Introduction

Midwives must be able to resuscitate both the newborn baby and the mother, and therefore they should receive annual neonatal and maternal resuscitation training. This training should also cover standard adult resuscitation.

Incidence and facts

- In the developed world around 5–10% of newborn babies require some degree of intervention at birth; typically active stimulation. This number is higher in the developing world (Ergenekon et al., 2000).

- 1% of babies >2.5 kg require assisted ventilation and 20% of these need intubation.

- Occasionally babies are born unexpectedly ‘flat’, but this can be managed effectively by basic resuscitation techniques (Palme-Kilander, 1992). Only 0.2% of ‘low-risk birth’ babies require assisted ventilation, and only 10% of these require intubation (Palme-Kilander, 1992).

- It has been estimated that up to 800 000 newborn babies who currently die could be saved by timely basic resuscitation techniques (Zideman et al., 1998), primarily prompt aerating of the lungs (Biarent et al., 2005; Resuscitation Council UK, 2005b).

- Anticipation is the most important aspect of resuscitation; equipment and personnel should be assembled as soon as possible for suspected problems.

Risk management: anticipation

Many situations may result in a newborn baby requiring active resuscitation (Box 17.1). Also, any unexpected birth in the community or the emergency department, although usually uneventful, may present problems.

Box 17.1 Resuscitation anticipation: Risk factors.

- Maternal diabetes

- Pre-eclampsia/essential hypertension

- Chronic maternal illness (e.g. cardiovascular, thyroid, pulmonary, renal and neurological)

- Previous stillbirth or neonatal death

- Antepartum haemorrhage

- Oligo/polyhydramnios

- Size versus dates discrepancy/reduced fetal movements

- Alcohol or drugs misuse

- Other drugs, e.g. lithium carbonate, magnesium and adrenergic-blocking drugs

- No antenatal care

- Preterm birth

- Prolonged rupture of membranes/infection, e.g. chorioamnionitis

- Abnormal fetal heart rate, e.g. bradycardia, tachycardia and prolonged decelerations

- Meconium-stained liquor

- Breech or malpresentation

- Recent maternal opioid analgesia (<4 hours)

- Cord prolapse

- Placenta praevia/abruption

- Fetal abnormality

- Instrumental or operative delivery

- General anaesthetic

Once a ‘high-risk’ birth is identified, a clinician trained in newborn resuscitation (e.g. paediatrician or advanced neonatal practitioner) should be summoned before birth (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health & Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCPCH & RCOG), 1997). Midwives caring for women at home or in a birthing centre should be aware of factors that can influence the baby’s condition at birth and that may necessitate transfer. For a list of community midwife’s resuscitation equipment, see Box 17.2.

Box 17.2 Resuscitation equipment for home birth.

- Suction device

- O2 funnel

- Self-inflating 500 ml bag-mask-valve device

- The use of the 500 ml BVM device in association with a slow, steady and controlled breath will reduce the risk of under-ventilation and/or barotrauma. The traditional 240 ml BVM device is no longer recommended as it is difficult to provide a slow constant inflation pressure (Zideman et al., 1998)

- Oxygen cylinder with variable flow meter

- Suction device

- Oxygen mask (medium concentration)

- Pocket mask with one-way valve and various oral airways

- BVM device (optional – as the above pocket mask using oxygen is effective for basic life support)

- Oxygen cylinder with variable flow meter

Basic neonatal resuscitation

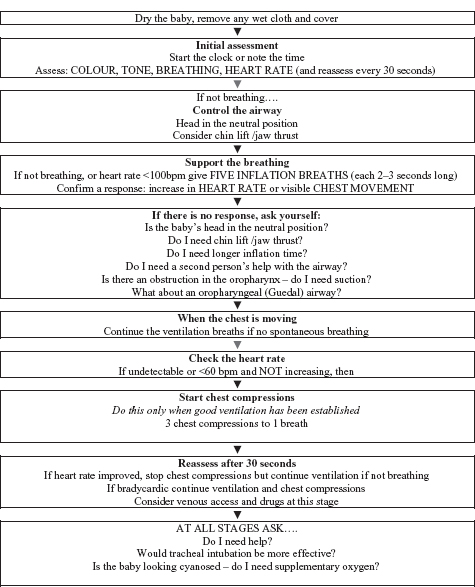

All previous newborn resuscitation guidelines have been superseded by the consensus document on resuscitation (Biarent et al., 2005). Successful neonatal resuscitation is based on anticipation, environmental control, assessment, stimulation, effective ventilation and, rarely, cardiac compressions with intubation and drug administration. Resuscitation involves a number of processes that occur simultaneously. Each step will be considered separately, although the initial assessment and stimulation should occur as one swift action (see Fig. 17.1).

Environment

It is essential that the newborn baby does not become cold, as acidosis is worsened by hypothermia (Tyson, 2000). Skin-to-skin contact immediately following birth is effective at maintaining/increasing the baby’s body temperature. In a hospital or birthing centre, an overhead heater, typically incorporated into a resuscitaire, should be available. Such equipment is not available in the community, so the attending midwife should minimise draughts, ensure that the area is warm and that warmed towels are available. Although this is common sense, it is typically simple procedures that are forgotten during the initial phase of any resuscitation attempt.

Assessment

A rapid assessment of tone, colour, respiratory rate, heart rate, and gut instinct that things are not right, will indicate the need to instigate resuscitation procedures. A stepwise approach is recommended in the assessment of the newborn that may require resuscitation, and this includes active stimulation and opening the airway.

ABC of neonatal resuscitation

Fig. 17.1 Neonatal life support algorithm (adapted from the Resuscitation Council, UK).

Stimulation

Drying and warming the baby provides adequate stimulation whilst preventing heat loss, but if this fails to generate a response then instigate resuscitation procedures (Biarent et al., 2005). Avoid more aggressive forms of stimulus: they are not a substitute for effective resuscitation.

Suction

There is no role for routine suctioning as it can delay ventilation, causes airway trauma and may lead to vagal-induced bradycardia (Resuscitation Council UK, 2005b). Consider it only if ventilation is unsuccessful.

The initial five breaths

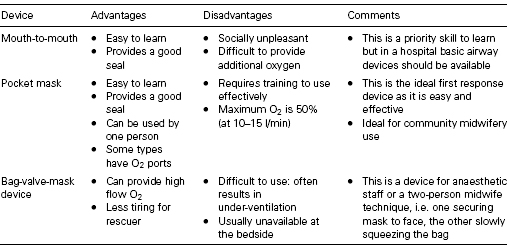

These ‘inflation breaths’ are designed to inflate and expand the lungs and remove amniotic fluid (Biarent et al., 2005). If delivered effectively, these vital initial breaths can restore spontaneous breathing. They are delivered slowly with constant pressure (maximum pressure <30 cm of water (Biarent et al., 2005)) held for 2–3 s. Do not deliver short, sharp, fast ventilations: this is ineffective and a common reason for failed initial resuscitation (see Table 17.1 for means of ventilation).

Table 17.1 Means of ventilation.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2007) recommends that the initial breaths should be administered using air. However, if the baby fails to respond despite effective inflation breaths, then supplementary oxygen should be provided. A centrally cyanosed baby with a heart rate >100 bpm who continues to ‘gasp’ will respond rapidly with stimulation and oxygen therapy (Zideman et al., 1998). Oxygen can be administered via a funnel, a facemask or a cupped hand over the baby’s face. It is important not to waft oxygen over the baby as this will actively cool it, and a bag-valve-mask (BVM) device should not be used to deliver oxygen to a spontaneously breathing baby as it increases respiratory workload (American Heart Association et al., 2000).

Following the initial breaths, reassess the baby. At this point the baby will either (a) have improved and be spontaneously breathing/crying, (b) remain apnoeic but with a heart rate >60 bpm or (c) be apnoeic with a heart rate <60 bpm.

Ventilation should continue at a faster rate of 30 breaths/min (allow 1 second for inspiration and 1 second for expiration). Commence cardiac compressions in all babies with a heart rate <60 bpm and reassess the baby every 30 seconds.

Table 17.2 Reasons for no response to assisted ventilation.

| Problem | Possible cause | Action |

| Poor technique |

|

|

| Chest not rising | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| ||

| Pressure release valve |

|

|

| activated (this valve |

| |

| reduces the risk of pulmonary barotrauma) |

|

N.B. Occasionally you may need to override the pressure relief valve by pressing on the valve (some BVMs have a clip for this purpose). However this is rarely required, especially with a 500 ml BVM.

Refer also to Fig. 17.1 for neonatal life support resuscitation algorithm and Table 17.2 for trouble-shooting technique when a baby does not respond to ventilation.

Ongoing neonatal resuscitation/complications

Compressions

International guidelines indicate that cardiac compressions should be commenced once effective ventilation has been instigated but the heart rate remains <60 bpm. The ratio of breaths to compression is set at 3:1 emphasising the importance of ventilation. It is difficult for the single-handed resuscitator to maintain an effective respiratory rate whilst also performing compression (Whyte et al., 1999; Biarent et al., 2005), so this process is improved by the presence of a second trained person. Although rarely required, endotracheal intubation facilitates asynchronised compression/ventilations, which improves coronary artery perfusion, but it should only be considered if a skilled intubator is available.

Cardiac compression technique

- Two-finger method. Place the tips of two overlaid fingers just below the nipple line in the centre of the baby’s chest. This is the preferred method for the lay public and the single-handed midwife.

- Two-thumb method. Encircle the baby’s chest with your hands, placing two overlaid thumbs just below the baby’s nipples in the centre of the chest. The two-thumb technique is the preferred method for resuscitating all babies <1 year old (Biarent et al., 2005).

All midwives should be able to perform both resuscitation techniques, as the two-thumb method is not suitable for single-person resuscitation.

The umbilical cord

It is routine practice to cut the umbilical cord immediately at delivery although Prendiville and Elbourne (2000) have demonstrated that delaying this process by at least 30 seconds can increase the transmission of maternal blood volume by up to 50%. Whilst NICE (2007) recommends immediate cord clamping as they cannot exclude a risk of hyperbilirubinaemia, it is worth speculating that an anaemic baby could potentially benefit from the extra blood. The umbilicus should be cut long >10 cm to facilitate cannulation.

Meconium aspiration

Suctioning the baby prior to delivery of the baby’s chest is ineffective and no longer recommended (Vain et al., 2004). Suctioning should only be considered in the apnoeic ‘flat baby’ where there is thick meconium obstructing the baby’s airway, although there is no evidence that even this prevents meconium aspiration (Resuscitation Council UK, 2005a).

Intubation

Intubation is rarely required (Palme-Kilander, 1992). It is a complex skill to learn and difficult to maintain. Therefore the emphasis is on effective BVM ventilation and not intubation. There are still a number of situations where intubation remains useful:

- Prolonged ventilation/difficult BVM ventilation.

- Surfactant administration.

- Special circumstances, e.g. diaphragmatic hernia.

The rarity of neonatal intubation reduces the opportunity for staff to maintain clinical skills. In circumstances where BVM ventilation is proving ineffective/impossible, a laryngeal mask airway has been successfully used (Esmail et al., 2002). Currently there is insufficient data to support the routine use of laryngeal mask airways during neonatal resuscitation (Biarent et al., 2005), but it is an interesting area for consideration for improving resuscitation/ventilation in units without access to experienced intubators.

Drugs

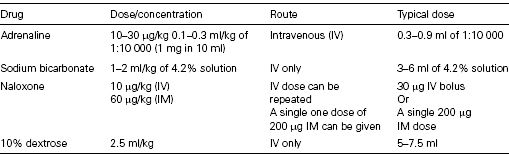

Drugs have a very limited role in neonatal resuscitation (see Table 17.3).

- Adrenaline is the main resuscitation drug for the neonate who, despite effective ventilation and cardiac compressions, has a heart rate <60 bpm (Biarent et al., 2005). Adrenaline should be administered intravenously (umbilical vein or cannula), although it can be administered via the intraosseous route. Administration via the endotracheal tube (ETT) is no longer recommended, but if this route is used higher doses are required (100 μg/kg) (Biarent et al., 2005).

Table 17.3 Neonatal resuscitation drugs.