CHAPTER 15 Nursing patients with disorders of the mouth

Introduction

Nurses remain the ‘key personnel’ in the multidisciplinary team (MDT) in the early detection of oral symptoms and potential problems patients may encounter with performing oral hygiene procedures (Murphy 2005). However, McGuire (2002) notes that: ‘…there are a number of barriers that prevent patients from receiving needed care. These barriers range from a lack of knowledge, to inconsistent practice, to administrative and environmental issues’ and oral care remains an often neglected aspect of nursing care. It has been recognised that many nurses feel uncomfortable about raising the topic of oral hygiene with their patients, and may consider an oral examination to be an ‘infringement of patients’ integrity’ (Murphy 2005). Miller & Kearney (2001, p. 241) suggest that ‘mouth care has become a ritualistic and banal activity, a topic of conflicting advice and subjective conclusions from sporadic research’. McAuliffe (2007) reports similar experiences, adding that oral hygiene practice is also carried out ‘without reference to patients’ individual needs’, and is a task delegated to junior nurses or auxiliary staff, who may have received little educational preparation. Mouth care should not be regarded as a standard procedure, but must be adapted to meet the needs of individuals in various care settings throughout life, and at various points on the health–illness continuum.

Oral diseases are generally not given priority over other complex medical problems despite the often profound effects of oral problems on a person’s quality of life (Doyle & Dalton 2008). The mouth is often the first indicator of generalised systemic disease or disease in adjacent structures and its immediate visibility gives any dysfunction a particular significance for the individual, who may be acutely aware of any disfigurement (cosmetic or functional). This can give rise to many difficulties affecting the person’s self-perception and quality of life.

Anatomy and physiology

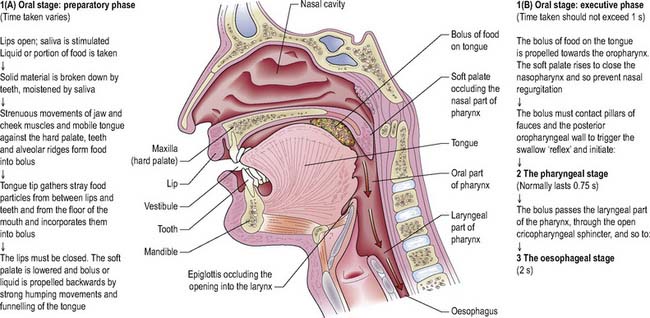

The oral cavity has evolved as a ‘workshop’, where much activity associated with chewing (mastication), drinking and speaking takes place (Figure 15.1):

Saliva

This is formed by a combination of secretions from the parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands and from the numerous minor glands in the mucous membrane. Saliva plays an essential role in lubrication and protection of the oral mucous membranes (Xavier 2000), and salivary amylase is the enzyme that begins starch digestion whilst the food is still in the mouth. For more information about the physiology of salivation, see Holmes (1998).

Disorders of the mouth

Disorders of the mouth can be broadly classified into five categories:

Congenital orofacial deformity

Problems associated with such facial deformities may include:

Cleft lip and palate

A cleft lip and palate is a congenital deformity in the body’s natural structure caused by an embryonic developmental failure 6–12 weeks after conception. Cleft lip may be unilateral or bilateral and can vary in severity from a slight notch to complete division of lip and gum which presents the child with significant functional and aesthetic implications (Zuk 2008). Cleft palate can result in inability of the soft palate to meet the posterior pharyngeal wall and close off the nasopharynx. If uncorrected, speech is affected, producing a typically ‘nasal’ delivery in which certain consonants, particularly C, D, K, P, S and T, cannot be properly enunciated. For further information on rarer deformities of the mouth and face, see Wray et al (2003).

Medical management

Treatment

The medical management of oral defects requires a multidisciplinary approach extending from infancy to adulthood. Treatment protocol will depend on the extent of the deformity and the age of the child, but typically the patient will endure numerous procedures over the course of at least a decade. The aim of cleft surgery is timely reconstruction of the functional units that have been disrupted by the cleft (lip/nose and palate), so that normal facial development can be achieved (Oxley 2001). For management of cleft lip/palate, see Zuk (2008) and Table 15.1.

Table 15.1 Treatment of cleft lip and palate

| Procedure | Timing/Patient’s Age |

|---|---|

| Lip repair | 0–6 months |

| Palate repair | 4–24 months |

| Bone graft to alveolus | 9–11 years |

| Osteotomy (for correction of defect of hard palate) Rhinoplasty (for nasal defect) | Around 18 years |

| Pharyngoplasty (to correct the pharynx) Myringotomy revision procedures | As and when necessary |

| Orthodontic treatment | Throughout childhood and into adulthood |

| Speech therapy | As and when necessary |

Nursing considerations

Although deformities may be discovered by prenatal screening, the experience for parents of such a newborn child may be very traumatic, and the provision of sensitive and supportive counselling is vital. The way in which nurses care for and support the parents can aid their adjustment to the situation (Hodgkinson et al 2005). Parents should be given a clear and accurate account of the expected management plan for their baby at the earliest opportunity (Filies et al 2007).

The currently accepted model of care for the management of patients with a cleft lip/plate is a multidisciplinary team approach and they should be referred to the relevant professionals, e.g. specialist nurse, orofacial consultant, orthodontist, speech therapist, genetic specialist. With the increase in antenatal diagnosis, contact with the specialist team often happens before the birth. Information on local support groups or other appropriate self-help groups should also be provided. Professional psychological support may also be required and it is recommended that the team should include a mental health professional (De Sousa 2008).

Oral health and orodental disease

Dental and periodontal disease (Figure 15.3) continue to pose an important public health problem (Jones et al 2005), affecting about 95% of the population of the UK in varying degrees and accounting for the largest proportion of mouth disorders. Although loss of teeth is not a lethal disease, the burden of oral disease in terms of financial, social and personal impacts is considerable (Kwan et al 2005).

Changing patterns of dental health

From the early 1970s, there was a substantial improvement in dental health in the UK. More people retained their natural teeth into later life, and there was a marked decrease in dental caries in children. Dental caries, also known as tooth decay, is a disease where bacterial processes dissolve the tooth structure, causing the progressive breakdown of the hard structures of the tooth, and producing holes (cavities) in the teeth. By 1998, dentate adults had fewer missing teeth and greater numbers of sound, untreated teeth on average than in 1978. However, improvement in children’s dental health appears to be reversing and there was no improvement in 2001/2002 compared to the two previous years. Furthermore, the 2003 Children’s Dental Health Survey reported that since the previous survey in 1993, the proportion of children with plaque and gum disease had risen in 5, 8, 12 and 15 year olds (White & Lader 2004). In the UK, 40% of children have dental decay (Morgan et al 2008), but there is wide regional variation. Most epidemiological studies conclude a direct correlation between socioeconomic status and periodontal disease (Peterson & Ogawa 2005). The most recent survey into children’s dental health in the UK (Lader et al 2005) confirmed this relationship, with the average number of teeth showing obvious decay being lower among children from professional and managerial backgrounds compared with those from routine and manual families. There are serious implications for health in later years if dental disease remains untreated in childhood.

Promoting oral health

As illustrated by Box 15.1, nurses in all spheres of practice can help with early education in the simple preventative measures that are key to oral health.

Box 15.1 Information

Contribution of nurses and midwives to orodental health

Nurses working with those with learning disability

Supervise early and continued dental care and thus minimise need for restorative dentistry.

A nurse-led initiative described by Black (2000) is aimed at educating children and their parents to improve their diet and dental health, and to identify orodental problems early. Such health promotion messages can be reinforced throughout the most influential stages of children’s lives, enabling them to develop lifelong sustainable attitudes and skills (Kwan et al 2005).

Oral hygiene

Toothpaste

with added fluoride is recommended, except in areas with fluoridated water, as the adverse effects of fluoride (see below) depend on total fluoride dosage from all sources. Current advice is that it is unnecessary to rinse, thus leaving a film of fluoride toothpaste. It should be emphasised that ‘topical’ fluorides such as toothpaste can have a ‘systemic’ effect when they are inadvertently ingested by young children. Studies have shown that 47–72% of dental fluorosis in children can be attributed to the systemic effect of fluoride toothpaste (Jones et al 2005). Ingestion of fluoride before 3–4 years (i.e. pre-eruptive fluoride exposure) is critical to the probability of fluorosis, as this is when the formation of the permanent teeth occurs.

Fluoride

is a substance naturally present in water in some areas. It is taken up by growing teeth and makes enamel harder and more resistant to the development of caries. There is strong evidence that the incidence of caries is considerably reduced in areas of naturally occurring fluoridated water (Stephen et al 2002). However, much controversy surrounds water fluoridation (Cross & Carton 2003). Excessive intake of fluoride, either through fluoride in the water supply, naturally occurring or added to it, or through other sources, causes fluorosis. This can appear as faint white ‘mottling’; but in its severe form it is characterised by black and brown stains and pitting of the teeth. This pitting and loss of enamel in the more severe form of fluorosis increases the risk of dental caries (Levy 2003).

Diet

There is a direct correlation between the incidence of dental caries and availability of sucrose, with poor diet predisposing to dental decay in children. Children are particularly vulnerable to sophisticated TV advertising promoting high fat, sugar and salt containing foods, such as confectionery (Morgan et al 2008). Nurses can contribute to health education in this area, and emphasise the damaging effects of non-milk sugars, which include fruit juices, honey and sugar, especially when consumed by young children last thing at night.

Access to dental care

The dental surgery is often the first remembered clinical setting for health care. If these first visits are pleasant, a positive attitude may be created towards future regular dental check-ups, and subsequent disease can then be diagnosed early. In the adult population with learning difficulties, changes from institutional living to community-based housing may be associated with reduction in dental attendance and treatment (Stanfield et al 2003). Older housebound people face similar problems.

The future dental health of the nation may be affected by factors including regional variation in accessibility of NHS dentistry, increased treatment charges and changes in funding of dental services. Although 75% of British adults consider oral health to be important to quality of life (McGrath & Bedi 2002), only 59% of adults were likely to attend for regular dental check-ups, and younger adults (16–24 years) were less likely to do so than when they were 5 years younger (Nuttall et al 2001).

Dental and periodontal disease

Pathophysiology

Calculus (tartar)

is hard mineralised plaque which requires removal by a dental surgeon or dental hygienist.

Periodontitis

is characterised by gradual loss of the supporting periodontal membrane of the teeth and erosion of supporting alveolar bone (Figure 15.4). Once the periodontal membrane and bone have been destroyed they cannot be replaced and subsequent loosening of teeth occurs.

Medical management

Inpatient or day-case procedures

Patients taking certain types of medication and those with the following medical conditions may require hospital treatment (Wray et al 2003):

Nursing considerations

Outpatient care

Individuals treated in dental surgeries or as hospital outpatients will require reassurance and advice on aftercare at home (Box 15.2).

Box 15.2 Information

Information for patients having minor oral surgery

On the day of treatment

Promoting oral health and comfort in special client groups

Physically disadvantaged and those with learning difficulties

Individuals with limited motor control or manual dexterity may require help with brushing teeth. Toothbrushes with adapted handles are available to aid gripping and the nurse should be aware of how these can be obtained (often from an occupational therapist). Electric toothbrushes often make tooth brushing more effective and easier to perform. Many people with limited movement depend on the mouth and teeth to hold or control equipment; it is thus especially important that their teeth are kept in good condition. Occasionally, it is difficult to gain the cooperation of a disadvantaged person who needs dental treatment; in such cases, general anaesthesia may be required even for a simple procedure. In the case of patients who have suffered a stroke, mouth care is particularly important. As recognised by Brady et al (2007), a stroke may result in physical weakness, lack of coordination and cognitive problems, all which may impact on the ability to maintain effective oral hygiene.

The older person

More people now retain their natural teeth into later life, and dentures are no longer an inevitable consequence of old age (Holman et al 2005). Good oral hygiene and regular assessment of oral/dental health for older people in hospital should form part of any nursing care plan (Box 15.3). However, Samaranayake et al (1995) found considerable unmet dental need among a group of 147 older people in five long-stay wards. Oral diseases are usually progressive and cumulative, and older people in general have a high prevalence of co-morbidities, health care challenges, and barriers to care, such as:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree