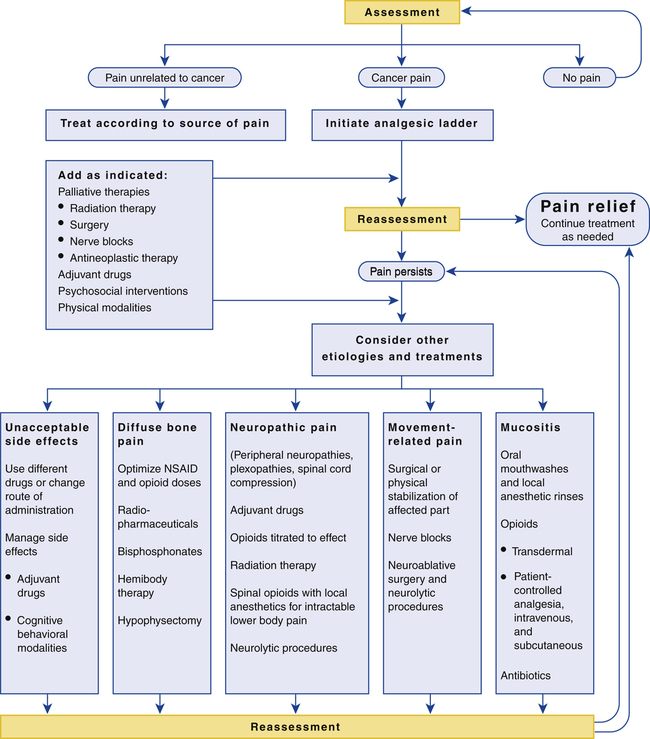

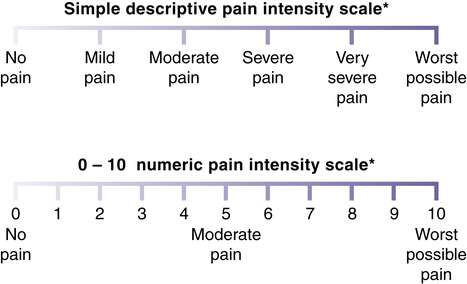

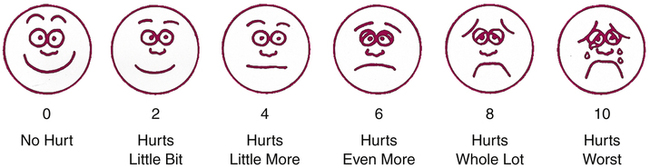

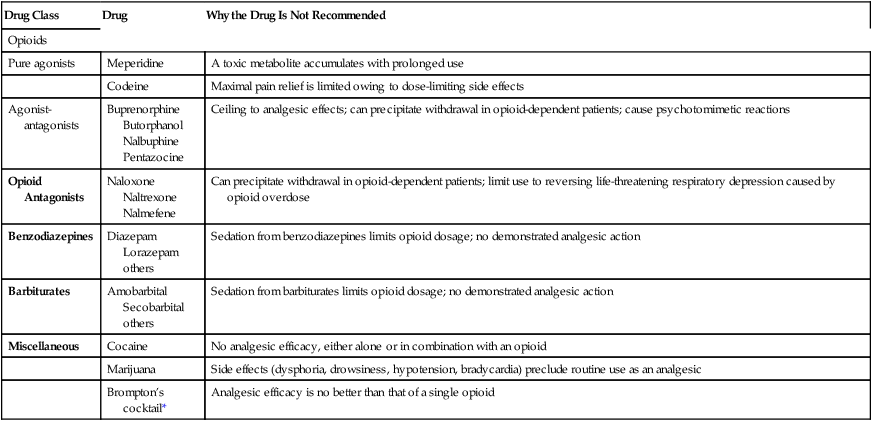

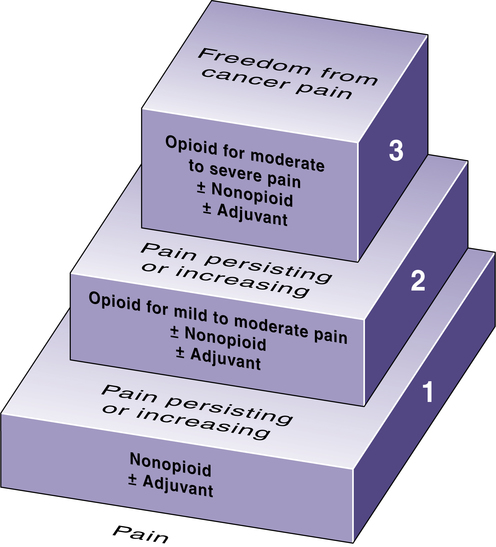

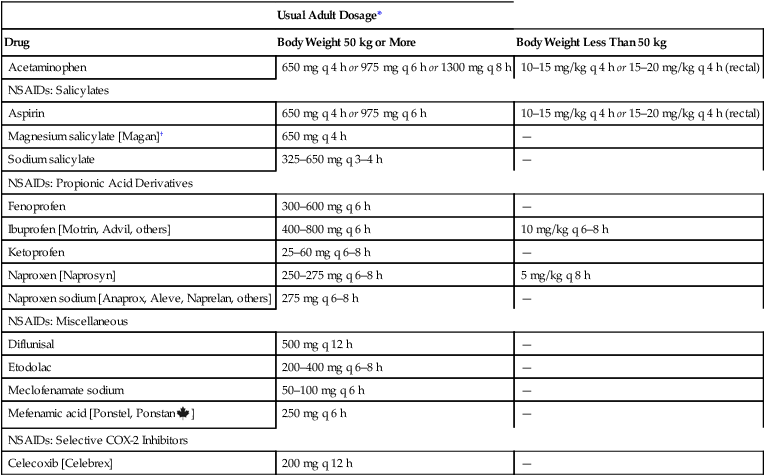

CHAPTER 29 Our topic for this chapter—management of cancer pain—is of note both for its good news and its bad news. The good news is that cancer pain can be relieved with simple interventions in 90% of patients. The bad news is that, despite the availability of effective treatments, pain goes unrelieved far too often. Multiple factors contribute to undertreatment (Table 29–1). Important among these are inadequate prescriber training in pain management; unfounded fears of addiction (shared by prescribers, patients, and families); and a healthcare system that focuses more on treating disease than relieving suffering. TABLE 29–1 Barriers to Cancer Pain Management Barriers Related to Healthcare Professionals Inadequate knowledge of pain management Poor assessment of pain Concerns stemming from regulations on controlled substances Fear of patient addiction Concern about side effects of analgesics Concern about tolerance to analgesics Barriers Related to Patients Reluctance to report pain Fear of distracting physicians from treating the cancer Fear that pain means the cancer is worse Concern about not being a “good” patient Reluctance to take pain medication Fear of addiction or being thought of as an addict Worries about unmanageable side effects Concern about becoming tolerant to pain medications Inability to pay for treatment Barriers Related to the Healthcare System Low priority given to cancer pain management Inadequate reimbursement: The most appropriate treatment may not be reimbursed Restrictive regulation of controlled substances Treatment is unavailable or access is limited Adapted from Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, et al: Management of Cancer Pain (Clinical Practice Guideline No. 9; AHCPR Publication No. 94-0592). Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1994. Management of cancer pain is an ongoing process that involves repeating cycles of assessment, intervention, and reassessment. The goal is to create and implement a flexible treatment plan that can meet the changing needs of the individual patient. The flow chart in Figure 29–1 summarizes the steps involved. Management begins with a comprehensive assessment. Once the nature of the pain has been determined, a treatment modality is selected. Analgesic drugs are preferred, and hence are usually tried first. If drugs are ineffective, other modalities can be implemented. Among these are radiation, surgery, and nerve blocks. After each intervention, pain is reassessed. Once relief has been achieved, the effective intervention is continued, accompanied by frequent reassessments. If severe pain returns or new pain develops, a new comprehensive assessment should be performed—followed by appropriate interventions and reassessment. Throughout this process, the healthcare team should make every effort to ensure active involvement of the patient and his or her family. Without their involvement, maximal benefits cannot be achieved. The importance of patient and family involvement is reflected in the clinical approach to pain management recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): B Believe the patient and family in their reports of pain and what relieves it. C Choose pain control options appropriate for the patient, family, and setting. D Deliver interventions in a timely, logical, and coordinated fashion. E Empower patients and their families. Enable patients to control their treatment to the greatest extent possible. Onset and temporal pattern—When did your pain begin? How often does it occur? Has the intensity increased, decreased, or remained constant? Does the intensity vary throughout the day? Location—Where is your pain? Do you feel pain in more than one place? Ask patients to point to the exact location of the pain, either on themselves, on you, or on a full-body drawing. Quality—What does your pain feel like? Is it sharp or dull? Does it ache? Is it shooting or stabbing? Burning or tingling? These questions can help distinguish neuropathic pain from nociceptive pain. Intensity—On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 the most intense pain you can imagine, how would you rank your pain now? How would you rank your pain at its worst? And at its best? A pain intensity scale (see below) can be very helpful for this assessment. Modulating factors—What makes your pain worse? What makes it better? Previous treatment—What treatments have you tried to relieve your pain (eg, analgesics, acupuncture, relaxation techniques)? Are they effective now? If not, were they ever effective in the past? Impact—How does the pain affect your ability to function, both physically and socially? For example, does the pain interfere with your general mobility, work, eating, sleeping, socializing, or sex life? • The impact of significant pain on the patient in the past • The patient’s usual coping responses to pain and stress • The patient’s preferences regarding pain management methods • The patient’s concerns about using opioids and other controlled substances (anxiolytics, stimulants) • Changes in the patient’s mood (anxiety, depression) brought on by cancer and pain • The impact of cancer and its treatment on the family • The level of care the family can provide and the potential need for outside help (eg, hospice) Pain intensity scales are useful tools for assessing pain intensity. Representative scales are shown in Figures 29–2 and 29–3. The descriptive scale and numeric scale (Fig. 29–2) are used for adults and older children. The pain affect FACES scale (Fig. 29–3) is used for young children and for patients with cognitive impairment, who may have difficulty understanding the descriptive and numeric scales. • Nonopioid analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and acetaminophen) • Opioid analgesics (eg, oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine) • Adjuvant analgesics (eg, amitriptyline, carbamazepine, dextroamphetamine) Selection among the analgesics is based on pain intensity and pain type. To help guide drug selection, the World Health Organization (WHO) devised a drug selection ladder (Fig. 29–4). The first step of the ladder—for mild to moderate pain—consists of nonopioid analgesics: NSAIDs and acetaminophen. The second step—for more severe pain—adds opioid analgesics of moderate strength (eg, oxycodone, hydrocodone). The top step—for severe pain—substitutes powerful opioids (eg, morphine, fentanyl) for the weaker ones. Adjuvant analgesics, which are especially effective against neuropathic pain, can be used on any step of the ladder. Specific drugs to avoid are listed in Table 29–2. TABLE 29–2 Drugs That Are Not Recommended for Treating Cancer Pain *Brompton’s cocktail consists of heroin (in variable amounts), 10 mg of cocaine, 2.5 mL of 98% ethanol, 5 mL of syrup, and chloroform water. Drug therapy of cancer pain should adhere to the following principles: • Perform a comprehensive pretreatment assessment to identify pain intensity and the underlying cause. • Individualize the treatment plan. • Use the WHO analgesic ladder and NCCN guidelines to guide drug selection. • Use oral therapy whenever possible. • Avoid IM injections whenever possible. • For persistent pain, administer analgesics on a fixed schedule around-the-clock (ATC), and provide additional rescue doses of a short-acting agent if breakthrough pain occurs. • Evaluate the patient frequently for pain relief and drug side effects. The nonopioid analgesics—NSAIDs and acetaminophen—constitute the first rung of the WHO analgesic ladder. These agents are the initial drugs of choice for patients with mild pain. There is a ceiling to how much pain relief nonopioid drugs can provide. Hence, there is no benefit to exceeding recommended dosages (Table 29–3). Acetaminophen is about equal to the NSAIDs in analgesic efficacy but lacks anti-inflammatory actions. Because of this difference and others, acetaminophen is considered separately below. The NSAIDs and acetaminophen are discussed at length in Chapter 71. Accordingly, discussion here is brief. TABLE 29–3 Dosages for Nonopioid Analgesics: Acetaminophen and Selected NSAIDs *All dosages are oral except where indicated. †Magnesium salicylate and sodium salicylate are nonacetylated, and hence, unlike aspirin, are safe for patients with thrombocytopenia. The opioids are discussed at length in Chapter 28. Discussion here focuses on their use in patients with cancer.

Pain management in patients with cancer

Management strategy

Flow chart for pain management in patients with cancer.

Flow chart for pain management in patients with cancer.

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. (Adapted from Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, et al: Management of Cancer Pain [Clinical Practice Guideline No. 9; AHCPR Publication No. 94-0592]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1994.)

Assessment and ongoing evaluation

Comprehensive initial assessment

Assessment of pain intensity and character: the patient self-report

Psychosocial assessment

Pain intensity scales

Linear pain intensity scales.

Linear pain intensity scales.

*If used as a graphic rating scale, a 10-cm baseline is recommended. (From Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma [Clinical Practice Guideline No. 1; AHCPR Publication No. 92-0032]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992.)

Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale.

Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale.

Explain to the patient that the first face represents a person who feels happy because he or she has no pain, and that the other faces represent people who feel sad because they have pain, ranging from a little to a lot. Explain that face 10 represents a person who hurts as much as you can imagine, but that you don’t have to be crying to feel this bad. Ask the patient to choose the face that best reflects how he or she is feeling. The numbers below the faces correspond to the values in the numeric pain scale shown in Figure 29–2. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2009.)

Drug therapy

Drug Class

Drug

Why the Drug Is Not Recommended

Opioids

Pure agonists

Meperidine

A toxic metabolite accumulates with prolonged use

Codeine

Maximal pain relief is limited owing to dose-limiting side effects

Agonist-antagonists

Buprenorphine

Butorphanol

Nalbuphine

Pentazocine

Ceiling to analgesic effects; can precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; cause psychotomimetic reactions

Opioid Antagonists

Naloxone

Naltrexone

Nalmefene

Can precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; limit use to reversing life-threatening respiratory depression caused by opioid overdose

Benzodiazepines

Diazepam

Lorazepam

others

Sedation from benzodiazepines limits opioid dosage; no demonstrated analgesic action

Barbiturates

Amobarbital

Secobarbital

others

Sedation from barbiturates limits opioid dosage; no demonstrated analgesic action

Miscellaneous

Cocaine

No analgesic efficacy, either alone or in combination with an opioid

Marijuana

Side effects (dysphoria, drowsiness, hypotension, bradycardia) preclude routine use as an analgesic

Brompton’s cocktail*

Analgesic efficacy is no better than that of a single opioid

The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management.

The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management.

Note that steps represent pain intensity. Accordingly, if a patient has intense pain at the outset, then treatment can be initiated with an opioid (step 2), rather than trying a nonopioid first (step 1). (Adapted from Cancer Pain Relief, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996.)

Nonopioid analgesics

Usual Adult Dosage*

Drug

Body Weight 50 kg or More

Body Weight Less Than 50 kg

Acetaminophen

650 mg q 4 h or 975 mg q 6 h or 1300 mg q 8 h

10–15 mg/kg q 4 h or 15–20 mg/kg q 4 h (rectal)

NSAIDs: Salicylates

Aspirin

650 mg q 4 h or 975 mg q 6 h

10–15 mg/kg q 4 h or 15–20 mg/kg q 4 h (rectal)

Magnesium salicylate [Magan]†

650 mg q 4 h

—

Sodium salicylate

325–650 mg q 3–4 h

—

NSAIDs: Propionic Acid Derivatives

Fenoprofen

300–600 mg q 6 h

—

Ibuprofen [Motrin, Advil, others]

400–800 mg q 6 h

10 mg/kg q 6–8 h

Ketoprofen

25–60 mg q 6–8 h

—

Naproxen [Naprosyn]

250–275 mg q 6–8 h

5 mg/kg q 8 h

Naproxen sodium [Anaprox, Aleve, Naprelan, others]

275 mg q 6–8 h

—

NSAIDs: Miscellaneous

Diflunisal

500 mg q 12 h

—

Etodolac

200–400 mg q 6–8 h

—

Meclofenamate sodium

50–100 mg q 6 h

—

Mefenamic acid [Ponstel, Ponstan ![]() ]

]

250 mg q 6 h

—

NSAIDs: Selective COX-2 Inhibitors

Celecoxib [Celebrex]

200 mg q 12 h

—

Opioid analgesics

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pain management in patients with cancer

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access