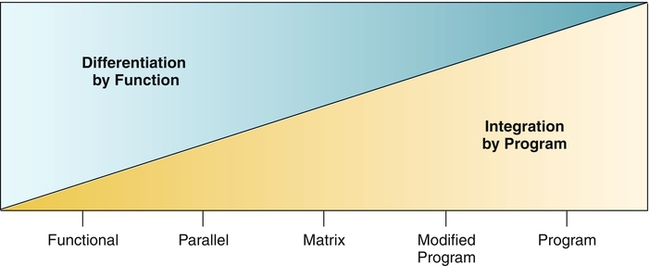

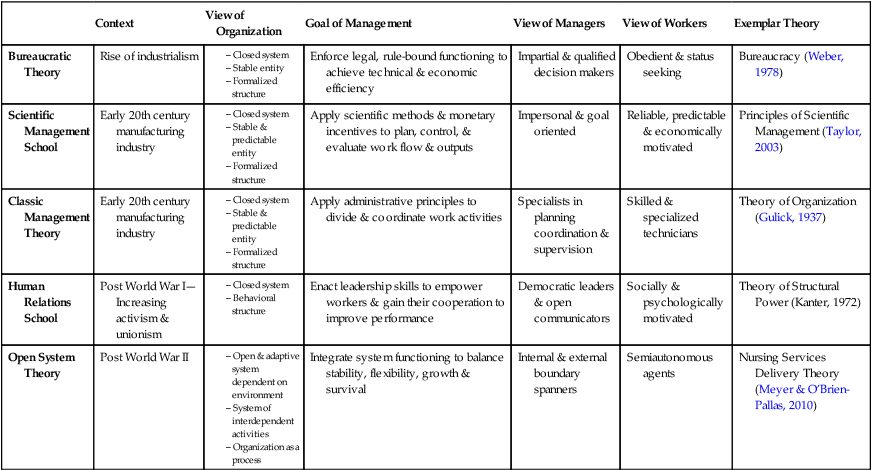

There are many ways to understand organizations, and each understanding reflects different assumptions and tensions regarding the nature and dynamics of organizations. The history of organization theory has been shaped by multiple disciplines, including management, engineering, psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Although this has created a rich and varied understanding of organizations, the field of organization theory contains a variety of approaches to and assumptions about the phenomenon of “organization.” Objectivism, subjectivism, and postmodernism reflect three broad perspectives regarding the nature of reality and the nature of knowledge with respect to the concept of “organization” (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). These perspectives are reviewed briefly with attention to the meanings of social structure, management, and power. When approached as an objective entity, an organization exists as an external reality, independent of its social actors. Organizations are viewed as logical and predictable objects with identifiable and scientifically measurable characteristics (e.g., size) that can be predicted, observed, or manipulated (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). The purpose is to uncover laws that enhance the generalizability of knowledge. Organizational structure is a consequence of the division of and the coordination of labor, which results in a formal set of interrelated and interdependent roles and work groups. Management determines the formal relationships and standardizes the behaviors of individuals and groups in order to align organizational functioning with internal demands (e.g., technology) and external demands (e.g., market conditions, regulatory standards) (Reed, 1992). Typically, power is conceptualized as a resource to be allocated among roles and groups. Modernist theories related to bureaucracy and systems, as well as the schools of scientific management and human relations, have focused on improvements to efficiency, motivation, and performance in the achievement of collective goals (Reed, 1992). These theoretical approaches, which focus on the formal aspects of organizations, are examined in detail in this chapter. In contrast to objectivism, a subjective approach to the phenomenon of organization asserts that an organization cannot exist independent of its social actors. The organization is a social reality that can be known only through human experience, relationships, and shared meanings and symbols (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). Because knowledge is considered to be relative, open to interpretation, and context dependent, the purpose of inquiries is to uncover collective meanings that resonate with the experiences of those involved (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). Social structure therefore arises from and is continuously transformed through social interaction, which is played out against a backdrop of formal rules and material resources directed by management (Reed, 1992). Power is reflected in the struggle between social actors who proactively and self-consciously shape organizational arrangements and secure scarce resources to serve their interests (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006; Reed, 1992). The subjective perspective focuses on the informal aspects of organization and on the freedom of individuals to make choices and to influence organizational life. Symbolic-interpretive theorists are interested in “how the everyday practices of organizational members construct the very patterns of organizing that guide their actions” (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006, p. 126). Examples of daily social practices include routines (e.g., care maps), interactions, and communities of practice. For example, instead of viewing routines as mechanisms to standardize the behavior of individuals (i.e., an objective approach), a subjective approach might examine the changing nature of routines as members selectively modify, adapt, and retain practices in response to varying contexts and conditions (Feldman & Pentland, 2003). In a community of practice, learning occurs through voluntary social interaction whereby clinicians who are committed to a common interest self-organize informally to build ongoing relationships, partake in joint activities, and share resources (Wenger, 2008). An example in nursing would be an informal group of staff nurses who routinely have lunch together and who come to rely on this activity as a source of knowledge related to patient care in terms of problem solving, information exchange, and networking (Wenger, 2008). Departing from the polarization between objectivism and subjectivism, the postmodern view challenges the meanings and interpretations associated with the concept of organization. The basic premise is that the world is known through language. Because language is continually reconstructed and context dependent, knowledge is essentially a power play (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). Notions of order and structure are the subject of scrutiny. Organizations may be thought of as disorderly entities characterized by conflicts and misunderstandings (Reed, 1992). Managerial practices and structures within organizations are seen to legitimize the interests of those in power (Reed, 1992). Even classic organization theorists such as Weber (1978) cautioned that bureaucracies were essentially domination structures that shape the form and purpose of social action through a system of rational rules and norms. Those who control bureaucracies therefore exert significant power over social action. Thus the postmodern organization is understood both as an arena in which power struggles between dominant and subordinate groups play out and as a text to be rewritten to free its members from exploitative and controlling influences (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006; Reed, 1992). Postmodernists challenge the assumption that social structure results from the division and coordination of work among roles and groups. Clegg (1990) suggested that excessive fragmentation of work results in a disjointed and confusing experience for workers who become dependent on more powerful members in the hierarchy to make sense of work flow and goals. To counter this excess control over member actions, he proposed the idea of differentiation whereby people self-manage and coordinate their own activities. Other examples of postmodern approaches to organization include feminist critiques of bureaucracies (e.g., Eisenstein, 1995) and anti-administration theory (Farmer, 1997). Each perspective contributes to stretching the thinking about how organizations are structured and function. In the field of organizational design, the organization is most commonly approached as a social system from the objective perspective. Different theories within this tradition have contributed to understanding organizational social structure (Table 13-1). However, these theories have also been critiqued for rationalizing social action, for favoring efficiency and productivity over other values (e.g., equity, justice), and for adopting an elitist view of management (e.g., O’Connor, 1999). TABLE 13-1 Comparison of Theories of Organization as Social System Compiled by the author. © 2012 Raquel M. Meyer. Used with permission. Although often criticized for its oppressive qualities and administrative burden, the concept of bureaucracy may be better understood when placed within a historical context. Theorist Max Weber (1864-1920) was a German lawyer, professor, and political activist who noted the push of industrialism toward mass production and technical efficiency (Prins, 2000). Weber sought to explain, from a historical perspective, how the bureaucratic structure of large organizations differed from and improved upon other forms of societal functioning (e.g., feudalism). He viewed bureaucracy as a social leveling mechanism founded on impartial and merit-based selection (i.e., legal authority), rather than a social ordering determined by kinship (i.e., traditional authority) or personality (i.e., charismatic authority) (Weber, 1978). However, Weber warned of the potential dehumanizing effects of bureaucracies that emphasized purely economic results (i.e., formal rationality) at the expense of other important social values such as social justice and equality (i.e., substantive rationality) (Weber, 1978). Weber’s descriptions of authority and rationality are foundational concepts in the study of organizations. His interpretation of hierarchy and its relevance to health care organizations are explored later in the chapter. Arising from the experiences and ideas of business leaders and engineers in manufacturing industries, the scientific management school sought to determine the single best way to structure an organization (Donaldson, 1996). A well-known theorist in this field is Frederick W. Taylor (1856-1915), an engineer who authored The Principles of Scientific Management in 1914 (Prins, 2000). Along with colleagues, Taylor’s vision was to improve labor relations and the low industrial standards that plagued the American manufacturing industry by the application of technical solutions (e.g., time and motion studies) (Prins, 2000). He proposed that “THE principal object of management should be to secure the maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with the maximum prosperity for each employé…for each employé (this) means not only higher wages than are usually received by men of his class, but, of more importance still, it also means the development of each man to…the highest grade of work for which his natural abilities fit him” (Taylor, 2003, p. 235). The goal was to enhance organizational performance in a milieu of improved cooperation between management and labor by matching the work performed with the worker’s skills and with economic incentives. However, the experiments and engineering techniques associated with this approach were ultimately criticized for reducing the worker to a mere input in the production process (Prins, 2000). The application of scientific principles to improve the task performance and productivity of workers reflected a bottom-up approach to organizational design (Scott, 1992). In nursing, efforts to redesign nursing jobs or to measure nursing workload often rely on this tradition. Theorists in the human relations school emphasized the informal, rather than formal, aspects of organization social structure. The disciplines of industrial psychology and industrial relations founded this approach, which now persists as the field of organizational behavior (O’Connor, 1999). The social and psychological needs and relationships of workers and groups were thought to be important to work productivity. Improved cooperation between management and workers was proposed to enhance performance and to reduce industrial strife (O’Connor, 1999). The famous Hawthorne experiments were influential in this school of thought. Initial interpretations of the Hawthorne experiments suggested that psychological factors influenced worker motivation because improved worker productivity was observed when researchers gave special attention to workers, regardless of changes to physical surroundings (Scott, 1992). Concepts such as job enlargement and job rotation were promoted to offset the alienation workers experienced because of excessive formalization and division of work processes (Scott, 1992). Formalization is the extent to which the organization uses explicit rules, procedures, job descriptions, and communications to prescribe roles and role interactions, govern activities, and standardize behaviors (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). Streams of study included leadership behavior, small group dynamics, participative decision making, morale, motivation, and other worker characteristics and behaviors (Scott, 1992). In nursing, this school of thought is reflected in efforts to meet the professional development needs of nurses, to enhance nurse autonomy and empowerment, and to involve nurses in decision-making processes to improve organizational functioning. Open system theory emphasizes the dynamic interaction and interdependence of the organization with its external environment and its internal subsystems. Meyer and colleagues (2010) conceptualized the health care organization as an open system characterized by energy transformation, a dynamic steady state, negative entropy, event cycles, negative feedback, differentiation, integration and coordination, and equifinality. Inputs (i.e., characteristics of care recipients, nurses, resources), throughputs (the delivery of nursing services arising from the nature of the work, structures, and work conditions), and outputs (i.e., clinical, human resource, and organizational outcomes) were theorized to interact dynamically to influence the global work demands placed on nursing work groups at the point of care in production subsystems. Contingency theory is a subset of open system theory positing that there is no single right way to structure an organization. Effective organizational performance depends on the fit between structure and multiple contingency factors such as technology, size, and strategy (Donaldson, 1996). Mark and colleagues (1996) applied contingency theory to the evaluation of nursing care delivery system outcomes. The basic premise was that, to perform effectively and produce quality outcomes, an organization must structure and adapt its nursing units to complement the environment and technology. Technology is a core concept in contingency theory and refers to the work performed. Technology can be examined in terms of task uncertainty (i.e., repetitive nature of the task), diversity (i.e., number of different components), and interdependence (i.e., degree to which work processes are interrelated) (Scott, 1992). Highly repetitive and distinct tasks are amenable to mass production technologies (e.g., manufacturing industry). In contrast, highly uncertain and interdependent tasks require discretion, improvisation, and more intense coordination structures across team-driven networks (Donaldson, 1996; Scott, 1992). The work performed by health care professionals is often considered to be highly uncertain, diverse, interdependent, and reliant on group coordination. For example, in a study of hospital joint replacements, teams with high levels of shared knowledge and goals and mutual respect positively influenced patient-assessed quality of care despite shortened lengths of stay (Gittell, 2004). In this study, task uncertainty was intensified by time constraints (i.e., shorter lengths of stay), task diversity was reflected by the multidisciplinary roles, task interdependence resulted as multidisciplinary work was performed concurrently, and the coordination device was teamwork. Theories of networks are also applied to organizational structure. Social network analysis, which builds on a systems view of organizations, examines and interprets the structures and patterns of the formal and informal relationships among members of the organization (Tichy et al., 1979). In nursing, for instance, social network analysis has been used to explore the social and geographical ties of senior nurse executives and physicians in the United Kingdom in relation to profession, gender, age, rank, location, and frequency of contact (West & Barron, 2005). A formal organization that employs people to achieve predetermined goals divides the work among its members by assigning tasks and delegating responsibilities to positions and work units. Structure is a by-product of the basic need to divide the labor into the specific tasks to be performed and a consequent need to coordinate these tasks to accomplish the activity or goal. The structure of an organization can be defined as the “total of the ways in which its labor is divided into distinct tasks and then its coordination is achieved among these tasks” (Mintzberg, 1983, p. 2). The division (or differentiation) of work by occupation or by function is a form of specialization. Specialization is the extent to which work is divided and assigned to positions and divisions (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006). As occupations and functions multiply in number, an organization increases in complexity and size (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Size is a quantitative measure of personnel, physical capacity, volume of inputs or outputs, or discretionary resources of an organization (Kimberly, 1976). The advantages of specialization include improved work performance and a critical mass of experts (Charnes & Tewksbury, 1993). In health care, specialist roles have emerged to address the increasing complexities of care and technology. For example, occupations such as social work, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and respiratory therapy represent specialized areas of knowledge that subdivide care with the aim of improving efficiency and outcomes. Within nursing, specialist roles have also evolved to address specific facets of practice. Advanced practice roles such as clinical nurse educators, nurse practitioners, and nurse anesthetists represent specialized areas of nursing knowledge. Organizations may also differentiate work units by function to serve distinct client populations. For instance, rather than a single, general intensive care unit, an organization may establish several intensive care units by medical specialty (e.g., cardiovascular, neurosurgical, neonatal) or grouped into a “service line.” At the work group level, nursing care delivery models (e.g., team, primary, or total nursing care models) reflect different ways of dividing and coordinating the work among a team of nurses caring for clients. Subdividing work creates breaks in work flow. Organizations address this challenge by integrating work processes across roles and subunits using coordination devices (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Coordination (or integration) involves bringing together and connecting the smaller elements of an organization to achieve a set of collective tasks (Van de Ven et al., 1976). Coordination is especially necessary when resources must be shared or the work performed by different work groups or roles is interdependent (Charnes & Tewksbury, 1993). Although coordination mechanisms can improve efficiency, performance, and conflict resolution, their misuse can also result in information overload and communication breakdowns (Van de Ven et al., 1976). At the work group level, coordination involves programming and feedback devices (March & Simon, 1958). In health care, common programming devices used to control work processes are the following: • Standardization of worker skills coordinates work indirectly by specifying the kind of training or education required to perform the work. In nursing, the standardization of worker skills occurs for advanced practice nurses when a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree is required or certification is mandated. • Standardization of work processes coordinates work by pre-specifying or programming content before the work is undertaken. In nursing, standardization of work processes occurs when nurses use routines such as clinical protocols or evidence-based best practice guidelines. • Hierarchical referral may occur when exceptions or unanticipated events arise (Galbraith, 1974). In nursing, hierarchical referral happens when a nurse coordinates the resolution of an exceptional or non-routine clinical situation with a nurse specialist or physician. • Standardization of work outputs coordinates work, before the work is undertaken, through the specification of the results, product, or performance desired or expected. In nursing, work outputs are standardized when care is specified as outcomes objectives or care is managed for outcomes achievement. • Standardization of communication methods coordinates work by providing a uniform infrastructure of information to facilitate exchange among those involved in common work processes (Venkatraman, 1994). In nursing, standardization of information is achieved through electronic health records and relational databases with alerts which allow nurses and other care providers direct and simultaneous access to client information in a consistent format (Gittell & Weiss, 2004). In addition, feedback mechanisms entail the transfer of information in an adaptive and reciprocal manner to foster the exchange of information (Gittell, 2002): • Mutual adjustment coordinates work by using simple informal communication. In nursing, mutual adjustment occurs when one nurse consults another nurse about practice issues, such as how to interpret a policy; or when nurses, physicians, and allied health professionals participate in clinical rounds. • Direct supervision coordinates work through the use of a supervisor taking responsibility for the instruction and monitoring of the work of others. In nursing, direct supervision takes place when a nurse supervises the work of assistive personnel. • Boundary spanning roles coordinate work by managing relationships as well as the bidirectional flow of information and materials across functional divisions (Gittell, 2003). In nursing, case managers exemplify a boundary spanning role because these roles manage relationships, exchange information, and negotiate resources with internal and external parties to facilitate care across occupations, services, sectors, funding agencies, and locations. The types of coordination that are used depend on the degree of stability and predictability of the work situation (March & Simon, 1958) and the size of the work unit (Van de Ven et al., 1976). For example, acute health care settings are typically characterized as highly uncertain and interdependent work situations. Patient health needs, acuity, and care trajectories are often highly variable and unpredictable. To ensure comprehensive care, nurses coordinate patient care activities with the work of others in a reciprocal manner because the work performed is highly interdependent. Traditionally, programming devices are thought to be effective under stable and predictable conditions (March & Simon, 1958) and with larger work units (Van de Ven et al., 1976). However, as conditions become increasingly uncertain and variable, as in health care, coordination by feedback is more likely to be used (March & Simon, 1958). Improved health care team performance has been associated with both programming and feedback devices because standardized routines and care paths may enhance, rather than replace, the interactions among health care providers, particularly in situations of increasing uncertainty (Gittell, 2002). At the organizational level, the coordination and division of labor influences size and the degree of organizational centralization and formalization. As organizations grow in size, work units are increasingly subdivided to ensure tasks are accomplished; however, this process slows as organizations become very large, because the gains achieved by subdividing work occur at the expense of the coordination mechanisms necessary to unify system functioning across subunits (Blau, 1970). The need to balance the division of labor with the coordination of subunits and roles eventually constrains organizational size (Blau, 1970). At the organizational level, coordination is often measured by the degree of centralization and formalization. Health care organizations tend to be decentralized and less formalized because professionals are employed to manage highly uncertain work (Scott, 1992). However, as organizations grow and as the work becomes increasingly complex, specialized, and interdependent, there is a pull toward greater centralization and formalization (Scott, 1992). The division and coordination of labor lead to varied organizational forms. As illustrated by the sloping triangles in Figure 13-1, organizational forms reflect a trade-off between differentiation by function and integration by program. Differentiation by function refers to the division of work by occupation. Integration by program means the coordination of work around the delivery of particular products or services. Five basic organizational forms can be situated along a differentiation-integration continuum (Charnes & Tewksbury, 1993). Functional and program forms represent extreme examples of differentiation and integration. The matrix form represents the most balanced form. In reality, organizations are not usually found in these pure forms but rather reflect hybrids of the forms described next.

Organizational Structure

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

ORGANIZATION THEORY

Objective Perspective

Subjective Perspective

Postmodern Perspective

KEY THEORIES OF ORGANIZATIONS AS SOCIAL SYSTEMS

Context

View of Organization

Goal of Management

View of Managers

View of Workers

Exemplar Theory

Bureaucratic Theory

Rise of industrialism

Enforce legal, rule-bound functioning to achieve technical & economic efficiency

Impartial & qualified decision makers

Obedient & status seeking

Bureaucracy (Weber, 1978)

Scientific Management School

Early 20th century manufacturing industry

Apply scientific methods & monetary incentives to plan, control, & evaluate work flow & outputs

Impersonal & goal oriented

Reliable, predictable & economically motivated

Principles of Scientific Management (Taylor, 2003)

Classic Management Theory

Early 20th century manufacturing industry

Apply administrative principles to divide & coordinate work activities

Specialists in planning coordination & supervision

Skilled & specialized technicians

Theory of Organization (Gulick, 1937)

Human Relations School

Post World War I—Increasing activism & unionism

Enact leadership skills to empower workers & gain their cooperation to improve performance

Democratic leaders & open communicators

Socially & psychologically motivated

Theory of Structural Power (Kanter, 1972)

Open System Theory

Post World War II

Integrate system functioning to balance stability, flexibility, growth & survival

Internal & external boundary spanners

Semiautonomous agents

Nursing Services Delivery Theory (Meyer & O’Brien-Pallas, 2010)

Bureaucratic Theory

Scientific Management School

Human Relations School

Open System Theory

KEY ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN CONCEPTS

Division and Coordination of Labor

Organizational Forms

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Organizational Structure

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access