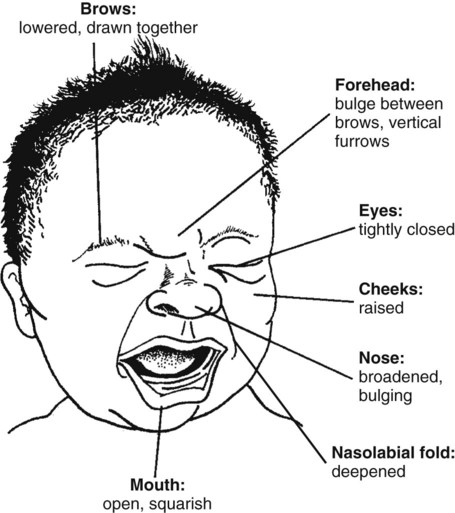

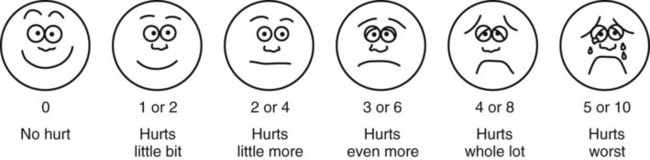

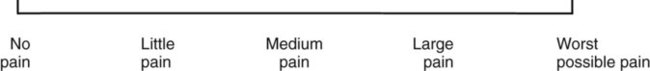

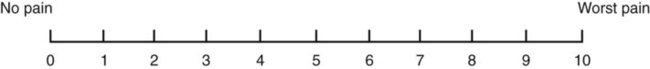

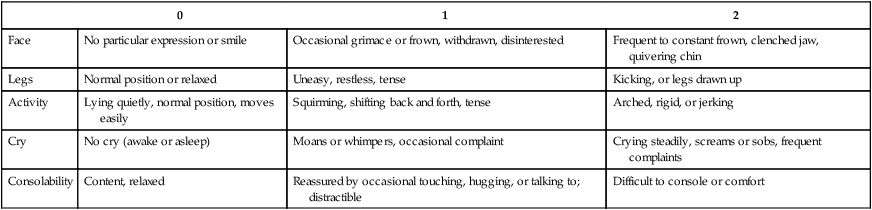

• The preterm infant’s response may be behaviorally blunted or absent, however there is sufficient evidence that preterm infants are neurologically capable of experiencing pain. • Use a preterm infant pain scale. • Assume that painful procedures in older child and adult are also painful in preterm infant (e.g., venipuncture, lumbar puncture, endotracheal intubation, circumcision, chest tube insertion, heel puncture). • Generalized body response of rigidity or thrashing, possibly with local reflex withdrawal of stimulated area (Figure 3-1) • Facial expression of pain (brows lowered and drawn together, eyes tightly closed, and mouth open and squarish) • No association demonstrated between approaching stimulus and subsequent pain • Verbal expressions such as “Ow,” “Ouch,” or “It hurts” • Attempts to push stimulus away before it is applied • Lack of cooperation; need for physical restraint • Requests termination of procedure • Clings to parent, nurse, or other significant person • Requests emotional support, such as hugs or other forms of physical comfort • May become restless and irritable with continuing pain • Behaviors occurring in anticipation of actual painful procedure • May see all behaviors of young child, especially during actual painful procedure, but less in anticipatory period • Stalling behavior, such as “Wait a minute” or “I’m not ready” • Muscular rigidity, such as clenched fists, white knuckles, gritted teeth, contracted limbs, body stiffness, closed eyes, wrinkled forehead TABLE 3-1 Behavioral Pain Assessment Scales for Infants and Young Children TABLE 3-2 From Merkel S and others: The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children, Pediatr Nurs 23(3):293-297, 1997. Used with permission of Jannetti Publications, Inc., and the University of Michigan Health System. Can be reproduced for clinical and research use. TABLE 3-3 Pain Rating Scales for Children Beyer JE, Denyes MJ, Villarruel AM: The creation, validation and continuing development of the Oucher: a measure of pain intensity in children, J Pediatr Nurs 7(5):335-346, 1992. Cline ME, Herman J, Shaw ER, and others: Standardization of the visual analogue scale, Eland JA, Banner W: Analgesia, sedation, and neuromuscular blockage in pediatric critical care. In Hazinski ME, editor: Manual of pediatric critical care, St Louis, 1999, Mosby. Hester NO, Foster RL, Jordan-Mash M, and others: Putting pain measurement into clinical practice. In Finley GA, McGrath PJ, editors: Measurement of pain in infants and children, vol 10, Seattle, 1998, International Association for the Study of Pain Press. Jordan-Marsh M, Yoder L, Hall D, and others: Alternate Oucher form testing: Gender ethnicity, and age variations, Res Nurs Health 17(2):111-118, 1994. Luffy R, Grove SK: Examining the validity, reliability, and preference of three pediatric pain measurement tools in African-American children, Pediatr Nurs 29(1):54-60, 2003. Tesler MD, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, and others: The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity, Res Nurs Health 14(5):361-371, 1991. Villarruel AM, Denyes MJ: Pain assessment in children: Theoretical and empirical validity, Adv Nurs Sci 14(2):32-41, 1991. Wong DL, Baker CM: Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales, Pediatr Nurs 14(1):9-17, 1988. Beyer JE, Denyes MJ, Villarruel AM: The creation, validation and continuing development of the Oucher: a measure of pain intensity in children, J Pediatr Nurs 7(5):335-346, 1992. Cline ME, Herman J, Shaw ER, and others: Standardization of the visual analogue scale, Nurs Res 41(6):378-380, 1992. Eland JA, Banner W: Analgesia, sedation, and neuromuscular blockage in pediatric critical care. In Hazinski ME, editor: Manual of pediatric critical care, St Louis, 1999, Mosby. Hester NO, Foster RL, Jordan-Mash M, and others: Putting pain measurement into clinical practice. In Finley GA, McGrath PJ, editors: Measurement of pain in infants and children, vol 10, Seattle, 1998, International Association for the Study of Pain Press. Jordan-Marsh M, Yoder L, Hall D, and others: Alternate Oucher form testing: Gender ethnicity, and age variations, Res Nurs Health 17(2):111-118, 1994. Luffy R, Grove SK: Examining the validity, reliability, and preference of three pediatric pain measurement tools in African-American children, Pediatr Nurs 29(1):54-60, 2003. Tesler MD, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, and others: The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity, Res Nurs Health 14(5):361-371, 1991. Villarruel AM, Denyes MJ: Pain assessment in children: Theoretical and empirical validity, Adv Nurs Sci 14(2):32-41, 1991. Wong DL, Baker CM: Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales, Pediatr Nurs 14(1):9-17, 1988. *Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale reference manual describing development and research of the scale is available from City of Hope Pain/Palliative Care Resource Center, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010; 626-359-8111, ext. 3829; fax: 626-301-8941; www1.us.elsevierhealth.com/FACES. †Instructions for Word-Graphic Rating Scale from Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management in infants, children, and adolescents: operative and medical procedures; quick reference guide for clinicians, ACHPR Pub. No. 92-0020, Rockville, Md, 1992, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. Word-Graphic Rating Scale is part of the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool and is available from Pediatric Pain Study, University of California, School of Nursing, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, Scan Francisco, CA 94143-0606; 415-476-4040. TABLE 3-4 CRIES Neonatal Postoperative Pain Scale Use nonpharmacologic interventions to supplement, not replace, pharmacologic interventions, and use for mild pain and pain that is reasonably well controlled with analgesics. Form a trusting relationship with child and family. Express concern regarding their reports of pain, and intervene appropriately. Use general guidelines to prepare child for procedure. Prepare child before potentially painful procedures, but avoid “planting” the idea of pain. For example, instead of saying, “This is going to (or may) hurt,” say, “Sometimes this feels like pushing, sticking, or pinching, and sometimes it doesn’t bother people. Tell me what it feels like to you.” Use “nonpain” descriptors when possible (e.g., “It feels like heat” rather than “It’s a burning pain”). This allows for variation in sensory perception, avoids suggesting pain, and gives the child control in describing reactions. Avoid evaluative statements or descriptions (e.g., “This is a terrible procedure” or “It really will hurt a lot”). Stay with child during a painful procedure. Allow parents to stay with child if child and parent desire; encourage parent to talk softly to child and to remain near child’s head. Involve parents in learning specific nonpharmacologic strategies and in assisting child with their use. Educate child about the pain, especially when explanation may lessen anxiety (e.g., that pain may occur after surgery and does not indicate something is wrong); reassure the child that he or she is not responsible for the pain. For long-term pain control, give child a doll, which represents “the patient,” and allow child to do everything to the doll that is done to the child; pain control can be emphasized through the doll by stating, “Dolly feels better after the medicine.” Involve parent and child in identifying strong distracters. Involve child in play; use radio, tape recorder, CD player, or computer game; have child sing or use rhythmic breathing. Have child take a deep breath and blow it out until told to stop. Have child blow bubbles to “blow the hurt away.” Have child concentrate on yelling or saying “ouch,” with instructions to “yell as loud or soft as you feel it hurt; that way I know what’s happening.” Have child look through kaleidoscope (type with glitter suspended in fluid-filled tube) and encourage him or her to concentrate by asking, “Do you see the different designs?” Use humor, such as watching cartoons, telling jokes or funny stories, or acting silly with child. With an infant or young child: Hold in a comfortable, well-supported position, such as vertically against the chest and shoulder. Rock in a wide, rhythmic arc in a rocking chair or sway back and forth, rather than bouncing child. Ask child to take a deep breath and “go limp as a rag doll” while exhaling slowly; then ask child to yawn (demonstrate if needed). Help child assume a comfortable position (e.g., pillow under neck and knees). Begin progressive relaxation: starting with the toes, systematically instruct child to let each body part “go limp” or “feel heavy”; if child has difficulty relaxing, instruct child to tense or tighten each body part and then relax it. Allow child to keep eyes open, since children may respond better if eyes are open rather than closed during relaxation. Have child identify some highly pleasurable real or imaginary experience. Have child describe details of the event, including as many senses as possible (e.g., “feel the cool breezes,” “see the beautiful colors,” “hear the pleasant music”). Have child write down or tape-record script. Encourage child to concentrate only on the pleasurable event during the painful time; enhance the image by recalling specific details through reading the script or playing the tape. Identify positive facts about the painful event (e.g., “It does not last long”). Identify reassuring information (e.g., “If I think about something else, it does not hurt as much”). Condense positive and reassuring facts into a set of brief statements, and have child memorize them (e.g., “Short procedure, good veins, little hurt, nice nurse, go home”). Have child repeat the memorized statements whenever thinking about or experiencing the painful event. Informal—May be used with children as young as four or five years of age: Use stars, tokens, or cartoon character stickers as rewards. Give a child who is uncooperative or procrastinating during a procedure a limited time (measured by a visible timer) to complete the procedure. Proceed as needed if child is unable to comply. Reinforce cooperation with a reward if the procedure is accomplished within specified time. Formal—Use written contract, which includes the following: Realistic (seems possible) goal or desired behavior Measurable behavior (e.g., agrees not to hit anyone during procedures) Contract written, dated, and signed by all persons involved in any of the agreements Identified rewards or consequences that are reinforcing Commitment and compromise requirements for both parties (e.g., while timer is used, nurse will not nag or prod child to complete procedure) Oral route preferred because of convenience, cost, and relatively steady blood levels Higher dosages of oral form of opioids required for equivalent parenteral analgesia Peak drug effect occurs after 1 to 2 hours for most analgesics Delay in onset a disadvantage when rapid control of severe pain or of fluctuating pain is desired In young infants, oral sucrose can provide analgesia for painful procedures.

Pain Assessment and Management

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia

Children’s Response to Pain

Developmental Characteristics of Children’s Responses to Pain

Preterm Infant

Young Infant

Young Child

School-Age Child

Adolescent

Ages of Use

Instrument

4 months to 18 years

Objective Pain Score (OPS) (Hannallah and others, 1987)

1 to 5 years

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) (McGrath and others, 1985)

Newborn to 16 years

Nurses Assessment of Pain Inventory (NAPI) (Stevens, 1990)

3 to 36 months

Behavioral Pain Score (BPS) (Robieux and others, 1991)

4 to 6 months

Modified Behavioral Pain Scale (MBPS) (Taddio and others, 1995)

<36 months and children with cerebral palsy

Riley Infant Pain Scale (RIPS) (Schade and others, 1996)

2 months to 7 years

FLACC Postoperative Pain Tool (Merkel and others, 1997)

1 to 7 months

Postoperative Pain Score (POPS) (Attia and others, 1987)

Average gestational age 33.5 weeks

Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) (Lawrence and others, 1993)

27 weeks gestational age to full term

Pain Assessment Tool (PAT) (Hodgkinson and others, 1994)

1 to 36 months

Pain Rating Scale (PRS) (Joyce and others, 1994)

32 to 60 weeks gestational age

CRIES (Krechel, Bildner, 1995)

28 to 40 weeks gestational age

Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP) (Stevens and others, 1996)

0 to 28 days

Scale for Use in Newborns (SUN) (Blauer, Gerstmann, 1998)

Birth (23 weeks gestational age) and full-term newborns up to 100 days

Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale (NPASS) (Puchalski, Hummel, 2002)

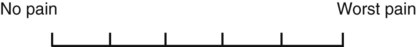

0

1

2

Face

No particular expression or smile

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested

Frequent to constant frown, clenched jaw, quivering chin

Legs

Normal position or relaxed

Uneasy, restless, tense

Kicking, or legs drawn up

Activity

Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily

Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense

Arched, rigid, or jerking

Cry

No cry (awake or asleep)

Moans or whimpers, occasional complaint

Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints

Consolability

Content, relaxed

Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or talking to; distractible

Difficult to console or comfort

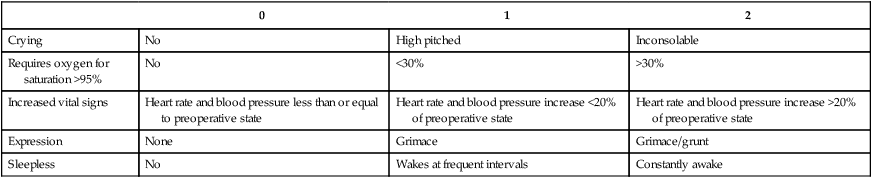

0

1

2

Crying

No

High pitched

Inconsolable

Requires oxygen for saturation >95%

No

<30%

>30%

Increased vital signs

Heart rate and blood pressure less than or equal to preoperative state

Heart rate and blood pressure increase <20% of preoperative state

Heart rate and blood pressure increase >20% of preoperative state

Expression

None

Grimace

Grimace/grunt

Sleepless

No

Wakes at frequent intervals

Constantly awake

Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Pain Management

![]() General Strategies

General Strategies

Specific Strategies

Distraction

Relaxation

Guided Imagery

Thought Stopping

Behavioral Contracting

Analgesic Drug Administration

Routes and Methods

Oral

Pain Assessment and Management

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access