CHAPTER 19 Pain management

Introduction

Acute pain has been described as a worldwide phenomenon, and the belief that pain is an inevitable part of the human condition is widespread (Brennan et al 2007). The pain and suffering endured by people commands universal interest, and as knowledge and research develops exponentially, science and technology continues to support our understanding of pain treatment and management. Throughout the world it is estimated that tens of millions of people are affected by life-threatening diseases, such as cancer, HIV/AIDS disease, etc., coupled with episodes of acute and chronic enduring pain (Sepúlveda et al 2002). Furthermore, it is estimated that 10 million new cases of cancer are diagnosed annually, and by 2020 this figure will double, with approximately 70% of incidences occurring in the developing nations (Selva 1997), with huge implications for the delivery of safe and ethical pain management.

Pain is an important component, and at times the only element, of disease processes. Pain management and subsequent nursing interventions entail a moral, humanitarian, ethical and legal obligation to ensure that people in our care have their pain relieved. This requires competent and knowledgeable practitioners who are ‘fit for purpose’. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) has identified Essential Skills Clusters (NMC 2007); several subsections within the clusters relate to pain including: Care, Compassion, and Organisational Aspects of Care and Medicines Management (Ellson 2008).

…pain is a critical ethical issue because it has the capacity to dehumanize the human person (Lisson 1987)

Effective pain management as a fundamental human right is a moral imperative that is universally acknowledged, but pain on a global scale remains inadequately treated because of cultural, attitudinal, educational, legal and system-related ideologies (Brennan et al 2007, Fisherman 2007). Today the best available evidence indicates a gap between an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the pathophysiology of pain, and the widespread inadequacy in its treatment. In the poorest and most socially deprived nations, this is exacerbated by the huge numbers affected by HIV/AIDS disease coupled with poverty, war, oppression and violence (Brennan et al 2007). However, pain-related activities in medicine, law and ethics have reached a critical point – it is accepted that pain is ubiquitous and complex, yet often under-treated and at best manageable. The global pain community has now declared that pain management is a human right and that unreasonable failure to treat an individual’s pain is unethical and a breach of human rights (Brennan et al 2007). Furthermore, adequate pain management is founded upon the duty of health practitioners to act ethically. Values and ethics embraced within The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Nurses and Midwives (NMC 2008) reflect the duty of care that nurses have towards those in their care.

Every person, irrespective of age, deserves to be pain free. The particular rights of children are recognised in the National Service Framework for Children, Young People, and Maternity Services (NSF) (Department of Health [DH] 2004), and enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child (United Nations 1989).

Worldwide, there are some outstanding examples of public health programmes for pain management and palliative care. The best have combined policy with an integrated approach and commitment to education. Brennan et al (2007) conclude that pain management is an issue of central importance related to disciplines such as medicine, law and ethics, where they are at an ‘inflection point’. Unreasonable failure to treat an individual’s pain is viewed globally as poor medicine, unethical practice and an abrogation of a fundamental human right (Brennan et al 2007, p. 205).

Nurses working within a multidisciplinary team (MDT) need up-to-date evidence-based knowledge and understanding of pain in order to competently prevent and minimise pain. Davies & Taylor (2003) summarise the information needed by health care staff as:

This chapter outlines some of the central issues relating to pain – the difficulty in defining and describing pain due to its elusive, complex and subjective nature and how historical perspectives, including myths and misconceptions, have helped to shape contemporary practice and policy. Tools for the assessment of pain and the subjects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management are described. The chapter provides interactive boxes, cross-references to relevant chapters (e.g. Chs 9, 26, 31, 33) and suggestions for further reading.

Defining pain: competing perspectives

Historically pain has often been attributed, in some cultures, to wrong doing, suffering and punishment. Pain is described as being multidimensional, embracing physical, psychosocial emotional and spiritual components (Chamley & James 2007, p. 653). Furthermore, the multidimensional nature of pain makes it possible to be with an individual who is in pain and be unaware of their pain. It is therefore increasingly recognised that pain is a complex phenomenon and it is difficult to assign a simple single definition. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) describes pain as:

…an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage (IASP 1994)

Whilst this definition describes both the sensory and emotional aspects of pain it has limitations because it fails to account for other peripheral nervous system (PNS) activity and stimuli within the central nervous system (CNS), and the variable way in which the nervous system can respond to injury. Moreover, this definition disregards the sociocultural aspects of an individual’s life, as pain is influenced by body, mind and culture. Over forty years ago McCaffery (1968) proposed a simple definition which has been widely accepted within nursing and has encouraged nurses to focus upon the patient/client’s pain perspective.

This definition embraces the subjective nature of pain and has encouraged nurses and others to value the person’s reporting of their pain. Despite a lack of consensus on the definition of pain, ongoing research has expanded our understanding of the pain experience. Therefore, health care professionals must be aware of and responsive to an individual’s pain, taking account of many variables which influence the individual’s lived-in experience of pain (Box 19.1).

Historical perspectives and contemporary thinking about pain

The history of pain treatment is extensive: ample literature and documentary evidence describes the pervasive influence and intrusive nature of pain on every facet of life since the earliest human experience (Brennan et al 2007, p. 207). The treatment and management of pain has evolved over the centuries from early treatments with herbs to modern day pain management with drugs and non-pharmacological methods. The antecedents of pain theories and treatments can be traced back to early civilisations which had very different views of pain; often the commonly held belief was that pain was the consequence of, or the punishment for sins committed, or the magical influence of spirits of the dead. Nearly every religion has addressed the issue of pain, and religion, philosophy and folklore have saturated pain with meaning (Brennan et al 2007).

Pain theories have developed from the best available scientific literature yet none of them has been able to completely explain the phenomenon of pain and all have shortcomings. Wall (2007) asserts that over the last three decades there has been sustained scientific development and refinement of pain theories and science now rejects the model of a pain mechanism, which has a dedicated action, and ‘fixed rigid modality’. The process which produces pain is described as plastic and changing sequentially over time. The essential mobility of the pain mechanism exists in damaged tissue in the PNS. The movement of pathology from the periphery to the centre triggers reactive processes in the brain. Ultimately this presents the practitioner with a scattered and potentially migrating target (Wall 2007).

Theories of pain

Specificity theory

Descartes (1596–1650) proposed what is described as the classic specificity theory. This traditionally held theory proposed a direct channel for pain from the periphery of the body to the brain, proposing that when the body was exposed to a painful stimulus, this was relayed to the brain by a specific pain pathway. The historical importance of this theory should not be underestimated, and it is only relatively recently that more refined theories have been proposed and accepted, thus demonstrating the inherent inadequacies of specificity theory (Latham 1991). According to Melzack & Wall (1999) its biggest flaw is that it cannot account for how a single stimulus can create different responses including emotional and cognitive.

Pattern or summation theory

According to Field & Smith (2008) the pattern theory was dominant from the end of the nineteenth century until the early 1960s. Goldscheider, at the end of the nineteenth century, proposed the pattern or summation theory which was based upon the excitatory effects of converging stimuli. He claimed that the summation of the skin impulses had a sensory input at the dorsal horn cells and produced particular patterns of nerve impulses that produced pain. When receptors normally activated by non-noxious heat or touch were subject to excessive stimulation or pathological conditions these would enhance the summation of impulses and eventually produce acute pain, and abnormally long periods of summation would produce chronic pain (Latham 1991). In 1943, Livingstone first proposed a central summation theory asserting that a central neural mechanism was responsible for pain syndromes such as phantom limb pain. However, this was strongly counter-argued because when surgical lesions of the spinal cord are performed, in the majority of cases this does not eliminate pain for any sustained length of time, indicating that a mechanism operates at a higher level than the dorsal horns.

Gate control theory

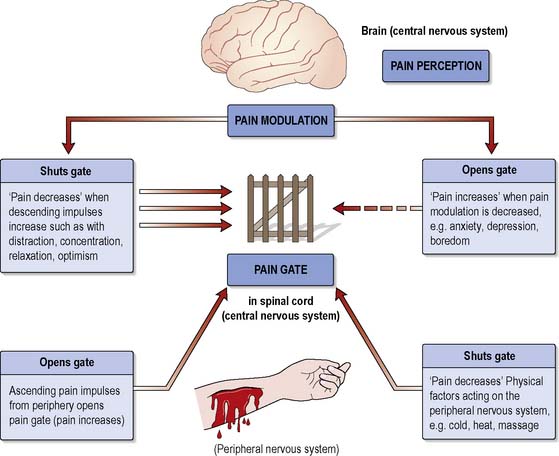

Gate control theory was developed by Melzack & Wall (1965). According to this theory, the transmission of information from a potentially painful stimulus can be modified by a gating mechanism situated in the cells (substantia gelatinosa) of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This mechanism can increase or decrease the flow of nerve impulses from the periphery to the CNS. If the gate is open, impulses pass through; if it is partially open, some pass through; and if shut, no impulses get through and pain is not experienced.

Melzack & Wall (1965), in their seminal text, argued that whether the gate is open or closed is determined by:

Melzack & Wall (1965) proposed that the substantia gelatinosa is activated by large A-β fibres that shut the gate and inhibited by small A-δ and C fibres that open the gate. This activity then influences the information sent to the brain, which in turn initiates descending inhibitory controls depending on the information from other areas such as the cortex (Figure 19.1)

Closing the gate at the brain stem level can sometimes be achieved by ensuring sufficient sensory input, e.g. by using distraction (see p. 570). Similarly, at the level of the cortex/thalamus, the gate can be closed by reducing anxiety, e.g. by providing accurate information about the cause, likely course and relief of pain and thereby increasing the person’s confidence and sense of control.

Factors that may exacerbate pain (i.e. opening the gate) may include injury, anxiety, low mood, fatigue or boredom and focusing too much upon the pain (Chamley & James 2007).

Interestingly, Descartes had earlier made the observation for which Melzack, Wall and others such as Beecher take credit: that the nervous system has the ability to regulate the intensity of the pain experience (Grady et al 2007).

Pain physiology and functional anatomy – an overview

A basic overview of pain physiology and functional anatomy is provided. Readers requiring more information should consult their own anatomy and physiology books, or Further reading (e.g. Clancy & McVicar 2009). The structures and substances involved in the pain sensation include:

Silent nociceptors which are inactive or in a resting state, refractory to mechanical or electrical stimuli. However, in the presence of tissue damage or inflammation the nociceptors ‘switch on’ and become active. It is believed that although these are described as silent from the point of nerve impulse propagation, they do provide the sensory system with continuous data from the tissue environment, which is signalled to the spinal cord via microtubular mechanisms in the axon of nerve cells (Grady et al 2007).

Classification of types of pain

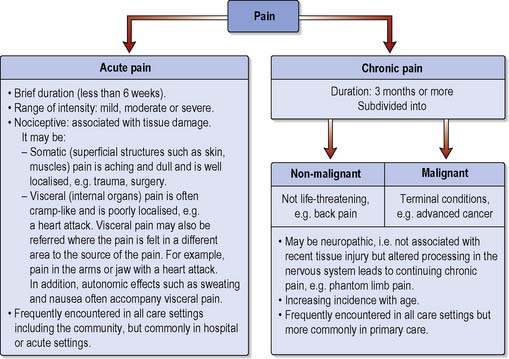

In order for nurses to provide evidence-based care it is crucial to understand the person’s pain experience, which in its broadest sense is classified according to timescale (Chamley & James 2007) (Figure 19.2). However, timescale may be too simplistic for the complex spectrum of the pain experience.

Pain may be classified according to factors such as the presumed origin that may include related pathology and type of pain or clinical speciality and client group. Historically pain was distinguished as being either acute or chronic, but clear distinctions between the two are not easily discernable (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). Horn & Munafo (1997) propose that acute and chronic pain may be usefully regarded as being at the ends of a spectrum rather than being fundamentally separate conditions.

Acute pain

This is often described as being short lived, that is less than 6 weeks, and is commonly nociceptive pain associated with surgery, trauma or acute disease. Acute pain will usually diminish as healing occurs before ceasing completely. Acute pain may occur suddenly or the onset may be slower. It can be of any intensity ranging from a mild headache to agonising chest pain with a major heart attack (see Ch. 2). Ongoing time-limited pain (chronic–acute) may last for a prolonged period but usually it will cease once the cause is removed or treated such as with burns pain. Four processes are involved in acute nociceptive pain: transduction, transmission, modulation and perception (McCaffery & Pasero 1999):

Modulation

Nerves descending from the brain stem to the spinal cord close the gate by releasing endogenous opioids, and this may be the reason why nociceptive pain is responsive to opioids and accounts for the variation in pain perception seen in clinical practice. That is, some patients have more effective modulation than others (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). Chamley & James (2007) draw our attention to the ‘placebo effect’ which has been identified in individuals who have an analgesic response to a masked inert substance (such as a sugar pill) in a double-blind trial of inert substance versus an active drug. Some individuals respond to the placebo whilst others have a poor or no response. Placebo responders may be those with a well-developed endogenous opioid system (Chamley & James 2007).

Perception

is the end result of neural activity where pain becomes a conscious multidimensional experience. As there is no ‘pain centre’ in the brain, pain perception occurs through an ‘action system’. Opioid-binding sites have been identified in several parts of the brain, indicating that they have a role in pain perception. When painful stimuli are transmitted to the brain stem and thalamus, multiple cortical areas are activated and a response is elicited. The first aspect of pain perception is warning and protection and the individual would rapidly assess what has occurred and initiate action (Melzack & Wall 1988), but psychological factors also have an important role, for example anxiety, emotional distress and helplessness are known to increase pain perception. The person’s previous experiences of pain will influence their response.

The perception of pain is complex and dynamic involving sensory impulses relayed from the pain gates and activation of pain responses mediated through the reticular system, somatosensory cortex and the limbic system (Wood 2008).

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

The neurophysiology of acute pain is complex and intense acute pain is often accompanied by physiological effects, e.g. tachycardia, sweating, as the body responds to the potent stressor (see Ch. 17). Initially these are activated by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system and are referred to as ‘flight or fight’ responses which are automatic, primitive survival mechanisms. It is important for nurses to understand the physiological and behavioural effects of pain (Box 19.2). This is crucial when caring for people who have difficulties in communication or are unable to articulate their pain such as pre-verbal children, some individuals who have learning disabilities and associated communication problems or people with dementia.

Referred pain

Stannard & Booth (2004) describe trigger points which are also associated with referred pain. These are small areas of hypersensitivity located in muscles or connective tissue, and when they are triggered the pain is felt at a distance. This type of referred pain is not aligned to a dermatome but stimulation will produce pain in a predictable location.

Chronic pain

When acute pain has not resolved after 3 months it is termed chronic (British Pain Society & Royal College of Anaesthetists 2003). However, increased knowledge of the pathophysiology of disorders that were traditionally associated with chronic pain has made the classification by time potentially redundant (IASP 1994). Increasingly, the term ‘persistent pain’ is used to describe chronic pain, and to classify pain by pathophysiological mechanisms including nociceptive and neuropathic pain (see below). Nociceptive pain is caused by tissue damage, whereas neuropathic pain describes pain that persists beyond the original cause, such as a nerve injury or infective cause. These pain types are defined as non-life threatening (benign) or non-malignant. Pain may be intermittent, for example irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), rheumatoid arthritis or back pain. The pain has not responded to conventional treatment and may last for life. Low back pain currently accounts for over 50% of all musculoskeletal disabilities; work loss due to back pain in the UK is approximately 52 million days per year (Box 19.3). Disability due to low back pain has reached epidemic proportions and treatment costs amount to 1% of the total NHS budget (Grady et al 2007).

The exact mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of chronic persistent pain are complex and to date remain unclear. Even after the original acute painful episode has healed, chronic pain may manifest, and in some instances presents with no initial physiological assault. Ko & Zhou (2004) suggest that chronic pain may follow injury or disease with rapid long-term changes occurring within the CNS, particularly if the acute episode was not effectively managed. Within the spinal cord a central mechanism exists known as ‘wind-up’, which has links to physiological hypersensitivity and hyperexcitability. Wind-up occurs when there are repeated, prolonged and sustained noxious stimuli which cause the dorsal horn cells to fire and transmit progressively increasing numbers of pain impulses (Wood 2008). More recently, it was considered that spinal cord glial (supportive) cells are involved in chronic persistent pain; glial cells regulate extracellular ions and neurotransmitters, and clear away debris. Therefore, the suggestion is that glial cells are potentially responsible for amplifying pain by releasing substances that stimulate the pain response.

During episodes of chronic pain sensitisation can occur; there is amplification and distortion of pain messages and the painful condition is out of proportion to the original injury (Field & Smith 2008). Furthermore, spinal cord sensitisation can result from chemical reactions which increase pain messages being forwarded to the brain. PNS sensitisation can result from inflammation which causes nociceptors to fire with greater intensity.

Chronic pain is generally subdivided into:

Chronic non-malignant pain

There is persuasive evidence, mainly from developed countries, which suggests that chronic pain is a widespread public health issue. Some community-based studies have found that between 15 and 25% of adults suffer from chronic pain at any given time, and this figure can increase to 50% in populations over 65 years of age (Brennan et al 2007). Chronic non-malignant pain can be caused by persistent tissue injury where a degenerative condition exists: 46.5% of the population have conditions which result in chronic pain (Elliot et al 1999). It is thought that chronic non-malignant pain involves physiological changes to pain processing in the CNS which results in pain memories and leads to conditions such as phantom pain following amputation.

![]() See website Critical thinking question 19.1

See website Critical thinking question 19.1

Chronic non-maligant pain can be as destructive as malignant pain, as eventually it impacts on the individual’s family and social life and employment (McCaffery & Beebe 1989). Furthermore, it leads to isolation, relationship difficulties and mental health problems including suicidal ideation.

Chronic malignant pain

Pain associated with cancer is rarely a presenting feature, but the person’s ‘cancer journey’ may begin with acute pain (nociceptive) resulting from diagnostic procedures, including surgery. If the cancer metastasises, the pain becomes chronic, involving nociceptive and neuropathic elements but also psychoemotional ones. There needs to be regular assessment and readjustment of treatment to meet the needs of the individual; this requires the skills of an MDT (see Chs 31, 33). The prevalence of cancer increases with age, and pain is one of the most distressing symptoms. Unfortunately, for many older people it is more likely that pain will be under-reported and undertreated.

Chronic pain and depression

may occur concomitantly as chronic pain may exacerbate depression and vice versa. A study by Gureje et al (1998) revealed that people living with chronic pain are four times more likely than those without to suffer from depression and anxiety, which is consistent with other statistics on pain as a risk factor for both conditions (Fishbain 1999) (Box 19.4). It is estimated that 28% of people attending pain clinics (see p. 569) have a well-defined affective illness and people may manifest depression during the course of a painful illness without having being depressed previously (Grady et al 2007). However, approximately half of all depressed people have pain. Atypical facial pain was a common presenting feature in 66% of a series of depressed women, and in a smaller proportion of both sexes tension headaches were the most common presenting feature of depression.

Box 19.4 Evidence-based practice

Pain disorder or the chronic pain syndrome is a specific syndrome characterised by:

Nociceptive pain

Nociceptive pain is the most common type of pain seen in clinical settings and may be somatic or visceral (see Figure 19.2, p. 555). Pain results from stimulation of nociceptors following tissue damage or inflammation, e.g. surgery, infection or trauma. Intense and ongoing stimulation of nociceptors increases the excitability of neurones in the spinal cord leading to central sensitisation.

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the PNS or CNS (IASP 1994). The damage to the PNS and CNS can be due to stroke, spinal cord injury, brachial plexus avulsion, herpes zoster (shingles) leading to post-herpetic neuralgia, or follow amputation.

Damage leads to the development of central sensitisation causing reorganisation of synapses in the spinal cord and hyperexcitability in the peripheral nerves, and as a result the individual experiences symptoms that are characteristic of neuropathic pain. This definition has attracted some criticism, being described as vague, particularly in relation to the term ‘dysfunction’ which blurs the distinction between neuropathic pain and other possible pain types that may arise from different underlying mechanisms (Backonja 2003). It has been observed that pain and other neurological symptoms due to PNS or CNS disease/injury present in very similar ways, and this observation has led to a group designation of neuropathic pain. This definition is based upon the presence of neurological disease; however, it is important to note that most disorders that involve the nociceptors responsive to thermal stimuli do not present with pain and would suggest that these people have conditions that are genetic in origin (Backonja 2003).

Depending on the exact cause it may manifest as:

Pain threshold

The pain threshold is ‘the least experience of pain which a subject can recognize’ (IASP 1994). Laboratory studies of pain have demonstrated that pain thresholds are fairly constant across the population. In other words, the vast majority of people agree on the point at which a sensation becomes painful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree