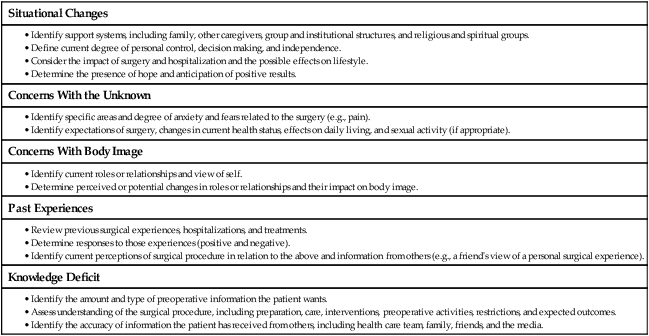

1. Differentiate the common purposes and settings of surgery. 2. Apply knowledge of the purpose and components of a preoperative nursing assessment. 3. Interpret the significance of data related to the preoperative patient’s health status and operative risk. 4. Analyze the components and purpose of informed consent for surgery. 5. Examine the nursing role in the physical, psychologic, and educational preparation of the surgical patient. 6. Prioritize the nursing responsibilities related to day-of-surgery preparation for the surgical patient. 7. Differentiate the purposes and types of common preoperative medications. 8. Apply knowledge of the special considerations of preoperative preparation for the older adult surgical patient. • Diagnosis: Determination of the presence and extent of a pathologic condition (e.g., lymph node biopsy, bronchoscopy). • Cure: Elimination or repair of a pathologic condition (e.g., removal of ruptured appendix or benign ovarian cyst). • Palliation: Alleviation of symptoms without cure (e.g., cutting a nerve root [rhizotomy] to remove symptoms of pain, creating a colostomy to bypass an inoperable bowel obstruction). • Prevention (e.g., removal of a mole before it becomes malignant, removal of the colon in a patient with familial polyposis to prevent cancer). • Cosmetic improvement (e.g., repairing a burn scar, breast reconstruction after a mastectomy). • Exploration: Surgical examination to determine the nature or extent of a disease (e.g., laparotomy). With the advent of advanced diagnostic tests, exploration is less common because problems can be identified earlier and easier. Specific suffixes are commonly used in combination with a body part or organ in naming surgical procedures (Table 18-1). TABLE 18-1 SUFFIXES DESCRIBING SURGICAL PROCEDURES • Determine the patient’s psychologic status in order to reinforce the use of coping strategies during the surgical experience. • Determine physiologic factors directly or indirectly related to the surgical procedure that may contribute to operative risk factors. • Establish baseline data for comparison in the intraoperative and postoperative period. • Participate in the identification and documentation of the surgical site and/or side (of body) on which the surgical procedure will be performed. • Identify prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, and herbal supplements taken by the patient that may result in drug interactions affecting the surgical outcome. • Document the results of all preoperative laboratory and diagnostic tests in the patient’s record, and communicate this information to appropriate health care providers. • Identify cultural and ethnic factors that may affect the surgical experience. • Determine if the patient has received adequate information from the surgeon to make an informed decision to have surgery and that the consent form is signed and witnessed. Your role in psychologically preparing the patient for surgery is to assess the patient for potential stressors that could negatively affect surgery (Table 18-2). Communicate all concerns to the appropriate surgical team member, especially if the concern requires intervention later in the surgical experience. Because many patients are admitted directly into the preoperative area from their homes, you must be skilled in assessing important psychologic factors in a short time. The most common psychologic factors are anxiety, fear, and hope. TABLE 18-2 PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF PREOPERATIVE PATIENT The patient may experience anxiety when surgery is in conflict with his or her religious and cultural beliefs. In particular, identify, document, and communicate the patient’s religious and cultural beliefs about the possibility of blood transfusions. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses may choose to refuse blood or blood products.1 Fear of pain and discomfort during and after surgery is common. If the fear is extreme, notify the ACP or the surgeon. Reassure the patient that drugs are available for both anesthesia and analgesia during surgery. For pain after surgery, tell patients to ask for pain medication before pain becomes severe. Instruct the patient on the use of a pain intensity scale (e.g., 0 to 10, FACES [see eFig. 9-3, available on the website for Chapter 9]). (Pain scales are explained in Chapter 9.) Although many psychologic factors related to surgery seem to be negative, hope is a positive attribute.2 Hope may be the patient’s strongest method of coping. To deny or minimize hope may negate the positive mental attitude necessary for a quick and full recovery. Some surgeries are hopefully anticipated. These can be the surgeries that repair (e.g., plastic surgery for burn scars), rebuild (e.g., total joint replacement to reduce pain and improve function), or save and extend life (e.g., repair of aneurysm, organ transplant). Assess and support the presence of hope and the patient’s anticipation of positive results. When obtaining a family health history, ask both patient and caregiver about any inherited traits, since they may contribute to the surgical outcome. Record any family history of cardiac and endocrine diseases. For example, if a patient reports a parent with hypertension, sudden cardiac death, or myocardial infarction, this should alert you to the possibility that the patient may have a similar predisposition or condition. Also obtain information about the patient’s family history of adverse reactions to or problems with anesthesia. For example, malignant hyperthermia has a genetic predisposition. Measures to decrease complications associated with this condition can be taken. (For further information on malignant hyperthermia, see Chapter 19.) The interaction of the patient’s current medications and anesthetics can increase or decrease the desired physiologic effect of anesthetics. Consider the effects of opioids and prescribed medications for chronic health conditions (e.g., heart disease, hypertension, depression, epilepsy, diabetes mellitus). For example, certain antidepressants can potentiate the effect of opioids, agents that can be used for anesthesia. Antihypertensive drugs may predispose the patient to shock from the combined effect of the drug and the vasodilator effect of some anesthetic agents. Insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents may require dose or agent adjustments during the perioperative period because of increased body metabolism, decreased oral intake, stress, and anesthesia. Antiplatelet drugs (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel [Plavix]) and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit platelet aggregation and may contribute to postoperative bleeding. Surgeons may instruct patients to withhold these medications before surgery. Specific timeframes for withholding drugs depend on the drug and the patient. Patients on long-term anticoagulation therapy (e.g., warfarin [Coumadin]) present a unique challenge. The options for these patients include (1) continuing therapy, (2) withholding therapy for a time before and after surgery, or (3) withholding the therapy and starting subcutaneous or IV heparin therapy during the perioperative period. The management strategy selected is determined by patient characteristics and the nature of the surgery.3 Ask about the use of herbs and dietary supplements because their use is so common. Many patients do not think to include supplements in their list of medications. They believe that herbal and dietary supplements are “natural” and do not pose a surgical risk.4 (See the Complementary & Alternative Therapies box in Chapter 3 on p. 39 on how to assess for the use of herbal supplements.) Excessive use of vitamins and herbs can cause harmful effects in patients undergoing surgery. In patients taking anticoagulants or antiplatelets, herbal supplements can produce excessive postoperative bleeding that may require a return to the OR.5 The effects of specific herbs that are of concern during the perioperative period are listed below in the Complementary & Alternative Therapies box. Also ask the patient about possible recreational drug use, abuse, and addiction. The substances most likely to be abused include tobacco, alcohol, opioids, marijuana, cocaine, and amphetamines. Ask questions about the use of these substances in a frank manner. Stress that recreational drug use may affect the type and amount of anesthesia that will be needed. When patients become aware of the potential interactions of these substances with anesthetics, most patients respond honestly about using them. Chronic alcohol use can place the patient at risk because of lung, gastrointestinal, or liver damage. When liver function is decreased, metabolism of anesthetic agents is prolonged, nutritional status is altered, and the potential for postoperative complications is increased. Alcohol withdrawal can also occur during lengthy surgery or in the postoperative period. Although this can be a life-threatening event, it can be avoided with appropriate planning and management (see Chapter 11). Risk factors for latex allergy include long-term, multiple exposures to latex products, such as those experienced by health care and rubber industry workers. Additional risk factors include a history of hay fever, asthma, and allergies to certain foods (e.g., eggs, avocados, bananas, chestnuts, potatoes, peaches).6 (Latex allergies are discussed in Chapter 14.) If indicated, a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and coagulation studies should be ordered, and the results should be on the chart before surgery. The CV assessment provides data on what other measures need to be done. For example, the patient who is on diuretic therapy will need to have a serum potassium level drawn preoperatively. If the patient has a history of hypertension, the ACP may administer vasoactive drugs to maintain adequate BP during surgery. If the patient has a history of valvular heart disease, antibiotic prophylaxis often is given before surgery to decrease the risk of bacterial endocarditis (see Chapter 37). Postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE), a condition that includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a concern for any surgical patient. Patients at high risk for VTE include those with a history of previous thrombosis, blood-clotting disorders, cancer, varicosities, obesity, smoking, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).7 People are also at risk for developing a VTE because of immobility and positioning during the operative procedure. Antiembolism stockings or sequential compression devices may be applied to the legs in the preoperative holding area. Preoperative assessment of the older person’s baseline cognitive function is especially crucial for intraoperative and postoperative evaluation.8 The older adult may have intact mental abilities preoperatively, but is more prone to adverse outcomes during and after surgery than the younger adult. This is due to the additional stressors of the surgical procedure, dehydration, hypothermia, and anesthesia and adjunctive medications. These factors may contribute to the development of emergence delirium (“waking up wild”), a condition that may be falsely labeled as senility or dementia. Thus preoperative findings are critical for postoperative comparison. For women of childbearing age, determine if they are pregnant or think they could be pregnant. Most institutions require a pregnancy test for all women of childbearing age before surgery.9 Immediately inform the surgeon if the patient states that she might be pregnant, since maternal and subsequent fetal exposure to anesthetics during the first trimester should be avoided. The patient with Addison’s disease also requires special consideration during surgery. Addisonian crisis or shock can occur if a patient abruptly stops taking replacement corticosteroids, and the stress of surgery may require additional IV corticosteroid therapy10 (see Chapter 50).

Nursing Management

Preoperative Care

Suffix

Meaning

Example

-ectomy

Excision or removal of

Appendectomy

-lysis

Destruction of

Electrolysis

-orrhaphy

Repair or suture of

Herniorrhaphy

-oscopy

Looking into

Endoscopy

-ostomy

Creation of opening into

Colostomy

-otomy

Cutting into or incision of

Tracheotomy

-plasty

Repair or reconstruction of

Mammoplasty

Nursing Assessment of Preoperative Patient

Subjective Data

Psychosocial Assessment.

Anxiety.

Common Fears.

Hope.

Past Health History.

Medications.

Allergies.

Review of Systems.

Cardiovascular System.

Neurologic System.

Genitourinary System.

Endocrine System.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Preoperative Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access