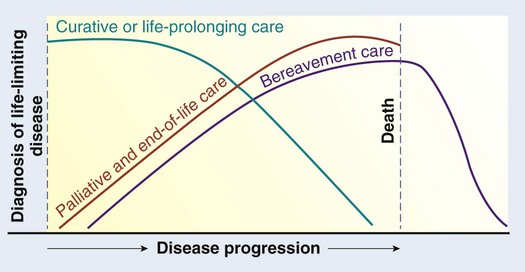

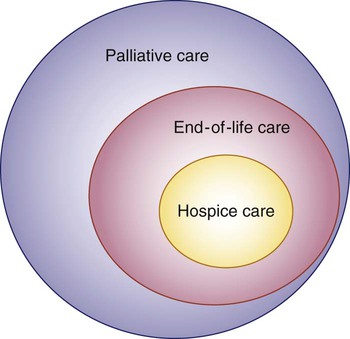

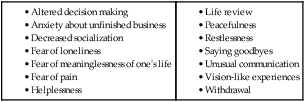

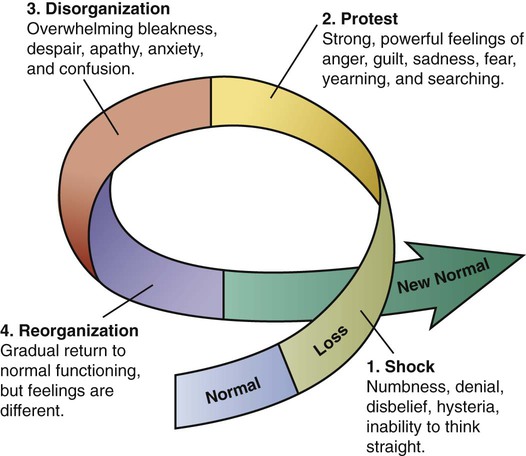

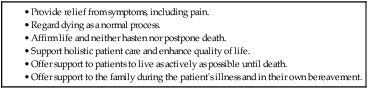

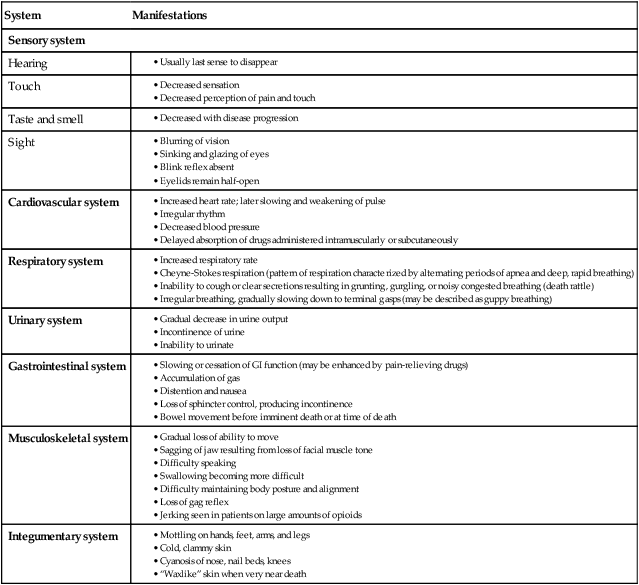

Chapter 10 1. Discuss the purpose of palliative care. 2. Describe the purpose of and services provided by hospice. 3. Describe the physical and psychologic manifestations at the end of life. 4. Explain the process of grief and bereavement at the end of life. 5. Describe the nursing management for the dying patient. 6. Examine the cultural and spiritual issues related to end-of-life care. 7. Discuss ethical and legal issues in end-of-life care. 8. Explore the special needs of family caregivers in end-of-life care. 9. Discuss the special needs of the nurse who cares for dying patients and their families. Palliative care is any form of care or treatment that focuses on reducing the severity of disease symptoms, rather than trying to delay or reverse the progression of the disease itself or provide a cure. The overall goals of palliative care are to (1) prevent and relieve suffering and (2) improve quality of life for patients with serious, life-limiting illnesses (Fig. 10-1). Specific goals of palliative care are listed in Table 10-1. TABLE 10-1 Adapted from World Health Organization: WHO definition of palliative care. Retrieved from www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families who face problems associated with life-threatening illness. Palliative care aims to prevent and relieve suffering by early identification, assessment, and treatment of pain and other types of physical, psychologic, emotional, and spiritual distress.1 Ideally, all patients receiving curative or restorative health care should receive palliative care concurrently. Palliative care extends into the period of EOL care; bereavement care follows the patient’s death2 (Fig. 10-2). To optimize the benefits of palliative care, it should be initiated after a person receives a diagnosis of a life-limiting illness, such as cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, or end-stage kidney disease. Ideally, the palliative care team is an interdisciplinary collaboration involving physicians, social workers, pharmacists, nurses, chaplains, and other health care professionals. Communication among the patient, family, and palliative health care team is important to provide optimal care. Patients receive palliative care services in the home and in long-term and acute care facilities. More recently, emergency departments and intensive care units (ICUs) have integrated palliative care into the delivery of care. Many institutions have established interdisciplinary palliative and hospice care teams.3 Palliative care often includes hospice care before or at the end of life (Fig. 10-3). Hospice is not a place but a concept of care that provides compassion, concern, and support for the dying (Fig. 10-4). Hospice exists to provide support and care for persons in the last phases of a terminal disease so that they might live as fully and as comfortable as possible. Hospice programs provide care with an emphasis on symptom management, advance care planning, spiritual care, and family support.4 Approximately 1.5 million patients every year receive services through hospice programs. About 42% of the patients who die in the United States are under the care of a hospice program.5 More than a third of all hospice patients are 85 years of age or older, and 83% are over 65. Of these patients, the most common diagnosis is cancer. Eighty percent of patients using hospice services are white.5 Currently the median length of stay in a hospice program is 21 days. Hospice care is provided in a variety of locations, including the home, inpatient settings, and long-term care facilities. Hospice care can be on a part-time, intermittent, on-call, regularly scheduled, or continuous basis. Hospice services are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to provide help to patients and families in their homes. The inpatient hospice settings have been deinstitutionalized to make the atmosphere as relaxed and homelike as possible (Fig. 10-5). Staff and volunteers are available for the patient and the family. A medically supervised interdisciplinary team of professionals and volunteers provides holistic hospice services. The hospice nurse plays a pivotal role in coordination of the hospice team.6 Hospice nurses work collaboratively with hospice physicians, pharmacists, dietitians, physical therapists, social workers, certified nursing assistants, chaplains and other clergy, and volunteers to provide care and support to the patient and the family. Hospice nurses are educated in pain control and symptom management, spiritual assessment, and assessment and management of family needs. To meet patient and family needs, hospice nurses need excellent teaching skills, compassion, flexibility, cultural competence, and adaptability. The decision to begin hospice care is difficult for several reasons. Frequently patients, families, physicians, and other health care providers lack information about hospice care. Some cultural/ethnic groups may underutilize hospice because of lack of awareness of hospice services, desire to continue with potentially curative therapies, and concerns about lack of minority hospice workers.7 Physicians may be reluctant to give referrals because they sometimes view a patient’s decline as their personal failure. Some patients or family members see it as giving up. Brain death is an irreversible loss of all brain functions, including those of the brainstem. Brain death is a clinical diagnosis, and it can be made in patients whose hearts continue to beat and who are maintained on mechanical ventilation in the ICU.8 Brain death occurs when the cerebral cortex stops functioning or is irreversibly destroyed. Since the development of technology that assists in supporting life, controversies have arisen over the exact definition of death. Questions and discussions have focused on whether brain death occurs when the whole brain (cortex and brainstem) ceases activity or when function of the cortex alone stops. In 1995 the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology recommended diagnostic criteria guidelines for clinical diagnosis of brain death.9 These criteria for brain death include coma or unresponsiveness, absence of brainstem reflexes, and apnea. Specific assessments by a physician are required to validate each of the criteria.8,9 The Institute of Medicine defines end of life as the period during which an individual copes with declining health from a terminal illness or from the frailties associated with advanced age, even if death is not clearly imminent.10 In some cases it is obvious to health care providers that the patient is at the end of life, but in other cases they may be uncertain if the end is close at hand. This uncertainty adds to the challenge of answering common questions the patient and family may ask, such as “How much time is left?” As death approaches, metabolism is reduced and the body gradually slows down until all functions end. Respiratory changes are common at the end of life. Respirations may be rapid or slow, shallow, and irregular. Breath sounds may become wet and noisy, both audibly and on auscultation. Noisy, wet-sounding respirations, termed the death rattle, are caused by mouth breathing and accumulation of mucus in the airways. Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a pattern of breathing characterized by alternating periods of apnea and deep, rapid breathing. When respirations cease, the heart stops beating within a few minutes. The physical manifestations of approaching death are listed in Table 10-2. TABLE 10-2 PHYSICAL MANIFESTATIONS AT END OF LIFE • Cheyne-Stokes respiration (pattern of respiration characterized by alternating periods of apnea and deep, rapid breathing) • Inability to cough or clear secretions resulting in grunting, gurgling, or noisy congested breathing (death rattle) • Irregular breathing, gradually slowing down to terminal gasps (may be described as guppy breathing) A variety of feelings and emotions can affect the dying patient and family at the end of life (Table 10-3). Most patients and families struggle with a terminal diagnosis and the realization that there is no cure. The patient and the family may feel overwhelmed, fearful, powerless, and fatigued. The family’s response depends in part on the type and length of the illness and their relationship with the person. Grief is a powerful emotional state that affects all aspects of a person’s life. It is a complex and intense emotional experience. In the Kübler-Ross model of grief, there are five stages11,12 (Table 10-4). Not every person experiences all the stages of grieving, and they are not always progressive in order. It is common to reach a stage and then go backward. For example, a person may have reached the stage of bargaining, and then revert back to the denial or anger stage. TABLE 10-4 Adapted from Kübler-Ross E: On death and dying, New York, 1969, Macmillan. (Classic) Another model of grief is the grief wheel (Fig. 10-6). After a person experiences the loss, he or she feels shock (numbness, denial, inability to think straight). Then comes the protest stage where a person experiences anger, guilt, sadness, fear, and searching. Then comes the disorganization stage where a person feels despair, apathy, anxiety, and confusion. The next stage is reorganization where a person gradually returns to normal functioning, but he or she feels different. The final stage is the new normal. Eventually the destabilization experienced in grief resolves and a normal state can began. However, because of the loss, the normal state is not the same as before. The challenge is to accept the new normal. Trying to go back to the “old” normal (which is not there anymore) is what causes a great deal of anxiety and stress. The manner in which a person grieves depends on factors such as the relationship with the person who has died (e.g., spouse, parent), physical and emotional coping resources, concurrent life stresses, cultural beliefs, and personality. Additional factors that affect the grief response include mental and physical health, economic resources, religious influences or spiritual beliefs, family relationships, social support, and time spent preparing for the death. Issues that occurred before the death (e.g., marital problems) may affect the grief response.13 Working in a positive way through the grief process helps to adapt to the loss.14 Grief that assists the person in accepting the reality of death is called adaptive grief, which is a healthy response. It may be associated with grieving before a death actually occurs or when the inevitability of the death is known. Indicators of adaptive grief include the ability to see some good resulting from the death and positive memories of the deceased person. Dysfunctional reactions to loss can occur, and the physical and psychologic impact of the loved one’s death may persist for years. Prolonged grief disorder, formerly called complicated grief, is a term used to describe prolonged and intense mourning. Prolonged grief disorder can include symptoms such as recurrent and severe distressing emotions and intrusive thoughts related to the loss of a loved one, self-neglect, and denial of the loss for longer than 6 months. Bereaved individuals with prolonged grief disorder may feel “stuck” and unable to move forward after the death of a loved one. It is estimated that one in five bereaved individuals experiences prolonged grief disorder. Those who experience prolonged grief disorder are at great risk for illness and have work and social impairments. Some studies suggest that prolonged grief disorder is less likely to occur after deaths in hospice compared with those in acute care settings.15 Assessment of spiritual needs in EOL care is a key consideration (Table 10-5). Spiritual needs do not necessarily equate to religion. Spirituality is defined as those beliefs, values, and practices that relate to the search for existential meaning and purpose and that may or may not include a belief in a higher power.16 A person may not be part of a particular religion but have a deep spirituality. Many times at the end of life, patients question their beliefs about a higher power, their journey through life, religion, and an afterlife (Fig. 10-7). Some patients may choose to pursue a spiritual path. Some may not. Respect an individual’s choice. Assess the patient’s and the family’s preferences related to spiritual guidance or pastoral care services and make appropriate referrals.16 TABLE 10-5

Palliative Care at End of Life

Palliative Care

Hospice Care

Death

End-of-Life Care

Physical Manifestations at End of Life

System

Manifestations

Sensory system

Hearing

Touch

Taste and smell

Sight

Cardiovascular system

Respiratory system

Urinary system

Gastrointestinal system

Musculoskeletal system

Integumentary system

Psychosocial Manifestations at End of Life

Bereavement and Grief

Stage

What Person May Say

Characteristics

Denial

No, not me. It cannot be true.

Denies the loss has taken place and may withdraw. This response may last minutes to months.

Anger

Why me?

May be angry at the person who inflicted the hurt (even after death) or at the world for letting it happen. May be angry with self for letting an event (e.g., car accident) take place, even if nothing could have stopped it.

Bargaining

Yes me, but…

May make bargains with God, asking “If I do this, will you take away the loss?”

Depression

Yes me, and I am sad

Feels numb, although anger and sadness may remain underneath.

Acceptance

Yes me, but it is okay

Anger, sadness, and mourning have tapered off. Accepts the reality of the loss.

Spiritual Needs