CHAPTER 28 Nursing the unconscious patient

Introduction

Defining consciousness

Hickey (2003) defines consciousness simply as ‘a state of general awareness of oneself and the environment’ and includes the ability to orientate towards new stimuli. The individual is awake, alert and aware of their personal identity and of the events occurring in their surroundings. Deep coma, the opposite of consciousness, is diagnosed when the patient is unrousable and unresponsive to external stimuli; there are varied states of altered consciousness in between the two extremes (Box 28.1). Even during normal sleep, an individual can be roused by external stimuli, in comparison to the person in a coma.

Box 28.1 Information

Adapted from Hickey (2003).

Continuum of levels of consciousness

Anatomical and physiological basis for consciousness

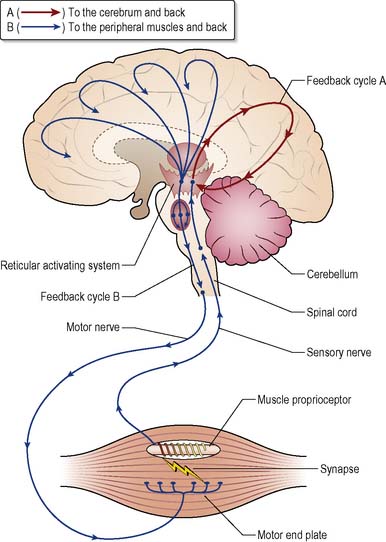

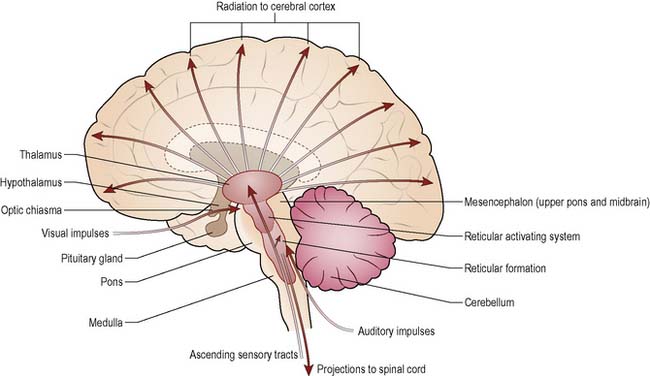

The reticular formation (RF) and the reticular activating system (RAS) (Figure 28.1) are responsible for collating and transmitting motor and sensory activities and controlling sleep/waking cycles and consciousness.

Figure 28.1 Mid-sagittal section of the brain, showing the reticular activating system and related structures.

The reticular formation (RF)

The RF is a network of neurones within the brain stem (Waugh & Grant 2001) that connect with the spinal cord, cerebellum, thalamus and hypothalamus. The RF is involved in the coordination of skeletal muscle activity, including voluntary movement, posture and balance, as well as automatic and reflex activities that link with the limbic system.

The reticular activating system (RAS)

The RAS is a physiological component of the RF and the neurones which radiate via the thalamus and hypothalamus to the cerebral cortex and ocular motor nuclei. It is concerned with the arousal of the brain in sleep and wakefulness (Marieb 2004). Two main parts have been identified (Guyton & Hall 2000): the mesencephalon and the thalamus.

The mesencephalic area is composed of grey matter and lies in the upper pons and midbrain of the brain stem. Stimulation produces a diffuse flow of nerve impulses which pass upwards through the thalamus and hypothalamus, radiating out across the cerebral cortex to provoke a general increase in cerebral activity and wakefulness (see Figure 28.1). Signals from different areas in the thalamus initiate selective activity in the cortex protecting the higher centres from sensory overload (Marieb 2004). The reticular nucleus, which receives impulses from the RF, surrounds the front and sides of the thalamus. It is this nucleus that sends inhibiting messages back to the thalamic nuclei using the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

In order to function, the RAS must be stimulated by input signals from a wide range of sources. These are transmitted via the spinal reticular tracts and various collateral tracts from all the modalities of sensation, e.g. the specialised auditory and visual tracts (see Ch. 9). The RAS is also affected by signals from the cerebral cortex, i.e. the RAS may first stimulate the cerebral cortex, and the cortical areas responding to reason and emotion may ‘modify’ the RAS, either positively or negatively, according to the ‘decision’ of the cerebral cortex.

Sleep is induced by a hormone called melatonin which is synthesised from serotonin in the pineal gland. When an individual is in a deep sleep, the RAS is in a dormant state. However, almost any type of sensory signal can immediately activate the RAS and waken the individual, for example when daylight is detected by the retina of the eye, impulses are sent to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, activating sympathetic nerve fibres that will inhibit the secretion of melatonin in the pineal gland. This is called the ‘arousal reaction’ and is the mechanism by which sensory stimuli wake us from deep sleep (Guyton & Hall 2000). Lesions in this area can cause excessive sleepiness or even coma (Fitzgerald 1996).

The feedback theory

The cerebrum regulates incoming information by a positive feedback mechanism (Guyton & Hall 2000). A second feedback cycle that stimulates proprioceptors in skeletal muscles is also shown in Figure 28.2.

After a prolonged period of wakefulness, the synapses in the feedback loops become increasingly fatigued, reducing the level of stimulation and activity directed to the reticular activating system and thereby inducing a state of lethargy, drowsiness and eventually sleep (Guyton & Hall 2000). Figure 28.2 illustrates a number of activating pathways passing from the mesencephalon upwards.

States of impaired consciousness

There is no international definition of levels of consciousness but, for assessment purposes, differing states of consciousness can be considered on a continuum between full consciousness and deep coma (Hickey 2003) (see Box 28.1). Consciousness cannot be measured directly but can be estimated by observing behaviour in response to stimuli. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Teasdale 1975) is widely used as an assessment tool and helps to reduce subjectivity during assessment of conscious level (see p. 741).

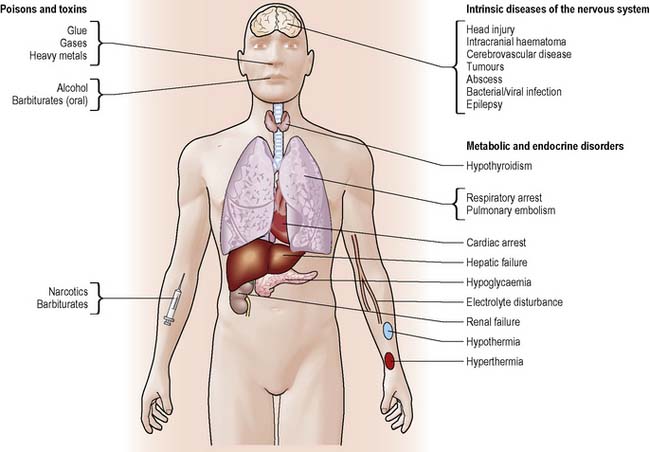

Impaired states of consciousness can be categorised as acute or chronic. Acute states, for example drug or alcohol intoxication, are potentially reversible whereas chronic states tend to be irreversible as they are caused by invasive or destructive brain lesions. Deterioration or improvement will depend on a number of factors such as the mechanism, extent and site of injury, age, previous medical history and length of coma. Common causes of altered level of consciousness are illustrated in Figure 28.3 (see www.headway.org.uk).

Reduced awareness

Reduction in awareness reflects generalised brain dysfunction, as seen in systemic and metabolic disorders (see Figure 28.3). These disorders interfere with the integrity of the RAS, affecting the patient’s arousal response.

In the early stage, subtle changes may occur in the patient’s behaviour. They may exhibit signs of hyper-excitability and irritability, alternating with drowsiness, progressing to confusion and increased levels of disorientation. Minor disturbance such as irritability can easily go undetected and comments from a relative such as ‘she does not seem to recognise me today’ may denote a subtle change in behaviour that requires further investigation. Martin (1994) suggests that nurses who are expert in the care of head-injured patients can identify cues which indicate behavioural, cognitive, motor and sensory changes even in mild brain dysfunction.

Cognitive disabilities, e.g. poor concentration or short-term memory problems, may only become apparent when a patient returns home. These can cause emotional distress for both the patient and family, particularly if they go unheeded and help is not provided. The primary care team plays a major role in supporting patients following acquired brain injury, facilitating referral to specialist agencies (see www.bann.org.uk).

Delirium

Delirium is a fluctuating mental state characterised by confusion, disorientation, fear and irritability. The patient may be talkative, loud, offensive, suspicious or extremely agitated. This behaviour reflects generalised brain dysfunction due to interference with the RAS, affecting the arousal mechanism (Siddiqi et al 2007). Patients will present with a range of symptoms including:

Stupor

The term stupor describes a state whereby the patient is quiet and tends not to move, except in response to vigorous and repeated noxious stimuli (Hickey 2003).

Chronic states of impaired consciousness

Dementia

Although dementia is an irreversible condition, new drug therapies such as donepezil (Aricept®) are being used successfully to delay onset of the disease. Patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus may be helped by insertion of a ventricular shunt (Wilson & Islam 2004, Dalvi 2010; see also Life NPH in Useful websites, p. 756).

Vegetative state

Vegetative state (VS) is a term used to describe a condition that may occur following a severe brain injury, where there is extensive damage to the cerebral cortex. Although the patient has sleep/waking cycles, the higher centres of the brain are destroyed. Physiologically, the brain stem is functioning but the cerebral cortex is not, and patients can survive for several years requiring full-time nursing care. The British Medical Association (1996) recommends ‘that the diagnosis of irreversible Permanent Vegetative State (PVS) should not be considered or confirmed (and therefore treatment not be withdrawn) until the patient has been insentient for 12 months’. Some neuro-rehabilitation units use a structured technique for assessing various sensory aspects of communication, movement awareness and wakefulness, known as SMART (sensory modality assessment and rehabilitation technique – www.smart-therapy.org.uk/), to enable clinicians to make a more accurate diagnosis of patients they suspect may be in PVS.

There is ongoing debate, both in the UK and other countries, about the moral, ethical and legal issues surrounding the care and treatment of these individuals and the dilemma posed by some patients to ‘the right to die’ and withdrawal of treatment has received considerable professional, public and political attention over recent years (Porter 2005) (see www.ethics-network.org.uk).

Locked-in syndrome

This occurs when there is damage to the pons in the brain stem, resulting from cerebral vascular disease or trauma, paralysing voluntary muscles without interfering with consciousness and cognitive functions. The patient is unable to speak and is sometimes unable to breathe spontaneously, the latter requiring mechanical ventilation and respiratory support. However, the patient is able to control vertical eye movements and blinking and may be able to use these movements to develop a simple communication system. It is important to remember that the patient is cognitively aware, even if they appear to be mentally and physically inert. For further information about PVS and locked-in syndrome, see Randall (1997), Smith (1997) and Royal College of Physicians (2003).

Assessment of the nervous system

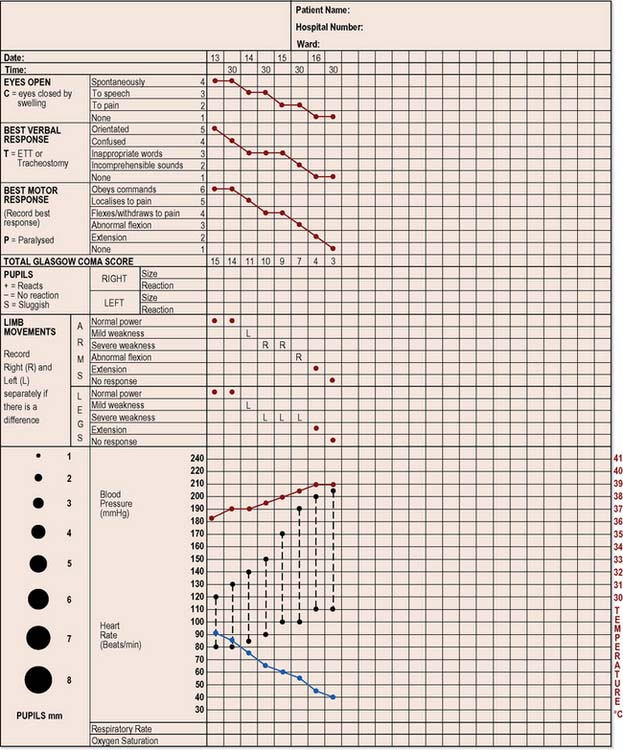

The need to assess conscious level may arise at any time, in any ward, in any hospital. In 1974, Teasdale and Jennett developed the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), a process used throughout the UK and worldwide as part of the neurological assessment and ongoing observation of the patient (see Figure 28.4). It provides a standardised approach to observing and recording adverse changes in the patient’s level of consciousness, so that appropriate action can be taken (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE] 2003) (Box 28.3).

Box 28.3 Evidence-based practice

The Neurological Observation Chart

The Glasgow Coma Scale

Each of these is independently assessed and recorded on a chart (Figure 28.4). The patient’s response is recorded with a dot joined with straight lines to form a graph, making it easier to assess whether the patient is improving or deteriorating. The frequency of recording will be based on the patient’s clinical condition. The best response for each of the three aspects is recorded as a numerical score. In the case of eye opening, the best response would score a 4, the best verbal response would score a 5 and the best motor responses would score a 6. The lowest response for each of the three parameters is a score of 1. Thus the highest total score is 15 and the lowest is 3.

Eye opening

To pain = scores 2. A gentle shake of the patient’s shoulder may be sufficient to elicit a response. If the patient still fails to open their eyes, a painful stimulus must be used. Pressure is applied to the lateral inner aspect of the second or third finger using a pen or pencil, for a maximum of 15 seconds (Figure 28.5). Nail bed pressure is contraindicated as it will cause excessive bruising.

Possible assessment problems

The nurse needs to be aware if the patient has any hearing deficits because if their eyes are closed, this will affect the initial response. Congenital deficits of the eye or previous enucleation (see Ch. 13) must also be taken into account. Inability to open the eyes due to bilateral orbital oedema, tarsorrhaphy (where upper and lower eyelids are sutured together), or ptosis (palsy of cranial nerve III) should be recorded as ‘C’ (closed) on the chart.

Verbal response

This assesses the area of the brain associated with receptive and expressive speech.

Motor response

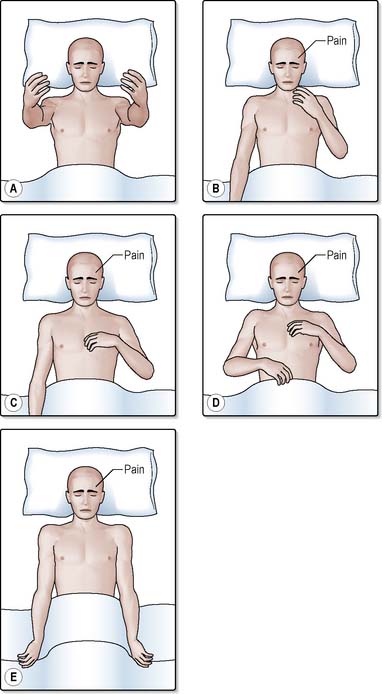

This assesses the patient’s best motor response. Only the best response from the arms is recorded as leg responses to pain are less consistent and may be confused with a simple spinal reflex. The responses described below are shown in Figure 28.6.

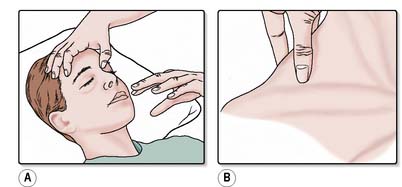

Localises to pain. Score = 5. If the patient does not obey commands, an external stimulus must be applied. In the absence of any facial, orbital or skull fractures, pressure is applied with the flat of the nurse’s thumb over the cranial nerve underlying the supraorbital ridge under the eyebrow (Figure 28.7a). Pressure is gradually increased for a maximum of 15 seconds. Providing the patient has not sustained a cervical fracture, the ‘trapezius pinch’ (Figure 28.7b) is a useful alternative; the trapezius muscle (the large triangular muscle of the neck and thorax) is squeezed between the nurse’s fingers and thumb. The response is recorded as ‘localising to pain’ if the patient moves their arm across the midline, to the level of the chin, in an attempt to locate the source of the pain (Figure 28.6b). During the course of the day, the patient may display a localising response to other sources of irritation, e.g. suctioning, nasogastric tube or urinary catheter.

Figure 28.7 Applying a central painful stimulus. A. Supraorbital ridge pressure. B. Trapezius pinch.

Recording other measurements

A neurological assessment includes the recording of additional measurements as follows:

Vital signs

Blood pressure and pulse

A rising blood pressure (elevated systolic pressure), widening of the pulse pressures and a slowing pulse (see Ch. 9), known as ‘Cushing’s response’, is a very late sign of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) and there may have been other signs such as subtle alterations in behaviour or fluctuating level of consciousness which could have indicated a deterioration in neurological status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree