9 Nutrition and effective elimination

Introduction

Much has been written, particularly in the media, about malnutrition in hospitals and the lack of assistance some patients get to eat and drink (Age Concern 2006, O’Regan, 2009). Malnutrition is defined by the Malnutrition Advisory Group (2003) as:

According to a report by Age Concern in Age Concern, 2006, 6 in 10 older patients in hospital were either malnourished or at risk of becoming malnourished. Malnourished patients are more likely to succumb to infection, stay longer in hospital and require more intensive nursing care.

Read the original Hungry to be Heard (Age Concern 2006) and the more recent update Still Hungry to be Heard (Age UK 2010) reports to understand more about the nutritional issues facing patients when admitted to hospital and the steps that nurses and hospitals can take to prevent it.

Ensuring adequate food and fluid intake is an essential role of the nurse and it plays a significant part in the recovery of patients on acute medical wards. Even as a very junior student nurse, you will be expected to start helping patients to eat and drink and assess their nutritional status, and planning care to meet nutritional needs will become an important skill for you to learn. Nutrition and fluid management is a significant part of the Essential Skills Clusters (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2010a). At entry level to the register, it will be expected you can do the following:

• Assist patients to choose a diet that provides an adequate nutritional and fluid intake.

• Assess and monitor the nutritional status of a patient and, in partnership, formulate an effective plan of care.

• Assess and monitor the fluid status of a patient and, in partnership with them, formulate an effective plan of care.

• Assist patients in creating an environment that is conducive to eating and drinking.

• Ensure that those unable to take food by mouth receive adequate fluid and nutrition to meet their needs.

• Safely administer fluids when fluids cannot be taken independently.

Why is it such an important part of recovery?

Immune system

A number of nutrients are required to maintain a healthy immune system. This will be particularly important for the patients you are nursing on a medical ward. Some may already have a compromised immune system due to long-term medical conditions, for example HIV and tuberculosis, or as a result of treatment they have received recently or past surgical procedures such as chemotherapy/radiotherapy, transplant surgery and splenectomy. Their immune system may be compromised due to their current medical condition such as anaemia, infection and malnutrition (see Montague et al 2005).

Tissue growth and wound healing

The repair of tissues and production of new cells are essential for the body to heal itself. Protein is the essential nutrient required for this. When weight is lost quickly, muscle mass is usually lost rather than fat. A patient on bed rest due to an acute illness can lose up to 12% of their muscle strength every week. Consequently, a high-protein diet is often necessary for patients recovering from an acute illness. In order for the body to use protein efficiently, it needs to get its energy from alternative sources, so carbohydrate and fat are important sources of energy (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1 Importance of nutrition for good health

| Nutrient | Why we need it |

|---|---|

| Protein | Cell growth, wound healing, production of antibodies |

| Fats and carbohydrates | Energy sources |

| Vitamin A | Essential for healthy immune system, eyesight and skin |

| Vitamin B complex | Formation of antibodies |

| Vitamin B12 | Helps maintain a healthy nervous system, important in formation of red blood cells |

| Vitamin C | Important in the formation of collagen, aids the absorption of iron and maintains capillaries, bones and teeth |

| Vitamin D | Promotes absorption of calcium, important in maintaining healthy bones |

| Calcium | Helps build and maintain strong bones, vital for nerve function, muscle contraction and blood clotting |

| Potassium | Assists in regulation of acid-base balance, protein synthesis, metabolism of carbohydrates, normal body growth and normal electrical activity of the heart |

| Sodium | Regulates fluid balance and blood pressure |

| Iron | Prevents anaemia |

| Niacin | Helps the body to process sugars and fatty acids and maintain enzyme function, important for development of nervous system |

| Zinc | Helps with cell formation |

| Fibre | Stimulates digestive tract, prevents constipation, encourages growth of good bacteria in large intestine, slows down carbohydrate absorption |

Nutritional assessment

An assessment of a patient’s nutritional status is an important part of the initial assessments carried out when a patient is admitted to a medical ward. Each organisation will have their own policy about which assessment/screening tool is used and the timescale within which it must be completed. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE; 2006a) guideline recommends that all hospital in-patients are screened for risk of malnutrition on admission and weekly thereafter.

Assessment of nutritional status will be an ongoing process while the patient is in hospital. You may be required to repeat an assessment with a screening tool at various intervals but observation and communicating with the patient about their nutritional needs will be just as important. If you are unsure what your role is in monitoring the nutritional status of your patients, talk to your mentor about it. This will be something you could include in your learning outcomes as there are competencies in assessing nutritional status at both the second progression point and entry to the register within the Essential Skills Clusters (NMC 2010a).

Screening tools

There are many nutritional screening tools available for use. One widely used validated tool is the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool or MUST (British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) 2008). There are five steps to the MUST tool which give you an overall score between 0 and 6. The tool then provides some management guidance to inform your care plan.

Step 1 – calculating body mass index

To calculate a patient’s BMI, you need to know their height and their weight. Body mass index is an assessment of body composition and gives you an indication as to whether a patient is underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese. It should not replace your clinical judgement, but should be used to guide your assessment. The BMI chart (see http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_page2.pdf (accessed July 2011)) also gives you a score of 0 to 2 which is the first step of the MUST assessment.

When a patient is acutely unwell, it is not always easy to obtain their weight and height. The patient may know what their weight is or it may have been recorded recently at an out-patient appointment and be in their medical records. If so, this may give you a guide to work from until you are able to gain an accurate weight. However, most placement areas will have weighing scales that allow patients to sit down while being weighed or, alternatively, there may be a hoist that can weigh a patient who is bed bound. Measuring height can be more difficult if the patient is unable to stand. BAPEN (2008) recommends using ulnar length to estimate height as an alternative (see http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_page6.pdf (accessed July 2011)).

Step 2 – percentage of unplanned weight loss

To determine the percentage of your patient’s unplanned weight loss in the last 3–6 months, you will need to know what their weight was before they lost weight. The patient may be able to tell you or give you an idea of what this was. Or they may be able to tell you how much weight they think they have lost. Once you have determined whether they have lost less than 5%, between 5% and 10% or more than 10% of their body weight, you can then compare to this using the weight loss score table provided by BAPEN (see http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_page4.pdf (accessed July 2011)) which will attribute a score of 0–2 to add to the score from step 1.

Step 4 – add scores together

By adding the scores from the first 3 steps together you will get an overall score telling you the patient’s risk of malnutrition. The flow chart from BAPEN (http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_page3.pdf (accessed July 2011)) includes recommended management guidelines. The ward/department you are working in may have locally adapted guidelines so make sure that you are aware of these. Remember, as with all assessments, your clinical judgement is equally important and you may feel that although your patient doesn’t have a score indicating a high risk of malnutrition, they still require input from a dietician or close monitoring (see Aston et al (2010) for more information about decision making in practice).

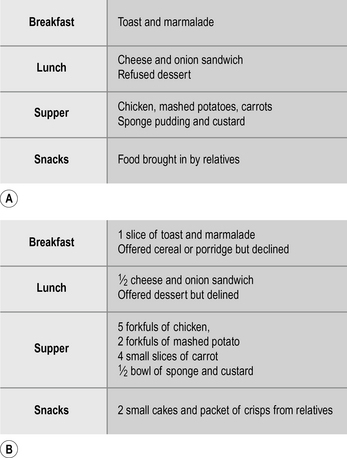

Monitoring food intake

The mealtime routine in hospitals has changed considerably over the last two decades or so with the role of the registered nurse in mealtimes decreasing and care assistants and kitchen personnel playing a greater role in serving meals and removing meal trays at the end of mealtimes (Xia & McCutcheon 2006). This has resulted in the production of best practice statements, such as the Essence of Care (Department of Health 2010) food and drink benchmark (see Box 9.1), to reinforce that it is the registered nurse’s overall accountability and responsibility to ensure patients receive adequate nutrition and hydration while in hospital.

Box 9.1 Essence of Care food and drink benchmark

People are encouraged to eat and drink in a way that promotes their health.

People are encouraged to eat and drink in a way that promotes their health.

People and carers have sufficient information to enable them to obtain their food and drink.

People and carers have sufficient information to enable them to obtain their food and drink.

People can access food and drink at any time according to their needs and preferences.

People can access food and drink at any time according to their needs and preferences.

People are provided with food and drink that meet their individual needs and preferences.

People are provided with food and drink that meet their individual needs and preferences.

People’s food and drink are presented in a way that is appealing to them.

People’s food and drink are presented in a way that is appealing to them.

People feel the environment is conducive to eating and drinking.

People feel the environment is conducive to eating and drinking.

People who are screened on initial contact and identified at risk receive a full nutritional assessment.

People who are screened on initial contact and identified at risk receive a full nutritional assessment.

People’s care is planned, implemented, continuously evaluated and revised to meet individual needs and preferences for food and drink.

People’s care is planned, implemented, continuously evaluated and revised to meet individual needs and preferences for food and drink.

People receive the care and assistance they require with eating and drinking.

People receive the care and assistance they require with eating and drinking.

Encouraging your patients to eat and drink

• Too much food on the plate – being overfaced.

• Food not presented nicely and does not look appetising.

• Food not culturally appropriate.

• Texture of food difficult to chew/swallow.

• Knife and fork difficult to hold.

• Not being able to sit up properly in chair/bed to eat.

• Positioning of bedside table/tray.

• Environmental temperature – too hot, too cold.

• Lack of energy or motivation.

• Indigestion or epigastric pain.

• Fear of diarrhoea, wind or abdominal pain.

• Food allergies or intolerances.

Chappiti U, Jean-Marie S, Chan W (2000). Cultural and religious influences on adult nutrition in the UK. Nursing Standard 14(29):47–51.

O’Regan P (2009). Nutrition for patients in hospital. Nursing Standard 23(23):35–41.

There are a number of strategies that can help encourage and monitor patients’ food intake. Some of these are nationally recognised in the UK, such as the use of red trays and protected meal times (Age UK 2010), as being best practice and you will be likely to find them happening in your medical placement area.

As you progress through your training, you are likely to have a number of competencies related to supporting patients who are having problems eating and drinking. For example, in the Essential Skills Clusters (NMC 2010a), at your second progression point it will be expected that you can do the following:

• Identify people who are unable to, or have difficulty in, eating or drinking and report this to others to ensure adequate nutrition and fluid intake is provided.

• Follow local procedures in relation to meal times, for example protected mealtimes, indicators of people who need additional support.

• Ensure that people are ready for the meal; that is, in an appropriate location, position, offered an opportunity to wash hands, offered appropriate assistance.

• Recognise and respond appropriately and report when people have difficulty eating or swallowing.

• Adhere to an agreed plan of care that provides for individual differences, for example cultural considerations and psychosocial aspects, and provide adequate nutrition and hydration when eating or swallowing is difficult.

In 2007, the Council of Europe Alliance, which included the Department of Health, RCN, BAPEN, National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) and others, produced 10 key characteristics of good nutritional care in hospitals (see Box 9.2).

Box 9.2 Ten key characteristics of good nutritional care in hospitals (Council of Europe Alliance 2007)

All patients are screened on admission to identify the patients who are malnourished or at risk of becoming malnourished. All patients are rescreened weekly.

All patients are screened on admission to identify the patients who are malnourished or at risk of becoming malnourished. All patients are rescreened weekly.

All patients have a care plan which identifies their nutritional care needs and how they are to be met.

All patients have a care plan which identifies their nutritional care needs and how they are to be met.

The hospital includes specific guidance on food services and nutritional care in its clinical governance arrangements

The hospital includes specific guidance on food services and nutritional care in its clinical governance arrangements

Patients are involved in the planning and monitoring arrangements for food service provision.

Patients are involved in the planning and monitoring arrangements for food service provision.

The ward implements protected meal times to provide an environment conducive to patients enjoying and being able to eat their food.

The ward implements protected meal times to provide an environment conducive to patients enjoying and being able to eat their food.

All staff have the appropriate skills and competencies needed to ensure that patients’ nutritional needs are met. All staff receive regular training on nutritional care and management.

All staff have the appropriate skills and competencies needed to ensure that patients’ nutritional needs are met. All staff receive regular training on nutritional care and management.

Hospital facilities are designed to be flexible and patient-centred with the aim of providing and delivering an excellent experience of food service and nutritional care 24 hours a day, every day.

Hospital facilities are designed to be flexible and patient-centred with the aim of providing and delivering an excellent experience of food service and nutritional care 24 hours a day, every day.

The hospital has a policy for food service and nutritional care which is patient-centred and performance managed in line with home country governance frameworks.

The hospital has a policy for food service and nutritional care which is patient-centred and performance managed in line with home country governance frameworks.

Food service and nutritional care are delivered to the patient safely.

Food service and nutritional care are delivered to the patient safely.

The hospital supports a multidisciplinary approach to nutritional care and values the contribution of all staff groups working in partnership with patients and users.

The hospital supports a multidisciplinary approach to nutritional care and values the contribution of all staff groups working in partnership with patients and users.

Essence of care benchmarking

The Essence of Care (DH 2010) food and nutrition benchmark sets out standards of best practice to assist healthcare practitioners in auditing their current standard of nutritional care and implementing improvements in nutritional care.

If any of these are in place in your placement area, ask your mentor if you can be involved in carrying out an audit as part of the essence of care benchmarking or another local audit of nutritional care and practice. The essence of care benchmarks can be found at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_119969 (accessed July 2011).

The role of the dietician

The role of the hospital dietician is to assess and advise on the nutritional care of patients with special dietary needs. These may be needs that are associated with a chronic medical condition, such as diabetes, or may be patients whose nutritional intake is compromised because of their acute medical condition such that they require a special or modified diet or supplementary or artificial feeding. Find out who the dietician is in your placement area. Speak to your mentor about possibly spending some time with the dietician to understand their role and the variety of supplementary and artificial feeding options available in your organisation. Box 9.3 gives some examples of departments or staff associated with nutrition in hospital that you could meet or spend time with during your placement.