Pain Management for Childbirth

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Compare childbirth pain with other types of pain.

• Describe how excessive pain can affect the laboring woman and her fetus.

• Examine how physical and psychologic forces interact in the laboring woman’s pain experience.

• Describe use of nonpharmacologic pain management techniques in labor.

• Describe how medications may affect a pregnant woman and the fetus or neonate.

• Identify the benefits and risks of specific pharmacologic pain-control methods.

• Explain nursing care related to different types of intrapartum pain management.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

Each woman has unique expectations about birth, including expectations about pain and her ability to manage it. The woman who successfully handles the pain of labor is more likely to view her experience as a positive life event. A woman’s experience with labor pain varies with several physical and psychologic elements, and each woman responds differently. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods give the nurse and laboring woman a selection of pain management techniques to choose from.

Unique Nature of Pain During Birth

Pain is subjective and personal; no one can feel another’s pain. One must simply believe what another person says about his or her pain experience.

Childbirth pain, however, differs from other pain in several important respects:

Adverse Effects of Excessive Pain

Although expected during labor, pain that exceeds a woman’s tolerance can have harmful effects on her and the fetus.

Physiologic Effects

Labor increases a woman’s metabolic rate and her demand for oxygen. Pain and anxiety escalate her already high metabolic rate by increasing production of catecholamines, or “fight or flight” hormones (epinephrine and norepinephrine), cortisol, and glucagon. She may breathe fast to obtain more oxygen, exhaling too much carbon dioxide in the process, and having less oxygen to share with her fetus. Significant changes, more than those expected during labor, can occur in the woman’s arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) and partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) and in her arterial pH. These maternal respiratory and metabolic changes alter placental exchange of oxygen and waste products, even in the presence of normal placental circulation. The fetus has less oxygen available for uptake and is less able to unload carbon dioxide to the mother. The net result is that the fetus shifts to anaerobic metabolism, with the buildup of hydrogen ions (metabolic acidosis).

Excessive catecholamine secretion inhibits uterine response to oxytocin secretion of the posterior pituitary. Contractions become shorter, less frequent, and less effective, slowing labor progress.

High catecholamine levels reduce blood flow to the uterus and placenta. The fetus is more likely to become hypoxic and eventually shift to anaerobic metabolism if good placental blood flow is not restored. In addition, contractions become irritable, cramplike, and poorly effective, possibly resulting in dystocia and inhibiting labor progress, thus increasing pain further (see Chapter 27).

Psychological Effects

Poorly relieved pain lessens the pleasure of this extraordinary life event for both partners. The mother may find it difficult to interact with her infant because she is depleted from a painful, exhausting labor. Unpleasant memories of the birth may affect her response to sexual activity or another labor. Her partner may feel inadequate as a support person during birth.

Variables in Childbirth Pain

Physical and psychosocial factors contribute to a woman’s response to the pain of labor.

Physical Factors

Childbirth pain is of two types—visceral and somatic. Visceral pain is a slow, deep pain that is poorly localized. It is often described as dull or aching. Visceral pain dominates during first-stage labor as the uterus contracts and the cervix dilates.

Somatic pain is a faster, sharp pain. It can be precisely localized. Somatic pain is most prominent during late first-stage labor and during second-stage labor as the descending fetus puts direct pressure on maternal tissues.

Sources of Pain

Four potential sources of labor pain exist in most labors. Other physical factors may modify labor pain, increasing or decreasing it.

Tissue Ischemia

The blood supply to the uterus decreases during contractions, leading to tissue hypoxia and anaerobic metabolism. Ischemic uterine pain has been likened to ischemic heart pain.

Cervical Dilation

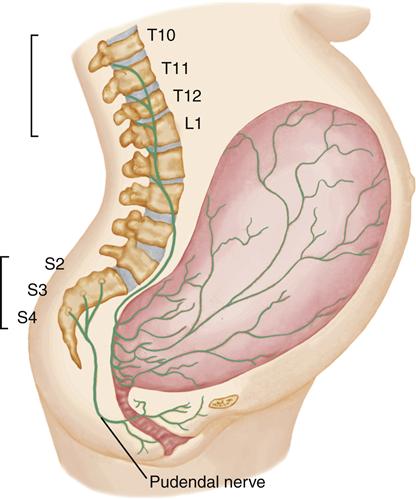

Dilation and stretching of the cervix and lower uterus are a major source of pain. Pain stimuli from cervical dilation travel through the hypogastric plexus, entering the spinal cord at the T10, T11, T12, and L1 levels (Figure 18-1).

Pressure and Pulling on Pelvic Structures

Some pain results from pressure and pulling on pelvic structures such as ligaments, fallopian tubes, ovaries, bladder, and peritoneum. The pain is a visceral pain; a woman may feel it as referred pain in her back and legs.

Distention of the Vagina and Perineum

Marked distention of the vagina and perineum occurs with fetal descent, especially during the second stage. The woman may describe a sensation of burning, tearing, or splitting (somatic pain). Pain from vaginal and perineal distention and pressure and pulling on adjacent structures enters the spinal cord at the S2, S3, and S4 levels (see Figure 18-1).

Factors Influencing the Perception or Tolerance of Pain

Although physiologic processes cause labor pain, a woman’s tolerance of pain may be affected by other physical influences.

Intensity of Labor

The woman who has a short, intense labor often complains of severe pain because each contraction does so much work (effacement, dilation, and fetal descent). A rapid labor may limit her options for pharmacologic pain relief as well.

Cervical Readiness

If prelabor cervical changes (softening, with some dilation and effacement) are incomplete, the cervix does not open as easily. More contractions are needed to achieve dilation and effacement, resulting in a longer labor and greater fatigue in the laboring woman.

Fetal Position

Labor is likely to be longer and more uncomfortable when the fetus is in an unfavorable position. An occiput posterior fetal position is a common variant seen in otherwise normal labors. In this position, each contraction pushes the fetal occiput against the woman’s sacrum. She experiences intense back discomfort (back labor) that persists between contractions. Often a woman cannot deliver her infant in the occiput posterior position. The fetal head must therefore rotate in a wider arc before the mechanisms of extension and expulsion occur, so labor is often longer (see Chapter 16). Back pain may decrease dramatically when a fetus rotates into the more favorable occiput anterior position. The rate of labor progress usually increases as well.

Characteristics of the Pelvis

The size and shape of a woman’s pelvis influence the course and length of her labor. Abnormalities may cause a difficult and longer labor and may contribute to fetal malpresentation or malposition.

Fatigue

Fatigue reduces a woman’s ability to tolerate pain and to use coping skills she has learned. She may be unable to focus on relaxation and breathing techniques that would otherwise help her tolerate labor.

Many women sleep poorly during the last weeks of pregnancy. Shortness of breath when lying down, frequent urination, and fetal activity interrupt sleep so that a woman often begins labor with a sleep deficit. If labor begins late in the evening, she may have been awake well over 24 hours by the time she gives birth. Even if a woman begins labor well rested, slow progress may exhaust her. Women who have scheduled labor induction may have as much fatigue as those who have spontaneous labor.

Prolonged, intense pushing during the second stage is exhausting as well. For this reason, promoting a physiologic second stage in which the woman delays pushing until she feels an urge to do so (“laboring down”) is preferred (see Chapter 16).

Intervention of Caregivers

Although they may be needed for the well-being of a woman and fetus, some interventions add discomfort to the natural pain of labor. Intravenous (IV) lines cause pain when they are inserted and remain noticeable to many women during labor. Fetal monitoring equipment and the frequent need to adjust the sensors is uncomfortable to some women. Both may hamper a woman’s mobility, which she might use to assume a more comfortable position. A woman often prefers to hear her baby despite any discomforts however.

A woman whose labor is induced or augmented often reports more pain and increased difficulty coping with it because contractions reach peak intensity quickly rather than gradually over many hours. Vaginal examinations and amniotomy are uncomfortable because of vaginal and cervical stretching.

Psychosocial Factors

Several psychosocial variables influence a woman’s experience of pain.

Culture

A woman’s sociocultural roots influence how she perceives, interprets, and responds to pain during childbirth. Some cultures encourage loud and vigorous expression of pain, whereas others value self-control. Women are individuals within their cultural groups, however. The experience of pain is personal, and one should not make assumptions about how a woman from a specific cultural or ethnic group will behave during labor.

Women should be encouraged to express themselves in any way they find comforting, and the diversity of their expressions must be respected. Accepting a woman’s individual response to labor and pain promotes a therapeutic relationship.

The nurse should avoid praising some behaviors (e.g., stoicism) while belittling others (e.g., noisy expression). This restraint is difficult because noisy women are challenging to work with and may disturb others.

The unique nature of childbirth pain and women’s diverse responses to it make nursing management complex. The nurse can miss important cues if the woman is either stoic, having little outward expression of pain, or expresses herself loudly and constantly. With either extreme, the nurse may not readily identify critical information such as impending birth or the symptoms of a complication.

Anxiety and Fear

Extreme anxiety and fear magnify sensitivity to pain and impair a woman’s ability to tolerate it. They consume energy she needs to cope with the birth process, including its painful aspects.

Anxiety and fear increase muscle tension, diverting oxygenated blood to the brain and skeletal muscles. Tension in pelvic muscles counters the expulsive forces of uterine contractions and the laboring woman’s pushing efforts during the second stage. Prolonged tension results in general fatigue, increased pain perception, and reduced ability to use skills to cope with pain.

Previous Experiences with Pain

Early in life, a child learns that pain is a symptom of bodily injury. Consequently, fear and withdrawal are a woman’s natural reactions to pain during labor. Learning about the normal sensations of labor, including pain, helps a woman suppress her natural reactions of fear and withdrawal, allowing her body to do the work of birth.

A woman who has given birth previously has a different perspective. If she has had a vaginal delivery, she is probably aware of normal labor sensations and is less likely to associate them with injury or abnormality. Also, time has a way of blunting the memory of painful experiences.

A woman who had a child by cesarean birth may not have experienced labor and may be particularly anxious about pain. The experience of cesarean birth is known to her, whereas labor is often unknown. Subsequent babies are typically born by cesarean, but spontaneous labor may occur before the scheduled date of her surgery.

A woman who has previously had a long and difficult labor is more likely to be anxious about the outcome of the present one if a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) is planned. If she had a cesarean birth following the difficult labor, she may doubt her ability to give birth vaginally. Her anxiety often intensifies when she reaches the point at which her prior labor ended with the cesarean birth.

Previous experiences do not always adversely affect a woman’s ability to deal with pain. She may have learned ways to cope with pain during other episodes of pain or during other births and may use these skills adaptively during labor.

Preparation for Childbirth

Preparation for childbirth does not ensure a pain-free labor. A woman should be prepared for pain realistically, including reasonable expectations about analgesia and anesthesia (loss of sensation with or without loss of consciousness). She may feel that her entire preparation is invalid if what she expects does not happen when she is in labor.

Preparation reduces anxiety and fear of the unknown. It allows a woman to rehearse for labor and learn a variety of skills to master pain as labor progresses. She and her partner learn about expected behavioral changes during labor, and their knowledge decreases their anxiety when those changes occur.

Support System

An anxious partner or other support person is less able to provide the encouragement and reassurance that the woman needs during labor. In addition, anxiety in others can be contagious, and an anxious partner can increase the woman’s anxiety. She may assume that if others are worried, something is probably wrong.

The birth experiences of a woman’s family and friends cannot be ignored. Those individuals can be an important source of comfort and assistance if they convey realistic information about labor pain and its control. If they describe labor as simply intolerable with no relief steps taken, however, the woman may have needless distress. It is equally detrimental for a woman to hear that labor is painless. No two labors are alike, even for the same woman.

Standards for Pain Management

The Joint Commission (www.jointcommission.org), previously known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, has recognized that pain management is an essential part of care in all health care settings. Joint Commission standards require health care organizations to (The Joint Commission, 2011):

Nonpharmacologic Pain Management

The nurse who cares for women in labor and birth can offer nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic pain management methods. Education about nonpharmacologic pain management is the foundation of prepared childbirth classes. To be most helpful to women and their labor partners, the intrapartum nurse should know methods that are taught in local childbirth classes.

Advantages

Nonpharmacologic methods have several advantages over pharmacologic methods if they produce adequate pain control. They do not slow labor and have no side effects, nor do they carry the risk of allergy or sedation.

Nonpharmacologic techniques are both an alternative to and an adjunct to drugs. Most women use a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic techniques. The woman who chooses pharmacologic analgesia needs alternative pain management until the drug is given, usually after labor is established. Also, pharmacologic methods may not eliminate labor pain, and a woman may need nonpharmacologic methods to control the pain that remains. Nonpharmacologic techniques may help a person manage pain other than birth-related pain.

Nonpharmacologic methods may be the only realistic option for a woman who enters the hospital in advanced, rapid labor. In this case, there may not be time to obtain a good regional block or achieve analgesia from systemic drugs. Also, the newborn might have respiratory depression if a systemic opioid narcotic reaches its peak action near the time of birth.

Limitations

Nonpharmacologic methods of pain control have limitations, especially if they are used as the sole method of pain control. Women do not always achieve their desired level of pain control using these methods alone. Because of the many variables in labor, even a well-prepared and highly motivated woman may have a difficult labor and need pharmacologic analgesia or anesthesia.

Preparation for Pain Management

The ideal time to learn nonpharmacologic pain control is before labor. During the last few weeks of pregnancy, the woman learns about labor, including its painful aspects, in childbirth classes. She can prepare to confront the pain, learning a variety of skills to use during labor. Her support person learns specific methods to encourage and support her. After admission, the nurse can review and reinforce what the partners learned in class.

The nurse can teach the unprepared woman and her support person nonpharmacologic techniques. The latent phase of labor is the best time for intrapartum teaching because the woman is usually anxious enough to be attentive and interested, yet comfortable enough to understand.

Many methods may become less effective after prolonged use, a process called habituation. Changing techniques counters habituation. The nurse who knows a variety of methods can select those that are most helpful to an individual woman.

Application of Nonpharmacologic Techniques

Four categories can be applied to intrapartum care: relaxation, cutaneous stimulation, mental stimulation, and breathing.

Relaxation

Promoting relaxation provides a base for all other methods, both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic, because it does the following:

• Promotes uterine blood flow, thus improving fetal oxygenation

• Promotes efficient uterine contractions

Environmental Comfort

Comfortable surroundings support relaxation. The nurse can reduce irritants, such as bright lights, and can adjust the room temperature.

Music masks outside noise and provides a background for use of imagery and breathing techniques. It is a distraction that shifts the woman’s attention from bodily sensations. Television may have the same effect for some women.

General Comfort

Promoting the woman’s personal comfort helps her focus on pain management during labor (Figure 18-2). This includes actions to increase comfort and reduce the effect of irritants, such as a hot environment or wet bedding.

Assuming a comfortable position, changing positions as desired, and walking often improve a woman’s ability to tolerate the discomforts of labor (see Chapter 16). However, only about 25% of women reported walking around after active labor had started in a national survey of women (Declerq, Sakala, Corry, et al., 2006).

Reducing Anxiety and Fear

The nurse may reduce a woman’s anxiety and increase her self-control by providing accurate information and focusing on the normality of birth. Hospitals are typically associated with illness or injury, situations that are anxiety provoking. Yet hospitals are the most common site for the normal event of birth in the United States.

Simple nursing actions keep the focus on the normality of childbirth, regardless of the setting. For example, referring to a woman as a patient reinforces the atmosphere of illness associated with being in a hospital, whereas calling her by name helps her to see birth as a normal process. Empowerment of the woman and her partner by giving them choices whenever possible helps them see themselves as competent people who can accomplish the task of giving birth.

Implementing Specific Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation techniques work best if they are learned and practiced before labor. During practice sessions at home, couples may practice progressive relaxation, in which the woman contracts and then releases specific muscle groups until all muscles are relaxed. Neuromuscular dissociation helps the woman learn to relax all muscles except those that are working (the uterus or the abdominal muscles when pushing). The woman can learn touch relaxation in response to her partner’s touch, and relaxation against pain as the partner deliberately causes mild pain and the woman learns to relax despite the pain.

Even if the woman did not practice these relaxation techniques at home, the nurse can teach her how to consciously relax as labor goes by. The partner can learn to watch for signs of tension, touch that area, and direct the woman to relax.

Cutaneous Stimulation

Cutaneous stimulation has several variations that are often combined with each other or with other techniques.

Self-Massage

The woman may rub her abdomen, legs, or back in a self-massage called effleurage to counteract discomfort. Some women find abdominal touch irritating, especially near the umbilicus. Women in labor may find firm stroking more helpful than very light stroking. They can trace figure eights or circles on the bed if touch irritates them.

Some women benefit from firm palm or sole stimulation during labor. They may like to have their palms rubbed vigorously by another, rub their hands or feet together, or bang their palms on, or grip, a cool surface. They may hold another person’s hand tightly during a contraction. The nurse should determine if these actions indicate excess pain or if they are a woman’s way of countering pain and therefore useful.

Massage by Others

The partner or the nurse can rub the woman’s back, shoulders, legs, or any area where she finds massage helpful. Sacral pressure is a variation that may help when the woman has back pain, which is usually most intense when the fetus is in an occiput posterior position. Sacral pressure may be applied using the palm of the hand, the fist or fists, or a firm object such as two tennis balls in a sock (Figure 18-3).

Nonclinical touch by the nurse is a powerful tool if the woman does not object to it. Holding her hand, stroking her hair, or similar actions convey caring, comfort, affirmation, and reassurance at this vulnerable time.

Thermal Stimulation

Many women like to have warmth applied to their back, abdomen, or perineum during labor. A warm shower, tub bath, or whirlpool bath is relaxing and provides thermal stimulation. A sock filled with dry rice and microwaved provides gentle warmth and can be used to apply pressure to the sacral area.

Cool, damp washcloths may be comforting, especially if a woman is hot. She may put them on her head, throat, abdomen, or any place she wants. She also may want to put them in or over her mouth to relieve dryness.

Acupressure

Acupressure is a directed form of massage in which the support person applies pressure to specific pressure points using hands, rollers, balls, or other equipment. It is related to its invasive counterpart, acupuncture, in which tiny needles are inserted into similar points. Acupuncture and acupressure have data to support effectiveness to relieve nausea and vomiting, including “morning sickness” of pregnancy. Few controlled studies exist on its usefulness during birth. For updated objective information on acupressure and other complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) techniques, visit the website for the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, one of the institutes of the National Institutes of Health (www.nncam.nih.gov).

Hydrotherapy

Water therapy (Box 18-1) in the form of a shower, tub bath, or whirlpool can supplement any relaxation technique. The buoyancy afforded by immersion supports the body, equalizes pressure, and aids muscle relaxation. In addition, fluid shifts from the extravascular space to the intravascular space, reducing edema as the excess fluid is excreted by the kidneys. Providing hydrotherapy requires a supportive environment, adequate nursing policies and staffing, and collaborative relationships among nurses and other providers of care. Additional research needs to be done relative to concerns about ascending maternal vaginal infections and adequate cleaning of tubs to prevent maternal or newborn infections (Creehan, 2008; Declerq et al., 2006; Stark, Rudell, & Haus, 2008; Stark & Miller, 2009).

Mental Stimulation

Mental techniques occupy the woman’s mind and compete with pain stimuli. They also aid relaxation by providing a tranquil imaginary atmosphere.

Imagery

If the woman has not practiced a specific imagery technique, the nurse can help her create a relaxing mental scene. Most women find images of warmth, softness, security, and total relaxation most comforting.

Imagery can help the woman dissociate herself from the painful aspects of labor. For example, the nurse can help her visualize the work of labor: the cervix opening with each contraction or the fetus moving down toward the outlet each time she pushes. This technique is like visualizing success or movement toward a goal with each contraction.

Focal Point

When using nonpharmacologic techniques, a woman may prefer to close her eyes or may want to concentrate on an external focal point. Keeping her eyes on a focal point may help the woman concentrate on something outside her body and thus away from the pain from contractions. She may bring a picture of a relaxing scene or an object to use as a focal point and to aid in the use of imagery. She can use any point in the room as a focal point.

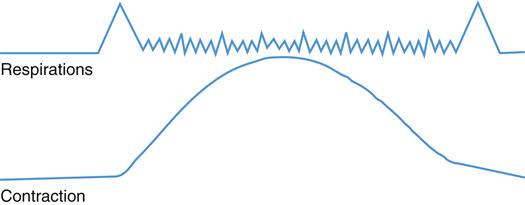

Breathing Techniques

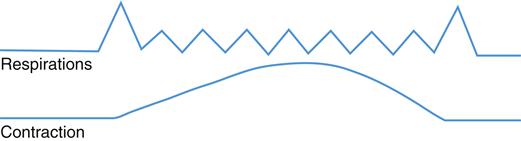

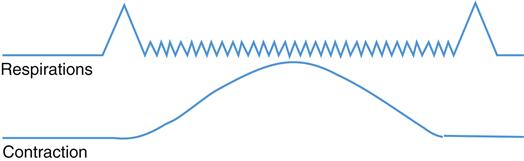

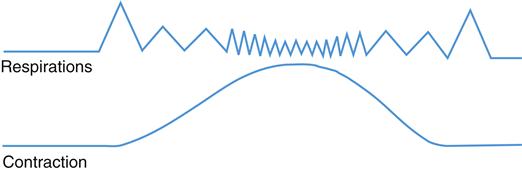

Breathing techniques provide a different focus during contractions, interfering with pain sensory transmission (Figure 18-4). Breathing techniques often supplement other nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic techniques. Techniques begin with simple breathing patterns and progress to more complex ones as needed. There is no single right time to begin using breathing techniques or to change patterns during labor. Prolonged use of complex breathing techniques can be tiring, however.

First-Stage Breathing

Breathing in the first stage of labor consists of a cleansing breath and various breathing techniques known as paced breathing. The method begins with a very simple technique that is used as long as possible. When it is no longer effective, breathing that requires more concentration is added.

Cleansing Breath

Each contraction in first and second stages begins and ends with a deep inspiration and expiration known as the cleansing breath. Like a sigh, a cleansing breath helps the woman release tension. It provides oxygen to help prevent myometrial hypoxia, one cause of pain in labor. The cleansing breath also helps the woman clear her mind to focus on relaxing and signals her labor partner that the contraction is beginning or ending. The woman may inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth or take her cleansing breath in any way comfortable for her.

Slow-Paced Breathing

The first breathing is slow-paced breathing, a slow, deep breathing that increases relaxation (Figure 18-5). The woman should concentrate on relaxing her body rather than on regulating the rate of her breathing. Relaxation naturally brings about slower breathing, similar to that which occurs during sleep. She can use nose, mouth, or combination breathing, depending on which is most comfortable.

The woman uses slow-paced breathing as long as possible during labor because it promotes relaxation and sufficient oxygenation. Slow-paced breathing is easy for the unprepared woman to learn between contractions and, with the support of the nurse, helps even a frightened woman become calm and able to work with her contractions.

Modified-Paced Breathing

When the woman finds that slow-paced breathing is no longer effective, she begins modified-paced breathing (Figure 18-6). This chest breathing at a faster rate matches the natural tendency to use more rapid breathing during stress or physical work, such as labor. Although modified-paced breathing is more shallow than slow-paced breathing, the faster rate allows oxygen intake to remain about the same. As with slow-paced breathing, the focus is on release of tension rather than on the actual number of breaths taken.

Women can combine slow- and modified-paced breathing during the course of a contraction (Figure 18-7). They begin slowly and use shallow, faster breathing at the peak of the contraction. Breathing should not interfere with relaxation but enhance it.

Pattern-Paced Breathing

Pattern-paced breathing (sometimes called “pant blow,” “hee hoo,” or “hee blow” breathing) involves focusing on a rhythmic pattern of breathing (Figure 18-8). It is similar to modified-paced breathing. It differs in that after a certain number of breaths, the woman exhales with a slight emphasis or blow and then begins the modified-paced breathing again. The addition of a blow causes her to focus more on her breathing and reduces habituation. Some educators teach women to make a sound such as “hee” during this breathing and to blow through pursed lips with a “hoo” sound. Others avoid special sounds, which tighten the vocal cords and may decrease relaxation.

The number of breaths before the blow may remain constant (usually between two and six) or may change in a pattern. Variations include a set pattern such as 3-1 or a stairstep pattern such as 6-1, 5-1, 4-1, 3-1. Some couples use a random pattern determined by the coach, who uses hand or verbal signals to show the number of breaths the woman should take before each blow.

Controlling the Urge to Push

If a woman pushes strenuously before the cervix is completely dilated, she risks injury to the cervix and reduced oxygenation of the fetus. Blowing prevents closure of the glottis and breath holding, which are a part of strenuous pushing. The woman blows repeatedly using short puffs when the urge to push is strong. The support person may learn to blow along with her to help the woman concentrate. Some women vary the blowing by using one short breath and one blow.

Common Problems

Hyperventilation and mouth dryness may occur during breathing techniques. Hyperventilation is the result of rapid deep breathing that causes excessive loss of carbon dioxide, eventually resulting in respiratory alkalosis. The woman may feel dizzy or lightheaded and have impaired thinking. Vasoconstriction leads to tingling and numbness in fingers and lips. If hyperventilation continues, tetany caused by decreased calcium in tissues and blood may result in stiffness of the face and lips and carpopedal spasm.

The woman can blow into a paper bag or her own cupped hands if she feels dizzy. Rebreathing exhaled air in this way increases her blood carbon dioxide levels. Reassure the woman that these measures help restore her carbon dioxide level to normal and are relaxing.

Dryness of the mouth occurs when the woman uses prolonged mouth breathing. To avoid dryness, she can place her tongue gently against the roof of her mouth to moisturize entering air. The support person can offer ice, mouthwash, or liquids or encourage her to brush her teeth.

Second-Stage Breathing

Care in the second stage of labor encourages a physiologic completion of labor, assisting the mother to respond to her urge to push rather than directing her to push as soon as her cervix is completely dilated even if she does not feel the urge. Lengthy pushing in second stage has been shown to result in greater maternal fatigue, more operative births, and nonreassuring fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns and does not significantly shorten second stage (Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses [AWHONN], 2008).

With newer techniques of epidural block, women who choose this method of labor pain control often feel the urge to push, although not as strongly as unmedicated women. Using their natural urge to push, even if reduced, helps them push with contractions most effectively. Delaying pushing for up to 1 to 2 hours after complete dilation has shown benefits similar to those of women who do not have epidural analgesia.

Research has shown that strenuous directed pushing increases risk for structural and neurogenic injury to a woman’s pelvic floor. Closed-glottis pushing causes recurrent increases in intrathoracic pressure with a resulting fall in cardiac output and blood pressure. The woman’s lower blood pressure then causes less blood to be delivered to the placenta, resulting in fetal hypoxia that is reflected in nonreassuring fetal heart patterns.

Promoting a physiologic second stage uses nondirected pushing. The woman makes her decision with the nurse about when it is time to start pushing. She may grunt, groan, sigh, or moan as she pushes, and the nurse should validate that these sounds are normal. Pushing three to four times for 6 to 8 seconds is likely to be effective in aiding descent and safe for the baby. Adjust the pushing process depending on fetal status (AWHONN, 2008). See Chapter 16 for more discussion of second stage nursing care.

Pharmacologic Pain Management

Pharmacologic methods for pain management include systemic drugs, regional pain management techniques, and general anesthesia.

Special Considerations When Medicating a Pregnant Woman

Medicating a woman when she is pregnant is not straightforward for several reasons:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree