CHAPTER 30 Nursing the patient with burn injury

Prevention of burn injuries

Burns are frequently described as being among the most serious of injuries because of the long-term problems which are often associated with them. Advances in treatment and improved facilities have led to a reduction in mortality rates (Pereira et al 2004), but the resultant morbidity is such that prevention is the responsibility of all health care personnel.

Studies emphasise that, in order to be effective, burn prevention programmes should involve assessment of the incidence of burn injuries, followed by planning, implementation and evaluation of appropriate interventions (Liao & Rossignol 2000).

Assessment

The extent of the problem

It is estimated that, in the UK, 112 000 people attend emergency departments annually suffering from the effects of burn injuries, with a further 250 000 presenting at GP services; approximately 7765 people require hospital admission and 211 people die each year as a result of burn injury (Benson et al 2006). Although statistical data on burn mortality are generally available, the incidence of burn morbidity is difficult to estimate.

Causative agents

The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (2003), previously responsible for collating fire statistics, identified the most common cause of death in domestic fires as careless handling of fire and hot substances, mainly smokers’ materials. Non-fatal burn casualties result from the misuse of equipment or appliances, most commonly cooking appliances. Hot water in plumbing systems is also a considerable cause for concern in countries where there is no legislation governing the upper limit of plumbed water temperature. Although many authorities advocate a temperature of 50°C (which would take 2–3 min to cause a burn), because of altered sensation and reduced mobility in older people, this figure has been reduced to 43°C in residential accommodation for older people (Stone et al 2000).

Predisposing factors

Epidemiological studies identify toddlers as being at greatest risk of burn injuries, with scalds accounting for most of these (Tse et al 2006). Adult high-risk groups include those with epilepsy (Unglaub et al 2005) and those who smoke tobacco, drink alcohol in excess and take prescribed psychotropic medications (Anwar et al 2005). Older people have also been identified as being more susceptible to burn injury and as having a higher mortality rate following injury (DeSanti 2005). Studies agree that males of all ages are at higher risk than females.

Planning and implementation

There are already numerous health education/promotion campaigns aimed at persuading the public not to smoke and to only drink alcohol in moderation. It seems unlikely that those who do not comply would be influenced by the knowledge that smoking and drinking alcohol increase their risk of burn injuries. Tones and Tilford (2001) state that, unlike the promotion of commercial products, which is based on enhancing pleasure and promising immediate gratification, health promotion usually urges people to stop doing something which they find pleasurable in the hope of long-term benefit. They also state that people have a right not to be unreasonably frightened. Blatant shock tactics are therefore considered unacceptable and are likely to make people ‘switch off’. More subtle, but potentially potent, messages may be conveyed, e.g. by incidental reference in popular television series.

Health care workers, therefore, not only have a responsibility to disseminate information on the prevention of burn injuries, but also must work closely with other interested groups such as the Fire Service, The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (Useful websites) and both local and national government in order to lobby for more effective legislation and regulations (Box 30.1). Nurses working in the community have the opportunity to observe the environment and to give specific advice relating to burns prevention.

Box 30.1 Reflection

Reducing burn injuries

Activity

First aid treatment of burns

Frequently, there is a continuing source of heat if the individual’s clothing is on fire or saturated by a hot liquid. The most effective way to remove this continuing heat source is to throw cool liquid, which is neither flammable nor corrosive, over the affected material, thus dousing the flames or reducing the temperature of the scalding liquid. If no such cool liquid is immediately to hand, rapid removal of hot saturated clothing will arrest the heat transfer. Where clothing is on fire, it is important to stop the person running around as this will fan the flames. The person assisting should lie the victim on the ground and use heavy material such as a coat or blanket to smother the flames. If chemicals are the causative agent, prompt sluicing with copious amounts of water will dilute the strength of the agent and limit the penetration of the chemical into the skin, where it will continue to cause damage for many hours. Hojer et al (2002) demonstrate the advantage of taking this universal first aid measure rather than taking time searching for specific neutralising agents. In the clinical situation, a useful means of identifying whether a chemical is acid or alkaline is to apply a urine testing strip, as this will give a pH reading.

After removal of the heat source from the skin, the next measure is to cool the superheated tissues. The easiest means of doing this is to place the affected part in cold water. For the face, however, cold soaks should be applied. The application of ice or chilled water below 8°C is contraindicated, as Venter et al (2007) found that this was associated with increased likelihood of tissue damage. There is no doubt that continued cooling reduces pain from the burn wound, but if a large area of the body surface is involved there is a risk of hypothermia.

Many burns units in the UK are now advising that the temporary wound dressing of choice is polyvinyl chloride film, e.g. cling film (Hudspith & Rayatt 2004). The reasons for this are:

To summarise, first aid treatment of burn injuries consists of:

Assessing the severity of burn injuries

The majority of patients with burn injuries do not require hospitalisation. The UK National Burn Injury Referral Guidelines (2001) recommend that when deciding whether to refer patients to a burn unit, consideration should be given to the complexity of the burn injury rather than simply to the size of the burn wound. The categories of patients for whom admission or referral to a regional burns unit is advisable include those:

Assessment of the severity of the burn injury involves estimation of the:

Extent of burn

Whenever tissues are traumatised, the inflammatory response occurs, resulting in increased circulation to the area (hyperaemia) and increased movement of fluids from intravascular to interstitial compartments. If this occurs in a small area, i.e. over less than 5% of the body surface, the effects are localised. However, when a larger percentage of the body surface is injured, there is a massive shift of fluids into the tissues with a corresponding reduction in circulating volume. It is generally accepted that children with burns involving more than 10%, and adults with burns of more than 15%, of body surface area will suffer from hypovolaemic shock unless there is prompt intravenous replacement of fluid (see Ch. 18).

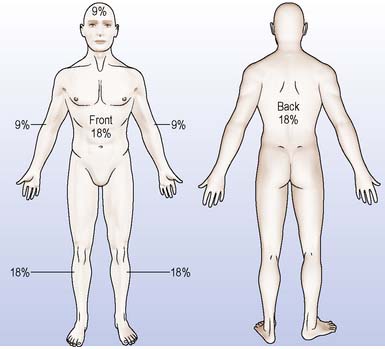

In order to estimate the percentage of body surface affected, the simplest and most easily remembered method is the long established ‘rule of nines’ introduced by Wallace in 1951 (Figure 30.1). In this method, the head and upper limbs each equal 9%, while the anterior trunk, the posterior trunk and the lower limbs each equal 18%. The remaining 1% is usually applied to the perineum. Another rapid approximation of the percentage can be made by using the palmar aspect of the patient’s hand (with fingers together) as 1% of the body surface area.

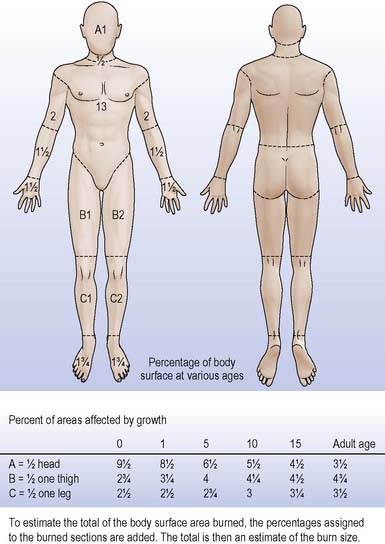

The rule of nines should never be used for estimating burn percentage in young children as it does not allow for the different proportions of head and lower limbs in infants and toddlers. Under the age of 1 year the child’s head equals 19% of the body surface area and the lower limbs are correspondingly smaller. A more accurate chart which allows for the changing proportions of different age groups and which shows percentages applicable to smaller, more specific areas of the body surface is the Lund and Browder (1944) burn chart (Figure 30.2). This is generally in use in specialist units and is available in EDs throughout the UK.

Burn depth

![]() See website Figures 30.1 and 30.2

See website Figures 30.1 and 30.2

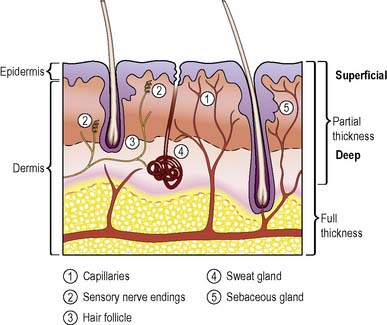

As may be seen from Figure 30.3, the more superficial the injury, the greater the number of surviving epithelial sources from which cells migrate across the wound surface; thus a more superficial burn heals more rapidly and causes less wound contraction. The effects of superficial partial-thickness burns and full-thickness burns are described below and in Table 30.1.

Table 30.1 Indications of burn depth

| Depth | Signs and Symptoms | Related Anatomy/Physiology |

|---|---|---|

| Superficial partial-thickness burns | Very painful | Sensory nerve endings in the dermis are stimulated by the injury and/or exposed to air |

| Oedema, blister formation, serous exudate where blisters have burst | As a result of the inflammatory response, the capillary walls are more permeable and fluid leaks into the interstitial spaces of the dermis, collecting below the non-germinating layers of the epidermis or exuding from the wound surface | |

| Wound surface warmer than unburned skin | Also due to the inflammatory response; arteriolar dilatation causes increased blood flow | |

| Wound appears bright pink and blanches with pressure | Due to increased blood flow Pressure greater than capillary blood pressure occludes the flow of blood | |

| Full-thickness burns | Painless, no sensation | Sensory nerve endings in the dermis are destroyed |

| Wound surface dry. No blistering | Cessation of blood flow through dermal capillaries | |

| No overt oedema | Necrosis of dermis renders it inelastic | |

| Wound surface cooler than unburned skin | Cessation of blood flow through dermal capillaries | |

| Wound colour may be white, brown, translucent showing thrombosed vessels, or bright red (does not blanch on pressure) | Cessation of blood flow through dermal capillaries. Brown or red appearance is caused by release of haem pigments from the destroyed erythrocytes (red blood cells) |

Problems in assessment

The assessment of burn depth is an inexact science, although much work has been carried out to make it more exact in recent years. The use of a hypodermic needle to test for pinprick sensation was first described by Bull and Lennard-Jones (1949). More recently, McGill et al (2007) found that both laser Doppler imaging and video microscopy may be used successfully in aiding assessment of burn depth; however, these options are not readily available outwith specialist burn units. Frequently, assessment of burn depth is dependent on the visual characteristics of the wound, the information regarding the circumstances of the accident, the agent involved and the first aid measures carried out.

Burn-associated respiratory tract injury

Inhibition of respiratory function may result from thermal injury to the skin of the trunk and neck. Hidden oedema formation below the leathery, inelastic eschar of circumferential full-thickness burns causes pressure on the deeper structures. In deep burns of the neck, this may cause compression of the trachea and, if there is involvement of the chest and upper abdomen, will inhibit expansion of the thoracic cavity. Decompression by escharotomy will be required (Box 30.2).

Box 30.2 Reflection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree