views are important and that they are in control. In this way harm will be minimised, as help will be sensitive to their explicit needs.

To help clients identify, clarify and manage specific problems

This requires sensitive exploration by the practitioner to help clients express what is relevant to them and their circumstances. It might mean discussion of issues pertaining to themselves, their children or their family generally, as they all may be closely related. Problems that are raised may be beyond the practitioner’s expertise, and he/she will need to acknowledge this and help clients to become clearer about the problems themselves. It also enables the worker to gain a clearer insight into the client’s circumstances and to seek out the most relevant and appropriate source of help for the client if this is necessary.

To facilitate social support and community development

Social support has been found to be health enhancing (Oakley 1994). Therefore a major aim of working with clients should be to build on and enhance existing social support networks. Relationships between parents might be an important focus for the work but not to the neglect of other potentially supportive relationships with extended family, friends, neighbours and communities.

Helping process

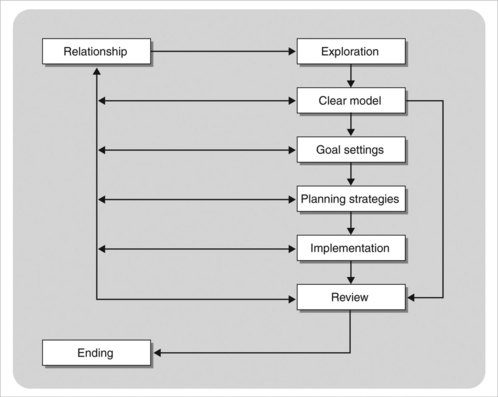

In order to be as effective as possible in helping anyone, all professionals should have a clear and explicit understanding of the process of helping. In the Family Partnership Model this is conceptualised as a simple series of eight steps, tasks or stages beginning with the establishment of a relationship between the client and the professional (see Fig. 2.2). It is assumed that the steps are sequential, with each subsequent stage dependent to a large extent upon the progress made in relation to the tasks preceding it. However, some clients may not need to progress through all the steps; it may be enough for them to explore issues that they have, come to a clear understanding of what they are about and then continue on their own without the need to involve the practitioner in any subsequent steps. As indicated in Figure 2.2 there may be a need to back-track to previous stages as continuing exploration brings into question conclusions drawn at previous stages. Of course, where there are multiple problems it may be necessary to loop through the whole process a number of times. We will now consider each of the steps in turn.

Exploration of needs, problems/issues

The aim of this stage is for the client and practitioner to develop a clearer understanding of the problems and needs of the individual, child and/or family. The extent to which this happens is dependent upon the quality of the relationship that develops between them. The task for the practitioner is to enable the clients to come to an understanding of the particular way in which they see (or construe) their problems or their needs in the context of their world more generally (Kelly 1991). This can be done quickly when all that is necessary is for a client to have the opportunity to talk and self-reflect in order to gain a greater insight into his/her needs and to change accordingly. Here the practitioner’s role will be to listen carefully, respecting the client, giving what Rogers called ‘unconditional positive regard’ (Rogers 1959). However, in more complex situations exploration may need to be more detailed. Here the skills of the practitioner in attentive and active listening will be of paramount importance to the development of a shared picture of the client’s needs. Throughout the process the practitioner will be trying to see the situation through the eyes of the client, while at the same time generating his/her own view of the situation to allow for possible alternatives for comparison at a later stage. It is interesting to note that in a study of vulnerable women who chose not to take up the offer of an early intervention service in Oxford, one of the reasons given was differences in professional and lay perceptions of vulnerability and need (Barlow et al 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree