CHAPTER 10 Nursing patients with musculoskeletal disorders

Anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal system

This section gives a brief overview of the anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal system (see Further reading, e.g. Marieb & Hoehn 2007).

The skeletal system

The skeletal system consists of bones and the joints where they articulate and move.

The main functions of the skeleton are:

Structurally, the skeletal system consists of two types of connective tissue: bone and cartilage.

Cartilage

There are three types of cartilage:

The axial skeletal system

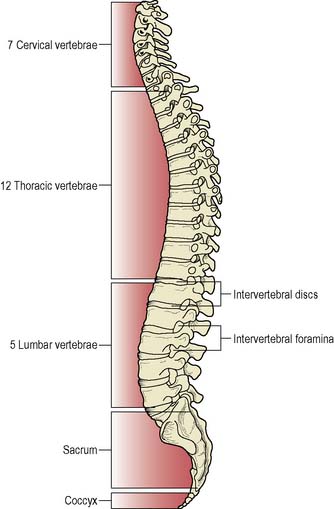

The skull, vertebral (spinal) column and the sternum/ribcage form the central axis of the skeletal system. The spinal column is a strong, flexible column of 33/34 bones, 24 of which are ‘true’ vertebrae – the 7 cervical (C), 12 thoracic (T) and 5 lumbar (L) vertebrae – the remainder being 9/10 fused bones that form the sacrum (S) and coccyx (C) (Figure 10.1). Between each of the vertebrae from C2 to S1is a strong joint created by the fibrocartilaginous intervertebral discs, which allow flexibility and act as shock absorbers when the spine is exposed to vertical forces.

The appendicular skeletal system

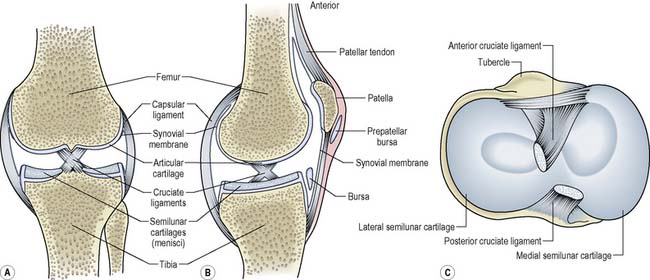

The bones of the upper and lower limbs and their girdles (the upper pectoral girdle and the lower pelvic girdle) are the main parts of the appendicular skeletal system. They are characterised by the presence of synovial joints which connect the articular surfaces of adjoining bones (Figure 10.2). The bones that make up the joint are held within a fibrous capsule, which consists of two layers:

The articular surfaces of the bones involved are covered in hyaline cartilage – articular cartilage.

Ligaments

Ligaments attach bone to bone and are vital in maintaining the stability of a joint. They are made of dense connective tissue and have a relatively poor blood supply. A joint may have many ligaments, such as the knee which has the cruciate ligaments to prevent the femur and tibia moving forwards on each other and the medial and lateral collateral ligaments which prevent side to side movement (Figure 10.2). Damage to ligaments can result in an unstable and painful joint, common in football injuries.

The muscular system

Nursing assessment

This will involve a holistic assessment of the patient, as musculoskeletal disorders can have profound effects on a patient physically, psychologically and socially. In addition, visual inspection, palpation, measurement, and other investigations such as radiological/imaging studies (Box 10.1) and blood tests in rheumatoid arthritis, for example, are necessary.

Box 10.1 Information

Investigations for musculoskeletal abnormalities

Radiological and imaging studies

Joint examination

In particular the nurse should assess for:

Problems and strengths (actual and potential) are identified in the following categories:

Nursing interventions

Nursing management and health promotion: core potential complications

Compartment syndrome (CS)

Compartments within the body are areas where muscle, nerve and blood vessels are confined within inelastic boundaries of skin, fascia and/or bone. Compartment syndrome occurs when there is increased tissue pressure resulting in compromised circulation and function of tissues within a compartment (Lucas & Davis 2004). This results in tissue death (necrosis) and permanent loss of function, which can occur within 6–8 h. Increased pressure can result from direct trauma to the area, surgery or the application of a cast or other immobilisation aid. Nursing observations include examination of the colour, warmth, sensation and movement (CWSM) of the foot or hand distal to the injury, surgery site or constricting device such as a cast. The ‘5 Ps’ that should be looked for are:

In order to reduce the risk of CS developing the affected limb should be elevated, unless CS is suspected to have occurred, when elevation can exacerbate the condition and should be stopped (Lucas & Davis 2004). Compartment syndrome is an orthopaedic emergency and patients need to have surgery to relieve the pressure – a fasciotomy where the inelastic tissue surrounding the compartment is cut open.

Venous thromboembolism

It is usually a combination of these factors that causes a DVT. The result is a clot in the deep veins (of the leg or pelvis), most commonly of the lower leg. Signs and symptoms may include pain/tenderness, calf pain when the foot is dorsiflexed, redness, heat, swelling and hardness of the affected areas. Sometimes, however, there are no physical signs. Nursing management and health promotion includes educating vulnerable patients about the signs and symptoms so that they can inform staff if they occur, and the use of preventative measures to reduce the risk (see Ch. 26). These measures may be pharmacological, for example low molecular weight heparin injections, or non-pharmacological such as properly fitted antiembolism stockings, foot impulse device and early mobilisation (National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care 2007).

A DVT which breaks off and travels through the heart to the pulmonary circulation is known as a PE. This is an emergency as it can lead to respiratory arrest and death. The clinical presentation depends on severity but includes sudden sharp chest pain, tachycardia, dyspnoea, cough, cyanosis, fainting, sometimes haemoptysis, and restlessness/confusion in previously orientated patients. There will also be characteristic electrocardiogram changes. (See Further reading, e.g. Farley et al 2009, for details of PE.)

Skeletal disorders

Fractures

A fracture or ‘broken bone’ is a break in the continuity of a bone (Langstaff 2000) as a result of direct or indirect trauma, underlying disease (pathological fracture) or repeated stress on a bone (stress fracture). It is described as a closed fracture when there is no communication between the external environment and the fracture site, and open when communication occurs. Stable fractures are those where the bone ends are lying in a position from which they are unlikely to move. In unstable fractures the bone ends are displaced or have the potential to be displaced. The edges of the broken bones may damage soft tissues or blood vessels/nerves at the time of the injury or later through poor handling of the limb.

Medical/surgical management

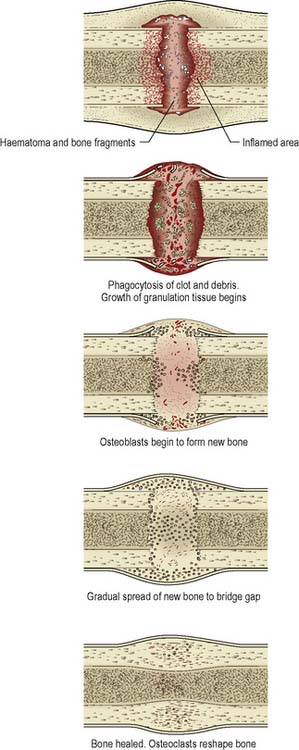

All fractures, regardless of their position or the size of the bone involved, are managed according to three principles: reduction, maintenance of position and rehabilitation. The aim is to allow bone healing to take place. The stages of bone healing are demonstrated in Figure 10.3.

Traction

Orthopaedic traction occurs when a pulling force is applied to a part or parts of the body, and counter-traction, a pulling force in the opposite direction, is also applied (Lucas & Davis 2004). Counter-traction is usually supplied by the body weight of the patient. It is used in the following circumstances:

Types of traction

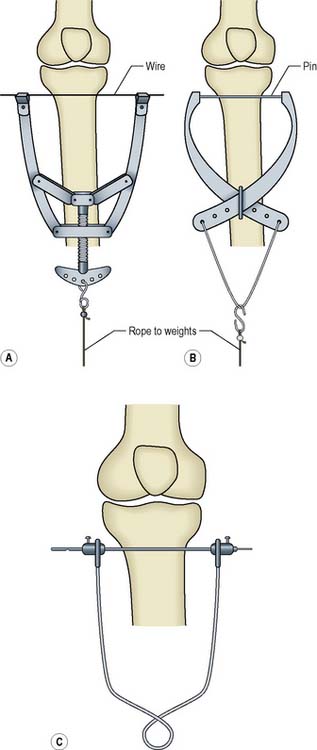

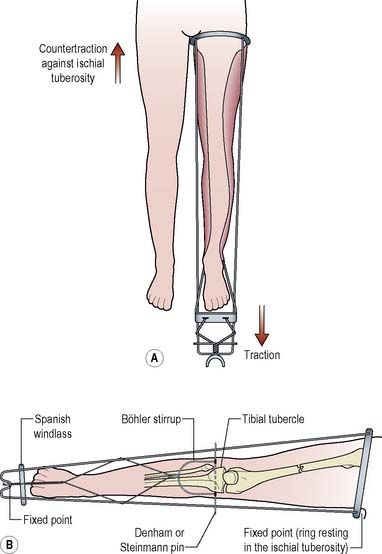

Balanced or sliding traction

This relies on the patient’s own body weight to produce the necessary counter-traction, usually by tilting of the bed. Skeletal pins may be used to provide a firm point of attachment (Figure 10.4), but the most common type of balanced traction uses skin traction. This is Buck’s traction which is used as a temporary measure for pain relief in patients with a fractured neck of femur (Figure 10.5). However, a Cochrane Review (Parker & Handoll 2006) could find no evidence which conclusively demonstrated the benefit of such traction for the outcome measures of pain relief or ease of fracture reduction at the time of surgery and its use has been discontinued in many orthopaedic centres.

Fixed traction

This is the application of counter-traction acting through an appliance which obtains purchase on a part of the body (Figure 10.6). The most common is a Thomas’ splint, used for restricting movement of a fractured shaft of femur when transferring a patient, e.g. between hospitals, or in the treatment of fractures of the shaft of femur in children (Lucas & Davis 2004).

Nursing management and health promotion: traction

In addition to the general principles outlined earlier for management of musculoskeletal disorders (p. 339), the following are specific to a patient in traction.

Health promotion

Patients need to understand the reasons for their traction and how to move safely within the bed.

Reducing the risk of complications

Care of skeletal pin sites

A Cochrane Review (Lethaby et al 2008) concluded that there is little evidence as to which pin site care regimen best reduces infection rates but there are best practice guidelines available based on the available literature and expert opinion (Lee-Smith et al 2001). These indicate that:

Purulent discharge, redness or inflammation suggests infection and a wound swab should be taken to identify the causative organisms. The appropriate antibiotics should be commenced and the pin sites cleaned with 0.9% saline and dressed with woven gauze, changed as necessary (Lee-Smith et al 2001).

Casts

A cast is a splinting device comprising layers of bandages impregnated with POP, fibreglass or resin, some of which are applied wet and solidify as they dry out. Their main uses areto immobilise and hold bone fragments in reduction and to support and stabilise weak joints. POP moulds more easily but it takes 48 h to dry and it is heavy. Synthetic casts set within 20 min and allow early weight-bearing but do not accommodate swelling and are not usually used in the initial stages of treatment, when a POP backslab is used. Other types of casts include adjustable focused rigidity primary casts which can be adjusted as swelling reduces (Large 2001) and cast braces which have hinges at the joints to allow restricted amounts of flexion or bend to stimulate cartilage nutrition (Dandy & Edwards 2009).

Nursing management and health promotion: casts

In addition to the general principles of nursing management for musculoskeletal disorders (p. 339), the following will also apply.

Care of the cast

Many patients will go home wearing casts and need clear verbal and written instructions specific to their cast (Box 10.3 outlines advice for a patient with a hand to elbow plaster).

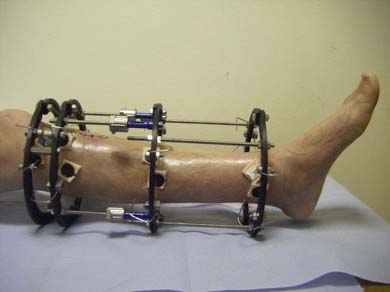

External fixation

Bone fragments are held in position by skeletal pins inserted into the bone on either side of the fracture and held in alignment by a scaffold or a ring fixator (Figure 10.7). They are used for the treatment of some closed fractures, e.g. the pelvis, to stabilise open fractures with extensive soft tissue loss until the soft tissue has healed, for fractures that have not united by other methods, and for reconstructive surgery such as leg lengthening. Depending on the reason for their use they can be in place for as little as 6 weeks, e.g. for treatment of a closed fracture, or up to 1 year, e.g. in non-union of a tibial fracture.

Figure 10.7 An example of external fixation – Ilizarov frame.

(Courtesy of Barts and the London NHS Trust.)

Nursing management and health promotion: external fixation

The general principles relating to potential neurovascular impairment, positioning and potential for pin site infection that have already been discussed are important in the care of patients with an external fixator. In addition it is important that the patient, carers and community staff are confident in caring for the external fixator when the patient is discharged from hospital, including managing issues related to altered body image (Limb 2004). (See Further reading, e.g. Dandy & Edwards 2009.)

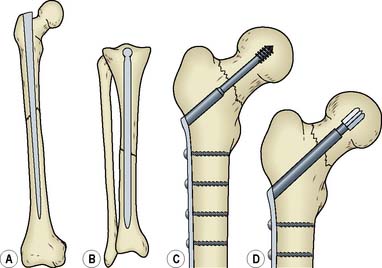

Internal fixation

Fractures may also be stabilised by surgical intervention where nails, plates, wires, screws or rods hold the bone fragments in place (Figure 10.8). Again this permits earlier mobilisation and reduces the potential for complications. The general principles of nursing management and health promotion of musculoskeletal disorders and of core potential complications (pp. 339–341) apply. In addition the perioperative principles of nursing management are also relevant (see Ch. 26).

Fractures of specific sites – lower limb

Fracture of neck of femur

There are approximately 70 000 fractures of the femoral neck, commonly known as a hip fracture or fractured neck of femur (and abbreviated as #NOF), in the UK each year (British Orthopaedic Association [BOA] 2007). They are most common in older people, particularly women who may have osteoporosis. There is much evidence that a coordinated approach to care of this patient group can improve patient outcomes (Box 10.4).

Box 10.4 Evidence-based practice

Hip fracture: the care of patients with fragility fracture: the ‘Blue Book’ guidelines

(The British Orthopaedic Association, 2007.)

Medical/surgical management

Treatment

Depending on the site of the fracture, and the age and condition of the patient, the treatment will be either internal fixation with a plate and screws or replacement of the head of femur with a metal prosthesis if the fracture is inside the joint capsule and there is a risk of damage to the blood supply of the femoral head (Figure 10.9). The underlying osteoporosis needs to be treated (see p. 351).

Figure 10.9 Blood supply of the femoral head via the capsule, intramedullary vessels and ligamentum teres.

Nursing management and health promotion: fracture of neck of femur

Potential complications

As a result of age and general physical condition when found, the patient may be confused and fearful and need a great deal of comfort and reassurance. Measureswill be taken to reverse any hypothermia and dehydration (see Chs 20, 22). Risk assessment of the patient for skin breakdown using an approved scale such as the Waterlow scale (see Ch. 23) should be recorded and the patient may be nursed on a therapeutic bed. Vital signs will be monitored at least 4-hourly intervals to detect early signs of complications.

Pain

With an extracapsular fracture there is often extensive bruising which adds to the severe pain. Pain assessment and pain relief measures should be implemented (see Ch. 19) including repositioning and supporting the limb, and administering prescribed analgesics.

Increased risk of multisystem complications

For an older patient, such acute trauma and associated surgery may lead to multisystem failure (see Ch. 18).

Rehabilitation

Discharge planning should commence within 48 h of admission (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] 2002). The use of an integrated care pathway (ICP) can help to improve the standard of overall care by ensuring that each member of the multidisciplinary team knows the best available evidence for care and when that care should be carried out (Tarling et al 2002) (Table 10.1, Box 10.5). Early supported discharge schemes, often led by nurses, can help to ensure that patients are discharged rapidly but safely to their home environment (British Orthopaedic Association 2007).

Table 10.1 Extract from the integrated care pathway of a patient with a fractured neck of femur – postoperative day 1 (nursing part only)

| Patient Problem/Need | Nursing Intervention | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Recovery from anaesthetic | At least 4-hourly monitoring of vital signs | Vital signs within patient’s normal limits |

| Wound care | Check wound site dressing Check and record wound drainage | Dressing dry and intact Drain to be removed at 24 h after surgery as further drainage minimal |

| Neurovascular status of limb | Monitor neurovascular status of affected limb | No neurovascular deficit |

| Relief of pain | Use pain score with patient at least 4-hourly Administer analgesics as prescribed | Pain relief at level acceptable to patient |

| Risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | Ensure antiembolism stocking in situ Thromboprophylaxis injection as prescribed Monitor for signs of DVT | Reduction in risk and early detection of problem |

| Reduced mobility | Ensure patient understands correct way to transfer and mobilise | Patient to sit in chair Patient to walk to end of bed with aid of Zimmer frame |

Fracture of the tibia and fibula