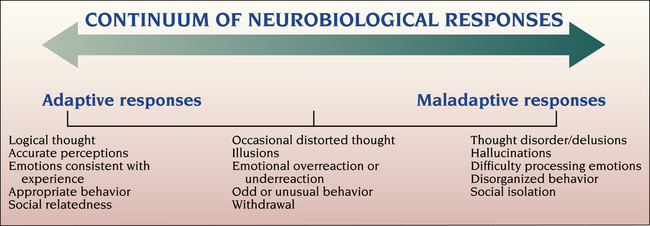

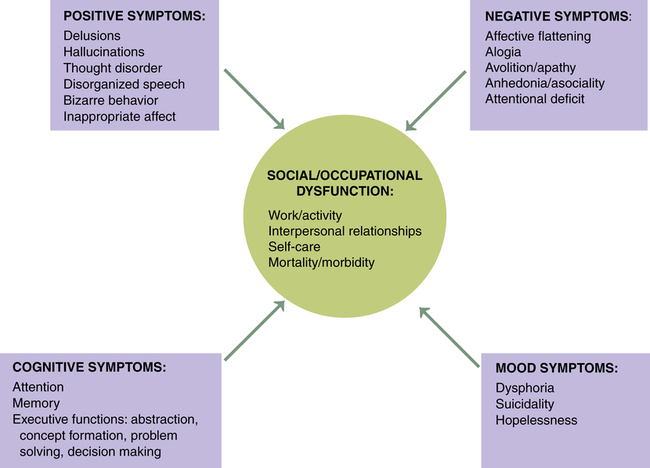

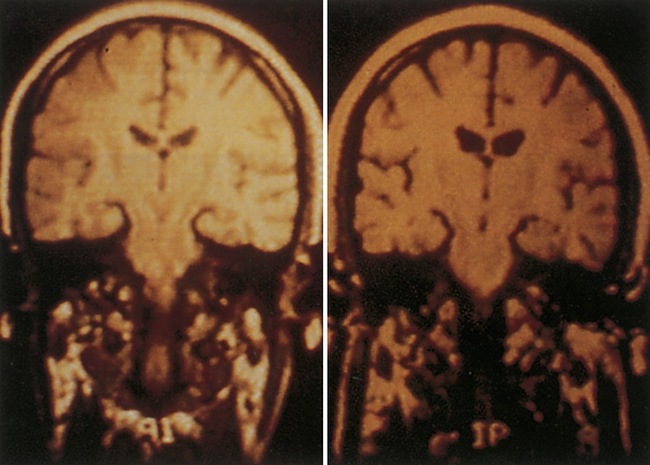

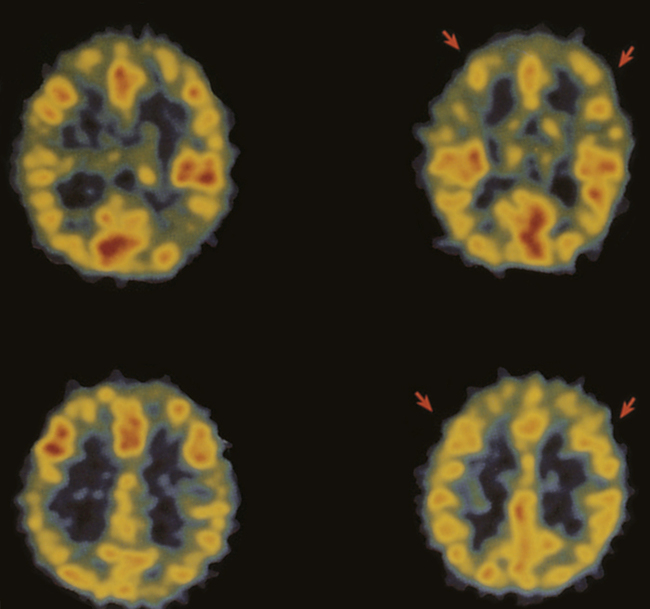

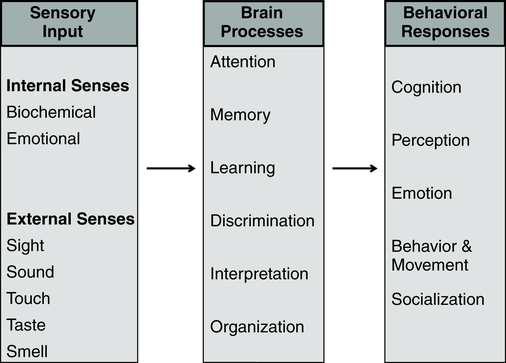

1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive neurobiological responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with maladaptive neurobiological responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 8. Develop a family education plan to promote adaptive neurobiological responses. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. 10. Evaluate nursing care related to maladaptive neurobiological responses. The overall goal of nursing care is to help the patient recognize the psychosis and develop strategies to manage the symptoms and achieve recovery. It is important to remember that these are complex neurobiological brain diseases affecting one’s ability to perceive and process information. The behaviors associated with psychosis are difficult to understand, are usually severe, and can be long lasting. Box 20-1 describes one person’s experience with psychosis. The range of neurobiological responses includes a continuum from adaptive responses, such as logical thought and accurate perceptions, to maladaptive responses, such as thought distortions and hallucinations. The symptoms of psychosis are at the maladaptive end of this continuum (Figure 20-1). Schizophrenia is a serious and persistent neurobiological brain disease. It results in responses that can severely impair the lives of individuals, their families, and communities. Box 20-2 presents information on the impact of schizophrenia on the individual and society. Schizophrenia is one of a group of psychotic disorders. Other psychotic disorders include schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, shared psychotic disorder (folie a deux), psychotic disorder caused by a general medical condition, and substance-induced psychotic disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). About 50% of patients with schizophrenia have a co-occurring substance use disorder, most frequently alcohol or cannabis. These patients often have more severe symptoms; increased rates of hospitalization, violence, victimization, homelessness, and nonadherence to medication; and poor overall response to medication (Schmidt et al, 2011). One way of categorizing the symptoms of schizophrenia lists them as positive symptoms (exaggerated normal behaviors) and negative symptoms (diminished normal behaviors) (Box 20-3). Another system defines five core symptom clusters, presented in Figure 20-2. This model incorporates the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia as well as other aspects, including cognitive symptoms, mood symptoms, and some of the social and occupational dysfunctions common in schizophrenia. Cognition is the act or process of knowing. It involves awareness and judgment that allows the brain to process information in a way that provides accuracy, storage, and retrieval. People with schizophrenia are often unable to produce complex logical thoughts or express coherent sentences because neurotransmission in the brain’s information processing system is malfunctioning. These cognitive deficits are often present in patients who are at clinical high risk for psychosis before the onset of psychotic illness (Carrion et al, 2011). Information processing involves the organization of sensory input by brain processes into behavioral responses (Figure 20-3). Sensory input from both internal and external senses is screened according to the focus of the person’s attention and ability to remember, learn, discriminate, interpret, and organize information. The result is seen in the person’s thinking, perceiving, feeling, behavior, and relatedness to others. People with schizophrenia tend to overestimate or underestimate their own capability. The abnormal brain dysfunction during an acute episode of schizophrenia makes it difficult for patients to realize that they need help. This lack of insight is a neurological deficit involving the frontal and prefrontal lobes of the brain. It is called anosognosia, a condition in which the patient does not recognize that there is anything wrong or that there are deficits of any kind (Amador, 2007). Symptoms related to problems in information processing associated with schizophrenia are often called cognitive deficits. They include problems with cognitive functioning in all aspects of memory, attention, form and organization of speech, decision making, and thought content (Box 20-4). Form and organization of speech are at the core of communication. Problems in information processing can result in incoherent communication. Problems with form and organization of speech (formal thought disorders) may include loose associations, word salad, tangentiality, illogicality, circumstantiality, pressured speech, poverty of speech, distractible speech, and clanging. These behaviors are described in Chapter 6. Box 20-5 presents nurse-patient dialogues that reflect problems in the form and organization of speech related to psychotic disorders. The inability of the brain to process data accurately can result in paranoid, grandiose, religious, nihilistic, and somatic delusions. The delusions can be complicated further by thought withdrawal, thought insertion, thought control, or thought broadcasting. The various types of delusions are described in Chapter 6. Hallucinations are false perceptual distortions that occur in maladaptive neurobiological responses. The patient actually experiences the sensory distortion as being real and responds accordingly. However, with a hallucination, there is no identifiable external or internal stimulus. Hallucinations can arise from any of the five senses, as described in Table 20-1. TABLE 20-1 SENSORY MODALITIES INVOLVED IN HALLUCINATIONS Box 20-6 lists several neurological soft and hard signs commonly seen in schizophrenia that should be assessed carefully during a baseline evaluation of each patient. Problems in these functions contribute to difficulty with fine motor actions of the hand, and the patient may appear clumsy. Problems with right/left discrimination also contribute to a lack of coordination and ability to carry out directions involving concepts of right and left. Terms related to affect include broad, restricted, blunted, flat, and inappropriate (see Chapter 6). What is considered normal varies greatly among cultures. Broad or restricted affect is usually considered to be within the range of normal, whereas blunted, flat, or inappropriate affect represents symptoms of an underlying problem. Disorders of affect refer to the expression of emotion, not the experience of emotion. Patients describe affective symptoms in the following examples: • “I remember trying to smile for 3 years, but my face did not work.” • “My face was as stiff as your fingers would be if you tied them to popsicle sticks for 3 months and then tried to use them to thread a needle.” • Alexithymia: difficulty naming and describing emotions • Anhedonia: inability or decreased ability to experience pleasure, joy, intimacy, and closeness Stigma also presents major obstacles to developing relationships and adversely affects quality of life. It is a major cause of the social isolation of people with schizophrenia, and it often spreads to the whole family, who may be having their own schizophrenia-related social problems stemming from embarrassment about having the illness in the family (Marcussen et al, 2010; McCann et al, 2011). They may avoid talking about it, or if they do want to talk, they may not know how to broach the subject. Stigma and rejection may discourage them from talking. Family members may feel like social outcasts for having this illness in the family (see Chapter 10). One family member explained, “For the rest of my life, I will be dealing not only with the heartbreak of my brother’s illness but also with negative response, stigma, and ignorance in my hometown that affects me deeply.” Individuals with schizophrenia have higher morbidity and mortality because of physical illness (Lawrence et al, 2010; Platt et al, 2010; Jeste et al, 2011). These conditions, especially obesity and its cardiovascular consequences, lead to the well-documented shortening of the average life span in persons with schizophrenia by about 20 years. In addition, persons with schizophrenia who are hospitalized for medical or surgical reasons have twice the chance of adverse events, associated with poorer clinical and economic outcomes. Part of the problem is the high-risk lifestyle of persons with schizophrenia, which includes sedentary living, smoking, unhealthy dietary habits, and obesity. This can result in diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease (Megna et al, 2011). Atypical antipsychotics also contribute to these medical conditions. In addition, there is a serious disparity of health care for patients with severe mental illness, with neither the primary care system nor the mental health system providing basic physical health screening, treatment, and monitoring for these individuals (Kreyenbuhl et al, 2010; Minsky et al, 2011). Thus it is essential that nurses complete a thorough biological assessment of these patients (see Chapter 5) to fully evaluate their physical health needs (Roberts and Bailey, 2011). This assessment should include scheduling of cancer screening, vision tests, and other preventive examinations. Then a biopsychosocial treatment plan should be developed that ensures adequate monitoring of body mass index, plasma glucose level, lipid profiles, and signs of prolactin elevation or sexual dysfunction, among other indicators. Schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental brain disorder. No one thing causes schizophrenia. It is the end result of a complex interaction among thousands of genes and many environmental risk factors, none of which on its own causes schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a complex neurobiological disorder of brain neurotransmitter circuits, neuroanatomical deficits, neuroelectrical abnormalities, and neurocirculatory dysregulation. These ultimately lead to a miswired brain and clinical symptoms (Gilmore, 2010). Genetics plays a role in schizophrenia but it is difficult to separate out the influence of genetics and the environment. The aim of genetic research is to eventually map the genetic susceptibility for schizophrenia and then develop genetic interventions as treatment modalities. The specific genetic defects that cause schizophrenia have not yet been identified, but progress has been made toward identifying the mechanisms and potential gene locations (MacDonald and Schulz, 2009). The most significant risk factor for developing schizophrenia is having a first-degree relative with schizophrenia. Family, twin, and adoption studies have shown an increased risk for the disease in people with both a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, offspring) or a second-degree relative (grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, grandchildren) with schizophrenia (Gottesman et al, 2010). More than 40% of monozygotic twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected. However most people with schizophrenia do not have an affected relative, and while the overall genetic contribution to schizophrenia may be large, the contribution of specific genes is very small. The decreased brain volume includes decreases in both gray matter and white matter (neuronal axons) (Arnsten, 2011). This is due to faulty myelination occurring at about age 6 years and again at about age 13 years and relates to a theory of abnormal pruning of neurons during adolescence (Faludi and Mirnics, 2011). Particular attention has been focused on the following: • Frontal cortex, implicated in the negative symptoms of schizophrenia • Limbic system (in the temporal lobes), implicated in the positive symptoms of schizophrenia • Neurotransmitter systems connecting these regions, particularly dopamine and serotonin, and more recently, glutamate Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging studies of brain structure show decreased brain volume in people with schizophrenia (Figure 20-4). Findings include: • Larger lateral and third ventricles • Decreased gray matter volume in the hippocampus, caudate nucleus, thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and cerebellum • Atrophy in the frontal lobe and limbic structures (particularly the hippocampus and amygdala) • Increased size of sulci (fissures) on the surface of the brain Positron emission tomography scans usually demonstrate decreased cerebral blood flow to the frontal lobes during specific cognitive tasks in people with schizophrenia. This frontal hypometabolism is thought to account for some problems with attention, planning, and decision making (Figure 20-5).

Neurobiological Responses and Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders

Continuum of Neurobiological Responses

Assessment

Behaviors

Cognition

Form and organization of speech

Thought content

Perception

SENSE

CHARACTERISTICS

Auditory

Hearing noises or sounds, most commonly in the form of voices. Sounds that range from a simple noise or voice, to a voice talking about the patient, to complete conversations between two or more people about the person who is hallucinating.

Audible thoughts in which the patient hears voices that are speaking what the patient is thinking and commands that tell the patient to do something, sometimes harmful or dangerous.

Visual

Visual stimuli in the form of flashes of light, geometric figures, cartoon figures, or elaborate and complex scenes or visions. Visions can be pleasant or terrifying, as in seeing monsters.

Olfactory

Putrid, foul, and rancid smells such as blood, urine, or feces; occasionally the odors can be pleasant. Olfactory hallucinations are typically associated with stroke, tumor, seizures, and the dementias.

Gustatory

Putrid, foul, and rancid tastes such as blood, urine, or feces.

Tactile

Experiencing pain or discomfort with no apparent stimuli. Feeling electrical sensations coming from the ground, inanimate objects, or other people.

Cenesthetic

Feeling body functions such as blood pulsing through veins and arteries, food digesting, or urine forming.

Kinesthetic

Sensation of movement while standing motionless.

Emotion

Socialization

Physical Health

Predisposing Factors

Genetics

Neurobiology

Imaging studies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree