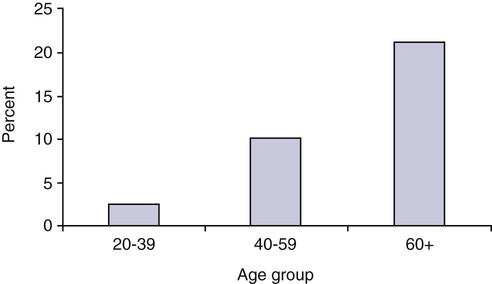

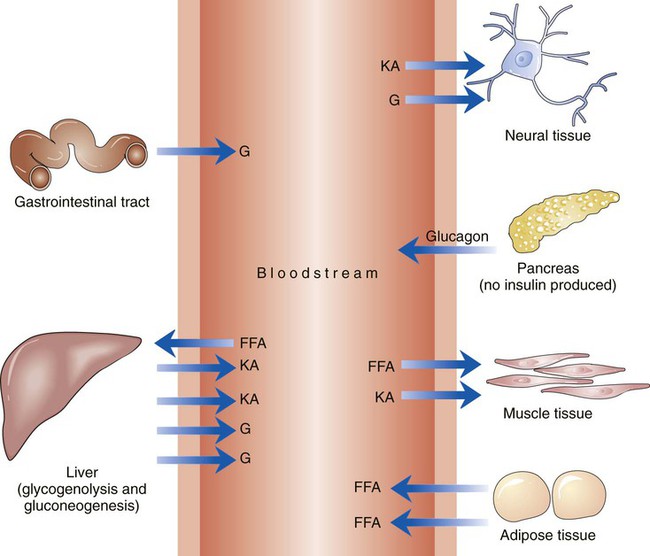

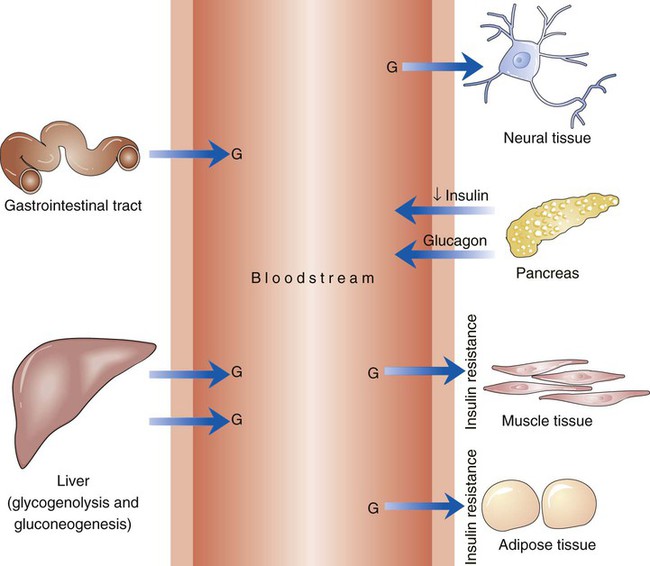

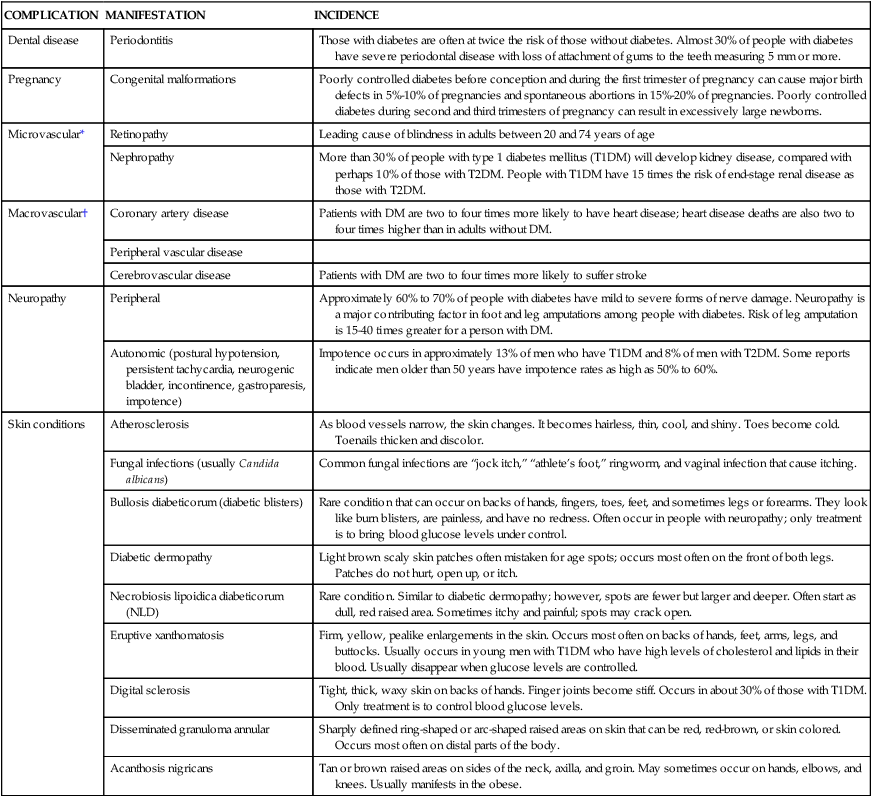

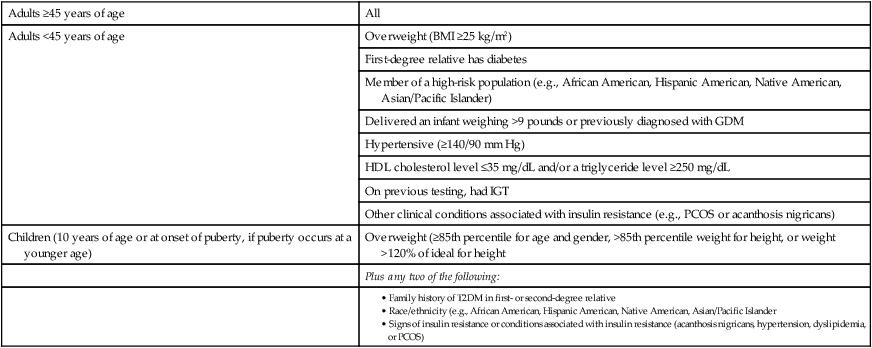

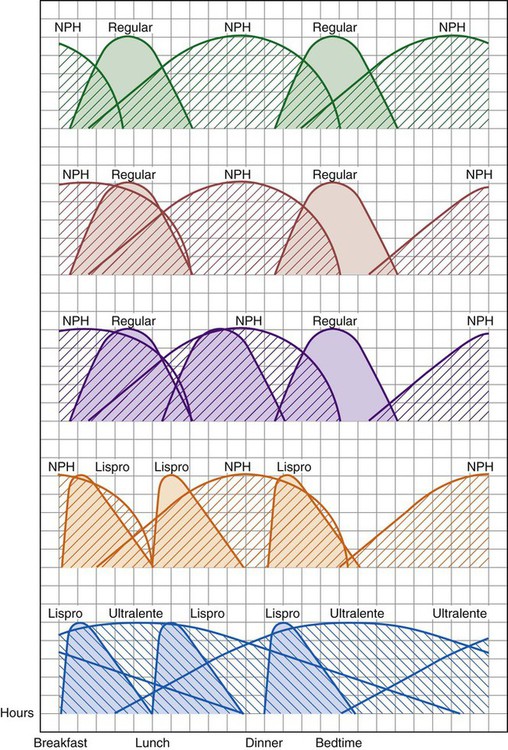

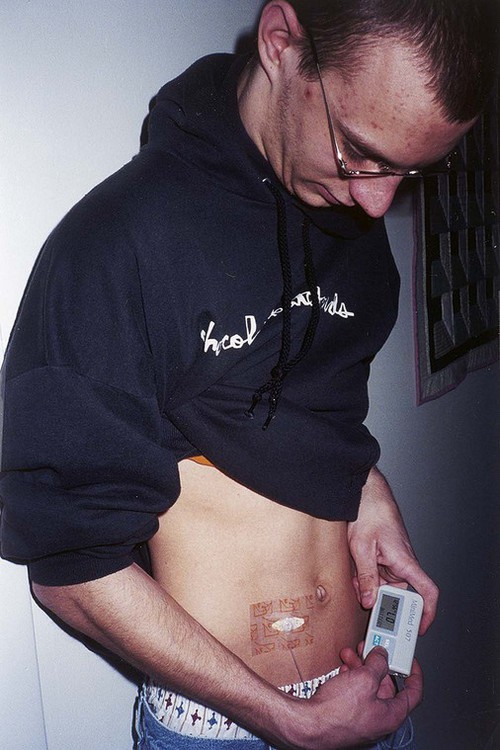

The number of people diagnosed with diabetes is at epidemic proportions in the United States1 (Figure 19-1), and it is estimated that more than 6.2 million people with the disease have not been diagnosed (Box 19-1).2 As a chronic disorder, diabetes mellitus requires long-term lifestyle changes of both dietary intake and physical activity. Approaching this disorder in a proactive manner by maintaining blood glucose levels as near to normal as possible can lessen the negative impact of diabetes and achieve a higher level of wellness (see the Personal Perspectives box, A Tale of Diabetes). Diabetes mellitus is a group of conditions characterized by either a relative or complete lack of insulin secretion by the beta cells of the pancreas or by defects of cell insulin receptors, which results in disturbances of carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism and hyperglycemia (Figure 19-2).3 Diabetes is usually diagnosed and characterized by elevated fasting blood glucose (>126 mg/dL if found on at least two occasions) or hyperglycemia. The main goal of treatment is maintenance of insulin/glucose homeostasis. In addition to everyday maintenance necessary to control blood glucose levels, diabetes mellitus is associated with disability and premature death because of the disease’s effect on structural and functional alterations in many body systems, especially macrovascular and microvascular damage. Ranked as one of the most costly health problems in America,4 diabetes mellitus is often called a “silent killer.” Everyone with diabetes mellitus is vulnerable to long-term complications (Table 19-1) and premature death, which is associated with all types of diabetes. Manifestation of these complications may be preempted with control of hyperglycemia2,5–7 (Table 19-2). Macrovascular complications increase the risk of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular accidents. Microvascular effects include nephropathy (kidney disorder) and retinopathy (eye disorder from blood vessel changes). As a result of nephropathy, approximately half of all individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus develop chronic renal failure and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in North America. In addition, neuropathy complications affect peripheral circulation, causing decreased sensations in extremities that may result in injury without the patient’s knowledge. Healing is impaired because of the effects of diabetes on the circulatory system; gangrene may develop, and amputation may be necessary (Figure 19-3). Autonomic effects of diabetes may include orthostatic hypotension, persistent tachycardia, gastroparesis, neurogenic bladder (urinary bladder dysfunction from neurologic damage), impotence, and impaired visceral pain sensation that can obscure symptoms of angina pectoris or myocardial infarction. TABLE 19-1 CLINICAL COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS *Compounds effects of macrovascular problems. †Exacerbated by concurrent hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and aging. Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, Atlanta, 2007, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008. Accessed March 29, 2010, from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf; American Diabetes Association: Skin complications, Alexandria, Va, Author. Accessed March 29, 2010, from www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/complications/skin-complications.html; National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Disease: National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse: Diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT), NIH Pub No. 08-3874, Bethesda, Md, 2008 (May), National Institutes of Health. Accessed March 29, 2010, from http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/control/; National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases: National diabetes statistics, NIH Pub No 08-3892, Bethesda, Md, 2008 (June), National Institutes of Health. Accessed March 29, 2010, from http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/index.htm. TABLE 19-2 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSING DIABETES *Patients with any form of diabetes may require insulin treatment at some stage of their disease. Such use of insulin does not classify the patient as having type 1 DM. †Symptoms include polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. Data from American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus, Diabetes Care, 29(Suppl 1):S43-S48, 2006; American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2006, Diabetes Care 29(Suppl 1):S4-S42, 2006; American Diabetes Association: Youth type 2 diabetes, Diabetes Care 28(3):638-644, 2005; American Diabetes Association: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Diabetes Care 27(Suppl 1):S88-S90, 2004; American Diabetes Association: Type 2 diabetes in the young, Diabetes Care 27(4):998-1010, 2004; Nabhan F, Emanuele MA, Emanuele N: Latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood, Postgrad Med Online 117(3):7-12, 2005. Retrieved March 25, 2006, from www.postgradmed.com/index.php?article=1597; Thomas AM: Pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. In Thomas AM, Gutierrez YM, editors: American Dietetic Association guide to gestational diabetes mellitus, Chicago, 2005, American Dietetic Association. Development of these long-term complications is believed to be correlated to the level and frequency of hyperglycemia experiences throughout the life span of a person who has diabetes. Results of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial8 indicate intensive therapy is more effective than conventional therapy in delaying and slowing progression of retinopathy by 75%, nephropathy by 50%, and neuropathy by 60% in patients with type 1 DM. Results of the United Kingdom’s Prospective Diabetes Study9 indicate better blood glucose control reduces risk of retinopathy by 25% and nephropathy by 30% and possibly reduces neuropathy in type 2 DM. Glucose intolerance can be classified into two primary categories: type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)* and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Other types include latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and other forms of diabetes.3,10,11 These classifications, based on etiology, treatment needs, and their symptoms, are summarized in Table 19-3. More than 90% of people with diabetes have T2DM, whereas 5% to 10% have T1DM.2,3 TABLE 19-3 METABOLIC GOALS IN DIABETES MANAGEMENT *Measurement should be made 1 to 2 hours after the beginning of the meal. Data from American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2010, Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S11-S61, 2010. Onset of T1DM is usually sudden. Cells use glucose for energy, and without endogenous insulin, cells literally begin to starve. The body responds by sending signals to eat because cells are hungry, but because the end product of digestion (glucose) cannot enter cells, glucose builds up in the bloodstream. It is common for the person to experience weight loss while consuming large quantities of food (polyphagia). Because glucose cannot enter cells and it builds up in the bloodstream, blood becomes hypertonic and the body tries to get rid of the excess glucose by increasing urine output (polyuria). In reaction to increased excretion of urine, the body again responds by increasing thirst (polydipsia) to replace lost fluids (Box 19-2). The majority of individuals diagnosed with T1DM are usually 20 years of age or younger, but a growing number of cases are being documented in older individuals.12 T1DM is an autoimmune disease resulting in beta-cell destruction.3,12,13 Causes of the autoimmune destruction of beta cells are not clearly understood, but multiple genetic predispositions and unidentified environmental factors appear to contribute to T1DM.2 One or more autoantibodies are present in 85% to 89% of individuals diagnosed with T1DM.12 Rate of beta-cell destruction is variable, being rapid in infants and children and slow in adults. In fact, the