Chapter 14

Outcomes Research

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Explain the theoretical basis of outcomes research.

2. Discuss the history of outcomes research in nursing.

3. Describe the role of outcomes research in determining the effect of nursing on health outcomes.

4. Differentiate outcomes research from other types of research conducted by nurses.

5. Identify the methodologies used in published outcomes studies.

Administrative databases, p. 483

Nurse’s role in outcomes, p. 470

Nursing Care Report Card, p. 474

Nursing-sensitive patient outcome, p. 471

Patient health outcomes, p. 473

Population-based studies, p. 487

Prospective cohort study, p. 484

Retrospective cohort study, p. 485

Standardized mortality ratio (SMR), p. 486

Outcomes research, now an established field of health research, focuses on the end results of patient care. More specifically, outcomes research is concerned with the effectiveness of healthcare interventions and health services (Doran, 2011; Jefford, Stockler, & Tattersall, 2003). In the context of nursing, it focuses on how a patient’s health status changes as a result of the nursing care received or the nursing services delivered. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggests that “outcomes research seeks to understand the end results of particular healthcare practices and interventions. End results include effects that people experience and care about, such as change in the ability to function. In particular, for individuals with chronic conditions, where cure is not always possible, end results include quality of life as well as mortality. By linking the care people receive to the outcomes they experience, outcomes research has become the key to developing better ways to monitor and improve quality of care” (AHRQ, 2013).

Theoretical Basis of Outcomes Research

The theorist Avedis Donabedian (1976, 1978, 1980, 1982, 1987) proposed a theory of quality health care and provided a process for evaluating it. Donabedian’s theory still dominates outcomes research. Other theories of outcomes have since been developed, but we will limit our discussion to Donabedian’s theory. Although quality is the overriding construct of Donabedian’s theory, he never actually defined this concept himself (Mark, 1995). The World Health Organization (WHO; 2009, p. 13) defined quality of care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”

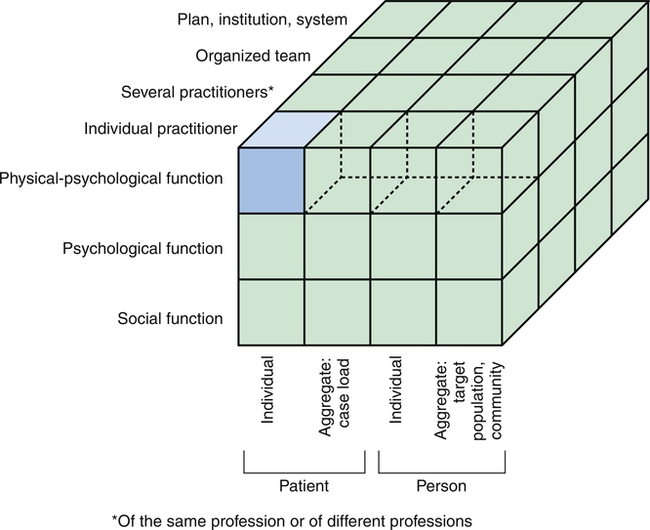

Donabedian (1987) represented the key concepts and relationships in his theory using a cube. The cube shown in Figure 14-1 helps explain the elements of quality health care. The three dimensions of the cube are health, the subjects of care, and the providers of care. The cube also incorporates three of the many aspects of health—physical-psychological function, psychological function, and social function. Donabedian (1987, p. 4) proposed that “the manner in which we conceive of health, and of our responsibility for it, makes a fundamental difference to the concept of quality and, as a result, to the methods that we use to assess and assure the quality of care.”

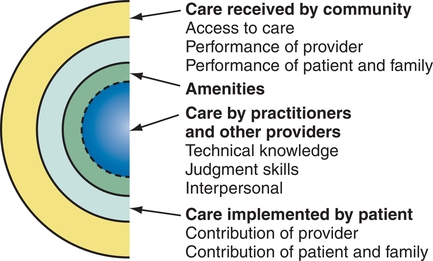

Loegering, Reiter, and Gambone (1994) modified Donabedian’s levels to include the patient, patient’s family, and community as providers as well as recipients of care. They suggest that access to care is one dimension of the provision of care by the community. Figure 14-2 illustrates their modifications.

Donabedian (1987, 2005) identified three foci of evaluation in appraising quality—structure (e.g., nursing units, hospitals, home health agencies), process (of how care is provided, such as a practice style or standard of care), and outcomes (end results of care). Each of these constructs is addressed in this chapter. A complete quality assessment program requires the simultaneous inclusion of all three and an examination of the relationships among them. However, researchers have had little success in accomplishing this theoretical goal. Studies designed to examine all three constructs would require sufficiently large samples of various structures, each with the various processes being compared and large samples of subjects who have experienced the outcomes of those processes. The funding required and cooperation necessary to accomplish this goal have not yet been realized; however, there are examples of nursing research in which two or more aspects have been evaluated. Numerous studies conducted by nurses in the United States (Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008; Kutney-Lee, Sloane, & Aiken, 2013; Stone, Mooney-Kane, Larson, Horan, Glance, Zwanziger, et al., 2007; Yoder, Xin, Norris, & Yan, 2013), Canada (Doran et al., 2006a, 2006b; Doran, Sidani, Keatings, & Doidge, 2002; McGillis Hall et al., 2003; Tourangeau, 2003; Tourangeau et al., 2007), and internationally (Bakker et al., 2011; Oh, Park, Jin, Piao, & Lee, 2013; Van den Heede, et al., 2009) have explored the relationships among nursing interventions, nursing services, and patient outcomes. Nursing interventions reflect the care delivered by nurses. A falls risk assessment or pressure ulcer risk assessment are examples of nursing interventions. Nursing services is a general concept referring to the organization and administration of nursing activities. Nursing service variables that have been studied include the skill mix and configuration of nursing personnel; staffing levels; assignment patterns (primary, functional, or team); shift patterns; levels of nursing education, experience, and expertise; ratios of full-time to part-time nurses; level and type of nursing leadership available centrally and on units; cohesion and communication among the nursing staff and between nurses and physicians; implementation of clinical care maps for patients with selected diagnoses; and the interrelationships of these factors.

Nursing-Sensitive Outcomes

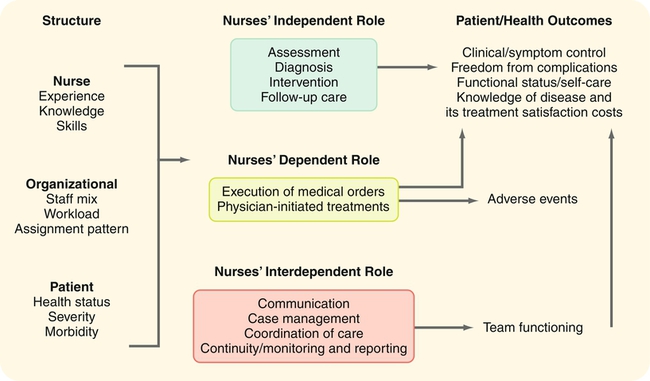

Irvine, Sidani, and McGillis Hall (1998) adapted Donabedian’s (1987) theory of quality in their development of the Nursing Role Effectiveness Model. The Nursing Role Effectiveness Model, presented in Figure 14-3, was developed to guide conceptualization and research related to nursing-sensitive outcomes. It also provided the theoretical basis for a systematic review of the “state of the science on nursing-sensitive outcomes measurement” (Doran, 2011). The Nursing Role Effectiveness Model is based on Donabedian’s (1987) quality framework and has three major components—structure, the nurses’ role, and patient and health outcomes. Structure in outcomes has three subcomponents—nurse, organization, and patient. Nurse variables that influence the quality of nursing care include factors such as experience level, knowledge, and skill level. Organizational components that can affect the quality of nursing care include staff mix, workload, and assignment patterns. Patient characteristics that can affect the quality of care and outcomes include health status, severity, and morbidity. The nurse’s role in outcomes has three subcomponents— nurse’s independent role, nurse’s dependent role, and nurse’s interdependent role. Independent role functions include assessment, diagnosis, nurse-initiated interventions, and follow-up care. The patient and health outcomes of the independent role are clinical and symptom control, freedom from complications, functional status and self-care, knowledge of disease and its treatment, satisfaction, and costs. The dependent role functions include execution of medical orders and physician-initiated treatments. It is the dependent role functions that can lead to patient and health outcomes of adverse events. Interdependent role functions include communication, case management, coordination of care, and continuity, monitoring, and reporting. The interdependent role results in team functioning and affects the patient and health outcomes of the independent role. Patient and health outcomes are clearly interwoven into the entire care context. The propositions of the Nursing Role Effectiveness Model are as follows (Irvine et al., 1998, p. 62):

• Nursing’s capacity to engage effectively in the independent, dependent, and interdependent role functions is influenced by individual nurse variables, patient variables, and organizational structure variables.

• The nurse’s interdependent role function depends on the ability to communicate and articulate her or his opinion to other members of the healthcare team.

• Nurse, patient, and system structural variables have a direct effect on clinical, functional, satisfaction, and cost outcomes.

• The nurse’s independent role function can have a direct effect on clinical, functional, satisfaction, and cost outcomes.

• Medication errors and other adverse events associated with the nurse’s dependent role function can ultimately affect all categories of patient outcome.

• Nursing’s interdependent role function can affect the quality of interprofessional communication and coordination, with the recognition that the nature of interprofessional communication and coordination can influence other important patient outcomes and costs, such as risk-adjusted length of stay, risk-adjusted mortality rates, excess home care costs following discharge, unplanned visits to the physician or emergency department, and unplanned rehospitalization.

The Nursing Role Effectiveness Model (see Figure 14-3) provided a framework for conceptualizing nursing-sensitive outcomes (Doran, 2011) and directed the selection of keywords that were used in the systematic review of the state of the science on nursing-sensitive outcomes measurement. The methodology and results of this systematic review are discussed next.

Conceptual and empirical research articles were included in the systematic review. Conceptual papers were included if they discussed the definition and domains of a patient outcome concept, or if they presented the results of a concept analysis designed to explicate the conceptual definition and dimensions of the outcome concept. Empirical papers were included if they described the development of an instrument to measure the outcome concept or evaluated the psychometric properties of the instrument. Papers that reported results of studies that examined the relationship among nursing structural variables, nursing interventions, and outcomes were included. The review focused on studies that were conducted in acute care, home care, primary care, and long-term care settings. For each empirical paper, the authors made note of the date of publication, study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT], case control, prospective cohort, or descriptive), setting, sample, response rate, and study limitations. This information was important for determining the generalizability of the study results to specific clinical contexts (i.e., external validity) and for determining threats to internal validity, such as response bias or the influence of confounding variables (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of types of design validity). A confounding variable is an extraneous variable whose presence affects the variables being studied so that the findings might not be an accurate reflection of reality. Researchers select study designs to reduce the effect of extraneous variables. The review also included information about the specific structural or nursing intervention variables and their relationships with the outcome variables examined.

One of the results of this systematic review was the identification of nurse-sensitive patient outcomes (Doran, 2011). A nursing-sensitive patient outcome (NSPO) is sensitive because it is influenced by nursing care decisions and actions. It may not be caused by nursing but is associated with nursing. In various situations, “nursing” might be the individual nurse, nurses as a working group, approach to nursing practice, nursing unit, or institution that determines the numbers of nurses, their salaries, educational levels of nurses, assignments of nurses, workload of nurses, management of nurses, and policies related to nurses and nursing practice. It might even include the architecture of the nursing unit. In whatever form, nursing actions have a role in the outcome, even though acts of other professionals, organizational acts, and patient characteristics and behaviors often are involved in the outcome. What patient outcomes can you think of that might be nursing-sensitive? Examples of nursing-sensitive outcomes from Doran and colleagues’ review and their definitions are summarized in Table 14-1.

Table 14-1

Nursing-Sensitive Patient Outcomes and Definitions

| Outcome Concept | Definition |

| Functional status | Functional status is a multidimensional construct that consists of, at least, behavioral (e.g., performance of activities of daily living), psychological (e.g., mood), cognitive (e.g., attention, concentration), and social (e.g., activities associated with roles) components (Knight, 2000; Doran, 2011). |

| Self-care | Self-care behavior entails the practice of actions or activities that individuals initiate and perform, within time frames, on their own behalf in the interest of maintaining life, healthy functioning, continued personal development, and well-being (Jenerette & Murdaugh, 2008; Orem, 2001; Sidani, 2011a). |

| Symptoms | “Symptoms refer to (a) sensations or experiences reflecting changes in a person’s biopsychosocial functions, (b) a patient’s perception of an abnormal physical, emotional, or cognitive state, (c) the perceived indicators of change in normal functioning, as experienced by patients, or (d) subjective experience reflecting changes in the biopsychosocial functioning, sensations, or cognition of an individual” (Sidani, 2011b, p. 132). |

| Pain | Pain has been defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (Merskey & Bogduk, 1994, p. 210). |

| Adverse outcome | An adverse outcome is defined as consequence of injury caused by medical management or complication rather than by the underlying disease itself, and generally includes prolonged health care, a resulting disability, or death at the time of discharge (WHO, 2009). |

| Psychological distress | Psychological distress has been defined as “the emotional condition that one feels in response to having to cope with situations that are unsettling, frustrating, or perceived as harmful or threatening” (Lazarus & Folman’s work as cited in Howell, 2011, p. 289). |

| Patient satisfaction | “Patient satisfaction is frequently defined as the extent to which patients’ expectations of care match the actual care received” (Spence Laschinger, Gilbert, & Smith, 2011, p. 362). |

| Mortality rate | Mortality, in its simplest meaning, reflects death. “When examining death as a quality-of-care outcome, rates of death are examined for specific patient samples or populations” (Tourangeau, 2011, p. 411). |

| Healthcare utilization | “Healthcare utilization can be thought of as the sum or aggregate of services consumed by patients in their attempts to maintain or regain a level of health status, along with the costs of these services” (Clarke, 2011, p. 441). |

Origins of Outcomes and Performance Monitoring

Florence Nightingale has been credited as being the first nurse to collect data to identify nursing’s contribution to quality care and conduct research into patient outcomes (Magnello, 2010; Montalvo, 2007). However, efforts to collect data systematically to assess outcomes in more modern times did not gain widespread attention in the United States until the late 1970s. At that time, concerns about quality of care prompted the development of the Universal Minimum Health Data Set, which was followed shortly thereafter by the Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (Kleib, Sales, Doran, Mallette, & White, 2011). These data sets facilitated consistency in data collection among healthcare organizations by prescribing the data elements to be gathered. The aggregated data were then used to perform an assessment of quality of care in hospitals and provide information on patients discharged from hospitals.

Over time, other countries developed similar data sets. In Canada, “Standards for Management Information Systems” (MIS) were developed in the 1980s. With the establishment of the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) in 1994, the MIS became a set of national standards used to collect and report financial and statistical data from health service organizations’ daily operations (CIHI, 2012). Simultaneously, CIHI implemented a national Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), which has become a key resource in outcomes research. However, those data sets did not include information about nursing care delivered to patients in the hospital (Kleib et al., 2011). Without that information, the contribution of nursing care to patient, organizational, and system outcomes was rendered invisible. This major gap in information was addressed by the development of nursing minimum data sets in the United States, Canada, and other countries worldwide.

Federal Government Involvement in Outcomes Research

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

The AHRQ, as a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), supports research designed to improve the outcomes and quality of health care, reduce healthcare costs, address patient safety and medical errors, and broaden access to effective services. The AHRQ website (http://www.ahrq.gov) is a valuable source of information about outcomes research, funding opportunities, and results of recently completed research, including nursing research. In 2010, the AHRQ was awarded $25 million in funding to support efforts by states and health systems to implement and evaluate patient safety approaches and medical liability reform models. In addition, AHRQ invested $17 million to expand projects to help prevent health care–associated infections (HAIs), the most common complication of hospital care. The AHRQ initiated several major research efforts to examine medical outcomes and improve quality of care. One of the most current initiatives is comparative effectiveness research, which is described in the next section.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

Funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act), signed into law in 2009, allowed AHRQ to expand its work in support of comparative effectiveness research, including enhancing the Effective Health Care Program. A total of $473 million was designated for funding patient-centered outcomes research (AHRQ, 2010). The AHRQ program provides patients, clinicians, and others with evidence-based information to make informed decisions about health care through activities such as comparative effectiveness reviews conducted through AHRQ’s Evidence-Based Practice Center (EPC). The AHRQ has a broad research portfolio that involves almost every aspect of health care, including:

National Quality Forum

The National Quality Forum (NQF) was created in 1999 as a national standard-setting organization for healthcare performance measures (NQF, 2013a). The NQF portfolio of voluntary consensus standards includes performance measures, serious reportable events, and preferred practices (i.e., safe practices). A complete list of measures included in the NQF portfolio can be found online (http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx). Approximately one third of the measures in NQF’s portfolio are measures of patient outcomes, such as mortality, readmissions, health functioning, depression, and experience of care. The NQF includes several nursing-sensitive measures in its performance measurement portfolio. Those that were submitted by the American Nurses Association (ANA) under the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (see later) include the following:

• Nursing hours per patient day

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI) rate

• Central line–associated bloodstream infection rate

• Hospital- and unit-acquired pressure ulcer rates

• RN practice environment scale

These indicators are the first nationally standardized performance measures of nursing-sensitive outcomes in acute care hospitals and are designed to assess healthcare quality, patient safety, and a professional and safe work environment. Although most of the measures in use focus on the failure to meet expected standards, the NQF believes that quality is as much about influencing positive outcomes as about avoiding negative outcomes. Therefore, the NQF is currently developing national standards to evaluate the quality of health care based on how patients feel. It notes that “national quality assessment programs usually measure and reward practices based on improving clinical processes such as re-hospitalization or infection rates. While this type of information is important and useful to clinicians, it doesn’t always take into account what is most important to the patient and families of the patient receiving care, such as the management of long-term symptoms or ability to conduct daily activities” (NQF, 2013b).

National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators

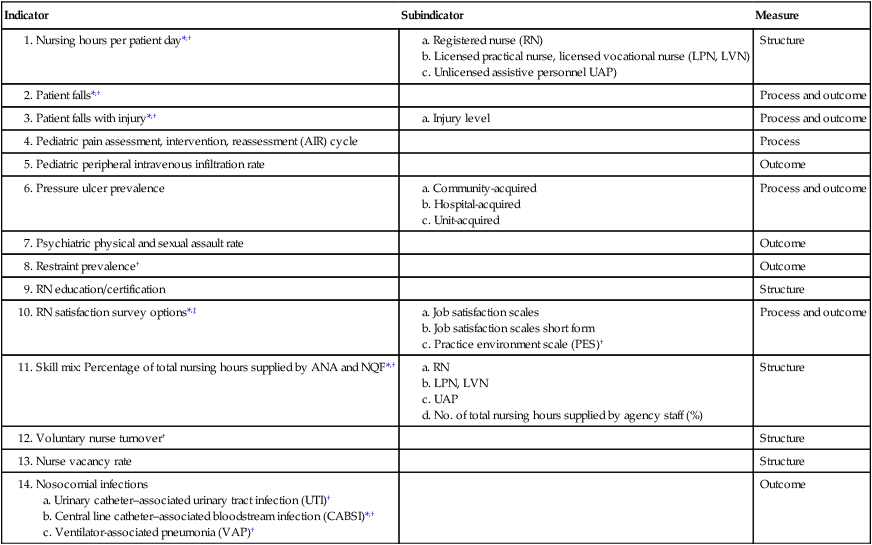

In 1994, the ANA, in collaboration with the American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care, launched a plan to identify indicators of quality nursing practice and collect and analyze data using these indicators throughout the United States (Mitchell, Ferketich, & Jennings, 1998). The goal was to identify and/or develop nursing-sensitive quality measures. Donabedian’s theory was used as the framework for the project. Together, these indicators were referred to as the ANA Nursing Care Report Card, which could facilitate benchmarking or setting a desired standard that would allow comparisons of hospitals in terms of their nursing care quality.

In 1998, the ANA provided funding to develop a national database to house data collected using nursing-sensitive quality indicators. This became the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI; Montalvo, 2007). Participation in NDNQI meets requirements for the Magnet Recognition Program, and 20% of database members participate for that reason (see Chapters 1 and 13 for a discussion of Magnet status). Detailed guidelines for data collection, including definitions and decision guides, are provided by the NDNQI (2013). The NDNQI nursing-sensitive indicators are summarized in Table 14-2.

Table 14-2

American Nurses Association National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators

| Indicator | Subindicator | Measure |

| Structure | ||

| Process and outcome | ||

| Process and outcome | ||

| Process | ||

| Outcome | ||

| Process and outcome | ||

| Outcome | ||

| Outcome | ||

| Structure | ||

| Process and outcome | ||

| Structure | ||

| Structure | ||

| Structure | ||

| Outcome |

*Original ANA nursing-sensitive indicator.

†NQF-endorsed nursing-sensitive indicator.

‡The RN survey is annual, whereas the other indicators are quarterly.

Other organizations currently involved in efforts to study nursing-sensitive outcomes include the Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes California Database (CALNOC, 2013a), Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Quality Initiative, American Hospital Association, the Federation of American Hospitals, The Joint Commission and, in Canada, the Canadian Nurses Association National Nursing Quality Report. For further information on these outcome initiatives, you can review Doran, Mildon, and Clarke’s (2011) knowledge synthesis of the state of science on nursing outcomes measurement and international nursing report card initiatives. This knowledge synthesis was a review of nursing-sensitive outcome and report card initiatives in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Belgium.

Oncology Nursing Society

The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS, 2012) is a professional organization of more than 35,000 RNs and other healthcare providers dedicated to excellence in patient care, education, research, and administration in oncology nursing. The ONS has taken a leadership role among specialty nursing organizations in developing an evidence-based practice (EBP) resource area on its website (http://www.ons.org/ClinicalResources). The site provides nurses with a guide to identify, critically appraise, and use evidence to solve clinical problems. The ONS website also assists nurses, in particular advanced practice nurses, who are helping others develop EBP protocols. The outcomes resource area is helpful to nurses for achieving desired outcomes for people with cancer by providing outcome measures, resource cards, and evidence tables.

Advanced Practice Nursing Outcomes Research

There is abundant research demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of APNs. DiCenso and colleagues (2010) conducted a search of all RCTs ever published, comparing APNs to usual care in terms of patient, provider, and/or health system outcomes. They found a total of 78 trials—28 of primary care NPs, 17 of acute care NPs, 32 of CNSs, and one of a combined CNS-NP role. Findings consistently showed that care by APNs resulted in equivalent or improved outcomes. Moore and McQuestion (2012) conducted a systematic review of the outcomes of the CNS role, focusing on chronic disease patient populations. Many of the studies showed that CNSs had a positive impact on patients living with chronic illnesses. Key outcomes included an improvement in quality of life, patient and health provider satisfaction, fewer and shorter rehospitalizations, and lower costs of care. Examples of outcomes that have been found to be sensitive to APN processes of care are summarized in Table 14-3.

Table 14-3

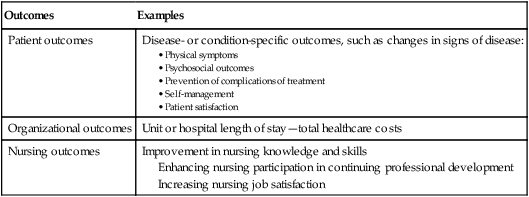

Outcomes Associated with Advanced Practice Nurses’ Processes of Care

| Outcomes | Examples |

| Patient outcomes | Disease- or condition-specific outcomes, such as changes in signs of disease: |

| Organizational outcomes | Unit or hospital length of stay—total healthcare costs |

| Nursing outcomes | Improvement in nursing knowledge and skills Enhancing nursing participation in continuing professional development Increasing nursing job satisfaction |

From Doran, D. M., Sidani, S., & Di Pietro, T. (2010). Nursing-sensitive outcomes. In J. S. Fulton, B. Lyon, & K. Goudreau (Eds.), Foundations of clinical nurse specialist practice (pp. 35-37). New York: Springer.

Outcomes Research and Nursing Practice

Outcome studies provide rich opportunities to build a stronger scientific underpinning for nursing practice. Nurse researchers have been actively involved in the effort to examine the outcomes of patient care. Ideally, we would like to understand the outcomes of nursing practice within a one to one nurse-patient relationship; however, in most cases, the nursing effect is shared because more than one nurse cares for a patient. In addition, nurse managers and nurse administrators have control over the nursing staff and the environment of nursing practice, and this control affects the autonomy of the nurse to implement practice. Consequently, outcomes research must first focus on how nursing care is organized, rather than on what nurses do. When that occurs, we may begin to determine how what nurses do influences patient outcomes (Lake, 2006). In the next section of this chapter, we provide a description of approaches to evaluating outcomes, structural variables, and processes of care.

Evaluating Outcomes of Care

The goal of outcomes research is the evaluation of outcomes as defined by Donabedian; however, this goal is not as easily realized. Donabedian’s (1987) theory requires that identified outcomes be clearly linked with the process that caused the outcome. Researchers need to define the process and justify the causal links with the selected outcomes. The identification of desirable outcomes of care requires dialogue between the recipients and providers of care. Although the providers of care may delineate what is achievable, the recipients of care must clarify what is desirable. A desirable outcome would address issues of specific concern to patients, such as long-term symptoms or ability to conduct activities of daily living. The outcomes must also be relevant to the goals of the health professionals, healthcare system of which the professionals are a part, and society.

There is as yet little scientific basis for judging the precise relationship between each of these complicating factors and the selected outcome. Many of the influencing factors may be outside the jurisdiction or influence of the healthcare system or of the providers within it. One way to address this problem of identifying relevant outcomes is to define a set of proximal outcomes specific to the condition for which care is being provided. A proximal outcome is an outcome that is close to the delivery of care. An example of a proximal outcome is signs and symptoms of disease (Brenner, Curbow, & Legro, 1995). A distal outcome is removed from proximity to the care or a service received and is more influenced by external (nontreatment) factors than a proximal outcome. Quality of life is an example of a distal outcome.

• What are the end results of patients’ care (all care provided by all care providers)?

• What effect does nursing care (all care by all nurses) have on the end results of a patient’s care?

• Are there some nursing acts that have no effects at all on outcomes or that actually cause harm?

• Can we measure and thus identify the end results of nursing care?

• How do we distinguish care provided by nurses from care provided by other professionals in examining patient outcomes?

• When do we measure the effects of care, the end results (e.g., change in symptoms, functioning, or quality of life)—immediately after the care, when the patient is discharged, or much later?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree