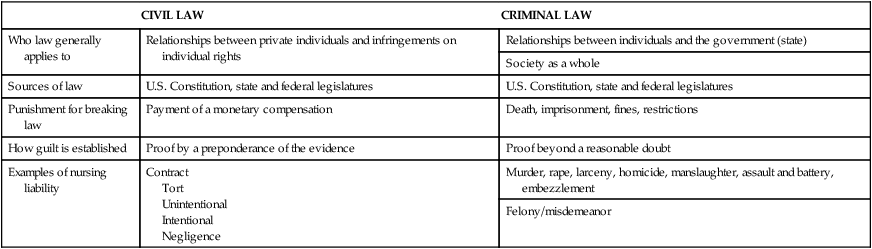

On completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss the content of your state’s Nurse Practice Act. 2. Describe the responsibilities of your state’s board of nursing (or nursing regulatory board). 3. Explain the limits of nursing licensure within your state. 4. Define the nursing standard of care. 5. Differentiate between common law and statutory law. 6. Explain the difference between criminal and civil action. 7. Discuss the difference between intentional and unintentional torts. 8. List the four elements needed for negligence. 9. Review the steps for bringing legal action. 10. Differentiate between practical/vocational nursing student (SPN/SVN) and instructor liability in preventing a lawsuit. 11. Summarize the American Hospital Association’s publication The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights, and Responsibilities. 12. Describe the major focus of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. 13. Discuss the differences among general consent, informed consent, and authorized consent. 14. Differentiate between the living will and durable power of attorney. 15. Explain the difference between physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. 16. Discuss the difference between a multistate compact and a border agreement. 17. Explain how you would legally deal with two difficult situations that might occur in a clinical setting. (ĂW-thŏr-izd kŏn-SĚNT, p. 143) (BŎR-dĕr rĕk-og-NĬ-shŭn, p. 132) (KŎM-plĕks NŬR-sēng sĭt-u-Ā-shŭn, p. 130) (kŏn-fĭ-dĕn-chē-ĂL-ĭ-tē, p. 139) (dĭ-RĚCT soo-pŭr-VĬ-shŭn, p. 130) durable medical power of attorney (JĚN-ĕr-ăl soo-pŭr-VĬ-shŭn, p. 130) Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (ĭn-stĭ-TOO-shŭn-ăl lī-ă-BĬL-ĭ-tē, p. 138) (ĭn-TĚN-shŭn-ăl tŏrts, p. 134) (ĭn-tĕr-STĀT ĭn-DŎRS-mĕnt, p. 132) malpractice (professional negligence) multistate licensure (Nurse Licensure Compact) (PĀ-shĕnt KŎM-pĕ-tĕn-sē, p. 142) Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) (PĚR-sŭn-ăl lī-ă-BĬL-ĭ-tē, p. 137) physician-assisted suicide (PAS) (fĭ-ZĬ-shŭn ă-SĬS-tĕd SOO-ĭ-sīd, p. 144) The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights, and Responsibilities (ŭn-ĭn-TĚN-shŭn-ăl tŏrts p. 134) • Basic nursing care. Nursing care that can be performed safely by the LPN/LVN, based on knowledge and skills gained during the educational program. Modifications of care are unnecessary, and patient response is predictable. • Basic patient situation. The patient’s clinical condition is predictable. Medical and nursing orders are not changing continuously. These orders do not contain complex modifications. The patient’s clinical condition requires only basic nursing care. The professional nurse assesses whether the situation is a basic patient situation. • Complex nursing situation. The patient’s clinical condition is not predictable. Medical orders or nursing interventions are likely to involve continuous changes or complex modifications. Nursing care expectations are beyond those learned by the LPN/LVN during the educational program. The professional nurse assesses whether the situation is a complex nursing situation. • Delegated medical act. During a delegated medical act, a physician’s order is given to a registered nurse (RN), an LPN, or an LVN by a physician, dentist, or podiatrist. • Delegated nursing act. In a delegated nursing act, an RN gives nursing orders to an RN, LPN, or LVN. • Direct supervision. With direct supervision, the supervisor is continuously present to coordinate, direct, or inspect nursing care. The supervisor is in the building. • General supervision. Under general supervision, a supervisor regularly coordinates, directs, or inspects nursing care and is within reach either in the building or by telephone. State boards of nursing (sometimes called nurse regulatory boards) have committees or councils that decide whether specific activities are within the scope of LPN/LVN practice in their state. An activity that is legal in one state may not be legal in another state. See Box 12-1 for common board of nursing functions. Each state’s Nurse Practice Act lists specific reasons for which they seek to discipline a nurse. Eight general categories of disciplinary actions can be taken against nurses. Brent (2001) lists them as “fraud and deceit; criminal activity; negligence; risk to patients because of physical or mental incapacity; violation of the Nurse Practice Act or rules; disciplinary action by another board; incompetence; unethical conduct; and drug and/or alcohol use.” See Box 12-2 for the eight categories of disciplinary action. The disciplinary process is based on law and follows the rules of law. See Box 12-3 for the steps of a disciplinary process. The use of unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) to provide patient care has grown dramatically in recent years. It is expected that the trend will continue. These unlicensed persons are trained to perform a variety of nursing tasks. Licensed nurses need to be aware of specific training that UAPs have had and facility job descriptions so they can safely make assignments. Supervision of UAPs by the RN and the LPN/LVN charge nurse in long-term care to ensure safety of patient care is a major concern. There is concern that because of the lack of licensed nurses in an agency, duties might be delegated and/or assigned inappropriately to UAPs. It is the RNs and LPNs/LVNs who stand to lose their jobs and licenses if the care provided by UAPs does not meet the standards of safety and effectiveness. The training program for UAPs does not provide the same in-depth education and experience that programs for student nurses provide. Licensed nurses are also accountable to both their employers and their state nursing boards (see Chapter 21). The nursing standard of care is your guideline for good nursing care. The phrase “You are held to the nursing standard of care” has important legal implications. The standard is based on what an ordinary, prudent nurse with similar education and nursing experience would do in similar circumstances. Resources for the nursing standard of care are found in Box 12-4. Note that unit routine (“I know you studied how to do this in nursing school, but this is how we do it here.”) is not on the list. • Misdemeanor: A misdemeanor is the least serious charge and can result in a fine or prison sentence of no more than 1 year. This criminal act might include taking a narcotic intended for the patient’s pain relief and giving the patient another substance in its place. • Felony: A felony is a serious offense with a penalty that ranges from more than 1 year in prison to death—for example, when the nurse injects a patient with a lethal drug to hasten death or removes life support before the patient has been pronounced dead by the physician. • Intentional: An intentional tort is intended to cause harm to the patient (e.g., threat or actual physical harm). • Unintentional: An unintentional tort did not mean to harm the patient. “I did not mean to hurt the patient” is no defense when you did not use the “Rule of 5” and gave the patient an incorrect medication, which caused injury. Guilt on the part of the nurse can be established by a preponderance (majority) of the evidence. Table 12-1 provides a comparison of criminal and civil law. Table 12-1 Comparison of Two Basic Classifications of Law

Nursing and the Law

What Are the Rules?

Nurse practice act

Basic terminology

State board of nursing

Functions of the board

Disciplinary responsibility of the board

Disciplinary process and action

Unlicensed assistive personnel

Nursing standard of care

Criminal versus civil action

CIVIL LAW

CRIMINAL LAW

Who law generally applies to

Relationships between private individuals and infringements on individual rights

Relationships between individuals and the government (state)

Society as a whole

Sources of law

U.S. Constitution, state and federal legislatures

U.S. Constitution, state and federal legislatures

Punishment for breaking law

Payment of a monetary compensation

Death, imprisonment, fines, restrictions

How guilt is established

Proof by a preponderance of the evidence

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt

Examples of nursing liability

Contract

Tort

Unintentional

Intentional

Negligence

Murder, rape, larceny, homicide, manslaughter, assault and battery, embezzlement

Felony/misdemeanor

Intentional torts

Nursing and the Law: What Are the Rules?

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access