CHAPTER 26 Nursing the patient undergoing surgery

Introduction

Patterns of surgical care

National figures demonstrate that around 8 million surgical operations are carried out in the UK every year (National Patient Safety Agency 2008). In the past it was common to admit patients on the day prior to surgery and keep them in hospital beyond the acute phase of recovery. However, the length of time patients now spend in hospital preparing for, and recovering from, elective surgery has greatly decreased (Mitchell 2007a). Advances in surgical technology and anaesthesiology have allowed previously lengthy operations to be completed more quickly and recovery times have become shorter. Many procedures are now undertaken using laparoscopic, robotic and keyhole surgery. The use of lasers, angiographic stenting and ultrasound techniques has increased; for example, carotid artery stenting offers an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients at high risk of intra-operative complications (Zeebregts et al 2009). These techniques also allow interventions to be carried out at the same time as diagnosis, reducing the need for repeated anaesthesia. Improvements in anaesthesia techniques, such as regional anaesthesia and short-acting drugs with minimal side-effects (e.g. remifentanyl), allow larger numbers of patients to be ready for discharge in a matter of hours following surgery (Shnaider & Chung 2006).

Currently around 60% of surgical procedures are undertaken as outpatient or day cases (NHS Scotland 2010), and it is likely that in the future there will be further increases in the number and range of minimally invasive procedures available. Nurses must refine their skills and knowledge to be able to provide appropriate physical and psychological support to enable these patients to care for themselves following discharge (Mitchell 2007a).

An increase in the number of referrals for minor surgical procedures has also provided the opportunity to extend nursing roles to meet present and future demands. Martin (2002) describes the role of a nurse practitioner (NP) who provides a one-stop minor surgery clinic for the removal of moles, cysts, lipomas and papillomas using local anaesthetic. A patient satisfaction survey of this service reported that although 20% of patients had not expected a nurse to undertake their surgery, all patients found it acceptable to be operated upon by an NP. Developments in nurse-led initiatives such as pre-operative assessment units (Walsgrove 2006) and nurses carrying out endoscopies (Smith & Watson 2005) further expand the role of nurses in peri-operative care.

The demographic profile of the population in the UK is changing. With greater average life expectancy and improvements in treatments for chronic illness, there are now increasing numbers of older people in our society. This results in an increase of older adults presenting for surgery (Leung & Dzankic 2001, Sear 2003, McArthur-Rouse & Prosser 2007). Ageing affects all of the body systems and the most affected are the cardiovascular, renal and respiratory systems. This means that older patients may have reduced physiological reserves to maintain homeostasis during a period of acute illness such as surgery. Frail older adults are susceptible to hospital acquired, or nosocomial infections such as pneumonia, Clostridium difficile and complications of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Leung & Dzankic (2001) found that approximately 21% of patients over the age of 65 develop one or more in-hospital postoperative complications involving the cardiovascular, neurological or respiratory systems. Older adults are also more likely to suffer from one or more co-existing diseases (known as co-morbidities) which also increases the risk of developing postoperative complications (Williams et al 2007). For example, patients with cardiovascular disease are more at risk of developing myocardial infarction (MI) or arrhythmias following surgery (Sear 2003).

Therefore patients nursed on acute surgical wards have increasingly complex health care needs. Structured care approaches such as protocols, clinical pathways and algorithms are frequently used to organise knowledge and guide patient care, but nurses must still be able to undertake accurate assessments and make decisions about patient management in order that complications are recognised early and expert assistance is sought rapidly (McArthur-Rouse & Prosser 2007). Pirret (2003) describes a pre-operative scoring system used by nurses to identify patients at risk of postoperative complications. Once identified, at-risk patients can be admitted electively to high-dependency (HDU) or intensive care units (ICU) to undergo close postoperative monitoring.

Nurses must also consider the additional burden of co-existing disease on the patient. In a study of 20 patients requiring total hip or knee joint replacement it was found that co-morbidity management was not consistently included in care plans during the acute phase of hospitalisation (Williams et al 2007). Patients with co-morbidities such as heart failure, diabetes or Parkinson’s disease were expected to progress at the rate specified in standard clinical pathways, despite reporting higher rates of pain and fatigue postoperatively. Also, advice given on the day of discharge mainly focused on the joint surgery unless complications from the pre-existing conditions had arisen during the hospital stay. Peri-operative care of older surgical patients and those with co-morbidities is thus becoming an increasingly important part of nursing practice.

Patients are increasingly involved in their own care (Scottish Executive 2003). The patient facing surgery should be seen as a partner in the care process and participate in the planning and evaluation of health care (Edwards 2002). This may involve choosing where they receive surgery. In 2003 the Department of Health introduced a scheme to ensure that patients who are waiting for heart surgery or angioplasty receive their surgery more quickly and choose where they have this treatment (DH 2005). Patient participation is essential to the success of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for colorectal surgery (Wright et al 2009). Nursing staff spend considerable time with patients in the pre-operative period to ensure that they understand the goals of the programme which include early mobilisation and nutrition in the postoperative period. This laparoscopic-assisted colonic surgery has reduced most patients’ stay from 7–10 days to 3–5 days (Kehlett & Wilmore 2002).

Integral to the care of patients facing surgery is the role of teamwork (Hughes & Mardell 2009). Nurses in surgical wards and departments must work collaboratively with many members of the interprofessional team so that continuous and high-quality care can be provided. Typically this will include surgeons, anaesthetists and theatre staff, but also allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and radiographers are often integral to the diagnostic and rehabilitation processes.

Pre-surgical care

Classification of surgery

Some patients experience periods of ill health or disability before undergoing an operation; others experience sudden illness or injury that necessitates immediate surgery. Around 15% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer are operated on following an emergency presentation (Taylor 2008), as in the case of Mr Shah.

![]() See website Case study – Mr ShahThe degree of urgency of a surgical intervention is a useful criterion for its classification and prioritisation. A patient such as Sylvia who has uncomplicated gallstone disease would normally not be classified as ‘urgent’ but would be put on a waiting list and admitted ‘electively’.

See website Case study – Mr ShahThe degree of urgency of a surgical intervention is a useful criterion for its classification and prioritisation. A patient such as Sylvia who has uncomplicated gallstone disease would normally not be classified as ‘urgent’ but would be put on a waiting list and admitted ‘electively’.

![]() See website Case study – Sylvia

See website Case study – Sylvia

Presenting for surgery

Personal definitions of health and ill health and the decision to seek treatment are influenced by factors such as previous experience, social context, perceived severity of illness and judgements as to whether treatment would be beneficial (Box 26.1).

In Box 26.2 Mr A had made a voluntary decision to seek treatment based on information obtained through the internet, and from talking with his partner. The accessibility of the internet has meant that more and more of the public use it as a source of information. Patients may present with an increasingly sophisticated level of knowledge about procedures. However, there are no standards guaranteeing the quality of information from the internet, and some of the information Mr A found may not be from a medical source or be research based.

Pathways and progress

![]() See website Case study – Mr Shah

See website Case study – Mr Shah

Patients may also be transferred from other wards. For example, a patient on a medical ward may undergo investigations which lead to a diagnosis necessitating surgical treatment and therefore transfer to a surgical ward. A few patients admitted as emergencies may go straight to theatre from the ED and from there to the surgical ward following the operation. Some patients may need to go back to theatre or the intensive therapy unit (ITU) if their condition deteriorates or requires further intervention. Many hospitals now have specialist surgical high-dependency unit facilities where patients can be closely monitored for the first 24–48 h following their operation. These units usually have a higher ratio of nurses to patients than general ward areas. HDUs are thus often used for patients following major surgery or where pre-existing medical conditions predispose them to complications (DH 2000, Sheppard & Wright 2006). Occasionally, convalescence or rehabilitation may be required in another ward or hospital, e.g. following amputation or neurosurgery. However, increasingly these services can be provided by community health care teams.

A substantial morbidity exists among patients on waiting lists for surgery. Patients with gallstone disease requiring elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy make up a significant percentage of those awaiting surgery in the UK. Whilst on the waiting list, some patients may suffer recurrent bouts of severe abdominal pain and require emergency hospitalisation (Somasekar et al 2002, Lawrentschuk et al 2003). Waiting for treatment not only causes patients pain, distress and anxiety but can also have expensive consequences, e.g. absence from work and emergency hospital admissions (DH 2001a). In the case of Mr Rutherford he has experienced some episodes of temporary weakness and loss of vision that prompted him to see his GP.

![]() See website Case study – Mr Rutherford

See website Case study – Mr Rutherford

Informed decision making

The decision to operate

Once the outcome of investigations is known and the risks to the patient of surgery assessed, the surgeon can make a definite or provisional diagnosis and recommend a course of action. This may involve diagnostic, curative or palliative surgery, a combination of these, or no surgical intervention at all. If the patient can be treated as successfully without surgical intervention, then the relevant alternatives will be pursued. It may appear that it is the medical staff who make decisions about the course of treatment to be given. However, whereas the doctor decides what treatment appears to be the most appropriate, it is the informed patient who must make the final decision as to what treatment is accepted (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC] 2008). Patients may feel pressure from family or health care professionals to undergo surgery if it offers the only chance of cure, and it is important to establish the true wishes of the individual (Myatt 2006).

Informed consent

Consent is a patient’s agreement for a health professional to provide care (DH 2001b). The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC 2008) states that every adult has the right to consent or refuse treatment unless they are:

When patients undergo any intervention or procedure, they must give consent. Touching someone without their consent and without lawful justification could be construed as trespass, civil assault or battery (Baxter et al 2002). In practice, it is preferable to obtain verbal rather than written consent from the patient for low-risk procedures, such as a chest X-ray or the administration of suppositories. However, when a patient is to undergo surgery or any invasive procedure, and when a general or local anaesthetic is required, it is advisable and standard practice to obtain written consent. As the medical team are in charge of these procedures, they are ultimately responsible for obtaining the written consent from the patient. Consent forms are traditionally used within hospitals and clinics to document that the patient and the medical staff have discussed and agreed the proposed treatment (Griffith & Tengnah 2008). However, a signed consent form does not give any indication of what the patient was told, what was consented to or whether there was a meaningful understanding as to what they were agreeing to (DH 2001b). The doctor signing the consent form with the patient has therefore to ensure that:

It is suggested that a record of the discussion and an explanation of the treatment are recorded in the patient’s notes to corroborate that consent has been obtained (Griffith & Tengnah 2008).

The role of the nurse

The nurse has an important role to play in obtaining consent prior to surgery. For a patient to give valid consent, they must comprehend fully what they are consenting to, i.e. their consent must be informed. The nurse can provide the team with knowledge of the individual’s need for information and comprehension of the information given. The nurse will also provide the patient with information about the procedure and the recovery period, and may be able to clarify points previously discussed between patient and doctor. Where nurses do take consent, they should receive thorough training (NMC 2008). In Mr A’s case (see Box 26.2), specialist family planning nurses provided pre-operative information and obtained his consent for his vasectomy. There may also be occasions when the nurse is in charge of a particular procedure and must therefore obtain written consent from the patient, for example, where nurses undertake endoscopy (Smith & Watson 2005).

The need for informed consent raises legal and ethical issues for both nurses and patients. The current social climate emphasises consumerism and patients’ rights. Patients have an increased desire to be ‘partners in care’, i.e. to be well informed and to take responsibility for their own health (Scottish Executive 2003). Patients have the right to be given an adequate explanation of proposed treatment, including any risks and alternative treatments. Nurses have a vital role to play in ensuring a patient’s need for information is met and that full discussion takes place (Griffith & Tengnah 2008, NMC 2008).

However, there may be occasions when the patient is less than fully informed. The depth and complexity of information held by medical staff may be overwhelming for a lay person to absorb and understand. There is now heightened awareness of the need to explain the potential effects of treatments – adverse as well as beneficial. The risks of some procedures are now clearly stated on the consent form itself. When responding to specific questions about risks a health professional is required to answer fully and truthfully regardless of the likelihood of the risk materialising (Griffith & Tengnah 2008). Both the chance of occurrence and the severity of potential adverse effects of the procedure must be addressed.

Nurses who think that patients are insufficiently informed should discuss their concerns with the surgeon, but not in the presence of the patient. Booth (2002) suggests that nurses are in a good position to mediate between doctors and patients, to facilitate two-way communication, and to prevent patients becoming passive recipients of the doctor’s expertise. However, it is more usual for nursing and medical staff to be sensitive to the individual needs of the patient and to work collaboratively with the patient and family.

In some cases, the patient may be too ill to comprehend what is proposed and thus to give informed consent. Also, within society there are groups of individuals who are unable to make decisions for themselves or who cannot communicate these decisions (Box 26.3). This inability is known as ‘mental incapacity’. In Scotland, any issue relating to the welfare of an ‘incapable adult’ is governed by The Adult with Incapacity Act (Scotland) 2000 (HMSO 2000). Similar legislation has been introduced in England and Wales in the form of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007).

Box 26.3 Reflection

Decision making

How can nursing staff clarify where decision making responsibility lies in the following cases?

Any refusal of treatment must be respected, provided the decision is appropriate in the circumstances. The patient’s relatives have no legal right to give or, more importantly, to refuse consent. Lifesaving procedures can be performed without consent using the doctor’s clinical privilege. A doctor has the power to take such action as is necessary, but only the minimal amount of treatment should be undertaken to alleviate the particular emergency, and should follow established practice (Griffith & Tengnah 2008). Good practice would suggest that the relatives are consulted and a decision is made in the patient’s best interests.

Similarly, relatives have no legal rights in determining whether information should be given to or withheld from the patient. In fact, the doctor or nurse would be in breach of confidentiality if they were to tell the relatives first, or to tell them at all, without the patient’s expressed consent. Where information is withheld from the patient, the patient cannot consent to its being divulged (NMC 2008). There is an NHS code of practice on protecting patient confidentiality (NHS Scotland 2003).

When a patient is too ill to be told, or cannot give informed consent, medical and nursing staff must carry out their professional duty to act in the patient’s best interests, whilst considering the wishes of the relatives. The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses (NMC 2008) provides guidelines on professional practice. Nurses are required to follow the Code in terms of acting to safeguard the patient’s interests and to work in a collaborative and cooperative manner with other health care professionals. It is essential that nurses are familiar with the Code and apply it in practice. Guidelines on informed consent have also been produced for doctors and nurses (DH 2001b, General Medical Council 2008). A discussion of the implications of the Mental Capacity Act in relation to anaesthesia and critical care can be found in White & Baldwin (2006).

Pre-operative preparation

![]() See website Critical thinking question 26.1

See website Critical thinking question 26.1

Pre-operative assessment begins when the decision to perform surgery is made (Scott et al 2007). Pre-preparation involves assessment and providing information. For more about the aims of pre-operative assessment and the role of pre-operative assessment clinics see Walsgrove (2006).

Assessment

Blood samples are required prior to many surgical procedures; tests may include haemoglobin levels, clotting studies, urea and electrolytes. If a blood transfusion is anticipated, cross matching will be carried out. An audit of 100 patients at a pre-assessment clinic in England showed that many were unclear about the investigations they would undergo (Jolley 2007). Approximately half the patients (53%) realised that tests may be necessary but were not sure what was being checked. Only 11% of the sample understood why they needed investigations despite written information having been sent out in advance. Nursing staff should be able to give simple and specific information about pre-operative investigations.

The risk of surgery to the patient is determined by:

The surgeon and anaesthetist will undertake an assessment of the patient and establish whether the risks are negligible, low, intermediate or high risk. A simple classification scale is produced by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (Box 26.4; ASA 2005).

Box 26.4 Information

As Sylvia is young and physically healthy she satisfies the recognised criteria for day surgery (Royal College of Surgeons of England 1992) and has been considered for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the day surgery unit.

![]() See website Case study – Sylvia

See website Case study – Sylvia

However, patients with a history of jaundice, abnormal liver function tests or a dilated common bile duct may be considered as ‘high risk’ and require an open cholecystectomy (Mitchell 2007b). Sylvia had attended a pre-assessment clinic at her local hospital prior to surgery where the nurse identified that Sylvia had difficulty in arranging childcare on the scheduled date of surgery. The nurse was able to provide Sylvia with appropriate information about postoperative recovery, including the potential risks of driving on the day of surgery and advising her that another adult should stay with her overnight once she was discharged home. The nurse also explained that conversion to an open procedure was necessary for a few patients. This can be due to adhesions or if the surgeon has difficulty in visualising the anatomy of the gall bladder, or it was acutely inflamed (Graham 2008). If this was the case Sylvia would not be able to go home as planned on the same day. It is important that nurses undertake assessment of the patient’s home circumstances to gain a full picture of their needs.

Giving information

The majority of patients are anxious on the day of surgery (Mitchell 2007a, Pritchard 2009). Hollaus et al (2003) suggest that pre-operative anxiety is prevalent regardless of the patient’s diagnosis. Anxiety may result from fear of the unknown, separation from friends or family, fear of a diagnosis such as cancer or even fear of dying. Also patients may feel that they lack control in the unfamiliar clinical environment (Stirling 2006). Some patients reported that they feared a mask would be placed over their face to administer the anaesthetic (Mitchell 2007a). Nurses can reassure patients that induction of anaesthesia is usually administered intravenously. Anxiety may affect patients’ vital signs, elevating the pulse, respiratory rate and blood pressure, providing baseline recordings that are not representative of usual values. If a patient appears anxious, particularly on admission, or immediately prior to theatre, it is wise to repeat any observations that are not within normal parameters. Patients who are very anxious may seek constant assurance and attention from the nursing staff. Pritchard (2009) warns that there may be a tendency for staff to label such patients as ‘difficult’ or ‘demanding’, when in fact they are frightened. Nurses should offer anxious patients support and attempt to relieve their concerns.

Reducing pre-operative anxiety and stress is not only desirable on humanitarian grounds, but it also promotes recovery. Giving the patient information and emotional support pre-operatively was shown to reduce pre- and postoperative anxiety substantially and reduce postoperative pain, stress, anxiety and infection (Hayward 1975, Boore 1978). More recently it has been found that attending a standardised information session prior to hip surgery significantly reduces anxiety and is associated with less postoperative pain (Giraudet-Le Quintrec et al 2003). Garretson (2004) suggests that more pre-operative information programmes should be developed to enhance the patient experience but found that many centres still did not have formal policies on pre-operative information giving and patients were still arriving for surgery uninformed and anxious.

Lack of information has been found to be a major source of dissatisfaction among day-case patients. Costa (2001) investigated the lived experience of ambulatory surgery patients and suggested that many did not have a clear picture about what to expect pre-operatively, postoperatively and throughout their convalescence at home. Mitchell (2007a) found that 42% of day surgery patients in the UK were not offered a pre-assessment visit. Pre-admission information allows for emotional adjustment over a longer period and enables patients to share information with, and seek support from, their families.

Nurses are ideally placed to play a major role in reducing pre-operative anxiety and need to devise approaches to delivering effective pre-operative teaching in a reduced time frame (Pritchard 2009). Garretson (2004) suggests that a pre-operative information session should include the following elements:

However, it is also important that patients and family members receive information most useful to them for postoperative care activities at home after discharge. A literature review by Pieper et al (2006) identified that three main areas for which patients sought information were postoperative pain management, wound/incision care and activity guidelines. Patients may also be concerned about where they should report on the morning of surgery or whether they should arrive having fasted or bring their medications with them. Mitchell (2007a) outlines a useful framework for patient admission and discharge for day surgery.

Patients should receive information at an appropriate level and on matters that concern them – not simply on what the nurse assumes they will be anxious about. Giving patients large volumes of information will not necessarily lead to a reduction in anxiety for all patients. For some patients too much information may become confusing and lead to heightened anxiety (Mitchell 2007a). Information given should be dependent on the individual patient’s preference and need, and be of high quality. Way et al (2003) describe the implementation of a group approach to pre-admission preparation of patients awaiting elective cardiac surgery. Patients reported that meeting and talking with other patients in advance of the operation helped them to cope with the surgery, and postoperative recovery was similar to patients who had received individual sessions. However, this approach may not be appropriate in other circumstances, such as emergency surgery, or when anxiety and pain interfere with the patient’s ability to participate.

A small but increasing number of patients are undergoing surgical procedures whilst awake. A phenomenological study of patients undergoing awake craniotomy for intra-operative mapping of brain tumours by Palese et al (2008) highlighted that patients needed to feel in control of the situation and understand what is happening intra-operatively. Further research is required to explore the most appropriate information and planning for such patients.

Skilled, systematic and sensitive assessment is essential in determining what is important for the individual. Open questioning can determine what the patient already understands and what they would like to know more about. Simply giving a factual account of what will occur is insufficient. Patients want to know what to expect and how it will feel. They also need the opportunity to discuss their fears and worries. Nurses can use this opportunity to provide patient teaching on postoperative care issues such as the use of patient controlled analgesia (PCA) or deep breathing and leg exercises. When and how information is given will influence its effectiveness. Many patients have difficulty in remembering verbal information. While a personal, verbal explanation is invaluable in that it allows for feedback from the patient, it is difficult to recall over time (Mitchell 2007a).

Pre-admission booklets for surgical patients can be beneficial in reducing patient anxiety and improving outcomes. Information can also be presented using other media such as video (Garretson 2004). However, there may always be patients who do not wish to watch information videos about their proposed procedure immediately prior to surgery (Hyde et al 1998). Information leaflets or videos are not, therefore, a substitute for personalised explanation but do provide a constant reference source and can prepare patients to use their contact time with nurses more effectively. This allows the nurse to focus on areas of concern and to devote more time to counselling than to information giving, as in reality it is often difficult to complete both tasks well in the busy pre-operative period. Pre-operative information booklets should be easy to read without being patronising in tone (Markham & Smith 2003). Print size, reading ease and vocabulary should all be considered and the use of jargon avoided. Some departments produce their own booklets giving general information about wards and surgery and have leaflets about specific operations which can be given to the patient prior to admission.

Pre-operative education aims to produce a well-informed consumer, to promote healthy choices and to reduce anxiety. The informed patient is better equipped to make good decisions about their care and to discuss treatment fully and openly with staff. Information also serves to produce a more autonomous patient. One must then respect the view that the well-informed patient has the right to reject advice or treatment against professional judgement for personal reasons (Griffith & Tengnah 2008). What the professional advocates may conflict with what the patient wants. Simply informing someone of an objective fact that appears rational (e.g. smoking causes lung cancer) will be insufficient in some cases to promote healthy behaviour or coping mechanisms (Donovan & Ward 2001). It is also important to address the information needs of family members because they may have a role in providing support and care at home (Paavilainen et al 2001).

Safe preparation for anaesthesia and surgery

In the pre-operative assessment the patient’s specific needs and potential problems may be identified. The general risks associated with anaesthesia and surgical intervention will also be taken into account in any related medical or nursing procedure. Patients undergoing surgery require medical assessment, the nature of which will depend on the extent of surgery, the age of the patient and on any pre-existing medical conditions. In some centres, an initial assessment is carried out by nursing staff so that patients most in need of anaesthetic review, such as those with poor exercise tolerance, asthma or previous problems during anaesthesia, are seen promptly (Hilditch et al 2003).

Minimising the risk of infection

There is a strong association between infection and surgery (SIGN 2008). Patients may develop infection at the site of their surgery (surgical site infection – SSI) which may include wound infections, infection of body cavities (e.g. peritonitis), bones, joints, meninges or any of the soft tissues involved in the operation. Infection can also occur at sites away from the operation, e.g. chest infection associated with hypoventilation at general anaesthesia, urinary tract infection from bladder catheterisation, or systemic sepsis following the bacteraemia of any invasive procedure. Attention to hygiene, asepsis, physiotherapy, antibiotics and bowel preparation (if appropriate) can help to minimise this risk. Advice about appropriate pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis is available (SIGN 2008). Specific issues are considered below.

Minimising the risk of chest infection

The risk of chest infection is increased in patients who receive a general anaesthetic or who have prolonged periods of immobility. Smokers, and patients with pre-existing respiratory disease, are also more likely to develop peri-operative respiratory problems such as pneumonia or bronchospasm (Warner 2006). Drugs and gases used in anaesthesia dry the respiratory tract and inhibit the action of the cilia. Secretions of mucus become thick and tenacious, causing partial obstruction of the lower airways. Cigarette smoking also damages and paralyses the cilia and leads to excess mucus production. The secretions eventually pool in the base of the lungs and plug the bronchioles. The retained secretions obstruct the lower airways, inhibiting gaseous exchange and providing a culture medium for bacteria.

General anaesthesia depresses respiration and, in the deep stage, breathing will actually cease. Artificial ventilation during the operation is at tidal volume and does not fully inflate the lungs (see Ch. 3). Normally, a person will sigh intermittently or increase demands for oxygen by activity, fully inflating the lungs and preventing stagnation and atelectasis. Changes of position, movement and coughing all serve to dislodge excess mucus or fluid, which is then expelled from the lungs as sputum. When under a general anaesthetic the patient will be lying still and unable to cough or sigh throughout the operation. There will also be a period of inactivity postoperatively and perhaps a reluctance to breathe deeply or cough if there is abdominal or thoracic pain. Opiates given for pain relief can also depress respiration (Baxter & Chinn 2006).

Current evidence suggests that patients should be advised to stop smoking prior to surgery (Warner 2006). Ideally patients should be encouraged to stop as soon as the surgery is scheduled because a longer period of pre-operative abstinence from smoking is associated with fewer respiratory complications (Warner 2006). This can also reduce other smoking-related problems such as peri-operative cardiovascular and wound-related complications. However, a study of 493 North American nurses (Houghton et al 2008) found that few regularly advised patients to quit or provided advice on doing so in the pre-operative assessment. While specialist smoking cessation services are available in the UK, all nurses should be able to offer support and advice to patients about stopping smoking. In fact, Houghton et al (2008) highlight that patients scheduled for a surgical procedure are more likely to stop smoking spontaneously than any other group in the general population. Advice about smoking cessation is available from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2005).

Reducing bacterial skin colonisation

The most significant cause of postoperative wound infection is the exposure to nosocomial pathogens, particularly Staphylococcus aureus (see Ch. 23). The risk can be reduced by shortening the length of hospital stay and the judicious use of standard infection control precautions by the nursing and medical team (Ch. 16).

Hair removal is considered by some clinicians, but shaving leaves small cuts and abrasions that harbour bacteria and may increase the risk of infection (Bockman & Putney 2008). Hair removal will only be necessary where sticking plaster is to be used, if the hair occludes the surgeon’s view of the operation site, or if adhesive ECG leads, requiring a good skin contact, are to be applied. Day surgery patients should be asked not to shave the operative site (Bockman & Putney 2008). If hair removal is necessary, then the use of electric hair clippers is associated with fewer breaches of the skin than shaving (Bockman & Putney 2008). Clippers should be sterilised (Hughes & Mardell 2009) and hair removal should be undertaken as close to the time of incision as possible. However, loose hair clippings could fall into the surgical field and increase the risk of infection, therefore this procedure should not be performed in the room where the operation is to be carried out (Bockman & Putney 2008).

Pre-operative showering may be helpful. Day surgery patients are usually recommended to shower and wash their hair at home prior to admission. This removes surface dirt and microbes (Scott et al 2007). Inpatients will be required to wash using hospital facilities. A single pre-operative shower is unlikely to reduce the risk of infection and Murkin (2009) suggests that patients undergoing open surgical procedures below the chin should be asked to have two showers with chlorhexidine gluconate solution in the pre-operative period, as this reduces the level of resident skin flora. Patients will usually change from their own clothing into a clean theatre gown. It is unnecessary to change clean bed linen.

The maintenance of peri-operative body temperature in the range 36–38°C has been associated with a reduction in postoperative wound infection (Bockman & Putney 2008). The use of warmed blankets or a forced air warming system can help maintain patients’ normal temperature (Bockman & Putney 2008). Moreover, a small study by Wagner et al (2006) found that patients reported feeling more comfortable and less anxious pre-operatively if they used a warming gown that allowed them to control their own temperature (Wagner et al 2006).

Bowel preparation

Prior to a procedure such as a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy effective bowel cleansing (bowel preparation) is important as it allows the endoscopist to accurately visualise the patient’s anatomy and identify abnormalities. Current techniques used to clean the bowel include administration of oral preparations such as sodium picosulfate (Picolax), a phosphate enema or glycerine suppositories. Since many of these procedures are undertaken as outpatient or day cases, the bowel preparation is sometimes carried out by the patient at home. Therefore, patients must find the techniques easy and acceptable to use. A randomised controlled trial by Darroch et al (2008) found that phosphate enemas were well tolerated and provided the best overall bowel preparation; however, glycerine suppositories were found to be difficult to self administer. Until recently it was thought that vigorous pre-operative cleansing of the bowel, together with the use of oral antibiotics, reduced the risk of septic complications after colorectal operations. Pre-operative bowel preparation is time-consuming and expensive, unpleasant for patients, and even dangerous on occasion because of the increased risk of perforation and inflammation. Analysis of the evidence, however, shows no benefit in terms of bowel leakage, mortality rates, peritonitis, need for re-operation, wound infection, or other non-abdominal complications (Guenaga et al 2009). Consequently, there is no evidence that mechanical bowel preparation improves the outcome for patients.

Minimising the risk of aspiration pneumonitis

In young and healthy individuals pulmonary aspiration is a rare complication of anaesthesia (Crenshaw & Winslow 2002). However, elderly patients, those who receive opioids and those with diabetes may have reduced gastric motility (Woodhouse 2006). Patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease are also more at risk of aspiration, particularly when in a prone position. Gastric emptying is usually complete for most meals in 4–5 h but even fasting patients may still have residual fluid in the stomach (Woodhouse 2006). Taking this into account, the recommended minimum pre-operative fasting period is 2 h for water and 6 h for food. This is the ‘2 and 6’ rule, and is summarised in Box 26.5 (RCN 2005).

Box 26.5 Information

While there is now a strong body of evidence and clear guidelines indicating acceptable minimum fasting times, research studies since the 1970s have consistently reported that pre-operative patients are often fasted for longer than necessary, with those on a morning list on average fasted for longer than those on the afternoon list (Jester & Williams 1999, Crenshaw & Winslow 2002). Prolonged fasting is associated with adverse effects (Crenshaw & Winslow 2002), mainly dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. The liver’s glycogen stores are sufficient to maintain blood sugar levels for approximately 18 h but even a fast of 6–8 h can reduce the body’s ability to cope with stressors such as blood loss or infection (Dean & Fawcett 2002). Older patients are particularly vulnerable to fasting. Depending on their pre-existing health status, older people are at risk of dehydration and confusion, potentially rendering them unfit for anaesthesia and surgery (Jester &Williams 1999). Fasting for patients with diabetes has additional risks, and maintenance of normal glucose levels may require a continuous dextrose/insulin infusion and regular checks of capillary blood glucose levels.

It is suggested that in order to cope with workload in a busy surgical unit, where theatre times are always approximate, nursing staff may not always adopt an individualised approach to fasting (Dean & Fawcett 2002, Woodhouse 2006). For example, all patients who are on the morning list may be instructed to fast from midnight regardless of their place on the list. This sets a wide margin of safety, with all patients fasting for at least 6 h. However, a patient on the morning list may be fasted from midnight but may not go to theatre until 11.00 h. Thus they may have fasted for at least 11 h. Nurse-led pre-admission and care pathways offer opportunities for this to be tailored more closely to the patient’s needs.

Minimising the risk of venous thromboembolic (VTE) events

DVT is usually diagnosed 3–14 days postoperatively (Dougherty & Lister 2008). The signs are swelling in the calf or thigh, and redness of the skin which typically becomes tight and shiny (Ingram 2003). Patients may complain of pain in the calf, particularly on dorsiflexion of the foot. However, up to 80% of DVT cases are asymptomatic (Ingram 2003). DVT is important because it can lead to pulmonary embolism (PE) and this carries a high mortality rate (Walker & Lamont 2007). Prevention of the development of DVT is an important nursing consideration and should begin in the pre-operative period.

Thrombus formation is initiated by the activation of factor XII in reaction to exposure to collagen filaments in the damaged endothelium. This results in platelet aggregation, formation of thrombin from circulating prothrombin, and stimulation of the production of insoluble fibrin from fibrinogen (see Ch. 11). It has been found that during surgery the veins of the lower leg distend. This distension leads to subluminal endothelial damage, which can provide a site for clot formation (Benkö et al 2001). In the soleal and gastrocnemius veins of the leg, the blood flow is highly dependent on exercise, and so these are often the sites of initial thrombus formation following prolonged periods of inactivity and lack of calf muscle pressure to assist venous return.

All surgical patients are exposed to a number of risk factors for DVT. However, this risk may be increased depending on the individual patient history and the procedure performed. During the pre-operative assessment, the nurse should assess the patient for the presence of known risk factors (Box 26.6).

Box 26.6 Information

(adapted from SIGN 2002, NICE 2007)

It is now generally accepted that all patients should use graduated elastic compression stockings (GECS) as these reduce the risk of developing DVT (Barker & Hollingsworth 2004). Although it is not fully understood how GECS work, these stockings create a decreasing pressure gradient in the leg from approximately 18 mmHg at the ankle to 8 mmHg at the thigh (full length) or to 14 mmHg at the calf (below-knee length). The gradient increases blood flow in the femoral vein, inhibits stasis of the venous circulation, stops build-up of any nidus of thrombosis formation and prevents the venous distension that causes endothelial damage (Parnaby 2004, Walker & Lamont 2007). GECS are inexpensive (Ingram 2003) and reduce the incidence of postoperative DVT by 50% (NICE 2007).

The role of the nurse is to ensure that a well-designed and well-fitting stocking is applied (Walker & Lamont 2007). Nurses should ensure that patients understand the importance of wearing GECS appropriately (Parnaby 2004). Stockings are fitted according to calf size and leg length and are available in a wide variety of sizes. If stockings roll down, a constricting band is created which may cause higher pressures, leading to an inverse gradient and delayed venous emptying. There are two lengths of stocking commonly available: thigh and knee length (Dougherty & Lister 2008). Thigh-length stockings are suggested to be more effective (SIGN 2002, NICE 2007) but below-knee stockings have been found to be more comfortable and compliance with therapy may therefore be better. They are also less costly than full-length stockings (Ingram 2003).

Inaccurately fitted stockings may offer no protection, or worse, lead to the development of ischaemic problems in the lower limb (Walker & Lamont 2007). Approximately 15–20% of patients are unable to wear GECS because of limb characteristics (Greerts et al 2001), marked leg oedema, severe peripheral arterial disease, dermatitis, severe peripheral neuropathy or other major leg deformity (SIGN 2002). The use of GECS is also contraindicated in patients with severe peripheral vascular disease or profound limb ulceration (Parnaby 2004, Walker & Lamont 2007). This emphasises the importance of accurate leg measurements and selection of the stockings. Nursing staff should also check the skin and circulation in the toes of any patient wearing GECS to detect complications, at least daily. If there are any concerns about correct fitting, the legs should be re-measured and new stockings applied. Patients should wear the stockings prior to surgery and up until discharge.

Intermittent pneumatic compression stockings (IPCS) are mechanical devices that fill with air, periodically compressing the calf and/or thigh muscles of the leg and stimulating fibrinolysis. For patients at high risk of developing DVT, such as those undergoing orthopaedic and cardiac surgery, intermittent pneumatic compression of the legs has been shown to be particularly effective (SIGN 2002), although Arnold (2002) suggests that patients are often reluctant to participate in this treatment postoperatively. Patients may remove stocking sleeves or disconnect the pump because they find the stockings hot or uncomfortable (Murakami et al 2003).

Teaching leg exercises and applying GECS and/or IPCS devices reduce the risk of DVT by their action on two aspects of Virchow’s triad: stasis and endothelial damage. Hypercoagulability can be avoided to some extent by adequate hydration but will be stimulated by the general adaptation to stress response and by the effects of surgery initiating clotting mechanisms. Medical staff will prescribe anticoagulants in the form of prophylactic low-dose heparin, often low molecular weight heparin, to minimise hypercoagulability. These anticoagulants are given daily or twice daily subcutaneously (NICE 2007). As full anticoagulation does not occur, the risk of increased intra-operative bleeding complications is minimal.

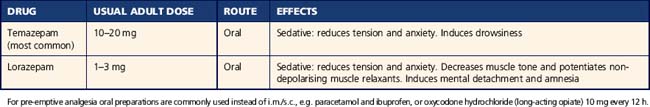

Premedication

The term ‘premedication’ (often abbreviated to ‘premed’) is used to describe drugs given to pre-operative patients before they leave the ward. These drugs constitute part of the anaesthetic and analgesia and are used to prepare the patient to receive a general or local anaesthetic (Table 26.1). They are often also used to relax the patient and relieve anxiety. However, research by Hyde et al (1998) found that, although often anxious about their surgery, many patients did not wish to be sedated in the immediate pre-operative period. Instead they would rather listen to music, read and be able to move about freely. The premed is prescribed by the anaesthetist after assessing the patient for the administration of the anaesthetic. The premed may be prescribed for a set time or ‘on call’, which means that the anaesthetist will telephone the ward to ask the nurse to administer the premed once it is clear how long it will take for the patient to be called to theatre. The nurse must ensure that the consent form has been signed, the patient has emptied their bladder and that all other pre-operative checks are complete before giving the premed. The patient should then be advised to rest and not get out of bed unsupervised if the premed contains a strong sedative or opioid. In day surgery premedication is not usually prescribed because it can make the patient too drowsy to be discharged home (Mitchell 2007a).

Theatre safety

The nurse must carry out pre-operative checks before the administration of the premed, as the results of the checks may necessitate a delay in going to theatre. Moreover, the patient should not have received sedative or opioid agents before signing the consent form. Many hospitals have created their own checklists. Examples of criteria for checklists are given in Table 26.2.

Table 26.2 Pre-operative checklist

| Criteria | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | Prepare two name bands with patient’s full name, hospital unit number, date of birth, home address (as a minimum), plus ward and consultant | Correct identification of patient |

| Clearly note allergies on the anaesthetic sheet and on wrist bands as well as the prescription chart | Avoidance of all allergens | |

| Ensure site is correctly marked with indelible ink | Correct identification of site | |

| Documentation | Ensure that medical notes, nursing notes, signed consent form, X-rays and anaesthetic sheet accompany patient to theatre | Ready availability of all necessary information |

| Fasting | Document when patient last had anything to eat or drink | Prevention of aspiration pneumonia |

| Empty bladder | Ask patient to pass urine prior to administering premedication | To prevent damage to full bladder during surgery |

| To enable complete bed rest after premed | ||

| To prevent postoperative discomfort due to a full bladder | ||

| Risk of diathermy burns | Ask patient to remove all jewellery, hair pins and other items containing metal (wedding rings may be covered with tape) | To remove all metal that may concentrate the diathermy current |

| Prostheses | Ask patient to remove all prostheses, e.g. dentures, hearing aids, contact lenses, false eyes, glasses, etc. | To prevent harm caused by prostheses To prevent loss |

| Care of valuables | Offer to receive valuables into safekeeping for the patient | Patient will be away from the ward and unfit to be responsible for these valuables |

| Circulatory assessment | Ask patient to remove all makeup, lipstick and nail varnish | To facilitate observation of colour of skin, lips and nail beds |

During the immediate pre-operative period, the patient may feel extremely vulnerable and anxious (Pearson et al 2004). They will be wearing only a flimsy gown, their dentures may have been removed, they may be unable to see well without glasses, and they may feel drowsy from the premed. Anxiety about the impending operation can be high, especially among patients placed in the later part of the operating list (Panda et al 1996). Reassurance by the nurse at this time and, for some patients, distraction, can be helpful. A family member or designated staff member offering support to the patient at this time may have a calming effect (Mayne & Bagaoisan 2009). Suggestions for managing this period in the day surgery setting are made by Mitchell (2007a).

Peri-operative safety

Caring for patients in the operating theatre

The anaesthetic or theatre nurse or ODA receiving the patient goes through the pre-operative check again (see Table 26.2) and, if possible, asks the patient to confirm details. The ward nurse will then usually return to the ward but if the patient is especially nervous or confused it can be comforting if a nurse or family member who knows them well can stay until the induction of anaesthesia (Mayne & Bagaoisan 2009). All patients must be supervised by a nurse in this pre-induction time, as the patient may have received premedication and is in an extremely stressful and unfamiliar environment. Many theatre nurses visit their patients pre-operatively to introduce themselves and also to give any information about patient care in theatre (Hughes 2002). In emergency cases, the theatre nurse may continue the pre-operative preparation.

The roles of theatre nursing staff are summarised in Box 26.7. Traditionally a surgeon is responsible for performing the surgery although Martin (2002) describes a nurse-led service in London where nurse practitioners perform minor surgical procedures using local anaesthetic. The anaesthetist will visit the patient pre-operatively in the ward to assess the patient’s ability to tolerate the anaesthetic, give information and reassurance, and prescribe a premedication if required.