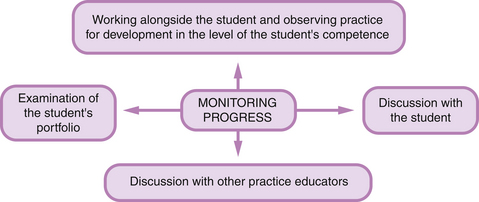

Chapter 7 Observation of practice for developing levels of competence Criteria for assessing development in the novice, advanced beginner and competent levels of performance Levels of supervision and support Examination of the student’s portfolio of learning Managing some assessment problems Students experiencing problems learning during clinical practice: the unsafe student Managing the situation when a student has to be failed Monitoring progress, managing feedback and making assessment decisions are interrelated activities that are integral to the continuous assessment of practice. These activities are central to and essential in helping students learn through their practice to develop clinical competence. Using the continuous assessment process enables the monitoring of progress continually and the giving of feedback informally and constantly as the learner works alongside the practice educator – even over one working shift, feedback is an activity that occurs many times. There are, however, specific times when formal feedback should be given based on a more detailed examination of progress. As discussed in Chapter 6, when pre-scheduled and pre-planned ‘formal’ formative and summative assessments are conducted, time and opportunities are available to discuss progress with the student, formally give feedback and make assessment decisions based on the analysis of assessment evidence. The practice educator is in a ‘unique position in being able to provide precise feedback to individual students on all aspects of practical professional development’ (Stengelhofen 1993:153). However, if assessment is to be a true learning process, the student should be an equal partner in these activities – progress is monitored jointly through the formative assessment process set up, and the student participates actively during feedback and assessment decision-making sessions. It is important that these activities occur, not only to maintain the integrity of the assessment process itself but also to meet the rights of the student as a learner. Torrance & Pryor (1998) believe that assessment is truly formative only if it involves the student directly in self-assessment. ‘Managing feedback’ is used in this chapter to signify the activity of holding constructive discussions with the student about clinical experiences that the student and the practice educator have been involved in. Feedback can take place informally as the practice educator works alongside the student, or more formally during pre-arranged feedback sessions. Rowntree (1987:24) considers that this essential learning activity is the ‘life-blood of learning’. There is research evidence that suggests that this ‘life-blood’ is not well sustained – feedback is either not done well or as frequently as needed or, worse still, not at all (Figure 7.1) (Fitzgerald et al 2010, Clynes & Raftery 2008, Neary 2000, Fish & Twinn 1997, Bedford et al 1993). Bedford et al (1993:107) quoted one practice educator on assessment feedback: As noted in Chapter 6, it is knowledge of the results of performance provided by detailed factual constructive feedback that enables students ‘to monitor strengths and weaknesses of their performances, so that aspects associated with success or high quality can be recognized and reinforced, and unsatisfactory aspects can be modified or improved’ (Sadler 1989:120). Feedback therefore contributes directly to learning through the process of formative assessment. Constructive feedback not only has an impact on the teaching/learning process but also gives messages to students about their effectiveness and worth – their self-esteem (Gipps 1994). Feedback therefore has an indirect effect on learning by how the academic self-esteem of the student is affected. Coopersmith (1967 in, Gipps 1994:132) defined self-esteem as: A major determinant of self-esteem is feedback from significant others. Consequently, students look to, and indeed expect and welcome, constructive feedback from significant others such as their teachers and assessors (Embo et al 2010, Neary 2000, Phillips et al 2000, Gipps 1994, Bedford et al 1993). Other authors found that students view good clinical experiences to include receiving constructive feedback (Kotzabassaki et al 1997, Bedford et al 1993, Neville & French 1991). What we know about the effects of assessment on motivation tells us that students give up trying if they do not see themselves as capable of success. If they feel relatively worthless and ineffectual they will reduce their effort or give up altogether when work is difficult (Child 1997). On the other hand, people who hold positive self-perceptions usually try harder and persist longer when faced with difficult or challenging tasks. The following framework is suggested for managing feedback sessions: • timing of the feedback session • involving the student in self-assessment • using some ‘rules of thumb’ for managing constructive feedback. Feedback will have maximal motivational impact on learning if it takes place while it is still recent and therefore still relevant: points and issues raised are therefore more meaningful and alive (Bailey 1998, Gipps 1994); furthermore, the event and its details are fresh and accessible to memory and not distorted with time (Jones 1995). In the clinical setting, if appropriate, this could take place as a running commentary whilst the learner is performing, or as soon as possible after the event. These are used to offer feedback on aspects of practice that are observed by the practice educator. Such opportunistic feedback will thus be situation specific, which ensures that important elements are included. In addition, this lends itself to discussions and demonstrations of how theory is related to practice. Feedback sessions after the event will be more beneficial if the practice educator takes the responsibility for making time available and arranging a suitable venue (Gomez et al 1998). It will not be conducive for engaging in constructive feedback if either the practice educator or the student is still preoccupied with activities on the ward or after a busy clinical shift. The session could then prove to be counterproductive. It is important to remember that feedback must be timely to give the student enough time and opportunities to improve. The format can be oral or written or both. Students usually look for both. Fish & Twinn (1997) believe that written notes are essential in providing continuity in the monitoring of progress. When written notes are kept, the valuable details of the situation are not forgotten, which increases the potential for learning (Bailey 1998). Within the continuous assessment process of pre-registration of health care students, written records of sessions reviewing progress are generally required. Constructive feedback sessions may be used to review progress formally and written records kept of these sessions. The importance of asking for the student’s self-assessment before giving feedback cannot be underestimated as it provides the practice educator valuable insight into the student’s own perceptions of performance and learning that had taken place. The process of delivering constructive feedback is considerably easier when personal practice limitations are identified by the student. There is more detailed discussion on student self-assessment in the sections on formative assessment in Chapter 6, and the section ‘Discussion with the student’ below. It is essential that constructive feedback is managed systematically and with discipline. The following rules of thumb for the management of constructive feedback are based upon and extended from the work of Bailey (1998), Fish & Twinn (1997) and Paul (1988): • Prepare for the session remembering that feedback should not occur in a vacuum but on the basis of explicit aims or objectives of the placement (Billings 2010). When you need to engage in constructive feedback with another person, it generally means that there is some aspect of the person’s performance or behaviour that you perceive is a problem and that you wish the person to correct (Paul 1988). You need to think carefully about what you want the outcome to be; this means that you need to be able to specify exactly what you want the other person to do or to stop doing. If you cannot do this, do not attempt the session as it means that you are not clear enough about what the problem is. You then run the risk of ending up making generalized statements, which frequently offend. • Keep your appointment with the student and give him/her your undivided time, attention and interest – do not look at your watch constantly. Allocate sufficient time. • Use a quiet venue and maintain privacy. Be careful not to be interrupted or distracted. • Do not tackle too many things at once – try to foster a sense of progress. Gipps (1994) says that the most effective forms of feedback are those that focus students’ attention on their progress in mastering the required performance. This emphasis tends to enhance self-efficacy and encourages effort attribution. • Always try to make the session a learning situation for the student. Be positive as a first step. Just as important as identifying areas of weakness is identifying areas of relative strength. Temper negative comments with praise – the so-called ‘praise sandwich’ (Hinchliff 2004). Rowntree (1987:45) quoted the pioneering chemist Sir Humphrey Davy, who wrote of ‘the love of praise that never, never dies’. Students tend to remember the negative rather than the positive – good points therefore need reinforcing. Help the student to see negative comments as points for growth. • Use evidence from episodes of practice in as objective a way as possible. Stick to facts and present them in as neutral a way as possible. Use any written evidence from the student’s portfolio to provoke discussion. • Avoid generalizing and making subjective comments. A statement such as ‘you were brilliant’ may be pleasant to hear, but does not give any detail to be useful as a source of learning. Try to pinpoint what the student did that led you to use the label ‘brilliant’. Praise effort and strategic behaviours and focus students on learning goals; this will lead to higher achievement than praising ability or intelligence, which can result in a learned-helplessness orientation (Nicol & McFarlane-Dick 2005). However, the praise must fit the achievement; overzealous praise may cause embarrassment or be considered insincere. • Do not compare with other students. • Above all, remember that criticism is usually counterproductive. • Be clear about your role – that of being an assessor giving constructive feedback on practice. It is your responsibility to establish communication, clarify any problems and either get a commitment for change or offer a solution (Paul 1988). Establish communication (Figure 7.2): • Use positive and warm non-verbal communication. Smile. Make eye contact. Do not be confrontational. • Listen to the student. Get the comments and ideas from the student. Asking makes the student feel valued and is better than telling. You may become aware of facts and circumstances that you were not aware of; these may cause you to change your mind about the problem or the nature of the problem. • Work with the student not on her or him. Avoid a power struggle. Do not take control of the situation. • Giving negative feedback or leading the student to focus on the things that did not work is also important and should not be avoided. It is tempting to avoid unsatisfactory work, but performance will not improve without knowledge of what was wrong. Remember that there will come a time when it may be too late to give negative feedback. • Use open-ended questions and give reasons for your questions and comments. • Encourage frankness and share worries and uncertainties – we are all learners. Remember that feedback works best when a climate of trust exists between the giver and receiver. • Always take account of as many dimensions of the practice situation as possible. Try not to be biased by your own strong reaction or views about any individual part of the situation as this might colour the feedback session. • If the student counterattacks, do not rise! Try to see it from the student’s point of view – take account of the student’s prior experiences, interpretations and perceptions of what has happened. Explore and clarify what the student is saying. • Be prepared to see that your own and perhaps different value-base and skills are only of indirect importance. You are not trying to cast the student into a mould of yourself but rather, within professional parameters, to help the student be more fully herself or himself. • Once you have a clear picture, state the problem in specific terms. Focus on behaviour and facts and not on opinions, personalities and generalities (Paul 1988). For example, instead of saying ‘I wish you’d do something about the way you respond to patients, you do not seem to care’, state the facts and behaviours: ‘Yesterday, I noticed that Mrs Bell had to press her buzzer three times over 15 minutes before you got up from the nurses’ station to respond to her. Today, when you were talking to Mr Hunt you did not make any eye contact and I thought you gave an abrupt answer when he asked you a question. You were also frowning all the time.’ Get a commitment for change or offer a solution: • Ask the student how performance can be improved. The only way to tell if there is learning consequent to feedback is for students to make some kind of response to complete the feedback loop (Sadler 1989). Unless students are able to use feedback to produce improved work (to improve upon a similar/same aspect of care), neither they nor those giving feedback will know that it has been effective. • You may need to show how performance can be improved. Be specific: offer alternatives. Avoid suggesting that there are simple right answers. Suggest a small new target that will lead to success. • Make sure the student understands what is expected by asking the student to say what she/he will aim for and what first steps will be taken. Without this commitment, there is the possibility that nothing will happen. • You may wish to make a written agreement with the student in the form of an action plan. Within this, set clear targets for the next period of supervised practice. Readers are directed to the training package by Paul (1988) for some more information on how to give and receive constructive criticism. Monitoring the progress of students is an essential part of the continuous assessment process. Progress can be monitored most accurately if there is continuity of supervision by the same practice educator. The same practice educator is better placed for keeping abreast of the clinical activities the student has had and will therefore know the amount of learning the student has achieved and how the competence of the student is developing. Monitoring progress is an ongoing assessment activity and takes place throughout the duration of the student’s placement. Monitoring in this context, and not ‘policing’, is viewed as a process to help student learning, development and progression. We need to keep track of whether the student is developing competence and achieving the statutory competencies for professional practice. We therefore need to consider carefully what the student is learning, the clinical activities the student has been participating in and how further learning can be facilitated. When monitoring the progress of the student it is important to consider the prior clinical experiences of the student, the competencies and learning outcomes that the student needs to achieve during the placement and the stage of training the student is at. Curriculum documents will frequently state the expected level of performance at a specified stage of training. • What has the student done and learned so far? How will I know? • Is the student having any difficulties? How will I know? • What can be done to facilitate further learning and development? To obtain answers to these questions, the assessment activities shown in Figure 7.3 are suggested. In Chapter 4 there is a detailed discussion of how observation may be used as a method of assessment to obtain direct evidence of the ability to perform care activities. When monitoring the progress of students during observation of their practice, the practice educator needs to gather evidence of: • continuing safe and accurate performance of care activities with increasing speed and dexterity as the student engages in more clinical experiences and gains confidence • the development in the level of a student’s competence from the outset of a placement and at its conclusion (Bedford et al 1993). What we know about the nature of expertise tells us that there are well-defined characteristics, across domains, that differentiate the performances of experts from novices (Benner et al 1996, Glaser 1990, Benner 1984). Glaser (1990:477) sums up the situation thus: Glaser puts forward the case that, with growing proficiency, the changes in a person’s cognitive ability and psychomotor performance can define criteria by which competence can be assessed. The Dreyfus model (in Benner 1984) considers that, in the acquisition and development of a skill, a learner passes through five levels of proficiency: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert. As a learner passes through these levels, there are corresponding changes in three general aspects of performance. First, there is a move away from reliance on rules and principles to the use of past experience to guide practice. Secondly, the learner begins to see a situation less and less as a combination of equally relevant bits and more and more as a complete whole in which only certain parts are relevant. Thirdly, the learner becomes an involved performer and engages in the situation. Benner et al (1996) and Benner (1984) applied the Dreyfus model to the study of skills acquisition in the practice of qualified nurses. They are careful in stating that skills in the nursing context refer exclusively to skilled nursing interventions and clinical judgement skills in actual clinical situations and not to psychomotor skills or to other skills learnt in the laboratory setting. For the purposes of this discussion, a summary of the performance characteristics from the work of Benner et al (1996) and Benner (1984) at the levels of development of the novice, advanced beginner and competent will be made here. Although these characteristics are derived from the performance of qualified nurses, it is my view that they can be extrapolated to the developing performance of pre-registration students. Following this exposition, the characteristics of the knowledge base with increasing proficiency described by Glaser (1990) are summarized. • Students enter a new clinical area as novices with no experience of the situations in which they are expected to perform. • They must be given rules and explicit detailed instructions to guide their performance; procedural lists are important for successful performance. • They focus on getting individual tasks done; novices generally do not see beyond the task at hand and may not recognize underlying problems of the patient. • They have little understanding of how to use classroom-acquired theory to guide practice. • The advanced beginner can demonstrate marginally acceptable performance. • As a result of prior experiences, they are able to identify the recurring components of situations, but are unable yet to sort out what is most important. • They cannot order information into a meaningful whole. • Their concern for good care is almost exclusively related to physical and technological support and to completing all the ordered treatment and procedures. • increased clinical understanding and are able to focus on the clinical condition and management of the ‘whole’ client/patient and less on getting tasks done • increased technical skill – performance is more fluid and coordinated and they can predict the outcomes of their performance • more accuracy at judging the difficulty of a task • increased ability to handle busy complex situations and they can make decisions and solve problems • improved time management skills • improved organizational ability – they can prioritize care and manage care for several patients • increased awareness of the appropriateness of their actions and are able to ask questions about what they have to do to improve their level of competence. Glaser (1990) notes that, as competence in a domain grows, the person displays a knowledge base that is increasingly coherent and useful. The characteristics underpinning these descriptors are described briefly here. The following criteria for assessing the development in the level of a student’s competence are based upon, and extended from, the work of Benner et al (1996), Glaser (1990), and Benner (1984). When using these criteria to assess the level of performance and monitor progress, it is important to remember that the change from the novice level to competent level is incremental (Benner et al 1996) and on a continuum. The criteria below have been developed to reflect this. • Requires very detailed and explicit instructions. • Requires less detailed and explicit instructions. • Requires some detailed and explicit instructions. • Performs some activities with few prompts. • Performs regularly practised activities with few prompts. • Performs regularly practised activities in a fully integrated way. • Beginning to assess, plan and implement care. • Within level of practice, responds appropriately in situations requiring urgency. It is important for each clinical area to identify those activities in which the student is expected to be able to achieve competence. The reader is directed to the discussion of ‘competence’ in Chapter 3. • Performs activities with few prompts. • Performs regularly practised activities in a fully integrated way. • Leads regularly practised activities with few prompts. • Beginning to prioritize care. • Able to assess, plan and implement care. • Beginning to evaluate effectiveness of care. • Beginning to involve clients in their care. • Within level of practice, responds appropriately in situations requiring urgency. • Performs most activities in a fully integrated way, without prompting. • Able to assess, plan and implement care. • Able to evaluate effectiveness of care and make changes to care plans. • Able to plan, prioritize and manage care for a group of clients within a time span. • Actively involves clients in their care. • Within level of practice, responds appropriately in situations requiring urgency. • Critiques evidence-based research and its implementation. • Able to make connections between complex chunks of theory. During the early stages of a pre-registration programme, a student who is new to a clinical area is likely to start practice at the novice level, but may achieve competent practice in some aspects of care by the end of the placement. The rate of progression is dependent on many factors, such as opportunities for practice and debriefing and reflection with the practice educator, the prior experience of the student, the student as a learner and so on. In each new clinical area the ‘junior’ student may perform at novice level for a longer period before advancing. The ‘senior’ student who may have been to similar clinical areas, however, would be able to, and indeed would be expected to, move more rapidly to advanced beginner and competent level practice. The practice educator is reminded that it is a requirement of pre-registration education to prepare students to be able to apply knowledge, understanding and skills to perform to the standards required in employment when registered and practice is safe and effective. It is suggested here that the ability to perform at the competent level is the required level to enable the student to achieve the requirements of statutory training, and to enable her/him to make the transition to registered practitioner. The criteria for assessing competent level practice should thus be used when monitoring the progress and assessing the practice of students who are at the stage of being prepared for professional practice (e.g. in the last 6 months of training). This period of practice will assist the student to start to make the transition from student to registered practitioner.

Monitoring progress, managing feedback and making assessment decisions

Introduction

Managing feedback

Managing feedback sessions

Timing of the feedback session

Format of the session

Involving the student in self-assessment

Using some ‘rules of thumb’ for managing constructive feedback

Monitoring progress

Observation of practice for developing levels of competence

The novice

The advanced beginner

Competent

Knowledge base

Criteria for assessing development in the novice, advanced beginner and competent levels of performance

Novice level

Advanced beginner level

Competent level

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access