first manifestation of T1DM may be diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Adults may retain enough residual beta-cell function to prevent ketoacidosis for many years, but when they eventually become dependent on insulin, they also are at risk for DKA.3 Some forms of T1DM have no known cause and are referred to as idiopathic diabetes. Individuals with idiopathic diabetes produce no insulin and are prone to ketoacidosis, but they have no evidence of autoimmunity. Individuals with T1DM who fall into this category represent a very small minority, and most are of African or Asian ancestry.3 Everyone with T1DM requires exogenous insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels and to survive.14 Some individuals with T2DM may require insulin to optimize blood glucose control. Regardless of the type of diabetes, the goal of insulin therapy, in conjunction with nutrition therapy and physical activity,15 is to mimic physiologic insulin delivery. Optimal insulin management can be realized only by evaluating blood glucose monitoring records, adjusting food and exercise activities, and proposing insulin adjustments. Bioengineered human insulin is the only insulin available for use in the United States. Types of insulin are classified into three groups according to duration of their action: rapid or short acting, intermediate acting, and long acting (Table 19-4). Patterns of insulin administration vary with type of diabetes and desired glycemic control (Figure 19-4). TABLE 19-4 *Times given are averages of all types of insulin in the category. Data from Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis (www.lilly.com); Novo Nordisk, Denmark (www.novonordisk.com); Aventis Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Sanofi Aventis), Bridgewater, NJ (www.lantus.com); Pfizer Inc., New York (www.pfizer.com); Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., San Diego (www.symlin.com); Rystrom JK: Insulin therapy. In Ross TA, Boucher JL, O’Connell BS, editors: American Dietetic Association guide to diabetes: Medical nutrition therapy and education, Chicago, 2005, American Dietetic Association. As you can see in Figure 19-4, a single dose of insulin is rarely capable of providing optimal glycemic control in T1DM. There are three basic types of insulin administration regimens: fixed (conventional or standard therapy), flexible (intensive insulin therapy), and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). Conventional or standard insulin therapy is composed of a constant dose of intermediate-acting insulin combined with short- or rapid-acting insulin, or a mixed dose of insulin. Insulins may be mixed by the patient or purchased premixed (for example 30 units of 70/30 insulin). Administration of their insulin (Figure 19-5) and food intake must be synchronized to avoid hypoglycemia.15 Nutrition goals are based on overall diabetes management goals: target glycemic goals and nutrition-related behaviors that affect these goals. Flexible or intensive insulin therapy is composed of multiple daily injections (MDIs) of short- or rapid-acting insulin before meals, as well as intermediate insulin once or twice daily. This allows insulin to be adjusted to correspond with food intake, imitating endogenous insulin secretion in a person without diabetes. Insulin doses can also be adjusted to treat hyperglycemia, inconsistent carbohydrate intake, or modification in usual physical activity.15 Results of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial show that intensive insulin therapy (when compared with conventional therapy) postpones onset and slows development of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy in patients with T1DM.4 It is important that the insulin regimen is integrated with the patient’s lifestyle.9 Individuals who use intensive therapy should know their basic insulin doses for both insulins they use. This allows them to fine-tune short- and rapid-acting insulin doses when they deviate from usual meal plans and/or exercise programs. This type of therapy may not be appropriate for everyone. CSII is a form of intensive therapy. Rapid- or short-acting insulin is pumped continuously in micro-amounts through a subcutaneous catheter and is monitored 24 hours a day (Figure 19-6). Boluses or rapid- or short-acting insulins are given before meals. Along with medical nutrition therapy (discussed later in this chapter) and insulin, exercise is the third component used to treat diabetes. Exercise, like insulin, lowers blood glucose levels, assists in maintaining normal lipid levels, and increases circulation. For most individuals, consistent and individualized exercise helps reduce the therapeutic dose of insulin. Patients with T1DM should be instructed not to perform exercise at the time insulin is at its peak. Ideally, they should exercise when blood glucose levels are between 100 and 200 mg/dL or about 30 to 60 minutes after meals. They should avoid exercising when blood glucose is greater than 250 mg/dL and ketones are present in the urine.15 In the case of T1DM, glucose control can be compromised if proper adjustments are not made in food intake or insulin administration. Patients with T2DM who take oral hypoglycemic agents may be at risk of postexercise hypoglycemia.16 General guidelines that may assist in regulating the glycemic response to exercise in people with T1DM are summarized as follows:17 • Metabolic control before exercise: Avoid exercise if fasting glucose levels are greater than or equal to 250 mg/dL and ketosis is present or if glucose levels are greater than 300 mg/dL, regardless of whether ketosis is present. Ingest added carbohydrate if glucose levels are less than 100 mg/dL. • Blood glucose monitoring before and after exercise: Identify when changes in insulin or food intake are necessary. Learn the blood glucose response to different exercise conditions. • Food intake: Consume added carbohydrate as needed to avoid hypoglycemia. Carbohydrate-based foods should be readily available during and after exercise (Box 19-3). Hypoglycemia can occur during exercise that lasts longer than 1 hour and for up to 24 hours after unusually strenuous, prolonged, and/or sporadic exercise. Blood glucose levels should be monitored, and carbohydrates should be increased and/or insulin adjustments should be made. People with T1DM who do not have complications and are in good blood glucose control can perform all levels of exercise, including leisure activities, recreational sports, and competitive sports.17 To do this safely, the patient must possess the ability to collect self-monitored blood glucose data (during exercise) and then use these data to adjust the therapeutic regimen (insulin and medical nutrition therapy).17 Type 2 DM is an insidious disease. People with T2DM rarely have the classic symptoms of diabetes (i.e., polyuria, polyphagia, polydipsia) (Box 19-4). In fact, some of the first symptoms that cause individuals to seek medical attention are the complications (e.g., heart attack, stroke, neuropathic problems) associated with diabetes. It is not uncommon for a person to have T2DM years before diagnosis. Unlike T1DM, the primary metabolic problem in T2DM is insulin resistance or failure of cells to respond to insulin produced by the body. Eventually the pancreas loses its ability to produce insulin.18 Family history and obesity are the two strongest risk factors for T2DM. In fact, obesity by itself produces an insulin-resistant state that causes beta cells to produce excessive amounts of insulin. Because not all obese people develop diabetes, there seems to be a genetic tendency for diabetes that leads to beta-cell exhaustion and hyperglycemia in some obese people.19 Additionally, upper body obesity has been recognized as an even greater risk factor for diabetes than degree of obesity.20 Upper body obesity, defined as a waist-to-hip ratio greater than 0.8 for women and 0.95 to 1 for men, is a risk factor not only for diabetes but also heart disease and hypertension2 (see also the Cultural Considerations box, Factors of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence). Oral glucose-lowering medications are used to treat T2DM when diet and physical activity alone cannot control hyperglycemia. The variety of new drugs for treatment of diabetes has greatly expanded during the past several years. There are seven classes of oral diabetes medications (Table 19-5).21,22 TABLE 19-5

Nutrition for Diabetes Mellitus

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Role in Wellness

Diabetes Mellitus

COMPLICATION

MANIFESTATION

INCIDENCE

Dental disease

Periodontitis

Those with diabetes are often at twice the risk of those without diabetes. Almost 30% of people with diabetes have severe periodontal disease with loss of attachment of gums to the teeth measuring 5 mm or more.

Pregnancy

Congenital malformations

Poorly controlled diabetes before conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy can cause major birth defects in 5%-10% of pregnancies and spontaneous abortions in 15%-20% of pregnancies. Poorly controlled diabetes during second and third trimesters of pregnancy can result in excessively large newborns.

Microvascular*

Retinopathy

Leading cause of blindness in adults between 20 and 74 years of age

Nephropathy

More than 30% of people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) will develop kidney disease, compared with perhaps 10% of those with T2DM. People with T1DM have 15 times the risk of end-stage renal disease as those with T2DM.

Macrovascular†

Coronary artery disease

Patients with DM are two to four times more likely to have heart disease; heart disease deaths are also two to four times higher than in adults without DM.

Peripheral vascular disease

Cerebrovascular disease

Patients with DM are two to four times more likely to suffer stroke

Neuropathy

Peripheral

Approximately 60% to 70% of people with diabetes have mild to severe forms of nerve damage. Neuropathy is a major contributing factor in foot and leg amputations among people with diabetes. Risk of leg amputation is 15-40 times greater for a person with DM.

Autonomic (postural hypotension, persistent tachycardia, neurogenic bladder, incontinence, gastroparesis, impotence)

Impotence occurs in approximately 13% of men who have T1DM and 8% of men with T2DM. Some reports indicate men older than 50 years have impotence rates as high as 50% to 60%.

Skin conditions

Atherosclerosis

As blood vessels narrow, the skin changes. It becomes hairless, thin, cool, and shiny. Toes become cold. Toenails thicken and discolor.

Fungal infections (usually Candida albicans)

Common fungal infections are “jock itch,” “athlete’s foot,” ringworm, and vaginal infection that cause itching.

Bullosis diabeticorum (diabetic blisters)

Rare condition that can occur on backs of hands, fingers, toes, feet, and sometimes legs or forearms. They look like burn blisters, are painless, and have no redness. Often occur in people with neuropathy; only treatment is to bring blood glucose levels under control.

Diabetic dermopathy

Light brown scaly skin patches often mistaken for age spots; occurs most often on the front of both legs. Patches do not hurt, open up, or itch.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD)

Rare condition. Similar to diabetic dermopathy; however, spots are fewer but larger and deeper. Often start as dull, red raised area. Sometimes itchy and painful; spots may crack open.

Eruptive xanthomatosis

Firm, yellow, pealike enlargements in the skin. Occurs most often on backs of hands, feet, arms, legs, and buttocks. Usually occurs in young men with T1DM who have high levels of cholesterol and lipids in their blood. Usually disappear when glucose levels are controlled.

Digital sclerosis

Tight, thick, waxy skin on backs of hands. Finger joints become stiff. Occurs in about 30% of those with T1DM. Only treatment is to control blood glucose levels.

Disseminated granuloma annular

Sharply defined ring-shaped or arc-shaped raised areas on skin that can be red, red-brown, or skin colored. Occurs most often on distal parts of the body.

Acanthosis nigricans

Tan or brown raised areas on sides of the neck, axilla, and groin. May sometimes occur on hands, elbows, and knees. Usually manifests in the obese.

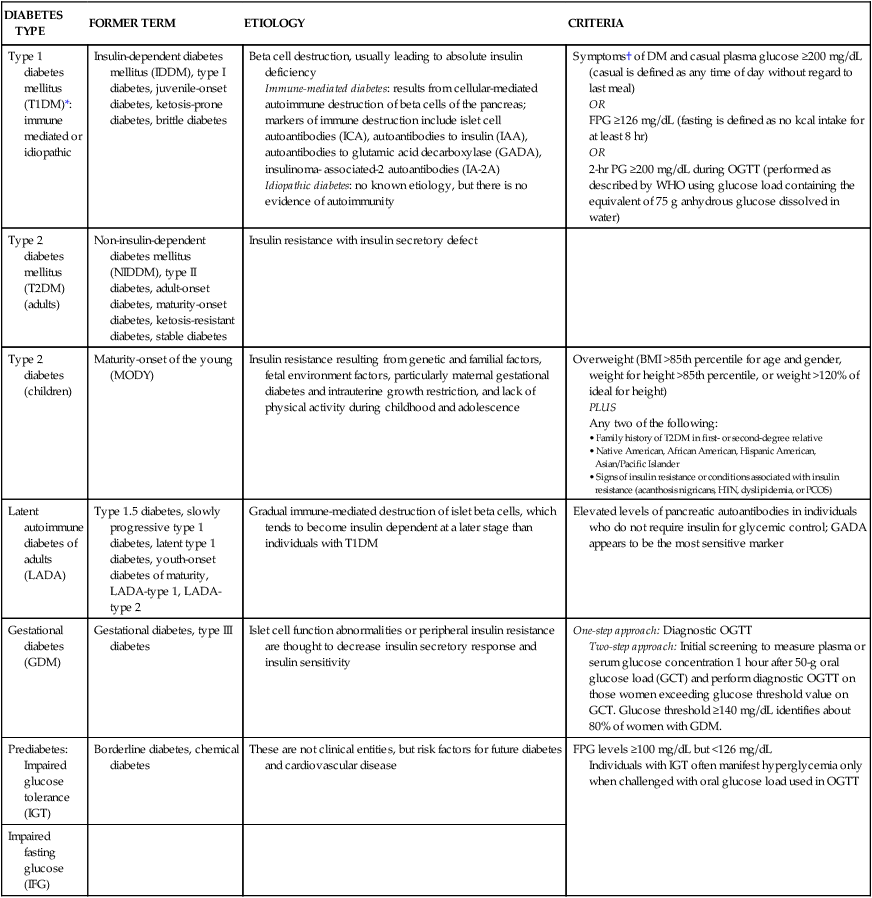

DIABETES TYPE

FORMER TERM

ETIOLOGY

CRITERIA

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)*: immune mediated or idiopathic

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), type I diabetes, juvenile-onset diabetes, ketosis-prone diabetes, brittle diabetes

Beta cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency

Immune-mediated diabetes: results from cellular-mediated autoimmune destruction of beta cells of the pancreas; markers of immune destruction include islet cell autoantibodies (ICA), autoantibodies to insulin (IAA), autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), insulinoma- associated-2 autoantibodies (IA-2A)

Idiopathic diabetes: no known etiology, but there is no evidence of autoimmunity

Symptoms† of DM and casual plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL (casual is defined as any time of day without regard to last meal)

OR

FPG ≥126 mg/dL (fasting is defined as no kcal intake for at least 8 hr)

OR

2-hr PG ≥200 mg/dL during OGTT (performed as described by WHO using glucose load containing the equivalent of 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (adults)

Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), type II diabetes, adult-onset diabetes, maturity-onset diabetes, ketosis-resistant diabetes, stable diabetes

Insulin resistance with insulin secretory defect

Type 2 diabetes (children)

Maturity-onset of the young (MODY)

Insulin resistance resulting from genetic and familial factors, fetal environment factors, particularly maternal gestational diabetes and intrauterine growth restriction, and lack of physical activity during childhood and adolescence

Overweight (BMI >85th percentile for age and gender, weight for height >85th percentile, or weight >120% of ideal for height)

PLUS

Any two of the following:

Latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA)

Type 1.5 diabetes, slowly progressive type 1 diabetes, latent type 1 diabetes, youth-onset diabetes of maturity, LADA-type 1, LADA-type 2

Gradual immune-mediated destruction of islet beta cells, which tends to become insulin dependent at a later stage than individuals with T1DM

Elevated levels of pancreatic autoantibodies in individuals who do not require insulin for glycemic control; GADA appears to be the most sensitive marker

Gestational diabetes (GDM)

Gestational diabetes, type III diabetes

Islet cell function abnormalities or peripheral insulin resistance are thought to decrease insulin secretory response and insulin sensitivity

One-step approach: Diagnostic OGTT

Two-step approach: Initial screening to measure plasma or serum glucose concentration 1 hour after 50-g oral glucose load (GCT) and perform diagnostic OGTT on those women exceeding glucose threshold value on GCT. Glucose threshold ≥140 mg/dL identifies about 80% of women with GDM.

Prediabetes: Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)

Borderline diabetes, chemical diabetes

These are not clinical entities, but risk factors for future diabetes and cardiovascular disease

FPG levels ≥100 mg/dL but <126 mg/dL

Individuals with IGT often manifest hyperglycemia only when challenged with oral glucose load used in OGTT

Impaired fasting

glucose (IFG)

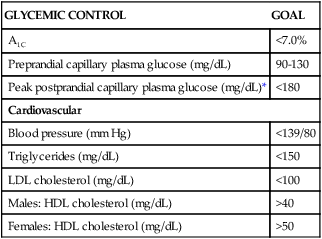

GLYCEMIC CONTROL

GOAL

A1C

<7.0%

Preprandial capillary plasma glucose (mg/dL)

90-130

Peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose (mg/dL)*

<180

Cardiovascular

Blood pressure (mm Hg)

<139/80

Triglycerides (mg/dL)

<150

LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

<100

Males: HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

>40

Females: HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

>50

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Insulin

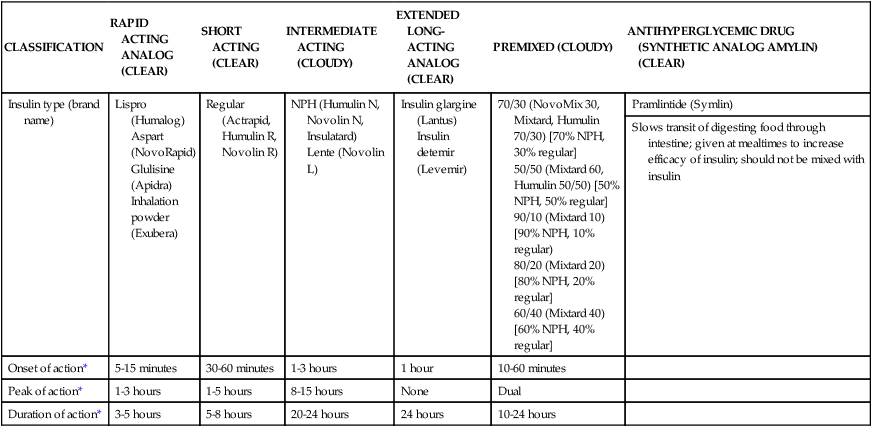

CLASSIFICATION

RAPID ACTING ANALOG (CLEAR)

SHORT ACTING (CLEAR)

INTERMEDIATE ACTING (CLOUDY)

EXTENDED LONG-ACTING ANALOG (CLEAR)

PREMIXED (CLOUDY)

ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC DRUG (SYNTHETIC ANALOG AMYLIN) (CLEAR)

Insulin type (brand name)

Lispro (Humalog)

Aspart (NovoRapid)

Glulisine (Apidra)

Inhalation powder (Exubera)

Regular (Actrapid, Humulin R, Novolin R)

NPH (Humulin N, Novolin N, Insulatard)

Lente (Novolin L)

Insulin glargine (Lantus)

Insulin detemir (Levemir)

70/30 (NovoMix 30, Mixtard, Humulin 70/30) [70% NPH, 30% regular]

50/50 (Mixtard 60, Humulin 50/50) [50% NPH, 50% regular]

90/10 (Mixtard 10) [90% NPH, 10% regular)

80/20 (Mixtard 20) [80% NPH, 20% regular]

60/40 (Mixtard 40) [60% NPH, 40% regular]

Pramlintide (Symlin)

Slows transit of digesting food through intestine; given at mealtimes to increase efficacy of insulin; should not be mixed with insulin

Onset of action*

5-15 minutes

30-60 minutes

1-3 hours

1 hour

10-60 minutes

Peak of action*

1-3 hours

1-5 hours

8-15 hours

None

Dual

Duration of action*

3-5 hours

5-8 hours

20-24 hours

24 hours

10-24 hours

Exercise

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Oral Glucose-Lowering Medications

DRUG CLASS

DRUG NAME(S)

ACTION

TARGET ORGAN(S)

SIDE EFFECTS

HOW TAKEN

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor (AGIs)

Acarbose: Precose

Delays absorption of glucose from GI tract

Small intestine

Excess flatulence, diarrhea (particularly after high-carbohydrate meal), abdominal pain, may interfere with iron absorption

Must be taken with meals 3 times/day

Miglitol: Glyset

Biguanides

Metformin: Glucophage

Decreases hepatic glucose production and intestinal glucose absorption; improves insulin sensitivity

Liver, small intestine, and peripheral tissues

Less likely to gain weight; may lose weight; anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, metallic taste, may reduce absorption of vitamin B12 and folic acid, rarely suitable for adults <80 yr of age

Take with first main meal

Meglitinides (nonsulfonylurea insulin releasers)

Nateglinide: Starlix

Stimulates secretion of insulin

Pancreatic beta cells

Hypoglycemia and weight gain; repaglinide has a lightly increased risk for cardiac events

Take with meals

Repaglinide: Prandin

Sulfonylureas, First Generation

Acetohexamide: Dymelor

Stimulates secretion of insulin

Pancreatic beta-cells

Hypoglycemia and weight gain; tolbutamide may be associated with cardiovascular complications; chlorpropamide can cause hyponatremia; should not be used by women who are pregnant or nursing, or by individuals allergic to sulfa drugs; sulfonylurea interacts with many other drugs (prescription, OTC, and alternative); Diabinese: avoid alcohol

Take before or with meals

Tolazamide: Tolinase

Tolbutamide: Orinase

Chlorpropamide: Diabinese

Second Generation

Glimepiride: Amaryl

Glyburide: DiaBeta, Micronase, Glynase PresTabs

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

Pioglitazone: Actos

Improves insulin sensitivity

Activates genes involved with fat synthesis and carbohydrate metabolism

Possible liver damage, weight gain, mild anemia

Once or twice daily

Rosiglitazone: Avandia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nutrition for Diabetes Mellitus

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

cup dry cereal

cup dry cereal cup cooked cereal

cup cooked cereal cup cooked rice or pasta

cup cooked rice or pasta cup (6 ounces) unsweetened or sugar-free yogurt

cup (6 ounces) unsweetened or sugar-free yogurt cup canned fruit (canned in juice)

cup canned fruit (canned in juice) cup dried fruit

cup dried fruit cup unsweetened fruit juice

cup unsweetened fruit juice cup cooked potatoes, peas, or corn

cup cooked potatoes, peas, or corn cups cooked vegetables

cups cooked vegetables cup) of nonstarchy vegetables are free

cup) of nonstarchy vegetables are free cup or

cup or  ounce snack food (pretzels, chips)

ounce snack food (pretzels, chips) cup regular ice cream

cup regular ice cream