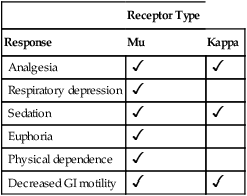

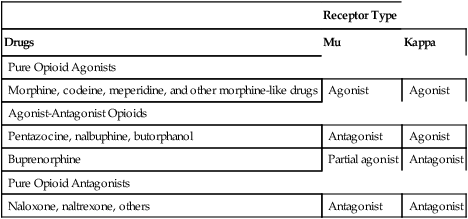

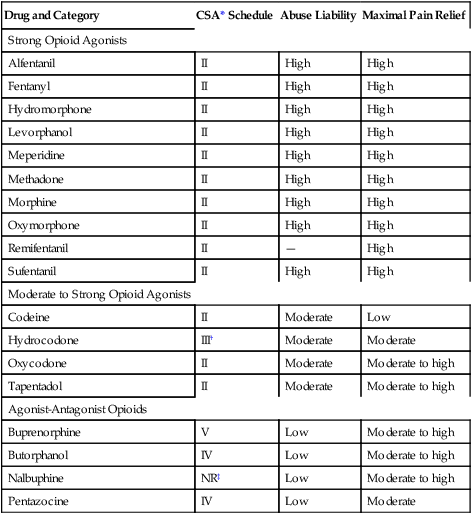

CHAPTER 28 There are three main classes of opioid receptors, designated mu, kappa, and delta. From a pharmacologic perspective, mu receptors are the most important. Why? Because opioid analgesics act primarily by activating mu receptors, although they also produce weak activation of kappa receptors. As a rule, opioid analgesics do not interact with delta receptors. In contrast to opioid analgesics, endogenous opioid peptides act through all three opioid receptors, including delta receptors. Important responses to activation of mu and kappa receptors are summarized in Table 28–1. TABLE 28–1 Important Responses to Activation of Mu and Kappa Receptors Drugs that act at opioid receptors are classified on the basis of how they affect receptor function. At each type of receptor, a drug can act in one of three ways: as an agonist, partial agonist, or antagonist. (Recall from Chapter 5 that a partial agonist is a drug that produces low to moderate receptor activation when administered alone, but will block the actions of a full agonist if the two are given together.) Based on these actions, drugs that bind opioid receptors fall into three major groups: (1) pure opioid agonists, (2) agonist-antagonist opioids, and (3) pure opioid antagonists. The actions of drugs in these groups at mu and kappa receptors are summarized in Table 28–2. TABLE 28–2 Drug Actions at Mu and Kappa Receptors The pure opioid agonists activate mu receptors and kappa receptors. By doing so, the pure agonists can produce analgesia, euphoria, sedation, respiratory depression, physical dependence, constipation, and other effects. As indicated in Table 28–3, the pure agonists can be subdivided into two groups: strong opioid agonists and moderate to strong opioid agonists. Morphine is the prototype of the strong agonists. Codeine is the prototype of the moderate to strong agonists. TABLE 28–3 Opioid Analgesics: Abuse Liability and Maximal Pain Relief *CSA = Controlled Substances Act. †In the United States, hydrocodone is available only in combination with aspirin or acetaminophen. These combination products are classified under Schedule III. Four agonist-antagonist opioids are available: pentazocine, nalbuphine, butorphanol, and buprenorphine. The actions of these drugs at mu and kappa receptors are summarized in Table 28–2. When administered alone, the agonist-antagonist opioids produce analgesia. However, if given to a patient who is taking a pure opioid agonist, these drugs can antagonize analgesia caused by the pure agonist. Pentazocine [Talwin] is the prototype of the agonist-antagonists. The use of morphine and other opioids to relieve pain is discussed further in this Chapter (under Clinical Use of Opioids) and in Chapter 29 (Pain Management in Patients with Cancer). • Opioid peptides and morphine-like drugs both produce analgesia when administered to experimental subjects. • Opioid peptides and morphine-like drugs share structural similarities (Fig. 28–1). • Opioid peptides and morphine-like drugs bind to the same receptors in the CNS. • The receptors to which opioid peptides and morphine-like drugs bind are located in regions of the brain and spinal cord associated with perception of pain. • Subjects rendered tolerant to analgesia from morphine-like drugs show cross-tolerance to analgesia from opioid peptides. • The analgesic effects of opioid peptides and morphine-like drugs can both be blocked by the same antagonist: naloxone. Because of their effects on the intestine, opioids are highly effective for treating diarrhea. In fact, antidiarrheal use of these drugs preceded analgesic use by centuries. The impact of opioids on intestinal function is an interesting example of how an effect can be detrimental (constipation) or beneficial (relief of diarrhea) depending on who is taking the medication. Opioids employed specifically to treat diarrhea are discussed in Chapter 80. For individuals who are highly dependent, the abstinence syndrome can be extremely unpleasant. Initial reactions include yawning, rhinorrhea, and sweating. Onset occurs about 10 hours after the final dose. These early responses are followed by anorexia, irritability, tremor, and “gooseflesh”—hence the term cold turkey. At its peak, the syndrome manifests as violent sneezing, weakness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, bone and muscle pain, muscle spasm, and kicking movements—hence, “kicking the habit.” Giving an opioid at any time during withdrawal rapidly reverses all signs and symptoms. Left untreated, the morphine withdrawal syndrome runs its course in 7 to 10 days. It should be emphasized that, although withdrawal from opioids is unpleasant, the syndrome is rarely dangerous. In contrast, withdrawal from general CNS depressants (eg, barbiturates, alcohol) can be lethal (see Chapter 34). The abuse liability of the opioids is reflected in their classification under the Controlled Substances Act. (The provisions of this act are discussed in Chapter 37.) As shown in Table 28–3, morphine and all other strong opioid agonists are classified under Schedule II. This classification reflects a moderate to high abuse liability. The agonist-antagonist opioids have a lower abuse liability and hence are classified under Schedule IV (butorphanol, pentazocine) or Schedule V (buprenorphine), or have no classification at all (nalbuphine). Healthcare personnel who prescribe, dispense, and administer opioids must adhere to the procedures set forth in the Controlled Substances Act. The major interactions between morphine and other drugs are summarized in Table 28–4. Some interactions are adverse, and some are beneficial. TABLE 28–4 Interactions of Morphine-Like Drugs with Other Drugs In an effort to produce a strong analgesic with a low potential for respiratory depression and abuse, pharmaceutical scientists have created many new opioid analgesics. However, none of the newer pure opioid agonists can be considered truly superior to morphine: These drugs are essentially equal to morphine with respect to analgesic action, abuse liability, and the ability to cause respiratory depression. Also, to varying degrees, they all cause sedation, euphoria, constipation, urinary retention, cough suppression, hypotension, and miosis. However, despite their similarities to morphine, the newer drugs do have unique qualities. Hence one agent may be more desirable than another in a particular clinical setting. With all of the newer pure opioid agonists, toxicity can be reversed with an opioid antagonist (eg, naloxone). Important differences between morphine and the newer strong opioid analgesics are discussed below. Table 28–5 summarizes dosages, routes, and time courses for morphine and the newer agents. TABLE 28–5 Clinical Pharmacology of Pure Opioid Agonists

Opioid (narcotic) analgesics, opioid antagonists, and nonopioid centrally acting analgesics

Opioid analgesics

Introduction to the opioids

Terminology

Opioid receptors

Receptor Type

Response

Mu

Kappa

Analgesia

Respiratory depression

Sedation

Euphoria

Physical dependence

Decreased GI motility

Classification of drugs that act at opioid receptors

Receptor Type

Drugs

Mu

Kappa

Pure Opioid Agonists

Morphine, codeine, meperidine, and other morphine-like drugs

Agonist

Agonist

Agonist-Antagonist Opioids

Pentazocine, nalbuphine, butorphanol

Antagonist

Agonist

Buprenorphine

Partial agonist

Antagonist

Pure Opioid Antagonists

Naloxone, naltrexone, others

Antagonist

Antagonist

Pure opioid agonists.

Drug and Category

CSA* Schedule

Abuse Liability

Maximal Pain Relief

Strong Opioid Agonists

Alfentanil

II

High

High

Fentanyl

II

High

High

Hydromorphone

II

High

High

Levorphanol

II

High

High

Meperidine

II

High

High

Methadone

II

High

High

Morphine

II

High

High

Oxymorphone

II

High

High

Remifentanil

II

—

High

Sufentanil

II

High

High

Moderate to Strong Opioid Agonists

Codeine

II

Moderate

Low

Hydrocodone

III†

Moderate

Moderate

Oxycodone

II

Moderate

Moderate to high

Tapentadol

II

Moderate

Moderate to high

Agonist-Antagonist Opioids

Buprenorphine

V

Low

Moderate to high

Butorphanol

IV

Low

Moderate to high

Nalbuphine

NR‡

Low

Moderate to high

Pentazocine

IV

Low

Moderate

Agonist-antagonist opioids.

Basic pharmacology of the opioids

Morphine

Therapeutic use: relief of pain

Mechanism of analgesic action.

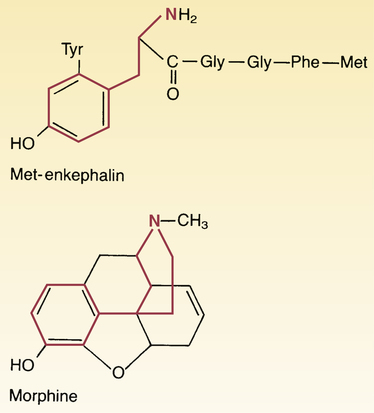

Structural similarity between morphine and met-enkephalin.

Structural similarity between morphine and met-enkephalin.

In the morphine structural formula, highlighting indicates the part of the molecule thought responsible for interaction with opioid receptors. In the met-enkephalin structural formula, highlighting indicates the region of structural similarity with morphine.

Adverse effects

Constipation.

Tolerance and physical dependence

Physical dependence.

Abuse liability

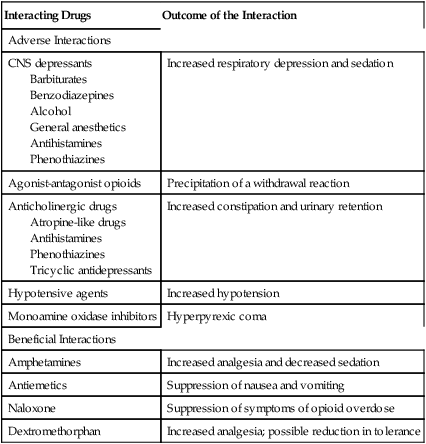

Drug interactions

Interacting Drugs

Outcome of the Interaction

Adverse Interactions

CNS depressants

Barbiturates

Benzodiazepines

Alcohol

General anesthetics

Antihistamines

Phenothiazines

Increased respiratory depression and sedation

Agonist-antagonist opioids

Precipitation of a withdrawal reaction

Anticholinergic drugs

Atropine-like drugs

Antihistamines

Phenothiazines

Tricyclic antidepressants

Increased constipation and urinary retention

Hypotensive agents

Increased hypotension

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Hyperpyrexic coma

Beneficial Interactions

Amphetamines

Increased analgesia and decreased sedation

Antiemetics

Suppression of nausea and vomiting

Naloxone

Suppression of symptoms of opioid overdose

Dextromethorphan

Increased analgesia; possible reduction in tolerance

Other strong opioid agonists

Time Course of Analgesic Effects

Drug and Route*

Equianalgesic Dose (mg)†

Onset (min)

Peak (min)

Duration (hr)

Codeine

PO

200

30–45

60–120

4–6

IM

130

10–30

30–60

4–6

SubQ

130

10–30

30–60

4–6

Fentanyl

IM

0.1

7–8

—

1–2

IV

0.1

—

—

0.5–1

Transdermal‡

—

Delayed

24–72

72

Transmucosal§

—

10–15

20

1–2

Nasal spray

—

10–15

15–20

1–2

Hydrocodone

PO

30

10–30

30–60

4–6

Hydromorphone

PO (IR)

7.5

30

90–120

4

PO (ER)

7.5

—

360–480

18–24

IM

1.5

15

30–60

4–5

IV

1.5

10–15

15–30

2–3

subQ

1.5

15

30–90

4

Levorphanol

PO

4

10–60

90–120

6–8

IM

2

—

60

6–8

IV

2

—

Within 20

6–8

subQ

2

—

60–90

6–8

Meperidine

PO

300

15

60–90

2–4

IM

75

10–15

30–50

2–4

IV

75

1

5–7

2–4

subQ

75

10–15

30–50

2–4

Methadone

PO

20

30–60

90–120

4–6¶

IM

10

10–20

60–120

4–5¶

IV

10

—

15–30

3–4¶

Morphine

PO (IR)

30

—

60–120

4–5

PO (ER)

30

—

420

8–12

IM

10

10–30

30–60

4–5

IV

10

—

20

4–5

subQ

10

10–30

50–90

4–5

Epidural

—

15–60

—

Up to 24

Intrathecal

—

15–60

—

Up to 24

Oxycodone

PO (IR)

20

15–30

60

3–4

PO (CR)

20

—

120–180

Up to 12

Oxymorphone

PO (IR)

10

—

—

4–6

PO (ER)

10

—

—

Up to 12

IM

1

10–15

30–90

3–6

IV

1

5–10

15–30

3–4

subQ

1

10–20

—

3–6

Rectal

10

15–30

120

3–6

Tapentadol

PO

100

45–60

90–120

4–8 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Opioid (narcotic) analgesics, opioid antagonists, and nonopioid centrally acting analgesics

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access