family assumes a greater decision-making role and often becomes the major focus of teaching. The expected outcomes of the teaching plan include control of fear and anxiety and maximization of patient and family coping strategies. Specific attention review of the precautions that will be taken by the surgical team to minimize the risks of surgery (prophylactic antibiotics prior to incision, neuronavigation and neuromonitoring to reduce the risk of neurological injury, intraoperative imaging to confirm surgical site, etc.) may help to reduce anxiety and strengthen the relationship between the patient/family/friends and the nurse/physician team. Common related patient problems include knowledge deficit, anxiety, fear, and family dysfunction.

TABLE 14-1 GENERAL PREOPERATIVE TEACHING PLAN FOR NEUROSURGICAL PROCEDURES | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 14-2 PERIOPERATIVE CHECKLIST | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

validate the patient’s identification with patient, patient’s significant other(s), identification bracelet, and medical records. Once the patient receives anesthesia, the surgical team depends on the identification bracelet for verifying blood, medication, specimen, etc.

review the medical records to verify operative procedure, informed consent notes, medical history, and physical examination.

verify the presence of consent form with surgeon’s and patient’s signature. If the patient’s cognitive level is impaired or the patient is a minor, then the next of kin, conservator, or guardian signs the consent.

validate the operative site and ensures site marking, if appropriate.

assess NPO status and appropriate studies, reporting any deviations.

verify allergies.

determine the availability of blood and blood products. In some cases, packed red blood cells (RBCs) or other blood products may be sent to the OR suite “standing by” for any emergency needs.

assess the physical status including vital signs, respiratory status, cardiovascular, renal, skin, sensory and motor, and nutritional status.

assess presence of communicable disease.

note any physical abnormalities, injuries and previous surgery. Identify prosthesis, implants, and external fixator.

screen for substance abuse.

identify any personal belongings of the patient, including dentures, jewelry, clothing, glasses, hearing aids, etc. If possible, ask the patient’s family to keep them.

assess the psychosocial status of patient/significant others, including perception of surgery, expectation of surgical care and postoperative care, cultural and religious practices, and cognitive level.

check preoperative orders and administer premedication per prescriptions.

Check environment status: room temperature, humidity, and electrical.

Ensure cleanliness and safety of general environment.

Check proper functioning of basic equipment: electrocautery (Bovie), suction, OR lights, computer, appropriate OR bed, and other basic furniture.

Ensure the readiness of specific equipment requested by the surgeon: microscope, laser, ultrasonic aspirator, navigation system, intraoperative CT scan and ultra-sonogram, C-arm or O-arm, neuromonitoring, EEG monitoring, and deep brain recorder.

Gather all positioning devices: Mayfield skull clamp and pins or horseshoe, head holder for portable CT or MRI, bolsters (if prone), bean bag with extra pillows and multi-task armboard (if lateral).

Ensure the availability of implants and specific instrumentation.

Obtain and dispense medications/solutions for the sterile back table.

Do the initial count (all sponges, Raney clips, needles, cottonoids, needles and all small items) with the scrub nurse/technician prior to patient entering the OR suite.

Clearly post case information (patient’s names and IDs, procedure, counts, medications, allergies, availability of blood products, and all personnel) on a white board that is visible to all members in the room.

Ensure safe transfer of patient to OR bed from either a Gurney or regular patient’s bed. Ensure adequate help, if patient is overweight or difficult positioning is performed.

Assist and support anesthesiologist during induction, intubations, and other pre- and postinduction procedures (such as peripheral lines, central line, and arterial line).

Protect the eyes from corneal abrasions; this is often accomplished with application of a bland eye ointment and taping the eyelids closed; sterile eye pads may be applied.

If not already present, insert an indwelling urinary catheter as indicated.

Apply lower extremity SCDs to prevent pooling of blood in the lower extremities (can lead to DVT).

Cover the patient with blanket of an air pump warmer. If hypothermic therapy is required, the temperature of the air pump can be adjusted to room temperature or cooler.

Initiate the surgical time out accordingly to institutional policy. Each member (perioperative nurse, scrub nurse/technician, surgeon, anesthesiologist) of the team takes turn, and verbally announces and confirms the patient’s identification, procedure, and the surgical site. The nurse announces the time out is done when it is completed.

Perform skin preparation with prep solution per surgeon preference. Prevent prep solution, especially alcoholic solution, from entering eyes and ears, which causes irritation.

Preferably, keep hair in place. However, for craniotomy, if hair is removed, it should be removed by clipping only. Shaving is considered the least acceptable way of hair removal because studies show that it increases the infection rate.2, 3

Monitor the patient’s general condition including vital signs, blood loss, and irrigation used.

Deliver specimens/cultures to the appropriate laboratory with patient identifier and name of the specimen. Send frozen section/cultures immediately.

Communicate with patient’s family regularly and provide appropriate updates.

Perform two final counts of all countable items with the scrub nurse/technician. Inform the surgeon if there is anything missing, and start searching for the missing item immediately.

Keep an accurate OR record, including time, personnel, procedure, used supplies and instrument, implants and explants, medications, patient care plan, specimens collected, counts, timeout procedure, etc.

Give report to Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU) nurse 30 minutes before the incision is closed. Assist the surgeon to apply dressing.

Assist and support anesthesiologist to wake the patient up from anesthesia and extubate if indicated.

Transfer the patient to the PACU safely on a gurney/ICU bed.

observe pressure points before or after the surgery, and protect those areas with extra padding, such as foam or gel pads, intraoperatively.

place and support all extremities in natural position, if possible, to avoid peripheral nerve injury.

check the proper function of the Mayfield clamp before applying on the patient. Improper application of the skull clamp and pressure of the pins may cause slipping which results in laceration and bleeding at the pin sites.

Prone position may increase bleeding in spine procedure due to high abdominal venous pressure. Check PEEP pressure because prone can restrict respiratory function, especially overweight patient. If Mayfield skull clamp is used, make sure nose and chin are not pressed on the head holder and mattress. If prone pillow is used, make sure both eyes are free from pressure. It has been frequently reported that blindness can be the result of prolonged high intraocular pressure during surgery.4, 5 To protect the brachial plexus, soft padding should be placed under axilla and both upper extremities should be flexed with an angle less than 90 degrees, if they are placed on armboard.

Supine position has less complication. Observe all pressure points and protect them with foam or gel pads.

Align the head and neck with the axis of the body when patient is in lateral position. Arms are supported with armboard/pillows and adequate padding. Place an axillary roll, made of foam pads and Webril, under the axilla for protection of the axillary nerve. Lower extremities should be positioned with the upper leg extended and the lower leg flexed. Adhesive tape may be used to secure the patient.

Monitor for venous air embolism (VAE) when the patient is positioned with the head above 20 degrees. VAE, a potentially life-threatening problem associated with the sitting operative position, is uncommon when the head is raised 20 degrees or less. The head is higher than the heart in the sitting position, and negative pressure is created in the dural venous sinuses and veins draining the brain and head. If air is introduced into the venous system, through the venous sinuses and/or cerebral veins, it is quickly carried to the right side of the heart, resulting in transient cardiovascular deficits or insufficiencies. Early signs of VAE are precordial Doppler sounds, increased end-tidal nitrogen (ETN2), and increased end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2). Late signs include a rise in CVP, pulmonary artery pressure, and pulse oximetry desaturation. Final signs are hypotension, tachycardia, cyanosis, and a mill-wheel murmur.6 When an air embolus is suspected, the surgeon is notified so that an

attempt can be made to identify and occlude the possible site of air entry. When the problem site has been occluded, the anesthesiologist can aspirate air through the central venous catheter using a 20-mL syringe and an airtight stopcock. If the entry site cannot be located, the patient is placed in the supine position, and the surgery is terminated.

Allows early detection of CNS ischemia so that care providers can intervene before irreparable damage occurs

Assists the surgeon to optimize treatment as dictated by monitoring parameters and their indication of the patients’ tolerance or response to surgical manipulation

TABLE 14-3 EFFECTS OF ANESTHETIC AGENTS ON CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW, CEREBRAL METABOLIC OXYGEN CONSUMPTION, AND INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IV agents

Barbiturates (thiopental)

Benzodiazepines (midazolam, lorazepam)

Sedatives (etomidate primarily for induction; dexmedetomidine)

Sedative hypnotic (propofol)

Narcotics (fentanyl, sufentanil)

Paralytics (succinylcholine primarily for induction; vecuronium, pancuronium)

Other (e.g., lidocaine suppresses laryngeal reflexes during intubation to blunt increases of ICP)

Inhalation agents that may impart some degree of cerebral protection

Isoflurane

Desflurane

Sevoflurane

Oxygen

space-occupying lesions with or without increased ICP.

cerebral aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, or cavernous angioma requiring clipping or excision.

carotid occlusion requiring extracranial vascular procedures, such as carotid endarterectomy or superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery bypass.

traumatic brain injury (TBI).

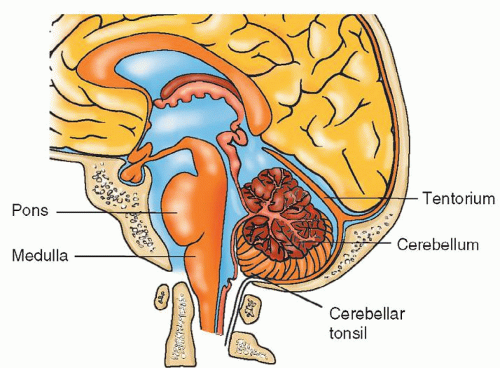

Surgery can be classified by anatomic location. Two terms differentiate the areas of the brain on which surgery is performed (Fig. 14-1):

The supratentorial area is above the tentorium and includes the cerebral hemispheres. The tentorium cerebelli is a double fold of dura mater that forms a partition between the cerebral hemispheres and the brainstem and cerebellum. The supratentorial approach is used to gain access to lesions of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

The infratentorial area is below the tentorium in the posterior fossa and includes the brainstem (midbrain, pons, medulla) and cerebellum. The infratentorial approach is used to gain access to lesions of the brainstem or cerebellum. Occasionally, temporal or occipital lobe lesions located close to the tentorial margin may be excised through the infratentorial approach.

A burr hole is created in the skull with a special drill that permanently removes a small circular area of bone. The burr hole may be

used to evacuate an extracerebral clot, to introduce a biopsy probe for isolated tissue sampling, or in preparation for craniotomy. In the case of a craniotomy, a series of burr holes are made for introduction of a special saw that cuts between the holes, allowing removal of the piece of bone or creation of a flap.

Figure 14-1 ▪ Surgery on the area of the brain above the tentorium is called supratentorial; surgery below the tentorium is infratentorial.

A craniotomy is a surgical opening of the skull to provide access to the intracranial contents for reasons such as removal of a tumor, clipping of an aneurysm, or repair of a cerebral injury. It involves creating a bone flap at the area over the lesion. The flap created is either a free flap or an osteoplastic flap. With a free flap, the bone is completely removed and preserved for replacement prior to completion of the case. With a bone flap, the muscle is left attached to the skull to maintain the vascular supply (Fig. 14-2).

A craniectomy is excision of a portion of the skull without replacement. This may be a permanent removal, such as with a suboccipital craniectomy where the bony skull is so thick that it requires meticulous chipping away of small pieces of bone while avoiding the underlying dura until an opening is created. There is no remaining bone flap to replace. In some cases, the surgeon may prefer to repair the skull defect by replacing the bone chips on a piece of Gelfoam before closing the muscle and skin.

A craniectomy may also involve saving the created free bone flap for replacement at a later date. The bone may be surgically implanted in the patient’s abdominal fat, or stored frozen at −80°C either in a hospital tissue freezer or a bone bank. Before the bone is stored frozen in the hospital tissue freezer or a bone bank, the bone should be cleaned, cultured, packaged with aseptic technique, and well labeled with patient’s identification information.

Craniectomies are performed to achieve decompression after cerebral debulking, as a life-saving measure during periods of maximal cerebral swelling to oppose herniation (e.g., following cerebral trauma, high-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage [SAH], or massive cerebrovascular accident [CVA]), or for removal of bone fragments from skull fracture.

Cranioplasty is the repair of skull to re-establish the contour and integrity of the cranial vault. This procedure involves replacement of a skull defect with synthetic material or replacement of the original craniectomy bone flap.

Microsurgery is defined as any surgery performed with the assistance of an operating microscope that provides magnification of small and delicate tissues. The surgical technique (microoperative technique), instruments (microinstrumentation), illumination for visualization, and magnification (operating microscopes), along with a host of other equipment, are specifically designed for this use. Surgical microscopes continue to evolve with new technology. Advances in optical, electrical, and mechanical technology have made it possible to design microscopes with enhanced precision and maneuverability. Figure 14-3 shows a surgical microscope that also allows the assistant to directly observe the operative field in high definition in three dimensions. Many microscopes attach to a video monitor, allowing others assisting in the OR to view the operative field. The latest model microscope is not only equipped with more advanced optical technology but also integrates the images from the stereotactic navigation guidance systems into the visual field of the surgeon. With the revolutionary fluorescence technologies built in the microscope, surgeons are now able to define accurate tumor margins seamlessly during removal of a malignant tumor tissue (Fig. 14-4) and evaluate the blood flow immediately after resection of an AVM or clipping of an aneurysm (Fig. 14-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree