On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the effects of impaired mobility on general function and quality of life. • Describe age-related changes in bones, joints, and muscles that may predispose older adults to limitations in mobility. • Discuss risk factors for impaired mobility. • Describe the beneficial effects of exercise and appropriate exercise regimens for older adults. • Discuss factors that increase vulnerability to falls. • Describe assessment measures to determine gait and walking stability. • Describe the effects of restraints, and identify alternative safety interventions. • List several measures to reduce fall risks, and identify those at high risk. • Develop a plan of care for an older adult at risk for falls. Mobility is the capacity one has for movement within the personally available microcosm and macrocosm. This includes abilities such as moving oneself by turning over in bed, transferring from lying to sitting and sitting to standing, walking, using assistive devices, or transportation within the community environment. In infancy, moving about is the major mode of learning and interacting with the environment. In old age, one moves more slowly and purposefully, sometimes with more forethought and caution. Throughout life, movement remains a significant means of personal contact, sensation, exploration, pleasure, and control. Pride, maintaining dignity, self-care, independence, social contacts, and activity are all needs identified as important to elders, and all are facilitated by mobility. “Mobility is fundamental to active aging and is intimately linked to health status and quality of life” (Webber et al., 2010, p. 443). Impairment of mobility is an early predictor of physical disability and associated with poor outcomes such as falling, loss of independence, decreased quality of life, institutionalization, and death (Webber et al., 2010). Maintenance of mobility and functional ability for older adults is one of the most important aspects of gerontological nursing. Mobility and comparative degrees of agility are based on muscle strength, flexibility, postural stability, vibratory sensation, cognition, and perceptions of stability. Aging produces changes in muscles and joints, particularly of the back and legs. Strength and flexibility of muscles decrease and movements and range of motion (ROM) become more limited. Normal wear and tear reduce the smooth cartilage of joints. Movement is less fluid as one ages, and joints change as regeneration of tissue slows and muscle wasting occurs. Gait changes in late life include a narrower standing base, wider side-to-side swaying when walking, slowed responses, a greater reliance on proprioception, diminished arm swing, and increased care in gait. Steps are shorter, and there is a decrease in step height (lifting of the foot when taking a step). One third to one half of individuals 65 years of age or older report difficulties related to walking or climbing stairs (Webber et al., 2010). Sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass, strength and function), a condition prevalent in older people and a marker of frailty, contributes to mobility impairments and disability (Janssen, 2006). Limitations in mobility are approximately three times greater in older women and two times greater in older men with sarcopenia (Yeom et al., 2008). Findings from studies in the United Kingdom suggest that pre- and postnatal development of muscle fibers and muscle growth during puberty may have critical effects on musculoskeletal aging, development of sarcopenia, and risk of frailty (Kuh, 2007). Mobility impairments are caused by diseases and impairments across many organ systems. For some older people, osteoporosis, gait disorders, Parkinson’s disease, strokes, and arthritic conditions markedly affect movement and functional capacities. Mobility may be limited by paresthesias; hemiplegia; neuromotor disturbances; fractures; foot, knee, and hip problems; respiratory diseases, and illnesses that deplete one’s energy. All these conditions are likely to occur more frequently and have more devastating effects as one ages. Many older adults have some of these impairments, with women significantly outnumbering men in this respect (see Chapter 15). Regular physical activity throughout life is likely to enhance health and functional status as people age while also decreasing the number of chronic illnesses and functional limitations often assumed to be a part of growing older. The frail health and loss of function we associate with aging is in large part due to physical inactivity. A sedentary lifestyle, excess weight, and smoking are associated with mobility problems (Yeom et al., 2008). Few factors contribute as much to health in aging as being physically active. The old adage “Use it or lose it” certainly applies to our muscles and physical fitness (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2002. Assessment of functional abilities and screening should be included as part of the health assessment of all older adults. The purpose of screening is to (1) identify medical problems while allowing the individual to achieve the maximal benefit from physical activity; (2) identify functional limitations that will be addressed in the exercise program; and (3) minimize injury or other serious adverse effect. Exercise stress tests are no longer recommended by either the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force or the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association for the screening of low-risk, asymptomatic individuals before starting a physical activity program. The consensus is that there is minimal cardiovascular risk to engaging in physical activity and a much greater risk in maintaining a sedentary lifestyle (Resnick et al., 2006). The Exercise and Screening for You (EASY) tool (www.easyforyou.info) is a screening tool that can be used to determine a safe exercise program for older adults on the basis of underlying physical problems. The programs recommended have all been reviewed and endorsed by national organizations such as the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD) and can be printed and given to the person (Resnick, 2009). There are many resources available on the Internet that provide excellent information on physical activity in a useable format (see Evolve Resources). The Senior Fitness Test (SFT) is another instrument that has been used to assess physical fitness levels before and after an exercise intervention (Purath et al., 2009). The Get-Up-and Go Test (Mathias et al., 1986) (Figure 12-2) can also be used to assess mobility, gait, and gait speed. This tool is a practical assessment tool for older people that can be adapted to any setting. The client is asked to rise from a straight-backed chair, stand briefly, walk forward about 10 feet, turn, walk back to the chair, turn around and sit down. The test can be timed as well and gait speed has been found to be a predictor of mobility. On the basis of the results of initial screening, older adults may need further evaluation. Despite a large body of evidence about the benefits of physical activity to maintain and improve function, only about one third of men and 25% of women aged 65 to 74 years engage in leisure-time activity. With advancing age participation is even lower, with 16% of men and 11% of women 75 years and older engaged in leisure-time strengthening activities (lifting weights, calisthenics) (Purath et al., 2009; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010c). Older African-American women are the least physically active race-sex subgroup in the United States (Duru et al., 2010). Older people are also less likely to receive exercise counseling from their primary care providers than younger individuals. Research has noted that health care providers value the benefits of physical activity but have inadequate knowledge of specific recommendations (Tompkins et al., 2009; CDC, 2010c). The levels of physical activity among older adults have not improved over the past decade in the United States. Many older people mistakenly believe that they are too old to begin a fitness program. Physical activity is important for all older people, not just active healthy elders. Even a small amount of time (at least 30 minutes of moderate activity several days a week) can improve health. Physical activity is also associated with better cognitive functioning in old age. For women, physical activity at any time during the life course, especially as teenagers, is associated with a lower likelihood of cognitive impairment in later life (Middleton et al., 2010). Erickson and collegues reported that people 65 years of age and over who walked at least six miles a week had greater gray matter volume and halved their risk of developing memory problems (Erickson et al., 2010). Once weekly progressive strength training exercise programs have also been shown to improve cognitive abilities in women aged 65 to 75 years of age (Davis et al., 2010). Studies have found that increasing physical activity improves health outcomes in persons with chronic illnesses (regardless of severity) and in those with functional impairment (Sherrington et al., 2008; Yeom et al., 2009). The benefit of exercise (improvement in walking speed, strength, functional ability) of frail nursing home residents with diagnoses ranging from arthritis to lung disease and dementia has also been shown (Heyn et al., 2008). Physical activity can also improve emotional health and quality of life. Regardless of age or situation, the older person can find some activity suitable for his or her condition. It is important to keep older people moving any way possible for as long as possible. Following are examples of myriad ways in which older people keep fit: Recommendations for all adults are participation in 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity for five or more days of the week. People do not have to be active for 30 minutes at a time but can accumulate 30 minutes over 24 hours. As little as 10 minutes of exercise has health benefits and three 10-minute bouts of activity have the same fitness effects as one 30-minute bout. Health care practitioners should counsel all patients on how to incorporate exercise into their daily routines (CDC, 2010c). • Two hours and 30 minutes (150 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (e.g., brisk walking, swimming, bicycling) every week AND muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms) (CDC, 2010c). See www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/olderadults.html for video presentations of exercise as well as an explanation of guidelines and tips for physical activity. • Stretching (flexibility) and balance exercises (particularly for older people at risk of falls) are also recommended. Yoga and tai chi exercises have been shown to be of benefit to older people in terms of improving flexibility and balance as well as pain reduction and improved psychological well-being (Rogers et al., 2010). Tai chi can be adapted for level of function and mobility status (Wolf et al., 2006; Yeom et al., 2009) (Box 12-1). Home-based balance-training exercise programs are also available. One does not have to invest in expensive equipment or gym memberships or follow a structured exercise regimen to benefit from increased activity. The older person may be able to integrate activity into daily life rather than doing a specific exercise. Examples include walking to the store instead of driving, golfing, raking leaves, gardening, washing windows or floors, washing and waxing the car, and swimming. The Wii game system offers other possibilities for exercise at all levels and is increasingly being used in nursing homes and assisted living facilities to encourage physical activity and enjoyable entertainment. One study reported significant improvement in the ADL (activities of daily living) ability of frail community-dwelling older people following a program of twice-weekly water exercises. Benefits from the water exercise program were evident during the exercise period and for one year afterward (Sato et al., 2009). Water-based exercises are particularly beneficial for older people with arthritis or other mobility limitations. Nonambulatory older people can also engage in physical activity and may benefit most from an exercise program in terms of function and quality of life. “Muscle weakness and atrophy are probably the most functionally relevant and reversible aspects to exercise in nonambulatory older adults” (Resnick et al., 2006, p. 174). Suggested exercises might include upper extremity cycling, marching in place, stretching, range of motion, use of resistive bands, and chair yoga. At the Louis and Anne Green Memory and Wellness Center at Florida Atlantic University (Boca Raton, FL), 90-year-old Vera Paley leads groups of cognitively impaired elders as well as caregivers in chair yoga sessions. See Evolve resources for a DVD by Vera describing gentle chair yoga The benefits of physical activity extend to the more physically frail older adult, those with cognitive impairment, and those residing in assisted living facilities (ALFs) or skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) (Rolland et al., 2007; Heyn et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2009). Nurse researcher Barbara Resnick has written extensively on exercise and health promotion for older people and conducted numerous studies evaluating interventions to improve function and physical activity in older adults. The Res-Care intervention (Resnick et al., 2006), a self-efficacy–based approach to restore and/or maintain the residents’ physical function, can be used as a model for restorative care in ALFs and SNFs. The focus of restorative care is on “the restoration and/or maintenance of physical function and helping older adults to compensate for functional impairments so that the highest level of function is obtained and secondary complications of physical dependence are minimized” (Galik et al., 2009, p. 48). Restorative care programs should be integral activities in all facilities for older people. Following a recent study, the Res-Care intervention has been revised to be appropriate for individuals with moderate to severe cognitive impairment (Res-Care-CI) (Galik et al., 2009). This intervention holds promise to enhance therapeutic care of older adults with cognitive impairment and to focus interventions on quality of life rather than only on safety and behavior. Results of research suggest that older adults with cognitive impairment who participate in exercise rehabilitation programs have similar outcomes in strength and endurance as those who are not cognitively impaired (Heyn et al., 2008). However, those with cognitive impairment are often not included in physical activity programs or physical rehabilitation. Physical activity may also have a beneficial effect on mood in cognitively impaired older people. Nursing home residents who participated in a comprehensive 16-week exercise program with whole body movement (targeting balance, endurance, and upper and lower extremity strength), rather than walking alone, exhibited higher positive and lower negative affect and mood (Williams and Tappen, 2007a,b). Physical activity can be adapted in creative and enjoyable ways for people with cognitive impairment and may include activities such as ball toss, chair yoga, parachute toss, marching in place, shaking tambourines, dancing, Wii games, as well as ADL self-care activities and endurance and strength-training programs. Galik and colleagues (2009, p. 53) offer further suggestions for enhancing restorative nursing care programs for cognitively impaired nursing home residents, including “knowing what makes them tick, verbal encouragement, cueing, role modeling, humor and persistence.” Prescribing an exercise plan that includes the specific exercises the individual should do as well as the reasonable short- and long-term goals and safety tips is suggested. As suggested by the CDC, the program should include endurance, strength, balance, and flexibility (Table 12-1). Examples of strength-training exercises that can be done at home are presented in Figure 12-1. Varied activities that involve interaction with peers and fit the person’s lifestyle and culture will encourage participation (Yeom et al., 2009). The individual should be informed of resources in their community, and communities should be encouraged to provide accessible and affordable options for physical activity. Motivational interventions are important when encouraging older adults to begin and sustain a physical activity program. Collaborate with the individual on the goals they hope to achieve. Most older people are interested in how physical activity will improve the quality of their life and enhance their functional ability. The immediate benefits that can be expected should be emphasized—for example, improving walking ability or decreasing risk of falls. Specific types of exercises that are to be done daily as well as daily and long-term goals can be written down. Individuals can keep a journal or diary reflecting their experience and progress. TABLE 12-1 GUIDELINES FOR TEACHING ABOUT EXERCISE HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ROM, range of motion. Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: How much physical activity do older adults need? (2010c). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/olderadults.html. Accessed December 2010; Resnick B, Ory M, Rogers M, et al: Screening and prescribing exercise for older adults, Geriatrics and Aging 9:174, 2006. Follow up with the older individual so that they can share their progress. Support from experts such as nurse practitioners and family and peers is a significant factor in encouraging continued physical activity programs (Resnick et al., 2009, 2010). Group exercise programs with a lay trainer or nurse, and teaching a peer within the group to take on the leadership for long-term sustainability have been shown to be effective for older adults (Dorgo et al., 2009; Resnick, 2009). Duru and colleagues (2010) reported that a faith-based physical activity program (Sisters in Motion) led to an increase in walking and a decrease in systolic blood pressure among sedentary African-American women. Suggestions for exercise programs are presented in Box 12-2. Sharing stories of older people’s experience with physical fitness can be motivating. To hear the stories of older people (65 to 85 years) who maintain exercise regimens, see www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/getactive/olderadults.html. Similar to prescriptions for medication, a prescription for exercise should include potential exercise side effects, tips for prevention and management, and safety precautions (Box 12-3). Exercise side effects may include sensations associated with activity (shortness of breath) or things that might occur the day after exercise (muscle soreness) or more untoward things that require medical attention. Any exercise intervention should begin slowly and gradually progress with careful evaluation and monitoring of response. Proper instruction in technique and performance is important as well as the importance of warming up and cooling down. An extended cool-down period should be encouraged to diminish the risk of postexercise hypotension, syncopal episodes, or arrhythmias during recovery. Adequate hydration is important because total body water declines with age, and perspiration from exercise can increase the risk of dehydration. Proper footwear is also essential because of potential circulatory limitations, muscle sarcopenia, or degenerative changes in bones or joints. Falls are one of the most important geriatric syndromes and the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people older than 65 years (Gray-Micelli, 2008). One in three people aged 65 years and older falls each year (Rantz et al., 2008). Nursing home residents, who are more frail, fall frequently and repeatedly (Quigley et al., 2010). Falls among nursing home residents are estimated at 2.6 per year (Gray-Micelli, 2010). It is important to use a consistent definition of falls in practice and research because the word fall is interpreted in many different ways (Zecevic et al., 2006). A fall has been defined in the literature as unintentionally coming to rest on a lower area such as the ground or floor (Buchner et al., 1993). Often, the terms slips, trips, and falls are used interchangeably, and near falls, mishaps, or missteps, not usually reported, may be important in assessing fall risk. Exactly what constitutes a fall for reporting procedures in institutions is also problematic and can lead to inconsistencies in data (Zecevic et al., 2006). Therefore it is important to define a fall in words that seniors understand and to use an operational definition of falls in all research and fall-reporting data. Falls are a significant public health problem, and the rate of fall-related deaths among older persons has risen significantly over the past decade (Stevens et al., 2006) (Box 12-4). In the hospital, falls with resultant fractures, dislocations, and crushing injuries are considered one of the 10 hospital-acquired conditions (HCAs) that are not covered under Medicare. HCAs are conditions that (1) are high-cost or high-volume or both; (2) result in the assignment of a case to a DRG (diagnosis-related group) that has a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis; and (3) could reasonably have been prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines (www.cms.gov/HospitalAcqCond/06_Hospital-Acquired_Conditions.asp). Falls are considered a nursing-sensitive quality indicator. Patient falls have been reported to account for at least 40% of all hospital adverse occurrences (Ireland et al., 2010). All falls in the nursing home setting are considered sentinel events and must be reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Joint Commission (JC) has established national patient safety goals (NPSG) for fall reduction in all JC-approved institutions across the health care continuum (Capezuti et al., 2008). The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project has developed quality and safety measures for nursing and proposed targets for the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be developed in nursing prelicensure and graduate programs. Education on falls and fall risk reduction is an important consideration in the QSEN safety competency, which addresses the need to minimize risk of harm to patients and providers through both system effectiveness and individual performance (http://www.qsen.org/competencies.php). Falls are a symptom of a problem and are rarely benign in older people. The etiology of falls is multifactorial; falls may indicate neurological, sensory, cardiac, cognitive, medication, and musculoskeletal problems or impending illness. Episodes of acute illness or exacerbations of chronic illness are times of high fall risk. The presence of dementia increases risk for falls twofold, and individuals with dementia are also at increased risk of major injuries (fracture) related to falls (Oliver et al., 2007). In institutional settings, iatrogenic factors such as limited staffing, lack of toileting programs, and restraints and side rails also increase fall risk. A JC review of falls between 1995 and 2004 reported that the root causes of fatal falls included the following: (1) inadequate staff communication and training, (2) incomplete patient assessments and reassessments, (3) environmental issues, (4) incomplete care planning or delayed care provision, and (5) inadequate organizational culture of safety (Tzeng and Yin, 2008). Among older adults, falls are the leading cause of injury deaths and the most common cause of nonfatal injuries and hospital admissions for trauma (CDC, 2010a). Falls and their subsequent injuries result in physical and psychosocial consequences. Twenty percent to 30% of people who fall suffer moderate to severe injuries (bruises, hip fractures, TBI). Estimates are that up to two thirds of falls may be preventable (Lach, 2010). More than 95% of hip fractures among older adults are caused by falls. Hip fracture is the second leading cause of hospitalization for older people, occurring predominantly in older adults with underlying osteoporosis (Andersen et al., 2010). Hip fractures are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Negative outcomes include mortality; limitations in mobility; decline in bone mineral density, lean body mass, and strength; and quality of life issues such as persistent pain and depression. Only 50% to 60% of patients with hip fractures will recover their prefracture ambulation abilities in the first year postfracture. Older adults who fracture a hip have a five to eight times increased risk of mortality during the first three months after hip fracture. This excess mortality persists for 10 years after the fracture and is higher in men. Existing research also suggests that mortality and morbidity limitations are higher in nonwhite people as compared with white people. Most research on hip fractures has been conducted with older women, and further studies of both men and racially and culturally diverse older adults are necessary (Thompson et al., 2006; Andersen et al., 2010; CDC, 2010a; Haentjens et al., 2010). Older adults (75 years of age and older) have the highest rates of TBI-related hospitalization and death. TBI has been called the “silent epidemic” and older adults with TBI are an even more silent population within this epidemic. Falls are the leading cause of TBI for older adults (51%), and motor vehicle crashes are second (9%). In 2006, more than $2.8 billion was spent on treating TBI in individuals over the age of 65 years. Advancing age negatively affects the outcome after TBI, even with relatively minor head injuries (Timmons and Menaker, 2010). Yet, there is scant research on TBI and its management in older adults. Some authors question whether current protocols, based on work with younger adults, are appropriate for older people who may present differently with TBI (Thompson et al., 2006). A new CDC initiative, Help Seniors Live Better Longer: Prevent Brain Injury, provides educational resource materials on TBI for older adults, caregivers, and health care professionals in both Spanish and English (http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/seniors.html Factors that place the older adult at greater risk for TBI include the presence of comorbid conditions, use of aspirin and anticoagulants, and changes in the brain with age (Thompson et al., 2006). Brain changes with age, although clinically insignificant, do increase the risk of TBIs and especially subdural hematomas, which are much more common in older adults. There is a decreased adherence of the dura matter to the skull, increased fragility of bridging cerebral veins, an increase in the subarachnoid space, and atrophy of the brain, which creates more space within the cranial vault for blood to accumulate before symptoms appear (Karnath, 2004; Timmons and Menaker, 2010). Falls are the leading cause of TBI, but older people may experience TBI with seemingly more minor incidents (e.g., sharp turns or jarring movement of the head). Some patients may not even remember the incident. In cases of moderate to severe TBI, there will be cognitive and physical sequelae obvious at the time of injury or shortly afterward that will require emergency treatment. However, older adults who experience a minor incident with seemingly lesser trauma to the head often present with more insidious and delayed symptom onset. Because of changes in the aging brain, there is an increased risk for slowly expanding subdural hematomas. TBIs are often missed or misdiagnosed among older adults (CDC, 2010b). Health professionals should have a high suspicion of TBI in an older adult who falls and strikes the head or experiences even a more minor event, such as sudden twisting of the head. Further, symptoms of cognitive or physical decline occurring over a period of weeks or months should be investigated to rule out subdural hematomas. Manifestations of TBI are often misinterpreted as signs of dementia, which can lead to inaccurate prognoses and limit implementation of appropriate treatment (Flanagan et al., 2006). Table 12-2 presents signs and symptoms of TBI. TABLE 12-2 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY IN OLDER ADULTS From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Preventing Traumatic Brain Injury in Older Adults (2010). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/PreventingBrainInjury_Factsheet_508_080227.pdf. Accessed January 2011.

Mobility

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Mobility and Aging

Promoting Healthy Aging: Implications for Gerontological Nursing

Assessment

Interventions

Physical Fitness

Guidelines for Physical Activity

Special Considerations

![]() .

.

Aquatic exercise programs are beneficial for elders with mobility problems; they improve circulation, muscle strength, and endurance; and provide socialization and relaxation. (Copyright © Getty Images.)

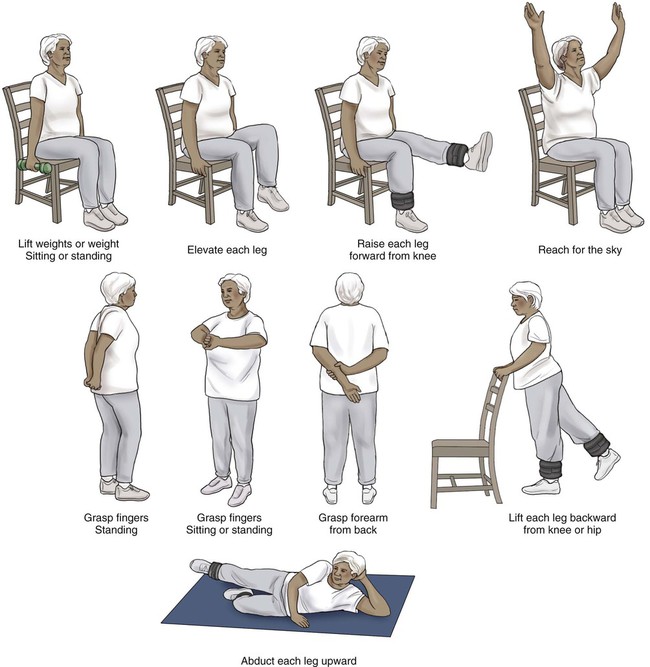

Exercise Prescription

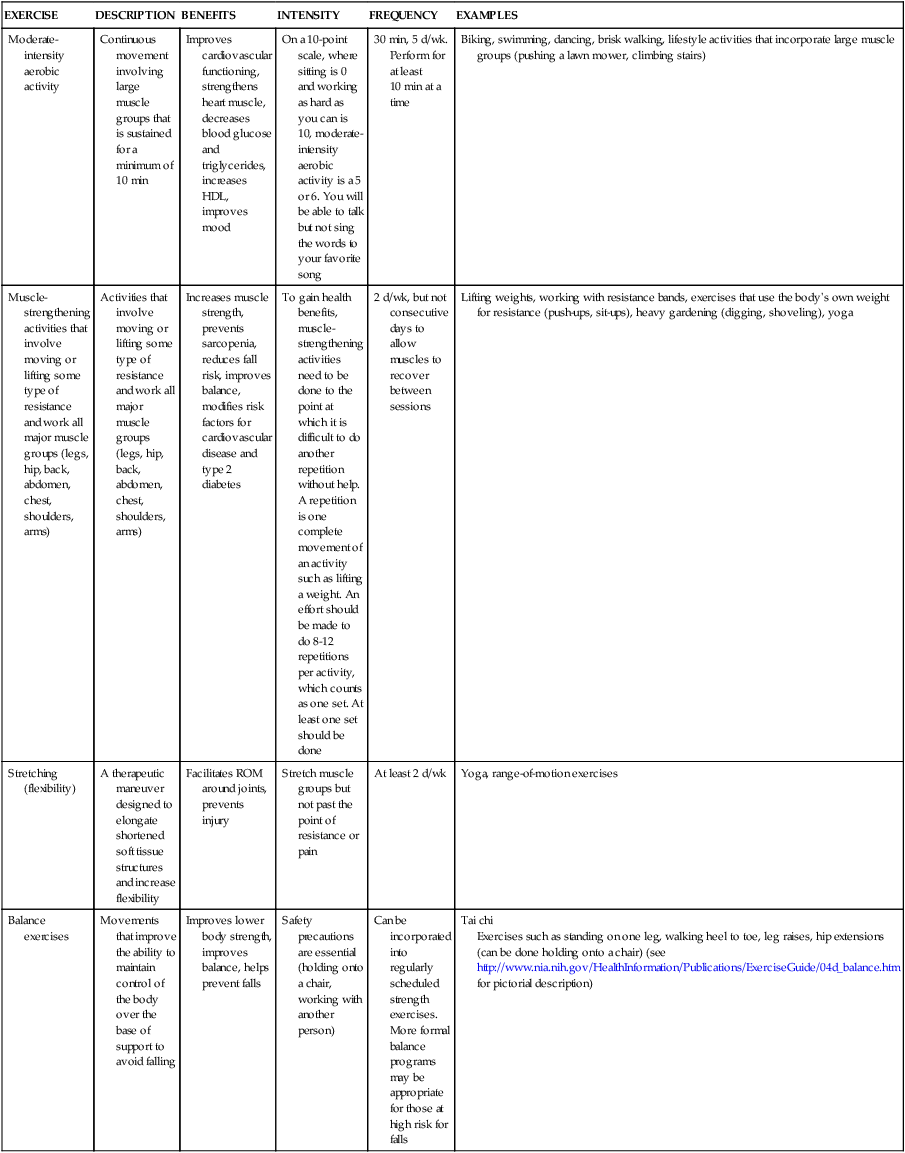

EXERCISE

DESCRIPTION

BENEFITS

INTENSITY

FREQUENCY

EXAMPLES

Moderate-intensity aerobic activity

Continuous movement involving large muscle groups that is sustained for a minimum of 10 min

Improves cardiovascular functioning, strengthens heart muscle, decreases blood glucose and triglycerides, increases HDL, improves mood

On a 10-point scale, where sitting is 0 and working as hard as you can is 10, moderate-intensity aerobic activity is a 5 or 6. You will be able to talk but not sing the words to your favorite song

30 min, 5 d/wk. Perform for at least 10 min at a time

Biking, swimming, dancing, brisk walking, lifestyle activities that incorporate large muscle groups (pushing a lawn mower, climbing stairs)

Muscle-strengthening activities that involve moving or lifting some type of resistance and work all major muscle groups (legs, hip, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, arms)

Activities that involve moving or lifting some type of resistance and work all major muscle groups (legs, hip, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, arms)

Increases muscle strength, prevents sarcopenia, reduces fall risk, improves balance, modifies risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes

To gain health benefits, muscle-strengthening activities need to be done to the point at which it is difficult to do another repetition without help. A repetition is one complete movement of an activity such as lifting a weight. An effort should be made to do 8-12 repetitions per activity, which counts as one set. At least one set should be done

2 d/wk, but not consecutive days to allow muscles to recover between sessions

Lifting weights, working with resistance bands, exercises that use the body’s own weight for resistance (push-ups, sit-ups), heavy gardening (digging, shoveling), yoga

Stretching (flexibility)

A therapeutic maneuver designed to elongate shortened soft tissue structures and increase flexibility

Facilitates ROM around joints, prevents injury

Stretch muscle groups but not past the point of resistance or pain

At least 2 d/wk

Yoga, range-of-motion exercises

Balance exercises

Movements that improve the ability to maintain control of the body over the base of support to avoid falling

Improves lower body strength, improves balance, helps prevent falls

Safety precautions are essential (holding onto a chair, working with another person)

Can be incorporated into regularly scheduled strength exercises. More formal balance programs may be appropriate for those at high risk for falls

Tai chi

Exercises such as standing on one leg, walking heel to toe, leg raises, hip extensions (can be done holding onto a chair) (see http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications/ExerciseGuide/04d_balance.htm for pictorial description)

Falls

Consequences of Falls

Hip Fractures

Traumatic Brain Injury

SYMPTOMS OF MILD TBI

SYMPTOMS OF MODERATE TO SEVERE TBI

Low-grade headache that won’t go away

Severe headache that gets worse or does not go away

Having more trouble than usual remembering things, paying attention or concentrating, organizing daily tasks, or making decisions and solving problems

Repeated vomiting or nausea

Slowness in thinking, speaking, acting, or reading

Seizures

Getting lost or easily confused

Inability to wake from sleep

Feeling tired all of the time, lack of energy or motivation

Dilation of one or both pupils

Change in sleep pattern (sleeping much longer than usual, having trouble sleeping)

Slurred speech

Loss of balance, feeling light-headed or dizzy

Weakness or numbness in the arms or legs

Increased sensitivity to sounds, lights, distractions

Loss of coordination

Blurred vision or eyes that tire easily

Loss of sense of taste or smell

Increased confusion, restlessness, or agitation

Ringing in the ears

Change in sexual drive

Mood changes (feeling sad, anxious, listless or becoming easily irritated or angry for little or no reason)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Mobility

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access