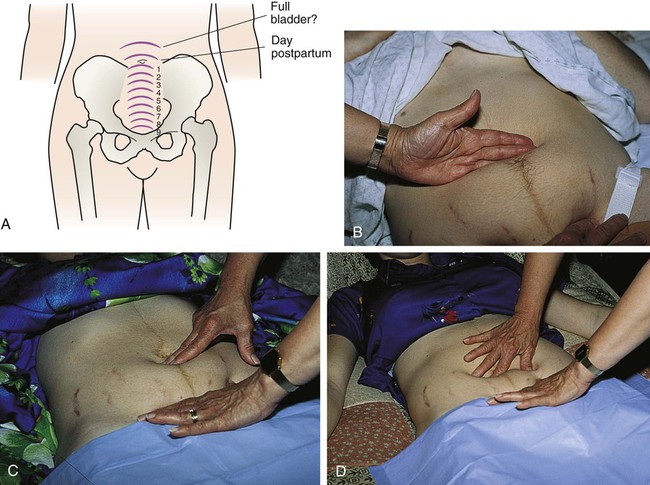

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the anatomic and physiologic changes that occur during the postpartum period. • Discuss characteristics of uterine involution and lochial flow and describe ways to measure them. • List expected values for vital signs and blood pressure, deviations from normal findings, and probable causes of the deviations. At the end of the third stage of labor, the uterus is in the midline, approximately 2 cm below the level of the umbilicus, with the fundus resting on the sacral promontory. At this time, the uterus weighs approximately 1000 g (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Within 12 hours, the fundus can rise to approximately 1 cm above the umbilicus (Fig. 18-1). By 24 hours after birth, the uterus is about the same size as it was at 20 weeks of gestation. Involution progresses rapidly during the next few days. The fundus descends 1 to 2 cm every 24 hours. By the sixth postpartum day, the fundus is normally located halfway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. The uterus should not be palpable abdominally after 2 weeks and should have returned to its nonpregnant location by 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2013). Subinvolution is the failure of the uterus to return to a nonpregnant state. The most common causes of subinvolution are retained placental fragments and infection (see Chapter 21). Postpartum hemostasis is achieved primarily by compression of intramyometrial blood vessels as the uterine muscle contracts rather than by platelet aggregation and clot formation. The hormone oxytocin, released from the pituitary gland, strengthens and coordinates these uterine contractions, which compress blood vessels and promote hemostasis. During the first 1 to 2 postpartum hours, uterine contractions may decrease in intensity and become uncoordinated. Because it is vital that the uterus remain firm and well contracted, exogenous oxytocin (Pitocin) is usually administered intravenously or intramuscularly immediately after expulsion of the placenta. The uterus is very sensitive to oxytocin during the first week or so after birth. Breastfeeding immediately after birth and in the early days postpartum increases the release of oxytocin, which decreases blood loss and reduces the risk for postpartum hemorrhage (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011). Immediately after the placenta and membranes are expelled, vascular constriction and thromboses reduce the placental site to an irregular nodular and elevated area. Upward growth of the endometrium causes sloughing of necrotic tissue and prevents the scar formation characteristic of normal wound healing. This unique healing process enables the endometrium to resume its usual cycle of changes and permit implantation and placentation in future pregnancies. Endometrial regeneration is completed by postpartum day 16, except at the placental site. Regeneration at the placental site usually is not complete until 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2013). Lochia rubra consists mainly of blood and decidual and trophoblastic debris. The flow pales, becoming pink or brown (lochia serosa) after 3 to 4 days. Lochia serosa consists of old blood, serum, leukocytes, and tissue debris. The median duration of lochia serosa discharge is 22 to 27 days (Katz, 2012). In most women, about 10 days after childbirth the drainage becomes yellow to white (lochia alba). Lochia alba consists of leukocytes, decidua, epithelial cells, mucus, serum, and bacteria. Lochia may continue for 2 to 6 weeks after the birth but may last longer and still be normal. Thus lochia persists up to 4 to 8 weeks after birth (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Persistence of lochia rubra early in the postpartum period suggests continued bleeding as a result of retained fragments of the placenta or membranes. Recurrence of bleeding 7 to 14 days after birth is from the healing placental site. About 10% to 15% of women will still be having normal lochia serosa discharge at their 6-week postpartum examination (Katz, 2012). However, in most women, the continued flow of lochia serosa or lochia alba by 3 to 4 weeks after birth can indicate endometritis, particularly if fever, pain, or abdominal tenderness is associated with the discharge. Lochia should smell like normal menstrual flow; an offensive odor usually indicates infection. Not all postpartal vaginal bleeding is lochia; vaginal bleeding after birth may be caused by unrepaired vaginal or cervical lacerations. Box 18-1 distinguishes between lochial and nonlochial bleeding. The cervix is soft immediately after birth. The ectocervix (portion of the cervix that protrudes into the vagina) appears bruised and has some small lacerations—optimal conditions for the development of infection. Over the next 12 to 18 hours, it shortens and becomes firmer. The cervical os, which dilated to 10 cm during labor, closes gradually. Within 2 to 3 days postpartum, it has shortened, become firm, and regained its form. The cervix up to the lower uterine segment remains edematous, thin, and fragile for several days after birth. By the second or third postpartum day, the cervix is dilated 2 to 3 cm, and by 1 week after birth, it is approximately 1 cm dilated (Blackburn, 2013). The external cervical os never regains its prepregnancy appearance; it no longer has a circular shape but, instead, appears as a jagged slit often described as a “fish mouth” (see Fig. 7-2). Lactation delays the production of cervical and other estrogen-influenced mucus and mucosal characteristics. Postpartum estrogen deprivation is responsible for the thinness of the vaginal mucosa and the absence of rugae. The greatly distended, smooth-walled vagina gradually decreases in size and regains tone, although it never completely returns to its prepregnancy state (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Rugae reappear within 3 weeks, but they are never as prominent as they are in the nulliparous woman. Most rugae are permanently flattened. The hymen remains as small tags of tissue that scar and form the myrtiform caruncles. The mucosa remains atrophic in the lactating woman, at least until menstruation resumes. Thickening of the vaginal mucosa occurs with the return of ovarian function. Estrogen deficiency is responsible for a decreased amount of vaginal lubrication. Localized dryness and coital discomfort (dyspareunia) can persist until ovarian function returns and menstruation resumes. The use of a water-soluble lubricant during sexual intercourse is usually recommended. Most episiotomies and laceration repairs are visible only if the woman is lying on her side with her upper buttock raised or if she is placed in the lithotomy position. A good light source is essential for visualization of some repairs. Healing of an episiotomy or laceration is the same way as that of any surgical incision. Signs of infection (pain, redness, warmth, swelling, or discharge) or loss of approximation (separation of the edges of the incision) may occur. Initial healing occurs within 2 to 3 weeks, but 4 to 6 months can be required for the repair to heal completely (Blackburn, 2013). If forceps were used for the birth, the woman may have experienced vaginal or cervical lacerations; hematomas of the pelvic soft tissues can also occur with forceps-assisted birth (see Chapter 17). Hemorrhoids (anal varicosities) are commonly seen (see Fig. 7-10). Internal hemorrhoids can evert while the woman is pushing during birth. Women often experience associated symptoms such as itching, discomfort, and bright red bleeding upon defecation. Hemorrhoids usually decrease in size within 6 weeks of childbirth. The supporting structure of the uterus and vagina can be injured during childbirth and contributes to later gynecologic problems. Supportive tissues of the pelvic floor that are torn or stretched during childbirth can require up to 6 months to regain tone. Kegel exercises, which help strengthen perineal muscles and encourage healing, are recommended after childbirth (see Guidelines box, p. 57). Later in life, women can experience pelvic relaxation—the lengthening and weakening of the fascial supports of pelvic structures. These structures include the uterus, upper posterior vaginal wall, urethra, bladder, and rectum. Although relaxation can occur in any woman, it is commonly a direct but delayed complication of childbirth.

Maternal Physiologic Changes

Reproductive System and Associated Structures

Uterus

Involution Process

Contractions

Placental Site

Lochia

Cervix

Vagina and Perineum

Pelvic Muscular Support

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access