Pain and its management

Understanding pain

♦ Pain is a subjective experience unique to the person experiencing it. Any report of pain must be investigated and addressed.

♦ The Joint Commission has designated pain level as “the fifth vital sign.” Nurses are required to determine each patient’s pain on admission, with each shift assessment, and as needed.

♦ Pain has a sensory component and a reaction component.

– The sensory component involves an electrical impulse that travels to the central nervous system, where it’s perceived as pain.

– The response to this perception is the reaction component.

♦ Pain may be acute, chronic, or both. (See Differentiating acute and chronic pain.)

– Acute pain is caused by tissue damage from injury, disease, or surgical or diagnostic procedures. It varies in intensity from mild to severe and lasts briefly. It’s considered a protective mechanism because it warns of current or potential tissue damage or organ disease.

Differentiating acute and chronic pain

Acute pain may cause certain physiologic and behavioral changes that you won’t observe in a patient with chronic pain.

TYPE OF PAIN | PHYSIOLOGIC EVIDENCE | BEHAVIORAL EVIDENCE |

Acute | ♦ Increased respirations ♦ Increased pulse ♦ Increased blood pressure ♦ Dilated pupils ♦ Diaphoresis | ♦ Restlessness ♦ Distraction ♦ Worry ♦ Distress |

Chronic | ♦ Normal respirations, pulse, blood pressure, and pupil size ♦ No diaphoresis | ♦ Reduced or absent physical activity ♦ Despair or depression ♦ Hopelessness |

– Chronic pain is pain that has lasted 6 months or longer and is ongoing. Although it may be as intense as acute pain, it isn’t a warning of tissue damage.

♦ It’s important for you to understand how pain is determined.

♦ The most valid identification of pain comes from the patient’s own reports. (See PQRST: The alphabet of pain identification, page 370.)

♦ Many pain identification tools are available. The chosen tool should be used consistently when addressing the patient’s pain.

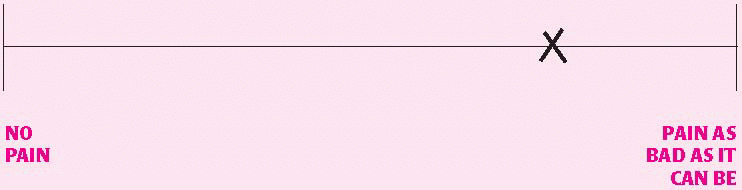

♦ The three most common pain identification tools used by clinicians are the visual analog scale (see Visual analog scale, page 370), the numeric rating scale (see Numeric rating scale, page 371), and the FACES scale (see Wong-Baker FACES scale, page 371).

PQRST: The alphabet of pain identification

The PQRST mnemonic device is commonly used to obtain more information about the patient’s pain. It includes the following questions to help elicit important details.

Provocative or palliative

♦ What provokes or worsens your pain?

♦ What relieves your pain or causes it to subside?

Quality or quantity

♦ What does the pain feel like? For example, is it aching, intense, knifelike, burning, or cramping?

♦ Are you having pain right now? If so, is it more or less severe than usual?

♦ To what degree does the pain affect your normal activities?

♦ Do you have other symptoms along with the pain, such as nausea or vomiting?

Region and radiation

♦ Where is your pain?

♦ Does the pain radiate to other parts of your body?

Severity

♦ How severe is your pain? How would you rate it on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable?

♦ How would you describe the intensity of your pain at its best? At its worst? Right now?

Timing

♦ When did your pain begin?

♦ At what time of day is your pain least? At what time of day is it greatest?

♦ Is the onset sudden or gradual?

♦ Is the pain constant or intermittent?

Numeric rating scale

A numeric rating scale can help the patient quantify his pain. To use this scale, the patient chooses a number from 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (indicating the worst pain imaginable) to reflect his current level of pain. He can either circle the number on the scale or state the number that best describes his pain.

NO PAIN | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | PAIN AS BAD AS IT CAN BE |

Wong-Baker FACES scale

A child or an adult with language difficulties may not be able to express the pain he’s feeling. In such instances, a pain intensity scale such as the one shown below may be helpful. To use this scale, the patient chooses the face that best represents the severity of his pain.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Alternate coding: | No hurt 0 | Hurts little bit 2 | Hurts little more 4 | Hurts even more 6 | Hurts whole lot 8 | Hurts worst 10 |

From Hockenberry, M.J., Wilson, D.: Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 8th ed. St. Louis, 2009, Mosby. Used with permission. Copyright Mosby.

♦ Pain may cause many physiological and psychological responses; watch carefully for them whenever you care for the patient. (See Pain behavior checklist, page 372.)

Understanding pain management drugs

♦ Adequate pain control depends on effective identification and interventions, including drug therapy. To provide the best care possible, work with physicians and other members of the health care team to carry out an individualized pain management program for each patient.

♦ Drug classes commonly used for pain management include:

– nonopioids

– opioids

– antidepressants.

♦ Nonopioids are the first choice for managing mild pain. They decrease pain by inhibiting inflammation at the injury site or by blocking the entrance

of pain signals to the brain. Examples of nonopioids are:

of pain signals to the brain. Examples of nonopioids are:

Pain behavior checklist

A patient often communicates pain, distress, or suffering through pain behaviors. Place a check in the box next to each behavior that you observe or infer while talking with the patient.

▪ Grimacing

▪ Moaning

▪ Sighing

▪ Clenching the teeth

▪ Holding or supporting the painful body area

▪ Sitting rigidly

▪ Shifting posture or position often

▪ Moving in a guarded or protective manner

▪ Moving very slowly

▪ Taking medication

▪ Using a cane, a cervical collar, or another prosthetic device

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access