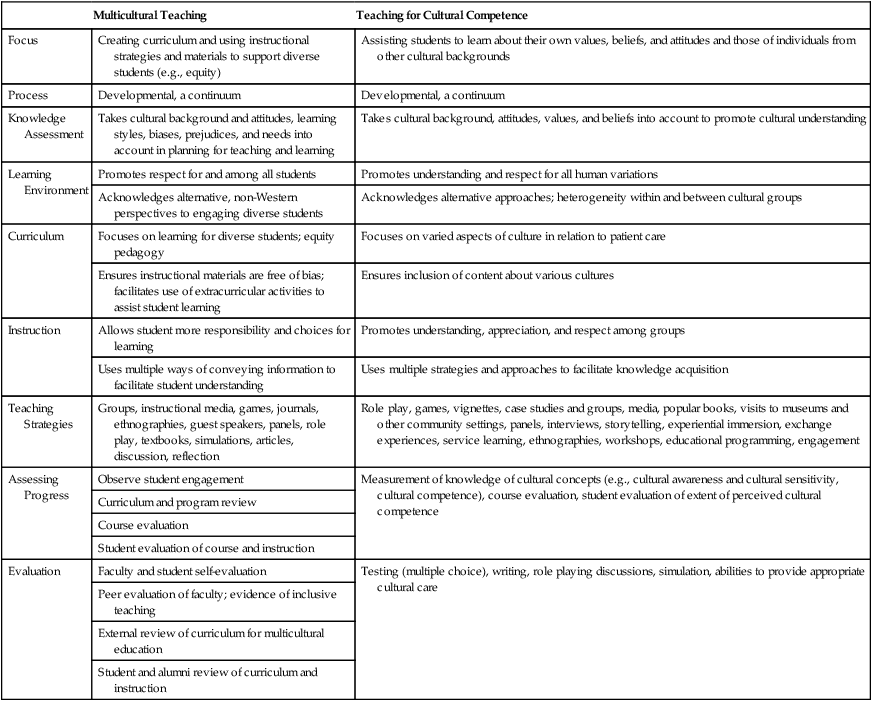

Lillian Gatlin Stokes, PhD, RN, FAAN and Natasha Flowers, PhD Significant changes are occurring in the population demographics in the United States, with shifts occurring in both ethnic and minority groups. In 2008, the Pew Research Center (http://pewsocialtrends.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/) projected that by 2050 about 20 per cent of the population will be immigrants or their U.S.- born decedents, and that the Latino population will comprise 29% of the populations. These changes are reflected in nursing schools as they attempt to recruit, enroll, and retain a student body reflective of the community in which the graduates will practice. Although the demographics of minority populations (white, non-Hispanic) fluctuates with periods of growth and decline (National League for Nursing, 2006), the numbers remain significant. Furthermore, diversity is noted in gender, age, culture, learning styles, and sexual orientation. The number of students whose second language is English is also increasing in nursing programs. In 2005 Asian nursing students were the largest group of English Language Learners (ELL) students enrolled in all combined basic registered nurse programs (5.6%) and highest in all baccalaureate programs (6%) (National League for Nursing, 2006). Increasingly, the literature is reporting the need to increase enrollment of students with disabilities because of the potential of enriching the profession (Marks, 2007). The nature of a global environment has implications for multicultural education as well. These increases in the diversity of the population and of nursing students have implications for teaching and learning in nursing. Faculty must develop curricula to accommodate diversity by choosing appropriate instructional materials, applying principles of multicultural education, and using teaching strategies to accommodate inclusivity in the classroom. Faculty must also acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes that will help to facilitate inclusive teaching as well as help students’ development of those skills needed for cultural competence so that patients will receive appropriate care. This chapter provides information about the theoretical foundations of multicultural education, recommends changes in course and curriculum development, offers suggestions for multicultural teaching and learning, and gives examples of instructional strategies and approaches essential to addressing diversity in the classroom. This chapter also includes information about useful strategies to facilitate the development of cultural competence in students. Multicultural education shares the same premise of addressing student learning outcomes and success as cultural competence does in addressing health disparities. Table 17-1 describes the differences between these two concepts. Multicultural education has challenged educators and educational administrators to consider equality and inclusion for the benefit of all students. The father of multicultural education, James A. Banks, defines it as “an idea, an educational reform movement, and a process whose major goal is to change the structure of educational institutions so that male and female students, exceptional students, and students who are members of diverse racial, ethnic, language, and cultural groups will have an equal chance to achieve academically in school” (Banks & Banks, 2004, p. 32). With this three-pronged notion of multicultural education, Banks and Banks (2004) provide a wide lens for any educator or educational administrator to understand the critical need to situate the student at the core of any inclusive, engaging learning situation. TABLE 17-1 Multicultural Teaching and Teaching for Cultural Competence In an effort to bring critical attention and solutions to “ideological resistance, lack of teacher knowledge of ethnic groups, and the heavy reliance of teachers on textbooks” (Banks & Banks, 1993, p. 212), Banks outlined and widely shared his Levels of Integration of Multicultural Content. Although Banks accepted that the levels could be mixed and blended in varied teaching situations, his model clearly serves as a four-level developmental approach: (1) contributions, (2) additive, (3) transformative, and (4) social action. These levels range from the initial integration of cultural artifacts and mainstream heroes of particular ethnic groups in the contributions level to the social action level where “students make decisions on important social issues and take actions to help solve them” (Banks & Banks, 1993, p. 199). Banks’ Levels of Integration represent one approach to content transformation and echoes the historic battle for ethnic studies that began in the late 1960s and early 1970s when higher education began questioning and embracing the need for diverse cultural content in colleges and universities (Duarte & Smith, 2000). In addition to his developmental model, Banks (2007) outlined what he called the five dimensions of multicultural education. These dimensions include content integration, knowledge construction, equity pedagogy, prejudice reduction, and empowering school culture and social structure. While not developmental, these five critical components of multicultural education emphasize planning and action steps in empowering cultural groups in the classroom setting. Higher education has benefited from theorists such as Banks as they began to familiarize prospective and current teachers in the K through 12 educational system and slowly hold them accountable for the retention of the growing diversity among college students. Beyond the teacher education programs, notions of multicultural education can be cited in other professional programs such as business, social work, and (not surprisingly) medicine and health sciences. Marchesani and Adams (1992) designed the framework Four Dynamics of Multicultural Teaching to shape faculty development in this area. Current faculty development scholars such as Stanley, Saunders, and Hart (2005) highlight this four-dimensional framework as a step toward faculty reflection and attention to the needs of students from diverse backgrounds. More specifically, Stanley and other colleagues suggest examining the implicit messages embedded within classroom norms and the explicit messages that are found in the curriculum (Stanley et al., 2005). Along with reflection on curriculum and instruction, the Four Dynamics of Multicultural Teaching (Marchesani & Adams, 1992) emphasize faculty understanding of their own biases as well as their students’ beliefs and biases. By doing this, faculty begin to transform their courses to better support the diversity that exists within the classroom and the course content. To reach multiple disciplines with the same goal to support all learners, special education scholars Margie Kitano and Ann Morey created a resource for academics in higher education (Morey & Kitano, 1997). In addition to gathering the practice and wisdom of professors in areas such as nursing, economics, biology, English as a new language, and mathematics, Kitano developed the Paradigm for Multicultural Course Transformation (Morey & Kitano, 1997). Seemingly untested by the scholars in the faculty development field, this theory effectively charts the benefits of understanding the principles of learning and multicultural education as the first step to multicultural course transformation. Among the three levels Kitano proposes, the third and final transformed level is ideally where students are learning from the nondominant or non-Western perspectives, which are treated as part of the content of the course, and students reflect on their own learning (and not just the letter grade or point). Also, in a transformed curriculum the culture of the classroom is open to dialogue where there is a “challenging of biased views and sharing of diverse perspectives while respecting rules established for group process” (Morey & Kitano, 1997, p. 24). It is important to note that Kitano structures a paradigm that includes more than just a snapshot of what happens in the exclusive, inclusive, and transformed levels. Faculty must consider the four major course components: content, instructional strategies, assessment of student knowledge, and classroom dynamics. Therefore a thorough course analysis is assumed to be a significant component of multicultural course transformation. Within a thorough course analysis, Morey and Kitano (1997) propose that the multicultural goals help determine the level of course change and the course elements requiring modification. The modification itself can present in various ways. A first step is to identify the expected outcomes, such as what is expected to be achieved. For example, after articulating that one goal for a course is to increase knowledge of bias and ethnocentrism as it relates to the study of various cultural groups, a faculty member may determine that the course’s content includes various examples of cultural groups. However, the course may not facilitate opportunities for open and equitable exchanges of ideas and values. Therefore the transformative work may begin in the area of instruction for classroom as well as clinical practice. The ongoing dialogue about multicultural education in higher education does include outcomes from curricular reform and instructional practices. Major studies from 2000 to the present significantly outline the benefits of diversity. In 2000 three research studies on diversity in college classrooms by the American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors rejuvenated this dialogue and pointed to particular challenges and benefits to diversifying the curriculum. The findings are based on (1) the analyses of data from more than 570 faculty members using the Faculty Classroom Diversity Questionnaire, (2) analyses of data from a similar survey of 81 faculty members at one college in the Midwest, and (3) an in-depth, qualitative multiple case study of three interactive multiracial and multiethnic classrooms at a university in the eastern United States. The use of case studies by both faculty members and students revealed that the perspectives of racially and ethnically diverse students generated more complex thinking among all students. In addition, students also shared that classroom diversity is important in subjects such as math, science, and accounting because “biases can be challenged and exposed” (American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors, 2000, p. 7). When asked to rate their comfort level in teaching racially and ethnically diverse classes, 86% of faculty members responded with 4 or 5 on a scale of 1 (not comfortable) to 5 (very comfortable). Although 71% indicated that they felt well prepared to teach in such a setting, only a small portion of this group admitted to initiating discussions of race in class (36%) or assigning students to diverse groups (33%). Even with a sense of preparedness, faculty did not report innovative, interactive strategies to make the most of their diverse classes. These data beg the question of faculty involvement in diversifying the curriculum, which was carefully investigated in Helton’s (2000) quantitative research study and “involved” faculty who had participated in the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ initiative, American Commitments: Diversity, Democracy, and Liberal Learning. Among the 63% who responded to the questionnaire, 92% of the faculty identified the following items as “somewhat” or “extensive” in motivating their participation in diversity initiatives: • Students who represent racial, gender, or sexual diversity need to see themselves in the curriculum. • Pursuit of the whole truth requires expansion and inclusion of other points of view. • The desire to add new research findings and knowledge to courses and programs. • Participating in diversity initiatives is the morally or ethically compelling thing to do. • I feel a bond with students of marginalized groups. • Students who represent racial, gender, or sexual diversity need to see themselves in the curriculum. • Wanting to meet the learning needs of all of my students. • I want to add new research findings and knowledge to my courses and programs. • Diversity is an intellectually stimulating, new, and challenging arena for me. The five perceived benefits from faculty involvement in this study were intellectual challenge (95%), teaching satisfaction (89%), opportunity to influence social change (88%), teaching effectiveness (85%), and student interaction (84%) (Helton, 2000). Studies that focused on students shared positive findings. In Chang’s (2002) study, 112 undergraduates who were completing a diversity course reported less prejudice in comparison to 85 students who had just started taking the course. Smith, Parr, Woods, Bauer, and Abraham (2010) found that roughly three courses that dealt with globalization, inequities, race, class, and gender issues affected 156 graduates’ perceptions of multicultural competence and volunteer service. Increased levels of self-reported multicultural competence positively correlated with undergraduate courses with diversity-related content. Findings such as these point to the benefits of diversity courses and the inclusion of multicultural content in the curriculum. One of the first ways to initiate a multicultural education is to review the curriculum for its responsiveness to student diversity. Different approaches have been identified. For example, Morey and Kitano (1997) identified three levels of change in transforming any course: (1) exclusive, (2) inclusive, and (3) transformed. The exclusive level encompasses traditional and mainstream experiences and perspectives. When information is presented in a didactic manner, there is limited discussion and knowledge acquisition is assessed through written examinations. An inclusive level involves the addition of alternative perspectives to traditional views. There is support for the use of a variety of methods of teaching to facilitate active learning. To provide rich experiences for students, the emphasis should be placed on the transformed curriculum. In a transformed curriculum, the structure is changed to facilitate students to view concepts, issues, and content from a variety of ethnic cultural perspectives (Byrne, Weddle, Davis, & McGinnis, 2003). The desired outcome is significant change—not so much in what is taught, but in how it is taught (Morey & Kitano, 1997). A comparative review of the two models, Morey and Kitano (1997) and Banks (2006), reveals components that are useful for multicultural education. Emphasis in the former model is on transformation and overall structural changes. The usefulness of the latter model is its distinct identification of dimensions that can serve as a template for changes in curriculum. The intention of the dimensions in the framework affords opportunities to build on previous dimensions as students progress through the nursing program (Bagnardi, Bryant, & Colin, 2009). These are but two examples. Faculty can explore additional frameworks with the goal of an ultimate outcome of inclusion and integration of multicultural content into the curriculum, thus facilitating multicultural education. Diverse cultural content must be integrated throughout the curriculum. The multicultural model designed by Banks (2004, 2006) is described as a model that can be adapted to all levels of the curriculum. Bagnardi et al. (2009) describe an experience of integrating Banks’ model throughout an undergraduate curriculum. Students should learn to apply various nondominant perspectives (Morey & Kitano, 1997). As Banks suggested, instructors must move beyond the initial level of integrating cultural artifacts such as names and holidays to an integrative level where students obtain more substantive information about cultural groups (Banks & Banks, 1993, 2004). Educators should make concerted efforts to exhibit attitudes of positive portrayal of diversity and indicate that diversity is valued. Exposing students to various cultural norms, health beliefs, and practices is a feasible first step in diversifying the curriculum. Underwood (2006) used an inquiry approach to facilitate enhanced knowledge and sensitivity related to culture and health. A student assignment was to write three questions about an ethnic group of the student’s choice. The themes that emerged from these questions were used to structure the course. Also, students should have assignments that provide opportunities for them to reflect on all aspects of culture: language, communication patterns, family relationships, religion, spirituality, and ethnicities (e.g., Native Americans, Hispanics, Asian Americans, African Americans, Arab Americans). Students should specifically have access to information about groups that are dominant within the areas in which they learn and practice their clinical skills. The content should excite and motivate students to actively facilitate change in communities. The latter represents applications of the social action element previously described. Immersion experiences can occur in several ways. One is through the use of ethnographies. Ethnography refers to a written presentation of qualitative descriptions of human social information based on fieldwork. Brennan and Schulze (2004) engaged students in reading an ethnography. The activity was followed by a written assignment of an analysis of the reading. Presentations and discussions of the analysis were made in groups. Results of the ethnographic analyses indicated that students were immersed in the culture. Group discussion of the analyses was beneficial in providing a multicultural experience for all participants. Experiences can also occur through spending time and engaging with specific cultural groups within the United States (e.g., special populations) and abroad. Immersion is useful not only for teaching and learning, but to facilitate the development of cultural competence as well. Caffrey, Neander, Markle, and Stewart (2005) conducted a study to evaluate the effect of integrating cultural content in an undergraduate curriculum on students’ self-perceived cultural competence and to determine whether a 5-week clinical immersion in international nursing had additional effects on students’ self-perceived cultural competence. The results of the study revealed a larger gain of self-perceived cultural competence for students who engaged in the immersion experience. To facilitate inclusivity, faculty should consult resources that are focused on teaching and learning in classroom environments. In Multicultural Teaching in the University, Schoem, Frankel, Zuniga, and Lewis (1995) provide specific information related to a variety of teaching–learning strategies. There are excellent texts that provide tips and a variety of ways in which the strategies can be implemented. From these, faculty can acquire information about how to teach students about different cultures. Ukoha (2004) calls for the acquisition of theoretical bases for these. Morrison, Sullivan, Murray, and Jolly (1999) designed an instrument to address the evidence base of instructional strategies. Faculty could use these or similar designs to evaluate their instructional effectiveness. Refer to Table 17-2 for a list of online resources for multicultural education (and cultural competence). TABLE 17-2 Online Resources for Multicultural Education and Cultural Competence As attention is given to making curricular and content changes, opportunities must also be provided for clinical practice and engagement so that knowledge is reinforced, skills are developed, and changes occur in attitudes. In designing instruction for multicultural teaching and learning, a variety of instructional methods and materials must be used to support active teaching and learning. In other words, in the classroom faculty must move from lectures to activity and variety, such as the use of case studies, role play, games, drama, films, movies, panels; students’ engagement in interviews, assigned readings, writing specific papers, discussions questions; and involvement in real-life experiences. One experience can be service learning with agencies that service culturally diverse patients (O’Grady, 2000) or those that have a specific patient population (see also Chapter 12). The benefits of such experiences are multifaceted (Hunt, 2007). Immersion experiences in specific areas can also serve to engage students. Closely aligned with engagement experiences, attention must also be given to instructional strategies that are used in the classroom, in clinical practice, and online. Morey and Kitano (1997) suggest that faculty create learning activities to promote reflection among students. The opportunities are many. Faculty can engage students by designing written assignments, such as journaling logs or learning diaries (Anderson, 2004; Billings, 2006; Craft, 2005) and personal letters written by and for the student, which can be a precursor to reflection papers. Letters can have a dual purpose of initially addressing personal fears, feelings, assumptions, and expectations about a planned experience or about different racial and ethnic or age groups, and later reflecting on the identified written content in preparation for writing a major paper. The connecting link between the initial letter and the reflection could be an experience such as service learning. Students can read the letters after the experience and reflect on the initial letter in terms of similarities to and differences from their previous thoughts, feelings, and assumptions, thus providing an avenue for deeper reflection, meanings, and considerable learning. The letter strategy, used for 5 years in a course for beginning students, resulted in noted improvement in the quality and specificity of papers and enhanced learning as identified by students (Stokes, Linde, & Zimmerman, 2008). Immersion and service-learning experiences (see Chapter 12) afford opportunities for reflection as well. Activities relating to cultural diversity can also be resources for framing instructional strategies (Eliason & Macy, 1992). Not only should emphasis be placed on inclusive teaching (and learning) in classroom settings but in clinical practice settings as well (Millon-Underwood, 1992). Millon-Underwood (1992) suggests that experiences be planned to align with the nature of the community and that faculty make efforts to ensure that one in every five patients selected for student clinical learning experiences is from a diverse cultural group. To assure the reality of this, systems such as clinical experience checklists or databases can be established for students and faculty to monitor and track the gender, age, racial and ethnic makeup, and socioeconomic status of patients assigned for care. This system and the rationale for its use should be shared with students. The use of the online technology can be an avenue for promoting multicultural education. Merryfield (2001) reported results of an online interaction experience indicating that teachers were open, frank, expansive, curious, and confessional in their willingness to share and discuss certain issues and that interaction patterns were more equitable and cross-cultural than the campus-based course. This methodology also has the potential for linking classrooms for the purpose of cultural exchanges, for example, through the use of virtual experiences. Additionally, faculty teaching online courses can facilitate students’ awareness of their own beliefs and those of others by posing questions that require students to reflect on their values, beliefs, or culture and contrast them with those of other members in the class (Flowers, 2002). Online surveys and journals are two strategies for prompting these discussions.

Multicultural education in nursing

Multicultural teaching and learning

Components of multicultural education

Multicultural Teaching

Teaching for Cultural Competence

Focus

Creating curriculum and using instructional strategies and materials to support diverse students (e.g., equity)

Assisting students to learn about their own values, beliefs, and attitudes and those of individuals from other cultural backgrounds

Process

Developmental, a continuum

Developmental, a continuum

Knowledge Assessment

Takes cultural background and attitudes, learning styles, biases, prejudices, and needs into account in planning for teaching and learning

Takes cultural background, attitudes, values, and beliefs into account to promote cultural understanding

Learning Environment

Promotes respect for and among all students

Promotes understanding and respect for all human variations

Acknowledges alternative, non-Western perspectives to engaging diverse students

Acknowledges alternative approaches; heterogeneity within and between cultural groups

Curriculum

Focuses on learning for diverse students; equity pedagogy

Focuses on varied aspects of culture in relation to patient care

Ensures instructional materials are free of bias; facilitates use of extracurricular activities to assist student learning

Ensures inclusion of content about various cultures

Instruction

Allows student more responsibility and choices for learning

Promotes understanding, appreciation, and respect among groups

Uses multiple ways of conveying information to facilitate student understanding

Uses multiple strategies and approaches to facilitate knowledge acquisition

Teaching Strategies

Groups, instructional media, games, journals, ethnographies, guest speakers, panels, role play, textbooks, simulations, articles, discussion, reflection

Role play, games, vignettes, case studies and groups, media, popular books, visits to museums and other community settings, panels, interviews, storytelling, experiential immersion, exchange experiences, service learning, ethnographies, workshops, educational programming, engagement

Assessing Progress

Observe student engagement

Measurement of knowledge of cultural concepts (e.g., cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity, cultural competence), course evaluation, student evaluation of extent of perceived cultural competence

Curriculum and program review

Course evaluation

Student evaluation of course and instruction

Evaluation

Faculty and student self-evaluation

Testing (multiple choice), writing, role playing discussions, simulation, abilities to provide appropriate cultural care

Peer evaluation of faculty; evidence of inclusive teaching

External review of curriculum for multicultural education

Student and alumni review of curriculum and instruction

Theoretical frameworks

Research on multicultural education

The curriculum and multicultural education

Integrating multicultural content into the curriculum

Inclusive teaching: strategies and approaches

http://www.diversityweb.org

Association of American Colleges and Universities provides research, classroom practice, and university diversity reform information

http://edchange.org

Resources for diversity assessment, professional development, and research

http://www.tcns.org

Transcultural Nursing Society website with access to TCN certification, professional journal, and membership

http://www.hrsa.gov/culturalcompetence/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides assessment tools, research, and toolkits for the cultural competence of health care providers

http://ctl.iupui.edu/TSSS_modules/inclusive/introduction/1.htm

The Center for Teaching and Learning at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis offers modules to support multicultural teaching and learning in higher education

http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/

The Center for Teaching and Learning at University of Minnesota offers resources for classroom teaching and for supporting non-native speakers of English

Classroom

Clinical practice

Online courses

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree