CHAPTER 12 Nursing patients with skin disorders

Introduction

This chapter introduces dermatology nursing and the most common conditions encountered. Skin disorders range from minor conditions, resolved with over-the-counter (OTC) preparations, to potentially life-threatening skin conditions requiring intensive care and treatment (Skin failure p. 415). Many conditions are of a cyclical long-term nature with patients requiring care in different settings: inpatient, outpatient and community. Dermatology is a visual specialty and readers can access colour images in Further reading, e.g. Buxton 2003, the companion website and Useful websites.

Various research-based tools, e.g. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Finlay & Khan 1994) are used to investigate the quality of life (QoL) of patients with skin disorders and how skin disease impacts on their life.

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

The experience of skin disease may restrict social, professional and personal activities and impact on careers and relationships. Problems with sexuality and relationships can be linked to low self-esteem and the self-concept of an altered body image associated with having a skin condition (Marks 2003). The psychological morbidity of skin disease is often unrecognised by professionals (Lewis-Jones 1999) despite patients reporting their experiences of ostracism, stigmatisation and isolation – the ‘unclean leper’ status of having a skin disorder (Box 12.1).

Epidemiology of skin diseases

Skin disease is common. Approximately 20% of the UK population have a skin disorder meriting medical management. The type, incidence and prevalence of skin disorders depend on social, economic, geographical, racial and cultural factors (Gawkrodger 2008). Internal and external factors contribute to skin disorders (Table 12.1). The economic implications of skin disease can be considerable for individuals, families and employers. Skin diseases are the most common group of occupational health problems leading to absence from work. Work-induced dermatoses (skin disease) leads to lost working time and often to compensation claims.

Table 12.1 External and internal factors causing skin disease

| External | Internal |

|---|---|

| Ultraviolet light (UVL)/sunshine | Psychological factors/stress |

| Extremes of temperature – heat and cold | Genetic factors |

| Allergens | Systemic disease |

| Chemicals | Prescribed medications |

| Irritants | Herbal or over-the-counter products |

| Infections | Infections |

| Skin trauma/friction | Behavioural – scratching/picking |

Malignant melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is the second most common cancer in young adults (aged 15–34) (Cancer Research UK 2009a). It is largely preventable and may be curable if diagnosed and treated early (All Party Parliamentary Group [APPG] 2008). Non-melanoma skin cancer is also increasing with estimates suggesting doubling of rates every 10–20 years (APPG 2008). Current UK campaigns aim to change behaviour in relation to sunlight exposure and to UVL during sunbed use by educating people that a suntan is a sign of damaged skin rather than a desirable fashion statement. People should be alert for specific changes, a vital factor in early detection of melanoma.

Social factors impact on skin disorders, and improvements in standards of living, personal hygiene and nutrition have reduced the rate of certain skin disorders (Gawkrodger 2008). The current rise in the number of patients with asthma and eczema appears to be associated with environment changes of the home, e.g. central heating, carpeting, etc. Unemployment and low wages restrict job mobility and people with industrial skin diseases may have difficulty in changing jobs to alleviate the condition. Homelessness and poor housing create problems in maintaining skin care, the former often resulting in limited access to medical care.

The nurse’s role

Patients with skin disorders and support groups have asserted their right to access specialist staff and be nursed in specialist areas (Department of Health [DH] 2004). If nurses can spend time talking with the patient, educating and demonstrating skin care techniques, it increases their confidence and potentially the patient becomes the ‘expert’ and the burden of skin care can be alleviated by supported self management (Dermatology Workforce Group 2007), a strategy that fits with Government position on long-term conditions (DH 2006).

Cure is not a word widely used in dermatology given the cyclical nature of many conditions, so nurses involved often forge long-term relationships with patients. Nurses with experience of chronic skin disease can help patients who require empathy and guidance from specialist practitioners who have the time, knowledge and willingness to share clinical skills with this motivated client group. Kurwa & Finlay (1995) reported inpatient management as improving QoL for dermatology patients, while peer group interaction between patients in dermatology wards is recognised as beneficial.

It is important to share this specialist knowledge with primary care nurses as ‘care moves closer to the patient’ with dermatology being one of the specialisms moving into the community from secondary care (DH 2006). The supportive role of nurses in primary care is vital. Only a small minority of patients are referred to dermatologists. Self-medication, OTC therapies and nurse prescribing mean that, for many, pharmacists and community teams are the first contact for most patients. The dermatology nurse specialist/practitioner/liaison uses educational input to support the primary care team in providing information and therapies that are valid, accurate and up-to-date and, in an advisory and consultative capacity, helps sustain continuity of care (Stone 1997). Dermatology nurse practitioners/specialists have introduced initiatives in many areas of practice such as nurse-led clinics for chronic disease management (eczema, psoriasis, acne) utilising non-medical prescribing and managing patients with skin cancer. Nurses are therefore an important group within the dermatology team, playing a vital role in the provision of direct specialised care.

Anatomy and physiology

Structure of the skin

Epidermis

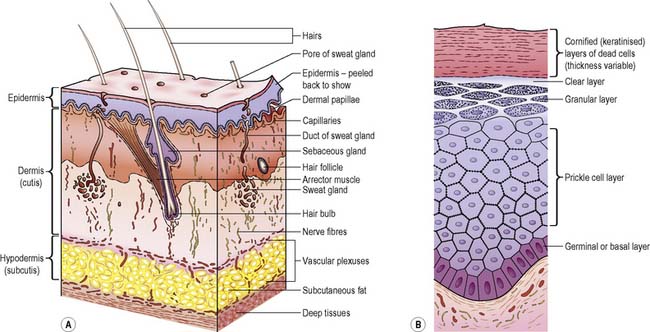

The epidermis is composed of stratified epithelium and varies in thickness between different parts of the body; skin on the palms and soles is thicker than that on the face or back. The epidermis is avascular, the cells being nourished by means of diffusion of materials. Structures passing through the epidermis include hair follicles and sebaceous and sweat glands (Figure 12.1A). The epidermis has several layers, its health depending on three factors:

The layers of the epidermis are (Figure 12.1B):

Functions of the skin

Intact skin is vital to health and well-being. As the largest organ in the body, weighing approximately 4 kg, and having a surface area of 2 m2, the skin has many vital functions (Hughes 2001):

Vitamin D synthesis

Epidermal cells produce 7-dehydrocholesterol, which is slowly converted to vitamin D when skin is exposed to UVL (see Chs 10, 21).

Temperature regulation

The skin is vital in temperature regulation (see Ch. 22). In cold conditions heat is conserved by vasoconstriction and generated by the involuntary muscular action of shivering. Body hair becomes erect to trap warm air on the skin. During overheating, sweating is induced and vasodilatation occurs. As sweat evaporates from the skin, latent heat is lost from the skin surface, causing it to cool. Vasodilatation allows large quantities of blood to circulate in the uppermost layers of the dermis. Heat is then lost through convection, radiation and conduction. Blood flow is controlled to direct blood either to the capillary bed closer to the skin surface (maximum heat loss) or to the deeper tissues of the skin (minimising heat loss).

Skin assessment

Physical examination

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

During assessment, the nurse should recognise that skin changes can be a manifestation of systemic disorders, e.g. liver disease. Peters (2001) reminds the nurse to recognise the wide diversity of skin colour and pigmentation in society. The pathophysiology of the disorder will be unchanged, but skin pigmentation can influence skin changes during illness.

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

The nurse should also recognise that the effect of the physical appearance of a skin disorder on quality of life is often viewed by the patient as being of greater importance than the discomfort of having abnormal skin (Lewis-Jones 1999).

Principles of therapy in skin disorders

Topical therapies

Topical therapies are usually known as first-line treatments and are applied directly on the skin which is the target organ and readily accessible. Various classes of topical preparations are used (Box 12.2).

Box 12.2 Information

Ongoing commitment is needed to maintain treatment as topical therapies can be messy, time-consuming and smelly (Box 12.3). Treatment programmes often have to be customised because therapeutic responses can differ with each patient.

A fire hazard is associated with the use of paraffin-based skin products (National Patient Safety Agency 2007) and nurses must alert patients to this danger.

Emollients

Patients may use a combination of emollients for different areas of the body. Taking time to demonstrate application technique and trial different moisturisers so the patient is involved in choice (Peters et al 2008) is key to compliance. For further information see Ersser et al (2007) and Useful websites, e.g. Dermatology UK.

Topical corticosteroids

The potential side-effects, such as skin thinning, bruising/purpura, hirsutism, systemic effects, etc., depend on the age, site and frequency of the product used. A recent review stated that ‘the intermittent use of topical corticosteroids is highly effective; bears little risk, and is relatively inexpensive’ (Hengge et al 2006, p. 12).

A concern with children is that they are more prone to the development of systemic reactions based on their higher ratio of total body surface area to body weight. Epidermal thinning does occur within 1–3 weeks of treatment with potent or very potent topical steroids on normal skin but reverses within 4 weeks of stopping (O’Donoghue 2005). It is now recognised that emollient therapy is potentially steroid sparing (Grimalt et al 2007) and this potentially corrects the defect in the skin barrier, so using emollient therapy for washing, bathing and as a leave-on preparation is key to the day to day management with intermittent use of topical corticosteroids.

Other topical therapies

Other topical therapies used include:

Each therapy has to be applied in a different manner and nurses advising the patient must know the difference and the potential effect it has on the skin in order to advise the patient. See Useful websites, e.g. British Dermatological Nursing Group (BDNG).

Systemic therapies

A range of oral medication, from antibiotics to immunosuppressant to biological drugs, is used to treat long-term inflammatory conditions as well as acute inflammatory or bullous conditions. Monitoring of patients on oral medication is often undertaken by dermatology nurses who work as non-medical prescribers: they interpret blood results and alter doses or initiate alternative therapies used in conjunction with topical therapies (see Useful websites, e.g. The British Association of Dermatologists). Nurses must know the potential side-effects of topical and systemic therapies in order to provide safe care and when necessary be able to adjust therapy accordingly.

Disorders of the skin

Psoriasis

Precipitating/aggravating factors include:

Psoriasis varies from mild forms, with plaques localised to the knees and elbows, to severe forms which are potentially life threatening. Classification of psoriasis is made on clinical presentation or location (Weller et al 2008).

Plaque

presents as well-demarcated, erythematous plaques covered in dry, white waxy scale often localised to the knees and elbows (Figure 12.2). Plaques vary in size and extend to cover the trunk and scalp. Plaque psoriasis tends to be chronic, with exacerbations and periods of remission.

Pustular

is a localised form affecting the hands and feet. It is characterised by yellow/brown pustules which dry into brown scaly macules (Figure 12.3). It is a painful condition, difficult to treat and linked to smoking and very debilitating.

Psoriatic arthropathy

is a rheumatoid-like arthritis affecting about 5% of psoriatic patients. Joint changes occur in hands, feet, spine and sacroiliac joints. This arthropathy mimics rheumatoid disease but notably the rheumatoid factor test is negative (see Ch. 10). Psoriatic arthropathy is difficult to treat, meriting the combined expertise of a rheumatologist and a dermatologist.

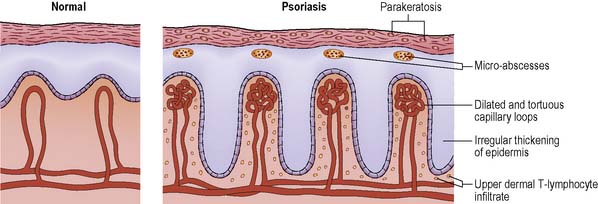

Pathophysiology

The epidermis thickens, with an associated increased blood flow to the skin, and becomes raised to accommodate skin changes (parakeratosis) (Figure 12.4). Epidermal cell proliferation rate increases. The transit time of epidermal cells maturing through normal skin is approximately 21–28 days, whereas in psoriasis it is 4 days. The increased cell production and transit time mean that cells do not keratinise completely and so cannot be shed. This causes the build-up of a white, waxy silver scale as immature skin cells remain adherent to the skin. Psoriasis results from an increase in activity of dividing cells associated with an increase in their rate of reproduction. The cause is not fully understood but is interlinked with the immune system.

Common presenting signs/symptoms

Medical management

Investigations

Diagnosis can be made from the clinical picture and relevant history:

Treatment

This may involve topical and systemic medication and phototherapy. PUVA and UVB are effective therapies for psoriasis (see p. 402). The combination of therapies chosen depends on diagnosis and severity of the disorder, topical prescribed therapies being the mainstay of psoriasis treatment (see Nursing management and health promotion section pp. 405–406).

Medication

The majority of patients with psoriasis respond to topical therapies, but the more extensive forms of psoriasis may require a systemic approach (Weller et al 2008). Medications that are particularly important in this regard are methotrexate, ciclosporin, retinoids (e.g. acitretin) and biologics (e.g. etanercept).

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

Nursing management and health promotion: psoriasis

The goals of nursing management will vary depending on the type and severity of the person’s psoriasis. If the epidermal barrier is breached as in severe erythroderma leading to acute skin failure, measures are needed to support the epidermal barrier (see Skin failure, p. 415). Generalised pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis can be life-threatening conditions requiring skilled nursing.

![]() See website Critical thinking question 12.1

See website Critical thinking question 12.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree