A second common source of team conflict relates to disagreements over goals. Such conflict may be due to the absence of a clear vision or clear goals, with individual team members substituting their own differing perceptions. Or, again, individual team members may have real differences in the goals they prefer for the team. This source of conflict is particularly apparent on interprofessional teams, because each profession brings different values and expectations for patient care to the team, as described in Chapter 3. An example is the preference of one team member to involve more family members in a team discussion, which may not be perceived as practical (or desirable) by other team members.

Conflict escalates when critical resources are scarce. For example, suppose 6 clinical professionals on a patient care team share the services of one clerical staff team member. If financial circumstances change such that the team only can afford a half-time clerical staff member, the 6 team members are more likely to engage in conflict over who gets the available time from the half-time clerical staff member.

Differences in perceived status or rank are potent sources of conflict on interprofessional teams. If members treat each other differently based on status, resentment on the part of the lower status member is likely to result. Lower status members are less likely to participate fully in team activities, or they may even work against team goals. Higher status members are more likely to devalue the contribution of the lower status members. A net result is increased levels of conflict or potential conflict in the team.

Conflict escalates when tasks are more interdependent, based on the simple fact that interdependent members must rely on other members, and things do not always go as planned. A team member who needs the input of another team member before making a recommendation for treatment, for instance, may resent the delay caused by a colleague who is late providing the input. In particular, interdependence is high during handoffs—transfer of responsibility and information from one member to another—making handoffs a common source of conflict in interprofessional team care.

Finally, a host of additional causes of conflict can be classified as personal. Team members may dislike other members for their personal characteristics, such as personality, religion, political views, appearance, or behavioral idiosyncrasies. While these sources of conflict are not based on features of the team or on characteristics of individuals specific to their team roles, conflicts arising for personal reasons can affect team performance.

Several of these causal factors were interacting to create the potential for conflict in the allergy practice described in the introductory vignette. Role ambiguity around who enters the test results was evident. All of the staff members were not on board with the proposition that electronic records would improve the quality of patient care, a goal clarification issue. Differences in perceived status likely entered into staff members’ reluctance to confront Dr. Andersen with their issues. Task interdependence meant that if one staff member had a delay, others often were affected. The personal preference of Dr. Andersen to “tough it out” through adversity likely was not in line with the feelings of some or all of the staff.

Given that virtually all interprofessional teams have built-in status differences, scarce resources, multiple professional backgrounds, interdependent tasks, and members with personal differences, it is no wonder that the potential for conflict is high in interprofessional teams. How should such conflicts be handled? When should conflict be stimulated rather than reduced? A next step is to differentiate among types and stages of conflict.

TYPES AND STAGES OF TEAM CONFLICT

Diego Jimenez, MBA, loosened his tie. This meeting of the emergency department (ED) process flow project team was going to be a long one. Mr. Jimenez had administrative responsibility for the ED and headed the team, which was charged with reducing patient waiting time in the ED. Two ED physicians, 3 RNs, and 4 other clinical technicians or clerical staff members were on the team. Trouble had been simmering between one of the staff members (a front desk receptionist) and one of the nurses for several meetings, but at this meeting it spilled out in the open, with the front desk receptionist accusing the nurse of being lazy. In addition, several team members seemed to be using the process flow project to make the case for new equipment, such as faster personal computers, rather than thinking more broadly about other causes of delay in serving patients. Finally, the team was having trouble deciding how to proceed next with data collection: short interviews with a sample of ED personnel, or written surveys of all personnel.

Types of Team Conflict

Types of Team Conflict

It is useful to identify types of team conflict because type of conflict is related to decisions about how to manage the conflict. Three types of team conflict are commonly distinguished: relationship, process, and task (Thompson, 2011, pp. 183-185). While conflict often is of multiple types or morphs over time from one type into a different type, the 3 categories help provide a context for considering (1) the value of the conflict for team learning, and (2) how and when to surface or resolve the conflict. Table 11–2 summarizes the types of team conflict and examples of each type.

Team conflict can occur among individual team members or among combinations of team members. At its simplest level, team conflict occurs between 2 individual team members, as it did between the receptionist and the nurse in the vignette. When conflict surfaces, though, other team members likely will take positions. Opinions on issues often coalesce around a small number of positions, so conflict often involves one coalition of members versus another, or conflict among multiple coalitions.

Relationship conflict is conflict over personal or social issues not related to the team task. It often is referred to by teamwork scholars as “emotional” or “affective” conflict. For example, team members may disagree about health policy or other political issues that are largely irrelevant to the team’s work. Or, team members may have different opinions about professional appearance and dress. (In both cases, such conflict actually could be relevant to the team’s work if it affects patient care or other team performance goals.) In the preceding vignette, the accusation that another person is lazy is tangential to the team task and therefore is primarily a symptom of relationship conflict. On the other hand, the accuser might consider the issue to be relevant to the team task, because laziness may contribute to delays in serving patients. Often, relationship conflicts do have some degree of relevance to team processes or team tasks.

Relationship conflict frequently is detrimental to team performance: as relationship conflict increases, team effectiveness decreases. In general, relationship conflict is best handled outside of the purview of the team. Experienced conflict handlers take their issues “outside of the room” and address them privately so that they do not interfere with team tasks. We say more about this in the following section.

Task conflict is conflict over the content of the work that is being done by the team. It is the most critical of the types of conflict for teams to monitor and process. One teamwork commentator (Wheelan, 2013, p. 27) argues that disagreement over goals and values largely is inevitable, and that conflict is necessary in order to create a climate where members feel free to disagree with each other. It is easier for members to develop trust in each other if they believe that they can disagree and will not be abandoned or hurt because they have different perspectives. An example of task conflict in the preceding vignette is the discussion of old equipment as a factor in patient delay. Some team members feel that new equipment would improve patient flow; others likely think it would be of marginal value. Another example of task conflict, on a patient care team, is disagreement about the appropriate therapy for a patient. Conflict over tasks ideally is depersonalized, and therefore also is referred to as cognitive conflict. Task conflict typically consists of arguments about the merits of ideas, plans, and therapies. Task conflict frequently is useful for teams because it leads to new insights and allows for efficient progress—everyone gets “on the same page” about the content of the team’s work.

Process conflict is conflict over the way that the work of the team is being done, with the issue of role ambiguity—who does what—being a potent source of process conflict. An example is conflict over who should communicate a team decision to a patient, or when. Like task conflict, process conflict frequently can be useful in creating efficient movement forward in accomplishing a team’s task, and it should be encouraged and surfaced up to a point. In the vignette, process conflict has emerged over the best way to collect data for the ED process flow team to review.

Together, task conflict and process conflict can be called substantive conflict, in contrast to relationship conflict, because they are conflict over the substance of the team’s work—what to do and how to do it. Recalling the first vignette about electronic health record implementation, the potential conflict in Dr. Andersen’s allergy practice involved both task and process issues, in that there was conflict over the value of the task of implementing the electronic record (task conflict), as well as numerous issues about how best to accomplish the task (process conflict). The relationship of substantive conflict to team effectiveness can be visualized in the shape of an inverted U: effectiveness increases with conflict levels, up to a point. After that point, effectiveness decreases. (See Figure 11–1.) Teams can be overwhelmed if every process or task issue invites disagreement, and if team members learn to argue over every issue on the team agenda. A certain level of constructive conflict, though, should be encouraged. It clarifies roles and goals, creates cohesion because members feel that their feelings are heard, and surfaces new ideas and viewpoints. When followed by actions to address problems, open disagreement promotes change and innovation (Reay et al, 2013). Hopefully Mr. Jimenez, in the preceding vignette, will be able to use the disagreements about task content and process to move the team forward.

Stages of Team Conflict

Stages of Team Conflict

All types of conflict generally proceed through stages, from anticipation of the conflict on the part of one or more parties, to awareness of the conflict short of confirmation, to discussion which confirms that the conflict exists (or not), to open dispute. The stages can proceed almost instantaneously in the case of acutely erupting conflicts, or conflicts can simmer in the anticipation or awareness stages for months or years. Conflict can also stop at any of the stages.

In the case of the ED process flow team, Mr. Jimenez was aware of some bad feelings between front desk personnel and some of the nurses in the ED. Discussion and open dispute had not occurred in a formal setting, though, so it was difficult to judge its seriousness. Had he anticipated the conflict emerging in the team setting, Mr. Jimenez could have intervened to prevent it from being surfaced then, or he could have been more prepared to deal with the conflict when it did surface.

Inter-Team Conflict

Inter-Team Conflict

In addition to intra-team conflict, the types and stages of conflict generalize to conflict among different teams. For example, in the same organization, multiple teams may be responsible for care to different populations of patients, and the teams may come into conflict over resources provided by the organization to each team. Or, teams that perform different stages of interdependent work for the same population of patients may fight over the appropriate scope and responsibility of each team. For example, teams in the primary care department of a large medical group may argue with teams in the orthopedics department about who should order diagnostic imaging services. The methods of managing team conflict described in the next section also can be applied to conflict among teams, although surfacing and resolving those conflicts may be more difficult because regular communication channels among different teams may be lacking. The organizational context for teams affects the way that conflict among teams is managed. The organizational context for teamwork is covered in Chapter 18.

Process and task conflict require team attention, as does relationship conflict that affects team performance. Methods to address conflict are covered next.

MANAGING TEAM CONFLICT

Jerry Nichols, NP, a gerontological nurse practitioner, headed to the weekly meeting of the home care team with a grimace on his face. In addition to Mr. Nichols, the team included an occupational therapist, a social worker, a physician assistant, and a primary care physician. The team leader was the primary care physician, Amy Bristol, MD. Other professionals, such as nutritionists, pharmacists, speech therapists, and home health aides, were invited to team meetings as needed, and patients and family members were also considered as team members.

The team does valuable work in these meetings, Mr. Nichols thought, but it meets too often. Weekly meetings are not necessary. Meeting every 2 weeks should be sufficient, as team members could e-mail or telephone others if there really were urgent business between meetings.

Although Mr. Nichols suspected that other team members also shared his concern, he did not know how to bring it up with the team’s leader, Dr. Bristol. When Dr. Bristol joined the team a year ago, she had stressed how important it was to meet weekly “come hell or high water,” in order to “stay ahead of the wave” and deliver the highest quality care.

Five Methods of Conflict Management

Five Methods of Conflict Management

A quite common (overly common, many experts argue) method of managing conflict is avoidance. This is the first of 5 commonly discussed methods of managing conflict (Thomas, 1977). Avoidance is a frequent choice by busy healthcare professionals who are not comfortable with surfacing conflict (Skjørshammer, 2001). Drinka and Clark (2000, pp. 150-151) provide a long list of excuses (22 in number) that healthcare teams use to rationalize avoidance of conflict. Among common rationalizations are: the patient comes first (allowing a member to avoid addressing another member’s concerns); procrastination; overoptimism (Everything is fine; I don’t know what you are talking about); beepermania (the reader can guess how that one works); and too busy—no time. Team members may avoid conflict in the name of efficiency, but constructive conflict is actually a time saver (Lencioni, 2002, p. 203). Teams that avoid constructive conflict may revisit issues again and again without resolution and may be plagued with ongoing tension. Teams that avoid conflict may have boring meetings, ignore controversial topics, fail to tap into perspectives of team members, and waste time with interpersonal attacks. In contrast, teams that engage in constructive conflict have lively meetings, exploit the ideas of all team members, solve real problems more quickly, minimize the use of politics, and put critical topics on the table for discussion (Lencioni, 2002, p. 204).

Why is avoidance such a common response to conflict? Many people find conflict to be threatening, based on past negative experience or the belief that harmony requires keeping silent. Some cultures, particularly many Asian cultures, emphasize harmony and the avoidance of open conflict as a social norm. The emphasis on collaboration in interprofessional teams (imparted by books—including this book—and competency frameworks for interprofessional practice such as the US and Canadian frameworks covered in Chapter 7) reinforces the reluctance to surface conflict, as well. In fact, however, avoiding conflict can cause negative feelings to build and can deprive teams of relevant and important information and new ideas.

In the case of the home care team described earlier, if Mr. Nichols chooses to keep silent about his discomfort with the weekly meeting schedule, he is using avoidance to manage the situation. Maybe the weekly meeting issue is not important enough for Mr. Nichols to raise. Maybe he will not let the issue influence his performance on the team, and all will be well. But most likely, Mr. Nichols’ frustration will influence his participation and performance, and avoidance is not a good solution.

Accommodation is an option as well. Accommodation requires that one party to the conflict give in to another party. An accommodative solution to the conflict in the vignette first would require that the conflict be surfaced. Mr. Nichols could talk to Dr. Bristol individually, for example, and the team leader then could decide whether to put the issue on the agenda for team discussion. Prior to responding to Mr. Nichols, Dr. Bristol might individually raise the issue with other key team members to assess their feelings. If Dr. Bristol then tells Mr. Nichols, “I think we’re working well with the weekly schedule, so let’s keep it that way,” and Mr. Nichols agrees to drop the issue, he is being accommodating to the team leader. If Dr. Bristol concludes, “Jerry, you’ve got a good point, and I’ll change the schedule as you suggest,” the leader is engaging in accommodation. (In neither of those cases is the conflict formally processed by the team, though, so the accommodations are by the individuals involved rather than the team.)

A third option, collaboration, is the “gold standard” method of dealing with conflict. Collaboration has a specific meaning in the conflict management field (Quinn et al, 2011, p. 94; Thomas, 1977, 1988), narrower than the broad notion of collaboration as a teamwork competency. As a conflict management method, collaboration proceeds through (1) an airing of the multiple sides of an issue, (2) agreement on criteria for resolving the conflict, and (3) negotiation of a solution acceptable to all parties to the conflict. Collaboration is similar to “win-win” negotiation, popularized by Fisher and Ury in their classic book, Getting to Yes (1981). A key component of the win-win negotiation process is separating people from problems—depersonalizing the conflicts. The goal of win-win negotiation is to create new value for all parties, rather than having one party dominate the other parties, or leaving all parties dissatisfied.

Following is an example of collaborative resolution of the conflict about weekly meetings, described earlier. Team leader Dr. Bristol agrees to put the issue on the next meeting agenda. She begins the team discussion by noting that “our key interest here is quality of patient care, rather than convenience for ourselves, right—does everyone agree with that?” Following affirmation of that criterion for making a decision, several members of the team air opinions about the weekly meeting schedule, ranging from “we don’t meet often enough” to “once a week is about right” to Mr. Nichols’ opinion that once a week is too often. Mr. Nichols realizes that he is alone in his opinion. The team agrees by consensus (see Chapter 9) to continue the meetings every week, but agrees that if there is no pressing business, the meeting will be canceled. Mr. Nichols agrees to support the collaborative solution. The outcome is not much different than the outcome produced by avoidance or accommodation by Mr. Nichols, as no major change is made in the meeting schedule. However, Mr. Nichols does appreciate the possibility of having some meetings cancelled. Most importantly, Mr. Nichols now better understands and accepts the tenor of the team on this issue, and the team has acknowledged and listened to his frustration. Mr. Nichols remains committed to making the team work.

A fourth method of managing conflict is compromise, a close relative of collaboration. To achieve compromise, multiple parties (1) air their sides of an issue, (2) agree on criteria for resolution, and (3) negotiate a solution acceptable to all parties. The steps are identical to collaboration. Compromise receives second billing to collaboration, however, because the solution is less desirable to each party. No party gets what they originally want—by definition, each side gives up something from its original position, and no new, better solution is substituted. In contrast, with collaboration, a new and better solution is discovered. Admittedly, the distinction between collaboration and compromise often is more intellectual than practical, as new win-win solutions (resulting from collaboration) may still be viewed as less than optimal by each party in the same way that compromise solutions are viewed as less than optimal by each party.

Here is an example of a compromise solution to the weekly meeting issue: hold weekly meetings for 1 month, biweekly meetings the next month, and so on, producing 6 meetings instead of 8 meetings in every 2-month period. This might emerge in a team discussion if enough support for Mr. Nichols’ position is expressed in the discussion. No side gets its original preference, so the sides split the difference. Neither side is fully satisfied.

When team members confront an issue but do not accommodate, collaborate, or compromise, competition is a fifth and final option for managing conflict. The members compete with each other, with one member a victor and the others losers. Teams that make decisions by competition typically employ political tactics. Political tactics use power, which typically derives from one’s position (with the leader commonly holding more power), profession (with physicians commonly holding more power), or expertise (with more experienced or more highly educated professionals holding more power). An unspoken rule might be, for example, that the team leader makes decisions on most issues—she or he has position power. In a competitive solution to Mr. Nichols’ quandary about weekly meetings, team leader Dr. Bristol would simply rebuff Mr. Nichols’ request to have a team discussion of the meeting schedule, essentially winning that competition. To escalate the competition politically, though, Mr. Nichols could lobby other members to get the issue on the agenda. Dr. Bristol likely would relent if faced with enough pressure and would agree to a team discussion. A debate likely would ensue, and a team vote might seal the decision. The winners would celebrate (silently, hopefully) and the losers would be unhappy.

If powerful leaders or coalitions choose to exercise their power in competitive conflict resolution, the competition can demoralize and marginalize the other team members. Competition often is referred to as a forcing response to conflict, as resolution is forced on the other parties. The cultural norm of collaboration is strong in most settings and situations in healthcare delivery, however, which tempers the use of competition to resolve conflicts.

Balancing Inquiry and Advocacy

Balancing Inquiry and Advocacy

The 5 methods of conflict management can be arrayed by degree of inquiry and degree of advocacy involved. Competition requires the highest degree of advocacy for one’s position, with avoidance and accommodation requiring little or no advocacy, and collaboration and compromise at the moderate level. Inquiry (soliciting and listening to the position of others) is highest for the compromise and collaborate methods (as well as the accommodate method) and is low for competition and avoidance. For thoughtful exchange, a balance of inquiry and advocacy is advised (Argyris and Schön, 1996, p. 117; Bolman and Deal, 2008, pp. 172-173). Labeled Model II thinking, combining advocacy with inquiry requires that participants openly express what they think and feel, while they actively seek understanding of other’s thoughts and feelings. People suspend their assumptions, but they communicate their assumptions freely in open dialogue. Systems theorist Peter Senge notes that an emphasis on advocacy can be counterproductive, particularly when team members are not familiar with each other’s work and experience. When team members are not in touch with the potential contributions of others, they need to inquire even more. Senge (1990, pp. 200-202) suggests that the competency of dialogue requires that people should follow 4 guidelines:

1. When advocating, clarify your own reasoning and encourage others to ask questions that explore how you arrived at a particular position. Encourage others to provide different views.

2. When inquiring, ask others to explain their assumptions and how they arrived at their conclusions. If you are making assumptions of your own about others’ views, state your assumptions clearly.

3. If you arrive at an impasse, ask what additional information or logic you and the other parties might need to change your views. Ask if there is some way you might gather additional information.

4. If members are hesitant to express their ideas, encourage them to identify barriers. Design ways of overcoming those barriers.

Collaboration and compromise require high levels of both inquiry and advocacy, as proponents of positions are open and forthcoming about their own positions, and are able to see the other side, which enables them to feel good about compromise or collaboration. Team members who can listen with understanding rather than evaluation and who can accept the feelings of the involved individuals are able to contribute most to collaboration and compromise.

Situational Use of Conflict Management Methods

Situational Use of Conflict Management Methods

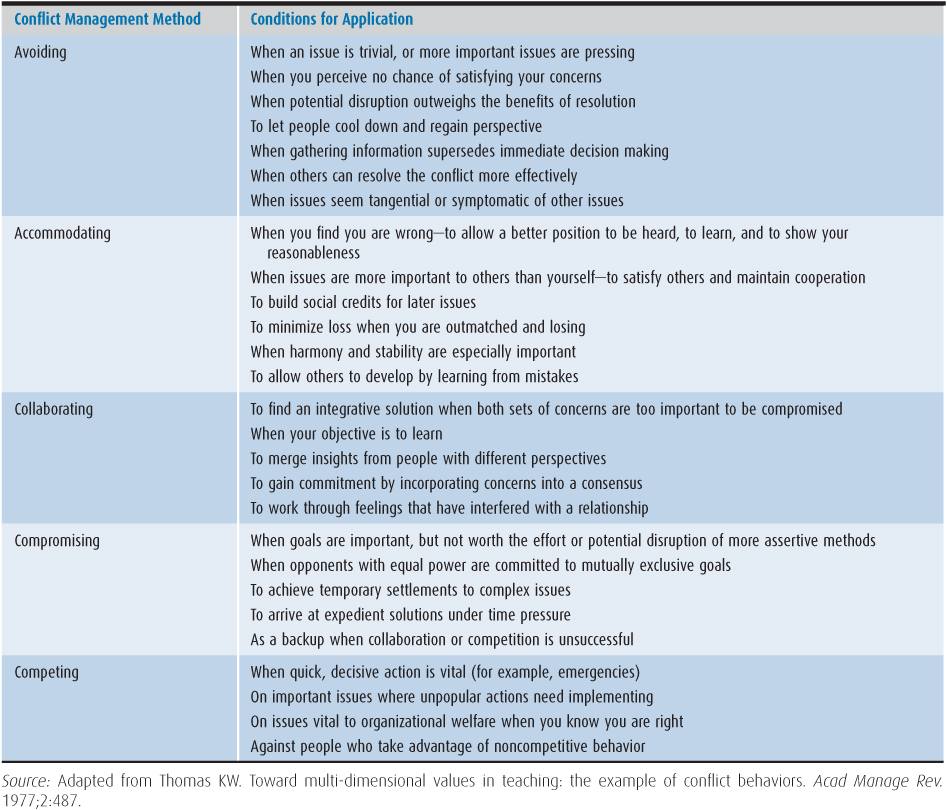

While collaboration may be a gold standard method of conflict management, its use is not ideal in all situations. Other options are gold standards too, given certain conditions. This is an important point, given the emphasis on collaboration in interprofessional work. Thomas (1977) notes that collaboration has been emphasized as an ideal in the study of organizations and management, and to be uncollaborative is not viewed positively in most settings. Yet behavioral choices surrounding conflict situations are much more complex than the one dimension of collaboration. Thomas notes that the alternatives of competition, compromise, avoidance, and accommodation also are positively viewed in the appropriate circumstances. Competition is associated with energy in the pursuit of excellence. Compromise is a cornerstone of practicality. Avoidance is associated with tranquility, peace, and diplomacy. Accommodation reflects values of humility, kindness, and generosity.

Table 11–3 lists some of the conditions that are suggestive of each of the 5 conflict management methods. Avoidance, while overused, is appropriate for issues that are trivial or require more information or a “cooling down” period before the issue is addressed. Accommodating others may make sense to build trust or to keep the peace when harmony is critical. Competing is useful for quick decisions, requiring a powerful leader or coalition to impose their will. Quick decisions imposed by leaders are critical in healthcare teams facing emergency conditions, particularly if the team members do not know and trust each other, as is the case for many template teams (see Chapter 2). Competing also is useful for distasteful decisions where the options are all unpalatable. Finally, for issues of important principle or moral issues, members may be unwilling to compromise or collaborate, requiring that competitive decision making ensue. For example, competition is often the ultimate way to get decisions made in the legislative arena.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree