Chapter 4 Parenting and family support: a public health issue

Introduction

Public health can be defined as, ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through organised efforts of society’ (Acheson 1998). Health visitors have a long history of working with families (Malone 2000) and have always seen their work as having a public health focus, although this has not always been acknowledged. The government-sponsored health visitor development pack defines the public health role of the health visitor as working through a continuum with individuals, families, groups and communities (Department of Health (DH) 2001). Families are the basic building blocks of our society or, in Bronfenbrenner’s (2005, p. 260) words, ‘the heart of our social system’ into which children are born and parented. Supporting families is crucial to enabling parents to nurture their children into mature, emotionally secure adults capable of initiating and sustaining their own relationships and meeting their own personal potential. This will undoubtedly have a positive impact on communities and society as a whole. However, parents’ efforts need to be complemented by action at a community level so that families feel supported by an environment where they can ask for help when they meet with difficulties.

Family and parenting support

What constitutes family and parenting support?

The term family support, when used within UK culture, can immediately rouse ideas about responding to problems and it is a common misconception to assume that inadequacy must exist if support is required. Within health and welfare services, The Children Act (1989) particularly lent credence to this view with its emphasis on the implementation of family support becoming synonymous with identified need. This legislation required local authorities to respond to a child as deemed in need and make available ‘family support’ to compensate for that need. Arguably this paved the way for the undesirable identity of family support that resulted from associations with neediness and inadequacy. This history, however, distorts perceptions and blinds us to the full extent of family support and thereby an understanding of it not just as a response system, but also as a fundamental component of a healthy society that actually needs to exist to maintain human development.

In order to appreciate what constitutes family support it is perhaps first helpful to consider what we understand of the modern family and hence parenting roles. Bronfenbrenner developed a bioecological understanding of human development, where environment plays a part in person development. He explains in a recent edited collection (Bronfenbrenner 2005) that there now exist new family forms that operate in an era where the family retains moral and legal responsibilities for children, but often lacks the opportunity to do the job properly. This, Bronfenbrenner argues, is due to the changed conditions of life, where children and parents spend little time together and instead each is in the company of peers. Indeed, current political drives to encourage increased paid employment (HM Treasury & Department for Work and Pensions 2003) is being supported by strategies that will extend the school day with the provision of breakfast and after school clubs (HM Treasury 2004b), where parents and children will continue to spend more and more time in their separate worlds. The existence of economic migration, secular adult partnerships, young motherhood and longer life span are some of the influences affecting the contemporary family that exists in various sizes, gender, ethnic and age combinations. With change comes an altered parental role where, for example, the loss of one parent may force the other to become breadwinner and carer, or, indeed, the loss of both parents may bring grandparents back into primary caregiver roles for children. Such situations exist with or without different types of family support and as Sheppard and Gröhn (2004) found, some have become so much a part of day-to-day existence that they are in danger of not being properly recognised as support. Moreover, the giver and receiver of support may have very different views about what and when it is needed and what purpose it is primarily serving.

Family support can be easily misunderstood, especially when it is so well integrated into daily patterns and, sadly, may only be recognised when it disappears. Clarity is needed to avoid what Quinton (2004) describes as never-ending circles of discussion on the topic and help with this comes from Ghate and Hazel’s (2002) study of parents’ experiences when living in economically harsh circumstances. They identified a three-fold model of social support comprised of:

This model fits with Bronfenbrenner’s notion of human ecology (Lerner 2005), which identifies the existence of social structures, sitting within one another as if nested like Russian dolls. Each nested structure is influenced by and, indeed, influences the other. When applied to Ghate and Hazel’s model, the informal support is nested around the immediate environment of the person. Semi-formal supports are an extension of informal support, but have more order to them. Within the model, semi-formal support influences the personal social network used by the person as opposed to the person directly. Likewise, formal support structures organised by statutory and officially sanctioned agencies operate as part of public policy and culture shaping the environment within which community-organised activ-ities (semi-formal structures) take place. Thus, each affects the other and trickles down to influence the individual at the centre of the nest.

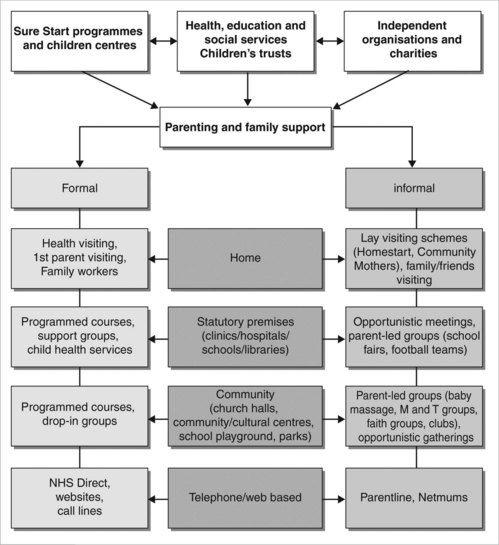

In recent years there have been major initiatives introduced by government to address family needs and in particular support child development and child health (Department of Health 2004, Department for Education & Skills 2004a). This includes the Treasury’s increased investment in the delivery of Sure Start programmes and Children’s Centres. Those bidding to secure funding for these in-itiatives need to demonstrate how new programmes will not only work alongside statutory services, but also in partnership with the local community to develop supportive networks for vulnerable children and families. Changes of this kind have influenced a tide of interest in parenting and with greater financial resources there has been growth in support facilities at various levels. An illustration of the diversity of arrangements is provided in the flow chart shown in Figure 4.1. Like Ghate and Hazel (2002), we identify existence of formal and informal support systems, but particularly draw attention to their coexistence through shared settings, which include intimate home environments, public community venues and virtual spaces accommodated by information technology and media facil-ities. Working alongside statutory service provision provided by professionals from health, education and local authority services, some are organised as part of Children’s Trusts (Department for Education & Skills 2003), Sure Start programmes (Department for Education & Employment 1999), Children’s Centres (Department for Education & Skills 2004b), and other independent bodies, operating with perhaps a national charity (e.g. Barnardos, Homestart & NSPCC) or with a local perspective (e.g. Ferries & Port Sunlight Family Groups in the North-west of England, Enfield Parents Centre in North London, Parent Network in Caerphilly, the Parents Advice Centre in Belfast and the Aberlour Child Care Trust, which has a number of strands to its work, but is funded through local authorities to provide family centres in Scotland).

Figure 4.1 Formal and informal parenting support across community settings

(from Bidmead & Whittaker 2004)

The purpose of the flow chart is to highlight the multi-faceted nature of parenting education and support, and the inextricable links between formal and informal care structures. The parent who meets others through attending a formal group at the health centre may on other occasions meet these same people opportunistically. In addition, he or she might use self-directed parenting resources for advice by regularly reading the popular press, watching the latest parenting television programme or by ‘logging-on’ to parent advice websites for information. Parenting as a source of media entertainment has grown out of all proportion in recent years (Brooks 2005, Crawford 2005, Woods 2005). The point is that each person accessing formal interventions delivered by professionals will also be exposed to less formal ideas, advice and explanations about parenting whether through personal social networks or the popular media. Suggestions offered about individual experiences could be perceived as criticism or praise and hence could either undermine or encourage a willingness to commit to formalised programmes of education and/or support. This means that to understand any local parenting and family support service there needs to be an appreciation of the wider community context because the unpredictable features of a community could be important determinants in the success of formalised strategies.

Why family and parenting support are a necessity for family health

Bronfenbrenner, in article 18 of his edited collection, reintroduces his 1988 paper on ‘Strengthening family systems’. Through the theme of caring, he uses the analogy of the heart and the body to describe the importance of the family to a society to assert the need for nurturing the family in order to keep society healthy. This perspective recognises that the development of a child will be influenced not just by the immediate family, but also by the community within which the family is located.

Community factors to some extent determine the manner and organisation of routines within the family. These factors include educational and employment opportunities that will shape the economic status of the family, which in turn impact on the availability of material resources important for maintaining health. Equally, beliefs held within the family will influence what goes on within the community. For example, parents’ perceptions about personal safety in the local community may influence their decisions about those routine activities that have a bearing on how and whether children socialise with other community members. Activities can include walking to school, playing outside or joining clubs. Thus, the two are closely connected. For Buchanan (2000), Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective offers a helpful way of understanding how the impact of family disadvantage on child health can be minimised through the artificial introduction of protective factors in the community setting. Examples include the availability of school milk and fruit for physical health or home-visiting play workers for child psychological health when mothers are postnatally depressed. Both support the parenting role and offer some level of compensation for either impoverished childhood diets or social interactions with adult caregivers.

Compensatory factors such as these are presumed to be important for the generation of resilience and reducing vulnerability when exposed to challenges later in life (Werner 1995). Parenting, because of its ability to influence new directions and experiences in a child’s life, then becomes one of the most significant means of affecting both resilience and vulnerability. The ability to parent and do so sufficiently is an ability to positively influence the health of children and thereby the next generation of adults. When understood in this way, parenting can be recognised as an important public health activity.

Stewart-Brown (2000) also builds on Bronfenbrenner’s work and helps explain the connection between parenting and health through the development of the wellbeing model, setting the emotional wellbeing of children and adolescents centre stage. The model presents a flow of relationships between parents and their children who grow into young adults facing new social situations in communities and workplaces. In Stewart-Brown’s view, healthy parenting involves showing respect, empathy and genuineness to growing children, who are then capable of learning how to appropriately relate to others and face challenges in adult life.

This model sits comfortably beside a growing body of the life-course research demonstrating relationships between adult health, early family experiences (Bifulco et al 2002, Russek & Schwartz 1997, Sweeting & West 1995), and childhood socio-economic disadvantage (Davey Smith et al 1998, Galobardes et al 2004, Kuh et al 2002, Kuh et al 2004, Richards et al 2001). Indeed, Davey Smith and Lynch (2004) explain that many of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease (a significant problem for health care systems worldwide) are ‘socially patterned’ and are evident across the entire life course. This means that the risks accrue from pre-conception, antenatally and then through infancy and childhood, dependent upon the parental circumstances. Negative socio-economic circumstances faced by parents and hence their children, contribute to mechanisms of risk for vascular disease through the reinforcement of behavioural or biological pathways (Davey Smith & Lynch 2004). Childhood states listed as contributing to risks for such pathways include: the experience of sustained stress, poor diet, obesity and poor growth. Equally, childhood social experiences have a part to play in determining future outcomes impacting on:

Similarly, when placed with evidence illustrating the connection between social relationships and physical health (Brunner 1997, Chandola et al 2004, House et al 1988, Power et al 1996, Russek & Schwartz 1997, Whiteman et al 2000), the importance of emotional wellbeing to individuals, families and communities becomes increasingly apparent. So much so that emotional health (alongside mental health) is now identified as an integral part of the being healthy outcome within the Every Child Matters: Change for Children programme (Department for Education & Skills 2004a).

The unpleasant consequences of early socio-economic disadvantage have been important drivers behind the development of the current Every Child Matters: Change for Children programme. There are good reasons for this, as research studies continue to reveal the damaging effects of poverty on children (Attree 2004) and parents (Attree 2005, Ceballo & McLoyd 2002). Being poor matters to children as it places an extra strain on family life. Nurturant parenting is compromised and the benefits that would normally be derived from strong social ties in a community are reduced (Ceballo & McLoyd 2002). Being parented and then becoming a parent in poor circumstances introduces a cumulative effect that limits the availability of material resources otherwise accessible through social networks and, therefore, the capacity for social ties to compensate for economic disadvantage (Attree 2005). Despite this, social relationships and the informal supports derived from these do have a crucial part to play in the wellbeing of children and parents (Attree 2004, 2005, Cochran et al 1990). Cochran et al (1990) explored the nature, purpose and value of social networks for parents and children in some detail within an international programme of research across four, Western, industrialised nations. Here they highlighted processes of social exchange, comparison, socialisation, care giving, modelling and stress buffering that provides children and their parents with rich learning opportunities. Outcomes derived from such processes included the chance to develop skills in respectful communication with others and be exposed to what Bandura (1995) would identify as the positive sources of self-efficacy. These include vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and a chance to practice and master new behaviours. However, it is argued that because informal systems of support can be so fragile (Llewellyn & McConnell 2002), formal social support needs to be carefully balanced and take account of existing strengths within families and communities (Kirk 2003).

A decade ago, Oakley et al (1994) argued that social support was in fact, health promoting and particularly important to those who are more at risk from adverse life-events through living in stressful circumstances with little income, poor housing, and a lack of supportive relationships. It is in these circumstances that the ‘stress buffering’ effects that Cochran et al (1990) mention can come into force, by moderating the impact of difficult material circumstances. This is achieved by a strengthened capacity to manage challenges as a result of improved knowledge and information about external resources and a greater sense of self-esteem and confidence fuelling a personal inner resource to act. These internal and external resources are regarded as resources for health (Cowley & Billings 1999) and if harnessed through social support should, indeed, be helpful mechanisms that enable parents to promote the health of their children.

More recently, Oakley has with colleagues tested these ideas to determine the effectiveness of social support when offered to women living in areas of deprivation. This research involved a three armed randomised controlled trial located in two London boroughs (Austerberry et al 2004, Turner et al 2005). The trial compared a support health visitor (SHV) service, community group support (CGS) and standard services, with the last acting as the control. The social support provided by the SHV involved monthly supportive listening visits whereas the standard service involved only one routine home visit during the early postnatal period and thereafter women could only access health visitors through child health clinics. The CGS arm of trial offered women contact with one of eight locally based community groups that were predominantly staffed by volunteers. The most successful arm of the trial was the SHV intervention, which provided women with a sense that they were being listened to and an opportunity to discuss personal issues. These women also reported less anxiety about their parenting, had fewer concerns about their child’s development and, interestingly, altered their style of health service use. The change was in a manner that the authors felt was more favourable (Austerberry et al 2004) and in keeping with seeking advice concerned with maintaining health as opposed to managing illness. The main challenge for the CGS arm was the engagement of women in the activities offered by the community groups. One in five women claimed that their non-use of services was because they were too busy or had a full social life. For the small proportion (19%, 35) that did use the CGS some positive views were expressed about the value of getting out and meeting other parents, but equally attention was drawn to the subtle features of the group sessions (e.g. sense of disorganisation or missed opportunities to welcome newcomers), that can act as turn-offs and feed reasons for non-attendance in the future (Turner et al 2005). A clear message from this study is that the provision of social support services does not guarantee that needs will be met, especially if service use requires special efforts on the part of the parent. Involvement in community groups essentially involves making some level of investment, such as time, personal organisation to get there and not least an ability and willingness to engage socially with others. Social support offered by health visitor home visits asks less of the parents before they have witnessed the investment made by the health visitor. This is perhaps, therefore, a more conducive means of encouraging more marginalised parents to make better use of social support services that can evolve as important sources of emotional and practical help. Llewellyn and McConnell (2002) discuss the significance of parenting social support with special reference to parents with learning disabilities, illustrating how these parents are especially vulnerable if supportive relationships fail.

Children living in families with insufficient social support will feel the effects through the social and, thereby, educational opportunities available to them (Cochran et al 1990), which shape how they are socially programmed (Wadsworth 1999). Social programming results from the experiences that infants and children are exposed to through family life. This includes the family circumstances (economic prosperity, educational opportunity) and family function (cohesion, accord and positive regard, parental self-esteem), which collectively impact on child educational attainment and opportunity to develop self-control and skills in managing one’s own behaviour. Wadsworth (1999) explains that these features of early social life generate vulnerability or resilience to subsequent life stressors. This is likened to Barker’s (1998) model of biological programming for fetuses in utero, infants and children when exposed to biological hazards, such as parental smoking, poor nutrition or early infection. These hazards interfere with subsequent maturation of cells and organs, and create vulnerability in adults if later exposed to biological stressors, such as a high-fat, -sugar and -salt diet, smoking or infectious disease.

The significance of parenting as a social programming activity can be realised in the evidence that is emerging from the previously acknowledged life course research and, in particular, that which illustrates the relationship between the quality of nurturing and nourishment provided during childhood years and the development of coping and competence skills in adult life (Bartley et al 1999). A recent addition to this body of work is the life course framework published by the Health Development Agency (Graham & Power 2004). This identifies pathways towards poor adult health originating from conception and right through childhood. What is evident is the powerful force parental disadvantage has on childhood and the expectations young people have of themselves as they enter adulthood.

Graham and Power (2004) indicate how children with limited social and educational opportunities have greater reason for investing in identities that do not require school achievements and, instead, sources of self-affirmation are found through identity with peers and family. In essence they become socially programmed to follow certain life patterns. These identities, Graham and Power (2004) explain, typically involve sexual relationships that result in early cohabitation and parenthood for females and other activities that offer instant excitement and interest that can involve young males in law breaking and criminal activities. If experienced, these factors become life limiting, impacting on a young person’s ability to manage new challenges in the education system and, later, the labour market. This may influence personal economic destinies and resilience or vulnerability to physical, mental and social stressors (Montgomery et al 1996). The secondary outcome from this unhappy chain of events is the self-perpetuating nature of such life patterns that tend to be repeated through generations if parental disadvantage is not addressed (Bartley et al 1999, Graham & Power 2004). Once more, future generations of parents are reliant on the scenarios played earlier on in their lives, since the task of parenting is learnt from the parenting previously received. Wilkinson (1999) identifies this cyclical situation as a disastrous recipe for health which, when combined with weakened social bonds, raises stress experiences and chronic anxiety. These states then act as precursors to other health-limiting behaviours, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, that increase the risk of coronary heart disease (Kuh & Ben-Schlomo 2004). The task then is to help children and young people become resilient to such life risks, by improving early social experiences.

Family and parenting support: impact on life trajectory from infancy

Both our physiological and psychological systems are developed in relationships with other people and this is never more true than in infancy (Gerhardt 2004). The intensity of interaction between a baby and its carers has enormous consequences for:

Infant brain development

Gerhardt (2004) describes the newborn baby as a seedling that develops strong roots and good growth if the environmental conditions are right. Babies are like seedlings because their physiological and psychological systems are unformed and very delicate. They are subject to stress responses that may be particularly prevalent where early experiences are problematic. These stress responses impact on brain development (Shore 2001). It is during the first months of life that the brain is at its most plastic and flexible, so that the baby can develop and fit into the world that he/she finds. This means that babies adapt to their environment in order to fit into their family, culture and community. The 100 billion brain cells with which a baby is born are not interconnected and most cannot function in isolation. They need to be organised into networks that require trillions of synapses between them. Although the development of these connections depends, to some extent, on genes, they also depend on early life events, particularly the early care and nurturing received from birth. Empathic care giving from an emotionally available caregiver, which is warm, affectionate, sensitive and attentive, providing patterned visual and auditory stimulation, particularly language, are critical if the baby is to achieve optimal brain development (Bee 2000). A serious lack of sensitive interaction in the early months will have long-lasting effects not only on infants’ cognitive abilities, but on their ability to form lasting relationships. This sensitive interaction is as essential for growth as a diet that is rich in essential nutrients. The rapid growth that takes place in the first 3 years of life are a crucial time where social interaction and environmental predictability maximise development. It is during this time that children grow in their abilities to think and speak, learn and reason, setting patterns that will last a lifetime and lay the foundation for their values and social behaviour as adults. The quality and content of the baby’s relationship with his/her parents or carers has an effect on the neurobiological structure of the child’s brain that will be enduring. Once the brain is developed it is much harder to modify (Balbernie 2004).

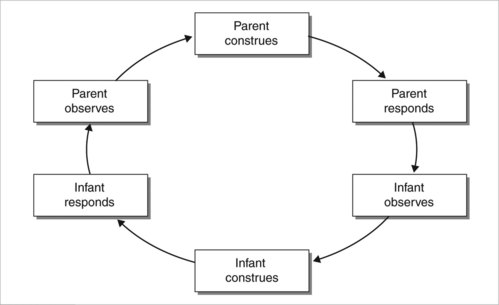

Figure 4.2 illustrates the cycle of interaction between the baby and his/her parents or caregivers. Both parent and baby watch each other and then try to make sense of what they see and hear or experience and respond accordingly. This is a mutual process, with both the parent’s and the baby’s behaviour or response determined by the understanding that they are able to make of the other’s actions. The experiences that the infant gains within this relationship then colours his/her anticipation of future relationships with others.

However, the difficult thing about this interaction is that the baby needs this care all the time. The baby needs a caregiver who is emotionally available, responsive and able to identify the baby’s needs. Problems that interfere with the interaction and the ability to respond appropriately may trigger a spiral in a downward trend. For example, when a mother is depressed and unable to respond sensitively to her infant, the baby comes to accept that his/her needs will not be met and will also act in a depressed way (Field et al 1988). The baby’s problems also seem to persist into later childhood (Murray 1992, Cooper & Murray 1998).

Gerhardt (2004) suggests that support for parents is crucial if they are to be ‘good enough’ caregivers. The tension that exists between the need to work and to be at home caring for the baby often leads women to make choices to do one or the other when, according to the evidence, they want to do both (Newell 1992). At home they may be isolated from social contact, leading to depression. At work they may be in a continual state of anxiety and guilt about the care of the baby. Neither choice seems beneficial. Both may lead to depression in either or both parents with consequences for their child’s emotional and physical wellbeing both in infancy and, as we shall see, in later childhood through into adulthood.

Child mental health, physical wellbeing and development

In 1999 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) carried out its first national survey of child mental health in the UK (Meltzer et al 2000). It found that almost one in ten 5- to 15-year-olds were facing handicapping emotional or behavioural problems (Meltzer et al 2000). The latest ONS survey (Green et al 2005) makes depressing reading, showing no change at all in the prevalence of mental ill health in children in this age group. Longitudinal evidence shows that many child psychiatric disorders persist well into adult life, increasing the risks for mental health problems and difficulties in social functioning. More working days are lost due to mental ill health than physical conditions (World Health Organization (WHO) 1998). For young people and their families, as well as for society as a whole, the cost of child mental health problems is high. Preventing, identifying and treating psychological disorders, therefore, not only reduces misery for suffers and their families, but improves the functioning of the working population.

In older children those with a mental health problem had a higher prevalence of:

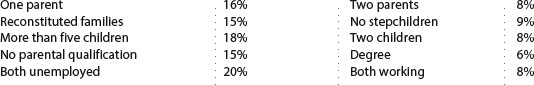

Other risk factors were also contributory factors to the prevalence of child mental health disorders. They were found to be more prevalent in lone families, reconstituted families where there were five or more children, where parents had no educational qualifications and where both partners were unemployed (see Table 4.1).

Worryingly, in an 18-month follow-up of the ONS survey children, it was found that many disorders and, in particular, conduct and hyperkinetic disorders, were persisting through childhood (Meltzer et al 2000). However, when a disorder-based approach is taken, as in the ONS study, the existence of problems that do not constitute a disorder may well be disguised. It was for this reason that a different approach was taken in Southwark, in London, where a random survey of 253 children 0–16 years in three GP practices was conducted to elicit problems and risk factors for mental health difficulties in one of the most deprived areas of the UK (Davis et al 2000). Semi-structured interviews were undertaken at home by psychologists trained in the methods to elicit problems and risk factors that were judged against predetermined criteria for severity. For children younger than 14 years, the interview was conducted with the main carer, who was mainly the mother. A list of 47 possible problems were identified, e.g. generalised anxiety, phobias, truancy, depressed mood, inattention, overactivity, eating problems, poor temper control, stealing.

A similar study of 473 children aged 0–17 years recruited from seven GP practices in Lewisham, another London borough, found that between 20% and 37% of children had three or more significant problems (Attride-Stirling et al 2000). Approximately 48% had a least one psychosocial problem and 50% had three or more risk factors for child mental health problems. This indicated that every other child had a quite serious problem and one in five children had a group of severe problems. As many as one in two families were struggling with difficulties related to the development of psychosocial problems in their children. Whilst limited to one London borough, the Lewisham example is useful because it provides an insight into the most common problems. For 5- to 10-year-olds these included:

Adult mental and physical health problems later in life

In the previous discussion of unhelpful parenting effects in childhood, it is self-evident that many of the consequences felt in childhood have the potential to also manifest as adult experiences. In particular, early impaired psychological functioning accumulates, triggering patterns of social dysfunction, an inability to cope with stress and a predisposition towards enduring mental illness as well as impaired physical functioning.

Russek and Schwartz (1997) showed, in a study obtained from undergraduates at Harvard University, that perceptions of parental caring predict the health status in mid-life. In the early 1950s, initial ratings of parental caring were obtained from a sample of healthy Harvard undergraduate men. During the 35-year follow-up investigation, detailed medical and psychological histories and medical records were obtained. The results showed that in mid-life those suffering from illnesses, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, duodenal ulcers and alcoholism, had perceived their parents to have a significantly lower rate of parental caring items (i.e. loving, just, fair, hardworking, clever, strong) while they were in college. ‘This effect was independent of the subject’s age, family history of illness, smoking behaviour, the death and/or divorce of parents, and the marital history of subjects’ (Russek & Schwartz 1997, p. 144). Furthermore, 87% of subjects who rated both their mothers and fathers as low in parental caring had diagnosed diseases in mid-life, whereas only 25% of subjects who rated both their mother and fathers high in parental caring had diagnosed diseases in mid-life. They concluded that:

Family and parenting support for a stronger economy

The economic importance of parenting can be understood at a number of levels. Within the plans laid out in the government’s Child Poverty Review (HM Treasury 2004a), there is an explicit concern to move parents, and especially those separated from partners, into positions of employment where they can generate income for themselves and their children. This goal serves the political aspirations of delivering income directly into the households of materially deprived children, and reducing the number of children living in workless households. This later point could be of value for normalising the experience of working for an income especially in families where the decline of local industry has created a cycle of unemployment across generations. By working and generating income, parents will be contributing to the primary wealth-creating sector (Mustard 1996).

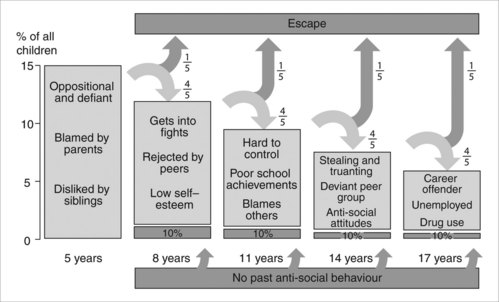

In situations where parents reject government efforts to get them into work and instead adopt homemaker roles that include child care, they become classified by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN/ECE) as economically inactive, but can at least be counted as providers of non-paid services (Hantrais 2004). Despite this classification it is argued that parents working effectively to improve family functioning do continue to contribute to a nation’s economy even if indirectly, by supporting working partners or by nurturing children to grow into well-adjusted, socially competent adults. In these circumstances, parents will be contributing to what Mustard (1996) refers to as the secondary wealth-creating sector that affects the quality of the social environment within which the primary sector operates. The central importance of this role for the rest of society is often only appreciated when things go wrong and ineffectively parented children fail to develop the personal self-control necessary for avoiding a tendency towards anti-social behaviour and accident-prone risk-taking behaviour (Pulkkinen & Hamalainen 1995). Indeed, there is a need to recognise the potential bearing that positive parenting practices have on some of the externalities, namely anti-social costs and lost days from the workforce, that Wanless (2004) highlights as affecting health service provision.

The financial costs to health services from treating behaviourally disordered children are highlighted in research published by Guevara et al (2003). The evidence here indicated how children with behaviour disorders, like those with chronic physical conditions, made greater use of office-based consultations and accident and emergency services and even more use than children with physical disorders of prescribed medication. In a UK study, Scott et al (2001) also confirm these health service costs through their follow-up of children with anti-social behaviour, where the existence of conduct disorder was the greatest predictor of future costs. This research is referred to within the earlier Every child matters, government Green Paper (Department for Education & Skills 2003) and the pathway of consequences from not dealing with childhood oppositional and defiant disorders is clearly illustrated (Figure 4.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree