Melissa LaCour By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. Explain the purpose of the master patient index. 2. Maintain the accuracy of a master patient index. 3. Determine whether a patient has a previous health record at the facility. 4. Compare and contrast numbering systems for identification of patient records. 5. Compare and contrast filing systems for patient records. 6. File health records appropriately according to the file system used by the facility. 7. Maintain accuracy of filing methods. 8. Identify the alternative storage system best suited for a particular health care facility. 9. Explain a chart locator system. 10. Determine the appropriate file space for a given set of circumstances. 11. Compare various computer storage architectures. 12. Identify ways to ensure the physical security of health information. 13. Determine the retention schedule for specific health care records. chart locator system cloud computing computer output to laser disk (COLD) enterprise master patient index (EMPI) family unit numbering system file folder index master patient index (MPI) medical record number (MR#) microfiche microfilm middle-digit filing system optical disk outguide patient account number record retention schedule redundant arrays of independent disks (RAIDs) retention scanner serial numbering system serial-unit numbering system storage area network (SAN) straight numerical filing terminal-digit filing system unit numbering system Earlier chapters discussed the recording of patient data for communication. The accuracy, validity, and completeness of health data are all necessary in order for the data to be useful. Yet storage, too, is an important aspect of managing health records. HIM departments must have the appropriate shelf space and furniture to accommodate paper records as well as the computer hardware and software to facilitate workflow, efficient access, and secure storage for vast amounts of electronic files. Previous patient data may communicate to a physician important information necessary for treatment. A patient’s health care may depend on the physician’s review of the patient’s previous health records. Therefore it is important to make sure the patient’s health data are recorded, organized, and analyzed in the health record and stored in a way that allows the information to be retrieved when the patient returns to the facility for follow-up care. What happens if the physician cannot locate the patient’s health record from the last visit? What if comparison of the notes from the previous visit with the present information reflects a significant weight loss for the patient, or a current test result must be compared with a previous result? This information may be important in the care and treatment of the patient. For example, it could change the patient’s dosage of a particular medication or indicate a new diagnosis. HIM professionals systematically collect and organize a patient’s health information to create a timely, accurate, and complete record. Health information is vital not only to the patient but also to the health care provider and the community. HIM departments routinely provide health information on request to authorized users. The patient’s health record, whether paper or electronic, must be retained for the continuity of patient care, and for reimbursement, accreditation, potential litigation, research, and education purposes. This information must be stored in a secure, organized environment and accessible to those who need it. This chapter explores the issues of health record storage for electronic and paper records, including computer hardware and storage capacity, file identification, filing systems, filing furniture, scanning, and security of the file environment. It also discusses alternative storage methods, including offsite storage and microfilm. The organized storage of the health record begins with appropriate identification of each patient’s record. Whether the facility maintains paper health records or works in a hybrid or electronic environment, the master patient index (MPI) is the primary tool for identifying a file for each patient the facility has seen. The master patient index (MPI) is used to maintain the information and location of each patient admitted to the facility. Originally, before computers, an MPI was a manual system maintained on index cards organized in a file cabinet in alphabetical and numerical order; today it is a computerized system. The data contained in the MPI are the data collected during the patient registration process. At registration, an identification number and a medical record number (MR#) are assigned. This unique number is used to individually identify each patient within that health care facility. The process of recording the registration data into the MPI and generating the MR # initiates the patient’s health record. Each health care facility has an MPI. The MPI is a list of all patients who have received health care services at the facility. When looking for the health record of a particular patient, staff in the patient registration department must first find out whether the patient has previously received services at the health care facility and then determine the patient’s medical record number. They use the MPI to obtain this information. The MPI correlates the patient with the facility’s medical record number to identify the patient’s health record. Box 9-1 lists the recommended and optional contents of an MPI. The information contained in the MPI is a combination of the demographic, financial, and clinical data. Each patient is entered only once in the MPI. All visits for a particular patient are listed in the MPI under the patient’s name. HIM professionals are very careful to prevent duplication of patients within the MPI, because it may cause confusion and delay in retrieval of patient files. In previously used manual MPI systems, as patients were registered in the facility, the HIM department was notified of the admission. The notification might have been a copy of the face sheet, a computer printout of the admission, or the admit log. The HIM department created an index card in the MPI for each patient who was registered in the health care facility. If the patient had been treated at the facility on a previous occasion, the patient’s MPI card was retrieved from the card file, reviewed to make sure the patient’s information was correct, and the new admission information added (date of admission, type of service, account number for that visit, attending physician, discharge date). The MPI had to be updated each time the patient was admitted to the health care facility so that all health care services were listed on the card. Figure 9-1 illustrates a manual MPI card. Today, the MPI is computerized even if the HIM department maintains paper health records. A modern, computerized MPI is more robust than a manual system. It captures more patient information and can be accessed from areas outside the HIM department, such as the emergency department and patient registration. A computerized MPI system uses software to capture and store patient identification and admission information. The computerized MPI software is typically one feature of a larger electronic health record (EHR) system or is interfaced with other information systems in the health care facility. Information entered into a computerized MPI creates a history for each patient. At registration, the admitting clerk searches the MPI history files to determine whether the patient has been treated at the facility on a previous occasion. If the patient is new, a new history is created by entering the information listed in Box 9-1. If the patient has been treated at the facility on a previous occasion, the admitting clerk identifies the patient’s history and reviews it to ensure the accuracy of all of the information. Any changes to the patient’s address, phone number, or health insurance should be documented in the MPI. Figure 9-2 shows a computerized MPI screen, the results of a search for patient Mary Davidson. Notice that there are two results. The example shown is an MPI for a multihospital system in which all of the facilities share an MPI. This system is commonly called an enterprise master patient index (EMPI). This particular MPI indicates that that Mary Davidson has been a patient in two different health care facilities within the multihospital system. The EMPI improves access to records and allows for easy retrieval of the patient’s health information when authorized. Though each facility within the multi-hospital system maintains its own patient health records, the facilities share an EMPI in order to manage patient encounters. The computerized MPI can also help resolve the use of an alias (AKA, or also known as) and “merges” for a particular patient. The AKA feature links any other names for this patient (e.g., maiden name). The merge feature can identify whether any duplicate numbers have been assigned to a patient; this knowledge can be helpful if a chart was incorrectly filed under a duplicate patient number. There are advantages and disadvantages to a computerized MPI. The computerized MPI provides the opportunity to store more patient identification information for each admission—for example, patient financial class, marital status, social security number, and AKA functions, which link the patient to another name resulting from divorce or marriage or to a pseudonym. More information is stored in a smaller space combined with greater search capabilities to access possible matches for a name using phonetics, date of birth, Social Security number, or age. Information systems also allow the MPI to be linked to other departments. The disadvantage of a computerized MPI is that it is not available during computer down time or power outages. Therefore, a printout of key fields for emergency lookup or locally installed backup are “manual” solutions that provide access to the data when the system is not available. Regardless of format or type, it is necessary to maintain an accurate MPI. The most common errors include duplication of patient entries and misspelling of patient names. When they are identified, an HIM professional must carefully follow procedures to correct each error and to properly identify the patient in the MPI and with the correlating record. If a patient has more than one entry in the MPI, the HIM professional must be sure to correct all associated records to reflect the accurate number and patient. If the patient’s name is incorrect, this information must also be corrected wherever it appears to ensure accurate retrieval of patient information. Failure to maintain an accurate MPI can impact patient care because information may be unavailable or incomplete and not accessible when needed at the point of care. Inaccuracies can also impact reimbursement and compliance if the MPI is used to correlate patient visits with appropriate billing or claims processing. The MPI must be retained by the health care facility permanently. This index is extremely important in the everyday operations of the health care facility and the HIM department. In a numerical filing system (discussed later in this chapter), the medical record number (MR#) is necessary to retrieve the patient’s health record. The MPI is the easiest way to access the patient’s medical record number. When a facility implements a computerized MPI, it must decide what to do with the manual system. Because the information in an MPI is never destroyed, the facility must devise a way to convert the information from the manual file into the computerized system. One method to retain the data on the manual MPI cards is to enter the MPI information in the new computerized system, allowing computer access to all MPI information. When this process is performed the facility must ensure the accuracy of the converted MPI data if it plans to dispose of the original MPI system. In other situations the MPI cards are scanned and maintained in an imaging system. This is an efficient way to maintain the original MPI system for future research if MPI data are questioned. HIM professionals should monitor the accuracy of the manual MPI conversion. If the information on even one patient or encounter is omitted or entered incorrectly, the MPI is not accurate. The omission or error may cause great difficulty for anyone accessing patient records. Maintenance of the original MPI information secures the validity of the data in the computerized MPI and provides a reference if a discrepancy arises in a patient’s file that originated before the conversion. The ability to reference the original MPI cards allows the correction of any discrepancies caused by an error or omission. In this type of conversion, the facility should consider storing the manual MPI in the original format or microfilming the original MPI cards for future reference. The minor inconvenience caused by storing the manual system can prevent serious problems with record discrepancies in the future. Prior to the EHR, paper health record documents were stored in physical file folders. For easy identification and filing, the file folder containing the patient’s health information was labeled with alphanumerical characters. In a small health care facility or a physician’s office, the file folder might be identified alphabetically with the patient’s name. In a large health care facility, the MR# was used to identify the patient’s health record file. MR#s vary in length: Some are only six digits, others are eight or nine digits, and some may even be longer. Currently, the number of digits or type of number used by a facility is not mandated. However, accreditation agencies such as The Joint Commission (TJC) require facilities to use a system that ensures timely access to patient information when requested for patient care or other authorized use. Additionally, the facility chooses the system that best suits its purpose for identification and storage of patient files. Five types of health record identification are discussed here: alphabetical filing, unit numbering, serial numbering, serial-unit numbering, and family unit numbering. While you are learning these identification methods, keep in mind that a numbering system is not the same as a filing method. In a small physician’s office, clinic, home health care facility, or nursing home, the patient health record file folders are often labeled using the patients’ names. Thus, the “numbering” and “alphabetical” filing systems are the same. The health record file for the patient John Adams is identified thus: Adams, John. File folders are arranged on the shelf in alphabetical order, beginning with the patient’s last name (Figure 9-3). For those records stored on a shelf, the patient’s name is color coded on the side tab, often using the first three letters of the patient’s last name. The records are still filed alphabetically, but the labeling is different. In the alphabetical system in which records are filed in a cabinet, the folder is labeled with the patient’s name, preferably on the top tab (Figure 9-4, A and B). Alphabetical filing works well in health care environments where the number of patient visits or records is relatively low. The file folders are easy to label, and pulling a patient’s file can be accomplished if the patient’s name is known. Health care professionals in facilities using this system must take special care to protect the privacy of patient records because the patient health information is easily identified. Alphabetical filing does not require an additional system, such as the MPI, to correlate patient names and numbers to identify a particular file folder. Problems can arise when two patients have the same name. Common names require careful attention to be certain that the correct patient record is found. Think about the names Michael, Joe, and Ann. How many other ways may these names be identified? Mike, Michael, Jo, Joe, Joseph, José, Josef, Ann, Anne, Annie, and Annette are common versions of Michael, Joe, and Ann, respectively. When duplicate names occur in an alphabetical filing system, procedures must be specified to further organize the records by the patient’s middle name, by titles (Jr., Sr., III), or by the patient’s date of birth (DOB). Common rules for alphabetical filing are as follows: • Abbreviations, nicknames, and shortened names are filed as written (e.g., Wm, Bud, Rob). • When identical names occur, consider the DOB for filing order and proceed chronologically. Patients’ files must be clearly labeled. It is important to print clearly when labeling the patient’s file folder. This is not an occasion for fancy script or calligraphy. Illegible or fancy handwriting may cause a file folder to be misfiled. Table 9-1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of alphabetical filing. TABLE 9-1 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF ALPHABETICAL FILING Space is a common problem in the alphabetical filing system. The shelves or cabinets holding the files of patients’ names beginning with common letters become full very quickly, so HIM departments must allow adequate file space for these letters of the alphabet. Filing in a section that is full of records is difficult and requires shifting of the records for further filing. Alphabetical filing systems can become inefficient in a facility that serves a large population with a high volume of patient records. Another consideration with this system is the spelling of patient names. In an alphabetical file system, a folder labeled incorrectly because of misspelling will not be filed correctly. When the HIM employee attempts to locate the patient’s folder, efforts will involve searching for a misspelled, misfiled record. When unsure of the spelling of the patient’s name, the person taking the information from the patient should ask for identification to clarify the spelling. In a unit numbering system, a patient receives the same medical record number for each admission to the facility. Therefore the numerical identification of each individual patient is always patient specific. For example, if a person is born in a facility that uses unit numbering, at birth (which is considered an admission) the patient is assigned a number (e.g., MR# 001234). Any subsequent admissions of this patient to the facility would use the same MR#. In a unit numbering identification system, the patient’s medical record number remains the same, within the facility, throughout the lifetime of the patient. Medical record numbers are not shared and are not reused after a patient dies. Consider the following scenario: Molly Brabant is born at Diamonte Hospital on January 1, 2001. At birth, Molly is assigned MR# 001234. Her birth record is filed in a folder identified with MR# 001234. At age 7, Molly returns to the same facility to have a tonsillectomy. Molly’s new records are stored in the same folder identified as MR# 001234. Any subsequent admissions (e.g., for a hip replacement later in life) are filed under the same number (Figure 9-5). In a serial numbering system, a new medical record number is assigned each time a patient has an encounter at the facility. In this type of system, the patient’s file folders containing the health record for each encounter are not filed in the same folder. Therefore the records are not typically located together on the file shelf. In the previous scenario but with a serial numbering system, Molly Brabant is assigned MR# 001234 at birth. However, when she returns at age 7 for a tonsillectomy, a new number, MR# 112233, is assigned (Figure 9-6). In this system, Molly’s records are not stored in the same folder, and they are not located near one another on the file shelf. Molly now has two separate folders containing her health record, and she receives a third MR# and a new folder when she visits the facility for a hip replacement in later years. The number assigned during each one of Molly’s encounters is recorded in the MPI under her name. A serial-unit numbering system is a combination of the previous two numbering systems. In this system, the patient receives a new medical record number each time he or she comes into a facility. The difference is that each time the patient receives health care, the old records are brought forward and filed with the most recent visit, under a new medical record number. This system requires a cross-reference system from the old MR# to the new number so that records can be located. For cross-referencing, the MPI must be updated so each encounter reflects the corresponding medical record number, and a file guide is placed in the old file location alerting HIM employees to look for the current MR# to locate the patient’s health record. In the previous scenario using a serial-unit numbering system, Molly is assigned MR# 001234 at birth, and on return 7 years later for a tonsillectomy, she is assigned a new number, MR# 112233. When Molly returns for the tonsillectomy, the birth record (MR# 001234) is retrieved from its place in the files and combined with the file folder MR# 112233. A cross-reference should be set up by insertion of an outguide (see Figure 9-16) in place of the old MR# 001234 to indicate that the record is now filed at MR# 112233 (Figure 9-7). Molly’s records are transferred and cross-referenced a third time when Molly has a hip replacement later in life. In rare cases in health care settings where it is common for an entire family to visit a physician or clinic, and often to have the same insurance carrier, an entire family’s records may be identified using one medical record number. Each family members file is then identified by the one medical record number to the entire family (father/husband, mother/wife, and children). This system is called a family unit numbering system. A modifier is placed at the end of the family unit number unique to each member of the family. The modifier is a number attached to the MR# using a hyphen. Each member of the family can be identified by a modifier associated with his or her position in the family: head of household, 01; spouse, 02; first born, 03; second born, 04; and so on. With this system, all of the family members’ records may be contained in one file folder. In our example, Molly’s family unit number is MR# 123456. At birth, Molly, being the first-born child, is assigned MR# 123456-03. Molly’s mother has MR# 123456-02. The last two numbers after the hyphen indicate to which family member the record belongs. Table 9-2 provides an example of family unit numbering. TABLE 9-2 This system is also beneficial in a small clinic or physician’s office setting where clinical and financial records are combined for claims processing. There are potential problems with this numbering system, however. Families change, couples divorce, and grown children marry and adopt other names. When members of the family divorce, die, marry, or remarry, the medical records for those patients must be renumbered. This process can be quite tedious. Even in a family unit numbering system, the facility is responsible for maintaining the confidentiality of each patient’s health information. Safeguards must be taken to ensure that husbands and wives are allowed access to each other’s information only with appropriate authorization (see Chapter 12). Likewise, procedures should exist to safeguard the confidentiality of a child’s information after he or she reaches the legal age of majority. Each facility should examine the positive and negative aspects of each numbering identification system to choose the system that allows the most efficient delivery of health care for its patients. The system should have a positive impact on both employee and facility productivity. Table 9-3 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each numbering system. TABLE 9-3 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF NUMBERING SYSTEMS In some health care facilities the patient account number is used to identify the patient health record. The patient account number is unique because it is specific to the encounter or health care service the patient receives. Patient account numbers are not typically duplicated and therefore can easily be used as an additional method of identifying a patient health record. For instance, in some facilities the number generated for the health care service may easily indicate whether a patient was treated in the emergency room, ambulatory surgery center, or outpatient clinic. In a scanned imaging system this information can be used as one of the index values helping HIM professionals search for a patient record or document. In the EHR the patient account number is a data field that can be used to search for patient records. A legacy system is a method or computerized system formerly used by the health care facility (or any organization). As changes occur in health care, this term is used by HIM professionals to refer to the “old” way or system used. For many organizations, the manual/paper filing methods discussed in this chapter are legacy systems. It is important to recognize the value of these systems and to understand them so that the information they contain can be retrieved and used as needed for patient care. Filing is the process of organizing the health record folders on a shelf, in a file cabinet, or in a computer system. There are some common methods for organizing paper-based health records in a file area: alphabetical, middle-digit, straight numerical, and terminal-digit. Alphabetical filing was described previously in the discussion on identification of files. In an electronic system, patient health information is indexed; this issue is discussed at the end of this section.

Managing Health Records

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Master Patient Index

Development

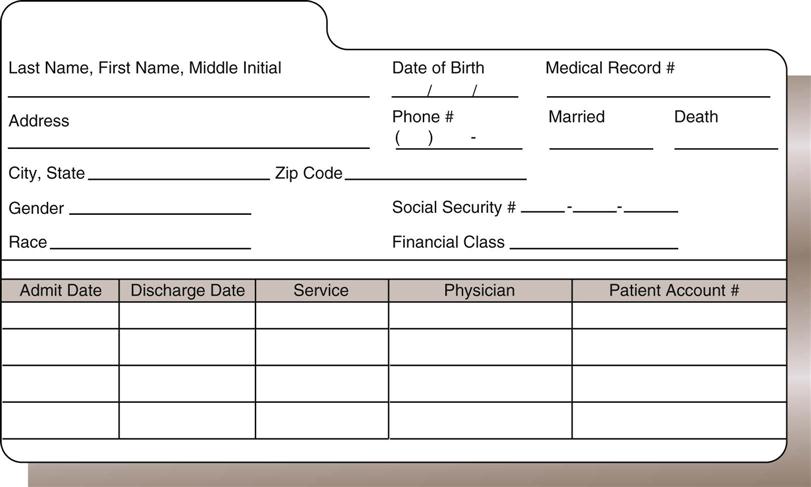

Manual Master Patient Index

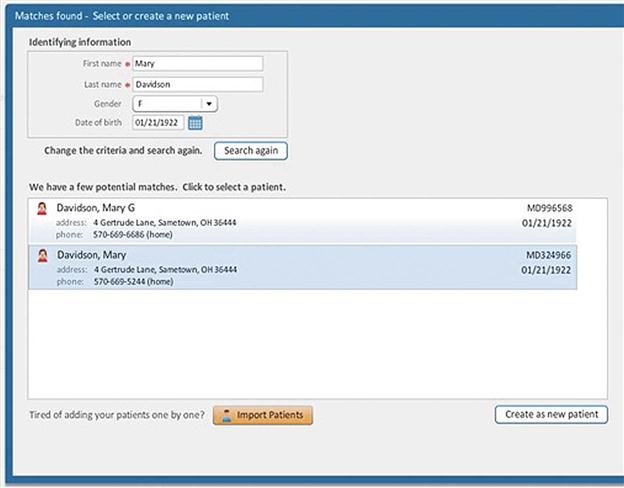

Computerized Master Patient Index

Maintenance

Retention

Identification of Physical Files

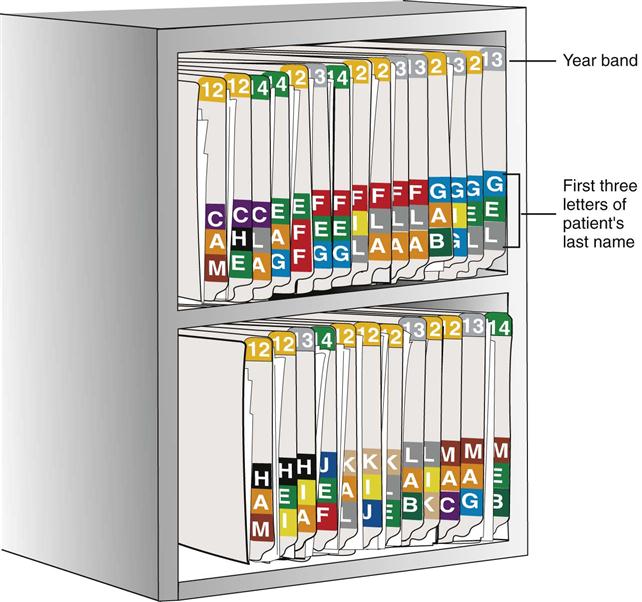

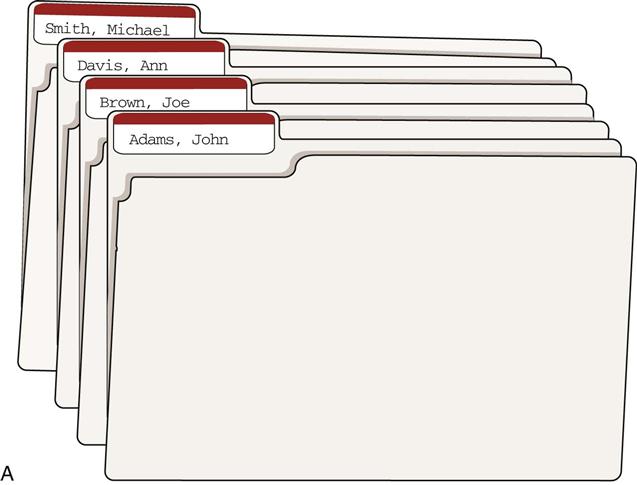

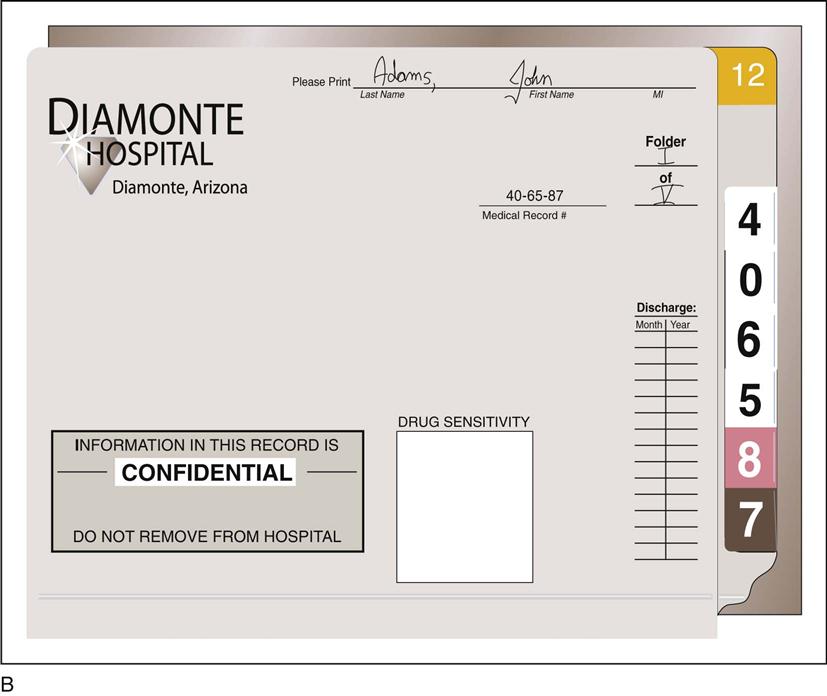

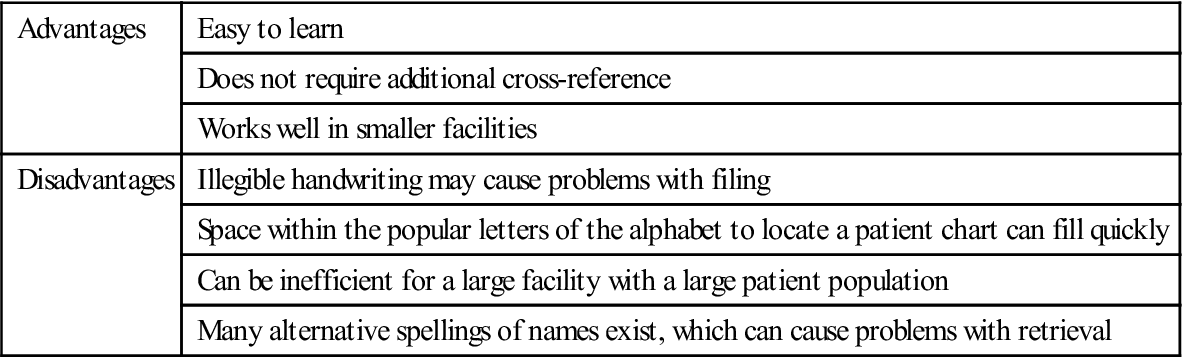

Alphabetical Filing

Advantages

Easy to learn

Does not require additional cross-reference

Works well in smaller facilities

Disadvantages

Illegible handwriting may cause problems with filing

Space within the popular letters of the alphabet to locate a patient chart can fill quickly

Can be inefficient for a large facility with a large patient population

Many alternative spellings of names exist, which can cause problems with retrieval

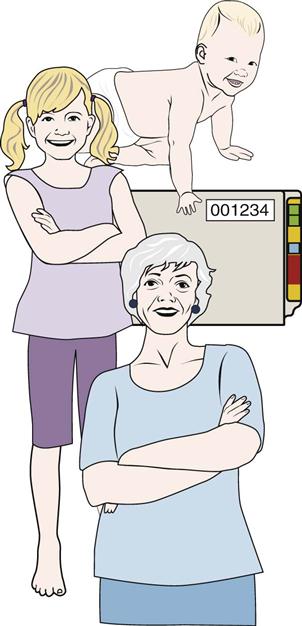

Unit Numbering

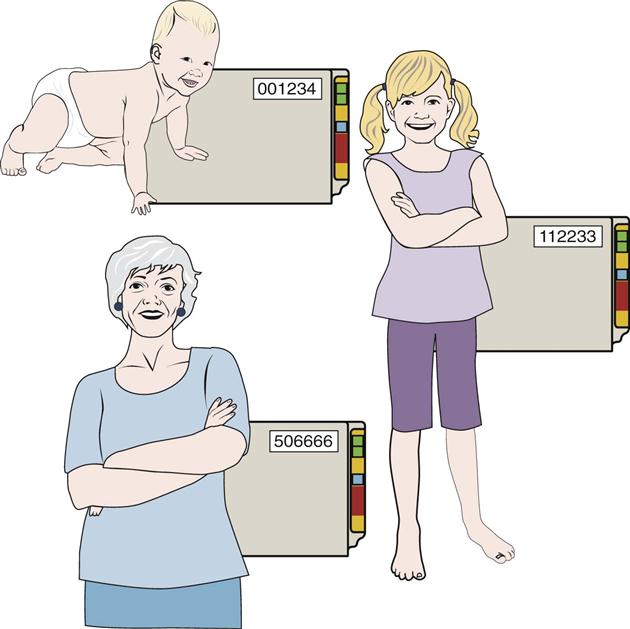

Serial Numbering

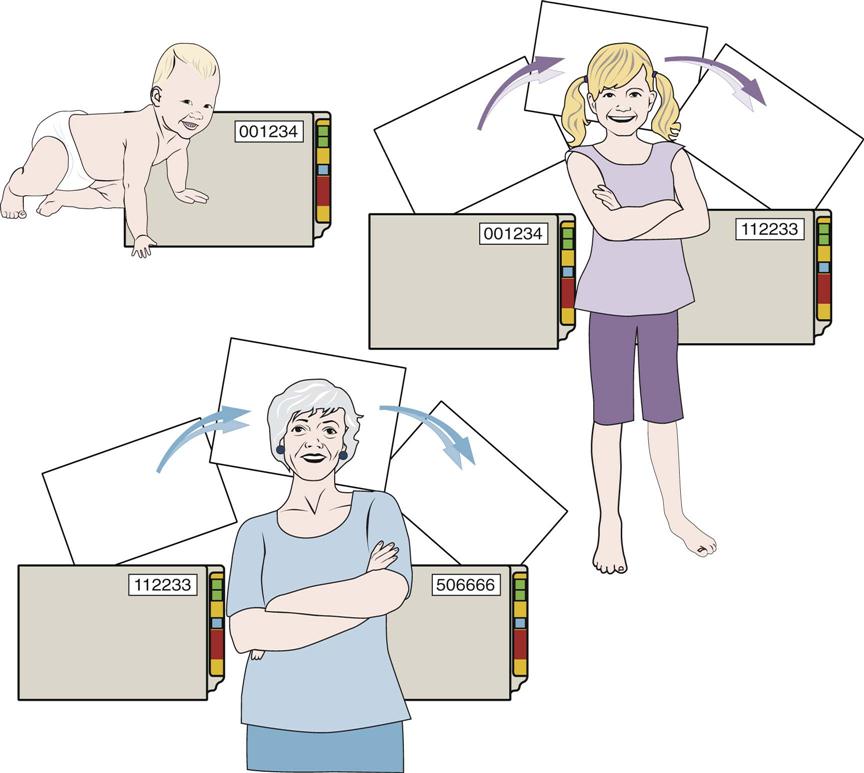

Serial-Unit Numbering

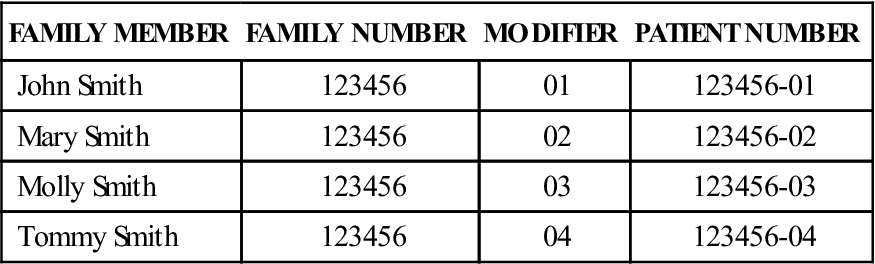

Family Unit Numbering

FAMILY MEMBER

FAMILY NUMBER

MODIFIER

PATIENT NUMBER

John Smith

123456

01

123456-01

Mary Smith

123456

02

123456-02

Molly Smith

123456

03

123456-03

Tommy Smith

123456

04

123456-04

SYSTEM

ADVANTAGE

DISADVANTAGE(S)

Unit

All patient records can be located under one number.

Filing of all encounters in one folder can cause problems with incomplete records.

Serial

Each admission is filed in a single folder.

Retrieving all the records for one patient involves going to multiple places in the files.

Serial-unit

Each admission has a unique number, but they are all filed with the most recent.

This method is time consuming.

Family unit

Records are files together for clinical and financial processing of claims.

Confidentiality can be compromised; divorce, remarriage, and other factors can create complications.

Patient Accounting

Legacy Systems

Filing Methods

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Managing Health Records

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access