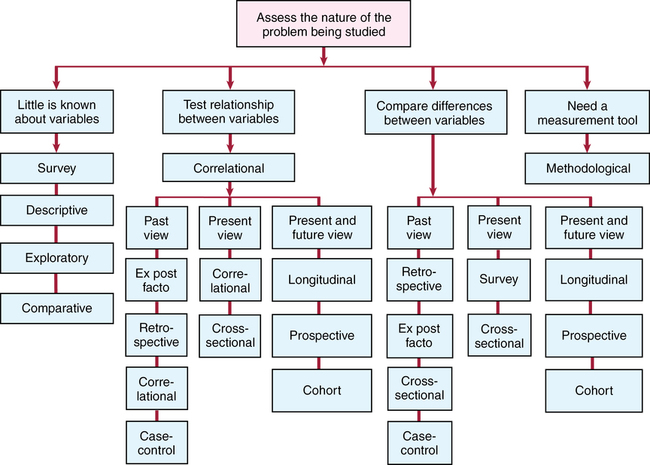

CHAPTER 10 Geri LoBiondo-Wood and Judith Haber After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Describe the overall purpose of nonexperimental designs. • Describe the characteristics of survey, relationship, and difference designs. • Define the differences between survey, relationship, and difference designs. List the advantages and disadvantages of surveys and each type of relationship and difference designs. • Identify methodological and secondary analysis methods of research. • Identify the purposes of methodological and secondary analysis methods of research. • Describe the purposes of a systematic review, meta-analysis, integrative review, and clinical practice guidelines. • Define the differences between a systematic review, meta-analysis, integrative review, and clinical practice guidelines. • Discuss relational inferences versus causal inferences as they relate to nonexperimental designs. • Identify the critical appraisal criteria used to critique nonexperimental research designs. • Apply the critiquing criteria to the evaluation of nonexperimental research designs as they appear in research reports. • Apply the critiquing criteria to the evaluation of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. • Evaluate the strength and quality of evidence by nonexperimental designs. • Evaluate the strength and quality of evidence provided by systematic reviews, meta-analysis, integrative reviews, and clinical practice guidelines. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. In experimental research the independent variable is actively manipulated; in nonexperimental research it is not. In nonexperimental research the independent variables have naturally occurred, so to speak, and the investigator cannot directly control them by manipulation. In a nonexperimental design the researcher explores relationships or differences among the variables. Even though the researcher does not actively manipulate the variables, the concepts of control and potential sources of bias (see Chapter 8) should be considered as much as possible. Nonexperimental research designs provide Level IV evidence. The strength of evidence provided by nonexperimental designs is not as strong as that for experimental designs because there is a different degree of control within the study; that is, the independent variable is not manipulated, subjects are not randomized, and there is no control group. Yet the information yielded by these types of studies is critical to developing a base of evidence for practice and may represent the best evidence available to answer research or clinical questions. Researchers are not in agreement on how to classify nonexperimental studies. A continuum of quantitative research design is presented in Figure 10-1. Nonexperimental studies explore the relationships or the differences between variables. This chapter divides nonexperimental designs into survey studies and relationship/difference studies as illustrated in Box 10-1. These categories are somewhat flexible, and other sources may classify nonexperimental studies in a different way. Some studies fall exclusively within one of these categories, whereas many other studies have characteristics of more than one category (Table 10-1). As you read the research literature you will often find that researchers who are conducting a nonexperimental study use several design classifications for one study. This chapter introduces the various types of nonexperimental designs and discusses their advantages and disadvantages, the use of nonexperimental research, the issues of causality, and the critiquing process as it relates to nonexperimental research. The Critical Thinking Decision Path outlines the path to the choice of a nonexperimental design. TABLE 10-1 EXAMPLES OF STUDIES WITH MORE THAN ONE DESIGN LABEL The broadest category of nonexperimental designs is the survey study. Survey studies are further classified as descriptive, exploratory, or comparative. Surveys collect detailed descriptions of variables and use the data to justify and assess conditions and practices or to make plans for improving health care practices. You will find that the terms exploratory, descriptive, comparative, and survey are used either alone, interchangeably, or together to describe a study’s design (see Table 10-1). • Investigators use a survey design to search for accurate information about the characteristics of particular subjects, groups, institutions, or situations or about the frequency of a variable’s occurrence, particularly when little is known about the variable. Box 10-2 provides examples of survey studies. • The types of variables in a survey can be classified as opinions, attitudes, or facts. • Fact variables include attributes of an individual such as gender, income level, political and religious affiliations, ethnicity, occupation, and educational level. • Surveys provide the basis for further development of programs and interventions. • Surveys are described as comparative when used to determine differences between variables. • Survey data can be collected with a questionnaire or an interview (see Chapter 14). • Surveys have either small or large samples of subjects drawn from defined populations, can be either broad or narrow, and can be made up of people or institutions. • The data might provide the basis for projecting programmatic needs of groups. • A survey’s scope and depth depend on the nature of the problem. • Surveys attempt to relate one variable to another or assess differences between variables, but do not determine causation. The advantages of surveys are that a great deal of information can be obtained from a large population in a fairly economical manner, and that survey research information can be surprisingly accurate. If a sample is representative of the population (see Chapter 12), even a relatively small number of subjects can provide an accurate picture of the population. • Not testing whether one variable causes another variable. • Testing whether the variables co-vary; that is, as one variable changes, does a related change occur in another variable. • Interested in quantifying the strength of the relationship between variables, or in testing a hypothesis or research question about a specific relationship. The direction of the relationship is important (see Chapter 16 for an explanation of the correlation coefficient). For example, in their correlational study, Pinar and colleagues (2012) assessed the relationship between social support and anxiety levels, depression, and quality of life in Turkish women with gynecologic cancer. This study tested multiple variables to assess the relationship and differences among the sample. The researchers concluded that having higher levels of social support were significantly related to lower levels of depression and anxiety, and higher levels of quality of life. Thus the variables were related to (not causal of) outcomes. Each step of this study was consistent with the aims of exploring the relationship among variables. • An increased flexibility when investigating complex relationships among variables. • An efficient and effective method of collecting a large amount of data about a problem. • A potential for evidence-based application in clinical settings. • A potential foundation for future experimental research studies. • A framework for exploring the relationship between variables that cannot be inherently manipulated. • A correlational study has a quality of realism and is appealing because it can suggest the potential for practical solutions to clinical problems. The following are disadvantages of correlational studies: • The researcher is unable to manipulate the variables of interest. • The researcher does not use randomization in the sampling procedures as the groups are preexisting and therefore generalizability is decreased. • The researcher is unable to determine a causal relationship between the variables because of the lack of manipulation, control, and randomization. • The strength and quality of evidence is limited by the associative nature of the relationship between the variables. • A misuse of a correlational design would be if the researcher concluded that a causal relationship exists between the variables. There are also classifications of nonexperimental designs that use a time perspective. Investigators who use developmental studies are concerned not only with the existing status and the relationship and differences among phenomena at one point in time, but also with changes that result from elapsed time. The following three types of developmental study designs are discussed: cross-sectional, longitudinal, cohort or prospective and retrospective (also labeled as ex post facto or case control). Remember that in the literature, however, studies may be designated by more than one design name. This practice is accepted because many studies have elements of several designs. Table 10-1 provides examples of studies classified with more than one design label. A cross-sectional study examines data at one point in time; that is, data collected on only one occasion with the same subjects rather than with the same subjects at several time points. For example, in a study of post-traumatic stress symptoms Melvin and colleagues (2012; see Appendix D) hypothesized that couple functioning, as perceived by each member of the couple, would be negatively associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS). This study tested multiple variables (age, gender, military ranks, and marital stress) to assess the relationship and differences among the sample. The researchers concluded that having higher levels of PTSS were associated with lower couple functioning and resilience, thus the variables were related to (not causal of) outcomes. Each step of this study was consistent with the aims of exploring the relationship and differences among variables in a cross-sectional design.

Nonexperimental designs

DESIGN TYPE

STUDY’S PURPOSE

Descriptive, longitudinal with retrospective, longitudinal with medical records review

To assess patient and provider responses to a computerized symptom assessment system (Carpenter et al., 2008)

Descriptive, exploratory, secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

To identify the predictors of fatigue 30 days after completing adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer and whether differences are observed between a sleep intervention and a healthy eating attention control group in predicting fatigue (Wielgus et al., 2009)

Longitudinal, descriptive

This longitudinal, descriptive study was conducted to examine the relationships of maternal-fetal attachment, health practices during pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (Alhusen et al., 2012)

Survey studies

Relationship and difference studies

Correlational studies

Developmental studies

Cross-sectional studies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree