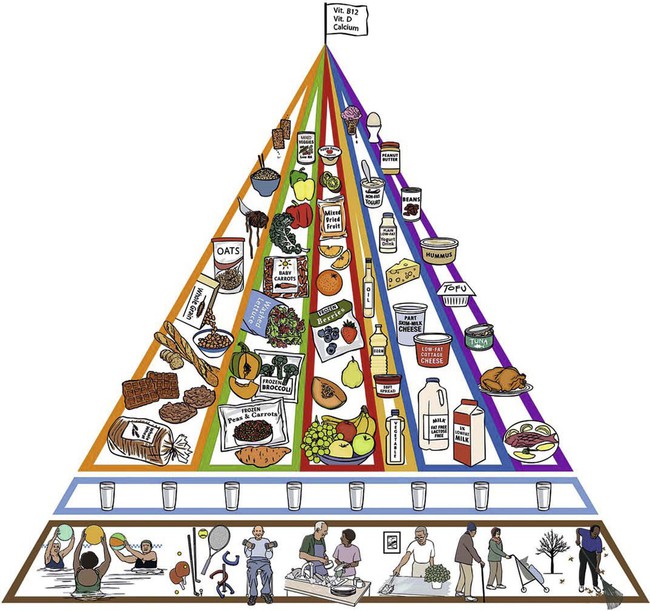

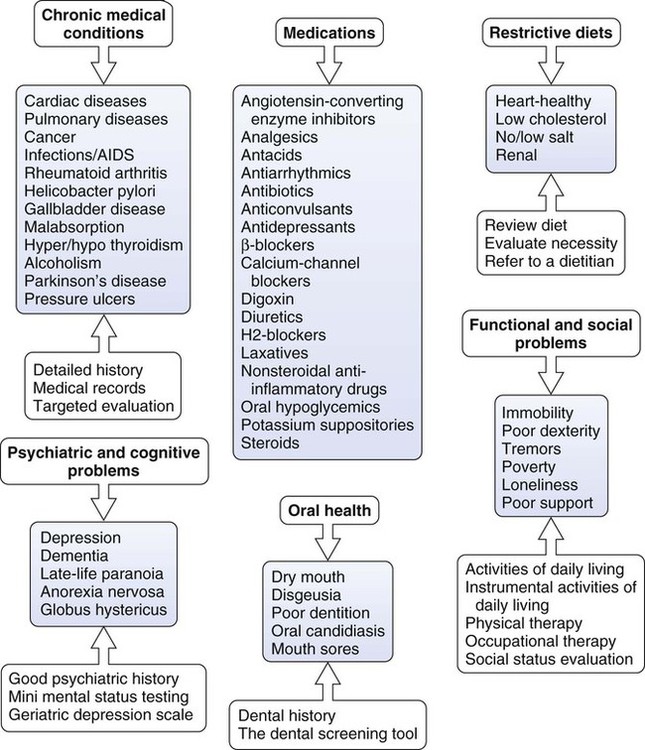

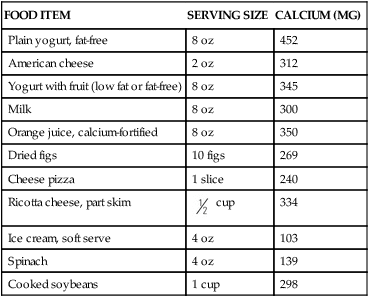

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Discuss nutritional requirements and factors affecting nutrition for older adults. 2. Describe a nutritional screening and assessment. 3. Identify strategies to assist in ensuring adequate nutrition for older adults experiencing hospitalization, institution-alization, and physical and cognitive impairments. 4. Delineate risk factors for poor nutrition and malnutrition, and identify strategies for management. 5. Discuss assessment and interventions for older adults with dysphagia. 6. Discuss interventions that promote good oral hygiene for older people. 7. Develop a plan of care to assist an older person in developing and maintaining good nutritional status. Adequate nutrition is critical to preserving the health of older people. The quality and quantity of diet are important factors in preventing, delaying onset, and managing chronic illnesses associated with aging (American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, Society for Nutrition Education, 2010). Results of studies provide growing evidence that diet can affect longevity and, when combined with lifestyle changes, reduce disease risk. “While diet is only one component in the development and exacerbation of illness (heredity, environment, medical care, social circumstances, and other lifestyle risk factors play a part), eating and drinking habits have been implicated in 6 of the 10 leading causes of death in this country (heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, atherosclerosis, liver disease) as well as in several debilitating disorders such as osteoporosis and diverticulosis” (Haber, 2007). About 87% of older adults have diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or a combination of these diseases that may have dietary implications. (American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, Society for Nutrition Education, 2010). Proper nutrition means that all of the essential nutrients (i.e., carbohydrates, fat, protein, vitamins, minerals, and water) are adequately supplied and used to maintain optimal health and well-being. Although some age-related changes in the gastrointestinal system do occur, these changes are rarely the primary factors in inadequate nutrition. Fulfillment of an older person’s nutritional needs is more often affected by numerous other factors, including chronic disease, life-long eating habits, ethnicity, socialization, income, transportation, housing, food knowledge, functional impairments, health, and dentition. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that only about 17% of older adults consumed a “good” quality diet, with non-Hispanic white persons having the highest scores on the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) and non-Hispanic black persons having the lowest scores (Ervin, 2008). The Modified MyPyramid for Older Adults (over 70 years) has been adapted from the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) MyPyramid. The Modified MyPyramid provides the types and amounts of food that should be eaten to optimize nutrient intake (Figure 14-1). Modifications for older adults include the addition of eight 8-ounce glasses of water to the foundation of the pyramid. Older adults have reduced thirst mechanism and may not consume adequate fluids. Fluid intake is important for older adults to prevent cardiovascular and kidney complications as well as constipation. Additionally, a flag was added at the top to remind older adults that they may not be getting adequate calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12, and may need supplements. With proper instruction, the Modified MyPyramid is an easy and systematic way for a person to evaluate his or her own nutritional intake and independently make corrective adjustments. Pictures can be used to transcend cultural and educational barriers. The USDA also provides ethnic-cultural and vegetarian food pyramids (www.fda.gov). The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan is another highly recommended eating plan for older people that assists older adults with maintenance of optimal weight and management of hypertension. This plan consists of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, poultry, and fish, and restriction of salt intake (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/new_dash.pdf). Similar to other age groups, older adults should limit intake of saturated fat and trans fatty acids. High fat diets cause obesity and increase the risk of heart disease and cancer. Recommendations are that 20% to 35% of total calories should be from fat, 45% to 65% from carbohydrates, and 10% to 35% from proteins. Monounsaturated fats, such as olive oil, are the best type of fat since they lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but leave the high density lipoprotein (HDL) intact or even slightly raise it. A simple technique to determine how much fat a person should consume is to divide the ideal weight in half and allowing that number of grams of fat (Haber, 2007). Presently, the Institute of Medicine’s Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein of 0.8 g/kg per day, based primarily on studies in younger men, may be inadequate for older adults. Results of a recent study (Beasley et al., 2010) suggest that higher protein consumption, as a fraction of total caloric intake, is associated with a decline in risk of frailty in older adults. Protein intake of 1.5 g/kg per day, or 20% to 25% of total calorie intake, may be more appropriate for older adults at risk of becoming frail. Fiber is an important dietary component that some older people do not consume in sufficient quantities. Older adults should increase dietary fiber intake to 14 g per 1000 calories consumed (Ham et al., 2007). Insufficient amounts of fiber in the diet, as well as insufficient fluids, contribute to constipation. Fiber is the indigestible material that gives plants their structure. It is abundant in raw fruits and vegetables and in unrefined grains and cereals. The benefits of fiber include the following: facilitates the absorption of water; helps control weight by delaying gastric emptying and providing a feeling of fullness; improves glucose tolerance by delaying movement of carbohydrate into the small intestine; prevents or reduces constipation by increasing the weight of the stool and shortening the transit time; helps prevent hemorrhoids and diverticulosis by decreasing pressure in the colon, shortening transit time, and increasing stool weight; reduces the risk of heart disease by binding with bile (which contains cholesterol) and causes its excretion; and protects against cancer. Individuals who can chew well could benefit from eating increased amounts of fresh fruits and vegetables daily or combining unsweetened bran with other types of food. It is better to get fiber from food than from fiber supplements such as Metamucil, since they do not contain the essential nutrients found in high-fiber foods and their anticancer benefits are questionable. Ways to increase fiber intake include eating cooked dry beans, peas, and lentils; leaving skins on fruits and vegetables; eating whole fruit rather than drinking fruit juice; and eating whole-grain breads and cereals (National Institute on Aging, 2010). Those who have difficulty chewing could sprinkle oat bran on cereals or in soups, meat loaf, or casseroles. Older people who consume five servings of fruits and vegetables daily will obtain adequate intake of vitamins A, C, and E, and potassium. Americans of all ages eat less than half of the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables (Haber, 2007). After age 50, the stomach produces less gastric acid, which makes vitamin B12 absorption less efficient. Vitamin B12 deficiency in a common and underrecognized condition that is estimated to occur in 12% to 14% of community-dwelling older adults and up to 25% of those residing in institutional settings (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010). Atrophic gastritis and pernicious anemia are the most common causes of vitamin B12 deficiency. Less common causes are a strict vegetarian diet over a long period of time or inadequate absorption after gastrectomy or ileostomy. While intake of this vitamin is generally adequate, older adults should increase their intake of the crystalline form of vitamin B12 from fortified foods such as whole-grain breakfast cereals. Use of proton pump inhibitors for more than one year, as well as histamine H2 receptor blockers can lead to lower serum vitamin B12 levels by impairing absorption of the vitamin from food. Metformin, colchicine, and antibiotic and anticonvulsant agents may also increase the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency (Cadogan, 2010). Calcium and vitamin D are essential for bone health and may prevent osteoporosis and decrease the risk of fracture. Chapter 15 discusses recommendations for calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Calcium is a difficult mineral to absorb, and some foods inhibit calcium absorption (e.g., green beans, peanuts, and summer squash) (Table 14-1). High levels of protein, sodium, or caffeine also cause more calcium to be excreted in the urine and should be avoided. For older adults with inadequate calcium intake from diet, supplemental calcium can be used. TABLE 14-1 CALCIUM CONTENT OF SEVERAL COMMON FOODS Source: National Institutes of Health: Sources of calcium, Washington, D.C. Available at: www.nichd.nih.gov/milk. Accessed November 1, 2008. While most of the research on nutrition and older adults has centered on underweight and frailty, the increase in the prevalence of obesity in the general population, and in older adults, is getting increased attention. More than two-thirds of all adults in the United States are overweight (BMI = 25 to 29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30), and the proportion of older adults who are obese has doubled in the past 30 years (Bales & Buhr, 2008; Flicker et al., 2010; Newman, 2009). “The obesity epidemic is occurring in parallel with the aging of the baby boomer generation. Current estimates in the United States indicate that nearly 70% of those aged 65 and older are overweight or obese and 29% are obese” (Jarosz and Bellar, 2009). Similar trends are observed in other developed and developing countries. Overweight and obesity are growing global public health concerns and are associated with increased health care costs, functional impairments, disability, chronic disease, and nursing home admission (Felix, 2008; Newman, 2009). Socioeconomic deprivation and lower levels of education have been linked to obesity. African Americans have a 51% higher prevalence of obesity compared with whites, and Hispanics have a 21% higher prevalence (CDC, 2010). While there is strong evidence that obesity in younger people lessens life expectancy and has a negative effect on functionality and morbidity, it remains unclear whether overweight and obesity are predictors of mortality in older adults. Concerns have been raised about encouraging apparently overweight older people to lose weight (Bales and Buhr, 2008; Flicker et al., 2010). In what has been termed the obesity paradox, for people who have survived to age 70, mortality risk is lowest in those with a BMI classified as overweight (Felix, 2008, p. 36). Flicker and colleagues (2010) conclude that “BMI thresholds for overweight and obese are overly restrictive for older people. Overweight older people are not at greater mortality risk, and there is little evidence that dieting in this age group confers any benefit; these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that weight loss is harmful” (p. 239). For nursing home residents with severely decreased functional status, obesity may be regarded as a protective factor with regard to functionality and mortality (Kaiser et al., 2010). However, as Jarosz and Bellar (2009) point out, the reduction in muscle mass that occurs with aging (sarcopenia) is increasingly being paired with an increased fat mass in obese older adults (sarcopenic obesity). This may make it more difficult to recognize frailty and/or malnutrition in obese older people. The growing prevalence of obesity in middle and late life could further exacerbate a number of age-related health concerns, depending on body weight gain patterns and the health history of the individual. Felix (2008) also notes the effect on nursing homes expenditures and staff workload in light of the increasing number of obese individuals being admitted for care. At this time, maintaining weight in older persons seems to be a clinical recommendation, and any weight loss interventions in older persons must be “carefully considered on an individualized basis with special attention to the weight history and the medical conditions of each individual” (Bales and Buhr, 2008, p. 311). Maintaining a healthy weight throughout life is one of the most important goals for people of all ages. Malnutrition is defined as a state in which a deficiency, excess or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients causes adverse effects on body form, function, and clinical outcome” (Ahmed and Haboubi, 2010, p. 207). The rising incidence of malnutrition among older adults has been documented in acute care, long-term care, and the community. Between 16% and 30% of older adults are malnourished or at high risk, and about half of this population has protein levels consistent with malnutrition when they are admitted to hospitals (Duffy, 2010). Older adults in skilled nursing facilities and long-term nursing home residents also have a higher incidence of malnutrition. An estimated 15% of community-dwelling older people experience malnutrition, and a recent study links malnutrition in this population to socioeconomic status, functional limitations, and social isolation (Lee & Berthelot, 2010). The diseases and functional impairments that prompt admission to a skilled nursing facility make older people extremely vulnerable to malnutrition. These figures are projected to rise dramatically in the next 30 years (Ahmed & Haboubi, 2010). Malnutrition among older people is clearly a serious challenge for health professionals in all settings. Malnutrition has serious consequences, including infections, pressure ulcers, anemia, hypotension, impaired cognition, hip fractures, and increased mortality and morbidity. “Malnourished older adults take 40% longer to recover from illness, have 2-3 times as many complications, and have hospital stays that are 90% longer” (Haber, 2007, p. 211). Many factors contribute to the occurrence of malnutrition in older adults (Figure 14-2). Kwashiorkor is more acute or subacute but may frequently be superimposed on marasmus. It is precipitated by the stress of an acute illness and develops over weeks. Serum proteins are depleted with consequent edema, and there may be no weight loss. This PEM syndrome has a high mortality rate. Signs and symptoms of PEM are nonspecific, and it is important that other conditions such as malignancy, hyperthyroidism, peptic ulcer, and liver disease are ruled out (Ham et al., 2007). Comprehensive nutritional screening and assessment are essential in identifying older adults at risk for nutrition problems or who are malnourished. Some age-related changes in the senses of taste and smell (chemosenses) and the digestive tract do occur as the individual ages and may affect nutrition. For most older people, these changes do not seriously interfere with eating, digestion, and the enjoyment of food. However, combined with other factors, they may contribute to inadequate nutrition and decreased eating pleasure (Chapter 4). The sense of taste has many components and primarily depends on receptor cells in the taste buds. Taste buds are scattered on the surface of the tongue, the cheek, the soft palate, the upper tip of the esophagus, and other parts of the mouth. Components in food stimulate taste buds during chewing and swallowing, and tongue movements enhance flavor sensation. Fine, subtle taste to discriminate between flavors is an olfactory function, whereas crude taste (e.g. sweet and sour) depends on the taste buds. Individuals have varied levels of taste sensitivity that seem predetermined by genetics and constitution, as well as age variations. Early studies suggested that a decline in the number of taste cells occurs with aging, but more recent studies suggest that “taste cells can regenerate but that the lag time of this turnover may account for the diminished taste response in older adults” (Miller, 2008, p. 363). Age-related changes in the sense of smell and the consequent effect on nutrition is in need of further research. In the past, studies have shown a decline in the sense of smell as the individual ages. Recent research (Markovic et al., 2007) disputes this belief. Results of this study suggested that for perceived odors, olfactory pleasure increases at later stages in the life span, and the perceived intensity of odors remains stable. Decrease in the sense of smell may be related to many factors, including the following: nasal sinus disease, repeated injury to olfactory receptors through viral infections, age-related changes in central nervous system functioning, smoking, medications, and periodontal disease and other dentition problems. Changes in the sense of smell are also associated with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Cacchione, 2008). Age-related changes in the buccal cavity also predispose older people to orodental problems that can significantly affect nutrition (Box 14-1). Aging teeth become worn and darker in color and tend to develop longitudinal cracks. The dentin, or the layer beneath the enamel, becomes brittle and thickens so that pulp space decreases. In addition to years of exposure of the teeth and related structures to microbial assault, the oral cavity shows evidence of wear and tear as a result of normal use (chewing and talking) and destructive oral habits such as bruxism (habitual grinding of the teeth). People who are edentulous and are using complete dentures, continue to have oral health care needs. Ill-fitting dentures affect chewing and hence nutritional intake. People without teeth remain susceptible to oral cancer and other oral diseases. Another common oral problem among older adults is dry mouth (xerostomia). Approximately 25% to 40% of older adults experience xerostomia. More than 500 medications have the side effect of reducing salivary flow. A reduction in saliva and a dry mouth make eating, swallowing, and speaking difficult. It can also lead to significant problems of the teeth and their supporting structure (Jablonski, 2010). Artificial saliva preparations are available (avoid those containing sorbitol), and adequate fluid intake is also important when xerostomia occurs. Chewing on xylitol-flavored fluoride tablets, sugar-free candies, or sugar-free gum with xylitol 15 minutes after meals may stimulate saliva flow and promote oral hygiene (Miller, 2008). Medication review is also indicated to eliminate, if possible, medications contributing to xerostomia. Appetite in persons of all ages is influenced by factors such as physical activity, functional limitations, smell, taste, mood, socialization, and comfort. With age, appetite and food consumption decline. Healthy older people are less hungry and are fuller before meals, consume smaller meals, eat more slowly, have fewer snacks between meals, and become satiated after meals more rapidly than younger people (Ahmed and Haboubi, 2010). Appetite is regulated by a combination of a peripheral satiation system and a central feeding drive. There is some evidence that alterations in the endogenous opioid feeding and drinking drive may decline in aging and contribute to decreased appetite and risk for dehydration. Nearly 20% of old-old individuals have anorexia. Individuals with anorexia are likely to be frailer and more disabled, and are likely to have an increased rate of mortality (Morley, 2010). Decreased stomach fundal compliance, decreased testosterone, and increased leptin and amylin also contribute to decreases in appetite among older people. “Much of the anorexia of aging seems to be related to changes in gastrointestinal activities that occur with aging, with less antral distention, and thus earlier satiety” (Ham et al., 2007, p. 282). Other factors that contribute to decreases in appetite include depression, polypharmacy, oral and dental problems, dementia, and other chronic illnesses, as well as feeding techniques and mealtime ambience in institutions (Morley 2003; Morley, 2010). Lifelong habits of dieting or eating fad foods also echo through the later years. Older people may fall prey to advertisements that claim specific foods maintain youth and vitality or rid one of chronic conditions. Everyone can benefit from improved eating habits, and it’s never too late to change dietary habits to improve health. Following the Modified MyPyramid for Older Adults (Figure 14-1) is best for an ideal diet, with changes based on particular problems, such as hypercholesteremia. Older adults should be counseled to base their dietary decisions on valid research and consultation with their primary care provider. For the healthy older adult, essential nutrients should be obtained from food sources rather than relying on dietary supplements. The fundamentally social aspect of eating has to do with sharing and the feeling of belonging that it provides. All of us use food as a means of giving and receiving love, friendship, or belonging. Often, older adults may be isolated from the mainstream of life because of chronic illness, depression, and other functional limitations. When one eats alone, the outcome is often either overindulgence or disinterest in food. The presence of others during meals is a significant predictor of caloric intake (Locher et al., 2008). Disinterest in food may also result from the effects of medication or disease processes. Misuse and abuse of alcohol are prevalent among older adults and are growing public health concerns. Excessive drinking interferes with nutrition. Drinking alcohol depletes the body of necessary nutrients and often replaces meals, thus making an individual susceptible to malnutrition (Chapter 18). The elderly nutrition program, authorized under Title III of the Older Americans Act (OAA), is the largest national food and nutrition program specifically for older adults. Programs and services include congregate nutrition programs, home-delivered nutrition services (Meals-on-Wheels), and nutrition screening and education. The program is not means-tested, and participants may make voluntary confidential contributions for meals. However, the OAA Nutrition Program reaches less than one-third of older adults in need of its program and services, and those served receive only three meals a week. With the emphasis on community-based care rather than institutional care, expansion of nutrition services should be a priority. These programs enable older adults to avoid or delay costly institutionalization and allow them to stay in their homes and communities. The American Dietetic Association estimates that the cost of one day in a hospital equals the cost of one year of OAA Nutrition Program meals, while the cost of one month in a nursing home equals that of providing midday meals five days a week in the community for about seven years (American Dietetic Association, 2010). The side effects of medications prescribed for these conditions may further impair nutritional status. A number of prevalent disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are associated with nutritional concerns including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), ulcers, constipation, diverticulosis, and colon cancer. Dysphagia, often a result of stroke or dementia, significantly affects nutrition. Diseases affecting function, such as arthritis and Parkinson’s disease, may impair eating ability. Cancers and subsequent treatment impair appetite and ability to consume adequate nutrition. More detailed information on chronic illness can be found in Chapter 15. Many medications affect appetite and nutrition. These include digoxin, theophylline, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), iron supplements, antidepressants, and psychotropics. There are clinically significant drug-nutrient interactions that result in nutrient loss, and evidence is accumulating that shows the use of nutritional supplements may counteract these possible drug-induced nutrient depletions. A thorough medication review is an essential component of nutritional assessment and individuals should receive education about the effects of prescription medications, as well as herbals and supplements, on nutritional status (Chapters 9, 10). There is a strong relationship between poor nutrition and socioeconomic deprivation. According to the federal government, fewer than 1 in 10 adults age 65 and older is living in poverty. However, poverty rates among older African Americans are nearly triple those of whites, and rates among Hispanics are more than double those of whites (Butrica, 2008). Older single women are also at high risk for poverty. Older adults with low incomes may need to choose among fulfilling needs such as food, heat, telephone bills, medications, and health care visits. Some older people eat only once per day in an attempt to make their income last through the month. Programs such as the food stamp program have the potential for increasing the purchasing power of older adults who qualify, but older adults are less likely than any other age group to use the food stamp program. Of all older Americans living in poverty, approximately one in five receives food stamps (Fuller-Thomson & Redmond, 2008). Many older people may find that the amount of money required to purchase the food stamps is greater than they think they can afford, or they do not see the benefit to them. Transportation may be limited and the distance may be too great for an older person to travel to grocery stores or to acquire food stamps, which are obtained only at designated locations in cities. In addition, many older people, especially those who lived through the Great Depression, are very reluctant to accept “welfare.” Fuller-Thomson and Redmond (2008) suggest the use of focused outreach programs and public education to destigmatize the food stamp program and encourage greater use by older adults in need. Suggestions to improve the use of the food stamp program include creating mobile and satellite food stamp offices separate from welfare offices; increasing the availability of on-line application forms; creating more user-friendly applications; providing home visits by food stamp workers; providing more extensive multilingual services; and targeting information to older adults who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid, those who live in public housing, and those whose Social Security payments are below the poverty line. In addition, many older adults, particularly widowed men, may have never learned to shop and prepare food. Often, older adults have to rely on others to shop for them, and this may be a cause of concern depending on availability of support and the reluctance to be dependent on someone else, particularly family. For older adults who own a computer, shopping over the Internet and having groceries delivered offers advantages, although prices may be higher than in the stores. Fresh From the Kitchen is a service that prepares and delivers meals that do not contain additives or preservatives and can be used immediately or stored for future use (www.freshfromthekitchen.net). Older adults in hospitals and long-term care settings are more likely to experience a number of the problems that contribute to inadequate nutrition. In the United States, 40% to 60% of hospitalized older adults are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition (DiMaria-Ghalili, 2008). In addition to the risk factors mentioned earlier in the chapter, severely restricted diets, long periods of nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status, and insufficient time and staff for feeding assistance contribute to inadequate nutrition. Malnutrition is related to prolonged hospital stay, increased risk for poor health status, institutionalization, and mortality (DiMaria-Ghalili, 2008). Assessment of nutritional status to identify malnutrition and the risk factors for malnutrition is important and required by the Joint Commission. Sufficient time, care, and attention should be given to feeding dependent older people. The incidence of eating disability in long-term care is high with estimates that 50% of all residents cannot eat independently (Burger et al., 2000). Inadequate staffing in long-term care facilities is associated with poor nutrition and hydration, and as Kayser-Jones (1997, p. 19) states: “Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) have an impossible task trying to feed the number of people who need assistance.” Having one staff person for every two or three residents who need feeding assistance would allow the resident 20 to 30 minutes with the CNA (Burger et al., 2000). In a study by Simmons and colleagues (2001), 50% of residents significantly increased their oral food and fluid intake during mealtime when they received one-on-one feeding assistance. The time required to implement the feeding assistance (38 minutes) greatly exceeded the time nursing staff spent assisting residents in usual mealtime conditions (9 minutes). The use of restrictive therapeutic diets for frail elders in long-term care (low cholesterol, low salt, no concentrated sweets) often reduces food intake without significantly helping the clinical status of the resident (Morley, 2003). If caloric supplements are used, they should be administered at least one hour before meals or they interfere with meal intake. These products are widely used and can be costly. Often, they are not dispensed or consumed as ordered. Powdered breakfast drinks added to milk are an adequate substitute (Duffy, 2010). Dispensing a small amount of calorically dense oral nutritional supplement (2 calories/ml) during the routine medication pass may have a greater effect on weight gain than a traditional supplement (1.06 calories/ml) with or between meals. Small volumes of nutrient-dense supplement may have less of an effect on appetite and will enhance food intake during meals and snacks. This delivery method allows nurses to observe and document consumption. Further studies and randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of nutritional supplementation (Doll-Shankaruk et al., 2008). Attention to the environment in which meals are served is important. It is not uncommon to hear over the public address system at mealtimes: “Feeder trays are ready.” This reference to the need to feed those unable to feed themselves is, in itself, degrading and erases any trace of dignity the older person is trying to maintain in a controlled environment. It is not malicious intent by nurses or other caregivers but rather a habit of convenience. Feeding older people who have difficulty eating can become mechanical and devoid of feeling. The feeding process becomes rapid, and if it bogs down and becomes too slow, the meal may be ended abruptly, depending on the time the caregiver has allotted for feeding the person. Any pleasure derived through socialization and eating and any dignity that could be maintained is often absent (see “An Elder Speaks” at the beginning of this chapter). Older adults accustomed to certain table manners may feel ashamed at their inability to behave in what they feel is an appropriate manner. In addition to adequate staff, many innovative and evidence-based ideas can improve nutritional intake in institutions. Many suggestions are found in the literature including the following: restorative dining programs; homelike dining rooms; individualized menu choices, including ethnic foods; cafeteria style service; refreshment stations with easy access to juices, water, and healthy snacks; kitchens on the nursing units; availability of food around the clock; choice of mealtimes; liberal diets; finger foods; visually appealing pureed foods with texture and shape; music; touch; verbal cueing; hand-over-hand feeding; and sitting while assisting the person to eat. Other suggestions can be found in Box 14-2.

Nutrition and Hydration

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Age-Related Requirements

Modified MyPyramid

Other Dietary Recommendations

Fats

Protein

Fiber

Vitamins and Minerals

FOOD ITEM

SERVING SIZE

CALCIUM (MG)

Plain yogurt, fat-free

8 oz

452

American cheese

2 oz

312

Yogurt with fruit (low fat or fat-free)

8 oz

345

Milk

8 oz

300

Orange juice, calcium-fortified

8 oz

350

Dried figs

10 figs

269

Cheese pizza

1 slice

240

Ricotta cheese, part skim

cup

cup

334

Ice cream, soft serve

4 oz

103

Spinach

4 oz

139

Cooked soybeans

1 cup

298

Obesity (Overnutrition)

Malnutrition

Factors Affecting Fulfillment of Nutritional Needs

Age-Associated Changes

Taste

Smell

Buccal Cavity

Regulation of Appetite

Lifelong Eating Habits

Socialization

Chronic Diseases and Conditions

Socioeconomic Deprivation

Transportation

Hospitalization and Long-Term Care Residence