TYPE OF PAIN | PHYSIOLOGIC EVIDENCE | BEHAVIORAL EVIDENCE |

Acute | ♦ Increased respirations ♦ Increased pulse ♦ Increased blood pressure ♦ Dilated pupils ♦ Diaphoresis | ♦ Restlessness ♦ Distraction ♦ Worry ♦ Distress |

Chronic | ♦ Normal respirations, pulse, blood pressure, and pupil size ♦ No diaphoresis | ♦ Reduced or absent physical activity ♦ Despair or depression ♦ Hopelessness |

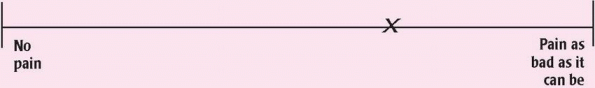

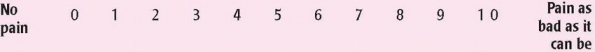

An older adult may not report pain and may metabolize and experience the effects of analgesic drugs differently than a younger patient. To assess pain in an older patient with cognitive dysfunction, use such cues as behavior (motor responses, facial expressions, crying) and physiologic changes (increased blood pressure and heart rate) in addition to self-reporting.

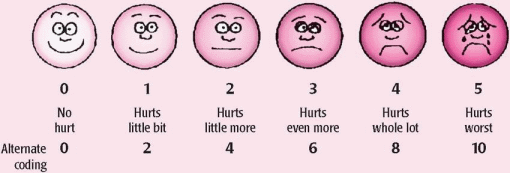

An older adult may not report pain and may metabolize and experience the effects of analgesic drugs differently than a younger patient. To assess pain in an older patient with cognitive dysfunction, use such cues as behavior (motor responses, facial expressions, crying) and physiologic changes (increased blood pressure and heart rate) in addition to self-reporting. Children metabolize drugs differently from adults and may experience the effects of analgesics differently. When assessing pain in a child, use verbal, numeric, or picture scales to help determine the child’s pain level in addition to direct questions. Also watch for behavioral cues (facial expressions, crying) and physiologic changes (increased blood pressure and heart rate) to help determine the child’s pain level.

Children metabolize drugs differently from adults and may experience the effects of analgesics differently. When assessing pain in a child, use verbal, numeric, or picture scales to help determine the child’s pain level in addition to direct questions. Also watch for behavioral cues (facial expressions, crying) and physiologic changes (increased blood pressure and heart rate) to help determine the child’s pain level.

|

|

□ Grimacing □ Moaning □ Sighing □ Clenching the teeth □ Holding or supporting the painful body area □ Sitting rigidly □ Frequently shifting posture or position □ Moving in a guarded or protective manner □ Moving very slowly □ Limping □ Taking medication | □ Using a cane, a cervical collar, or another prosthetic device □ Walking with an abnormal gait □ Requesting help with walking □ Stopping frequently while walking □ Lying down during the day □ Avoiding physical activity □ Being irritable □ Asking such questions as, “Why did this happen to me?” □ Asking to be relieved from tasks or activities |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree