Management of Fertility and Infertility

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the role of the nurse in helping couples choose contraceptive methods.

• Describe important considerations when choosing a contraceptive method.

• Explain why informed consent is important for contraception.

• Compare and contrast contraceptive needs of adolescent and perimenopausal women.

• Discuss the nurse’s role in contraceptive counseling and education.

• Explain factors that can impair a couple’s ability to conceive.

• Describe factors that can cause repeated pregnancy losses.

• Specify evaluations that may be performed when a couple seeks help for infertility.

• Discuss the nurse’s role for families needing care related to fertility or infertility.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Family planning involves choosing the time to have children. It includes contraception—the prevention of pregnancy—as well as methods to achieve pregnancy. This chapter discusses avoidance of pregnancy with contraception as well as help for couples with infertility or having difficulty achieving pregnancy.

Contraception

If both partners are fertile, approximately 90% of sexually active women who do not use contraception will conceive within 1 year (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Therefore those who wish to control the timing of pregnancies cannot leave contraception to chance.

Approximately 43 million women in the United States are sexually active and could become pregnant but do not want a pregnancy at this time. Of those women, 89% are practicing contraception (Alan Guttmacher Institute [AGI], 2010). However, they may not be using contraception consistently. A national survey of unmarried adults age 18 to 29 years found that although 86% of the men and 88% of the women did not want a pregnancy at the present time, 19% did not use contraception at all, and 24% used contraception inconsistently (Kaye, Suellentrop, & Sloup, 2009).

Unintended pregnancies are those that are unwanted or that occur in women who want to become pregnant at some time in the future but not at the time their pregnancy occurs. These pregnancies may result in economic hardship, health problems, interference with educational or career plans, and other disruptions in the lives of women and their families. Pregnancies that are spaced less than 6 months apart result in a higher risk for maternal mortality and morbidity, preterm birth, and low birthweight infants (Reinold, Dalenius, Smith, et al., 2009).

Three million unintended pregnancies occur each year in the United States (National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 2009). A Healthy People 2020 goal is to increase the number of pregnancies that are intended to 56% from a baseline of 51% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010).

Role of the Nurse

The nurse’s role in family planning is that of counselor and educator. To fulfill this role, nurses need current, correct information about contraceptive methods and need to share this information with the women they see in their practice.

Women who do not plan to become pregnant may have gaps in contraceptive use when there are changes in their relationships or when they are planning to change contraceptive methods. Approximately 40% of unintended pregnancies occur in women who used their contraceptive method incorrectly or inconsistently (AGI, 2008). This might occur less often if women had adequate ongoing education about their chosen method. Nurses can increase the likelihood of a woman using contraception by providing contraceptive counseling that is directed to the woman’s specific needs. Therefore the nurse must provide individualized family planning information to women in every situation in which it would be appropriate.

Nurses must be comfortable discussing contraception and be sensitive to the woman’s concerns and feelings. It is important that nurses do not introduce their own biases for or against specific methods. The nurse’s personal experiences and choices regarding contraception are not pertinent. Counseling must be focused on the needs, feelings, and preferences of the woman and her partner (Figure 31-1). For example, nurses working in maternity settings should discuss family planning with postpartum women to provide an opportunity to clarify misinformation and answer questions. Then the woman will be ready to discuss contraception further with her primary caregiver, if necessary.

Considerations when Choosing a Contraceptive Method

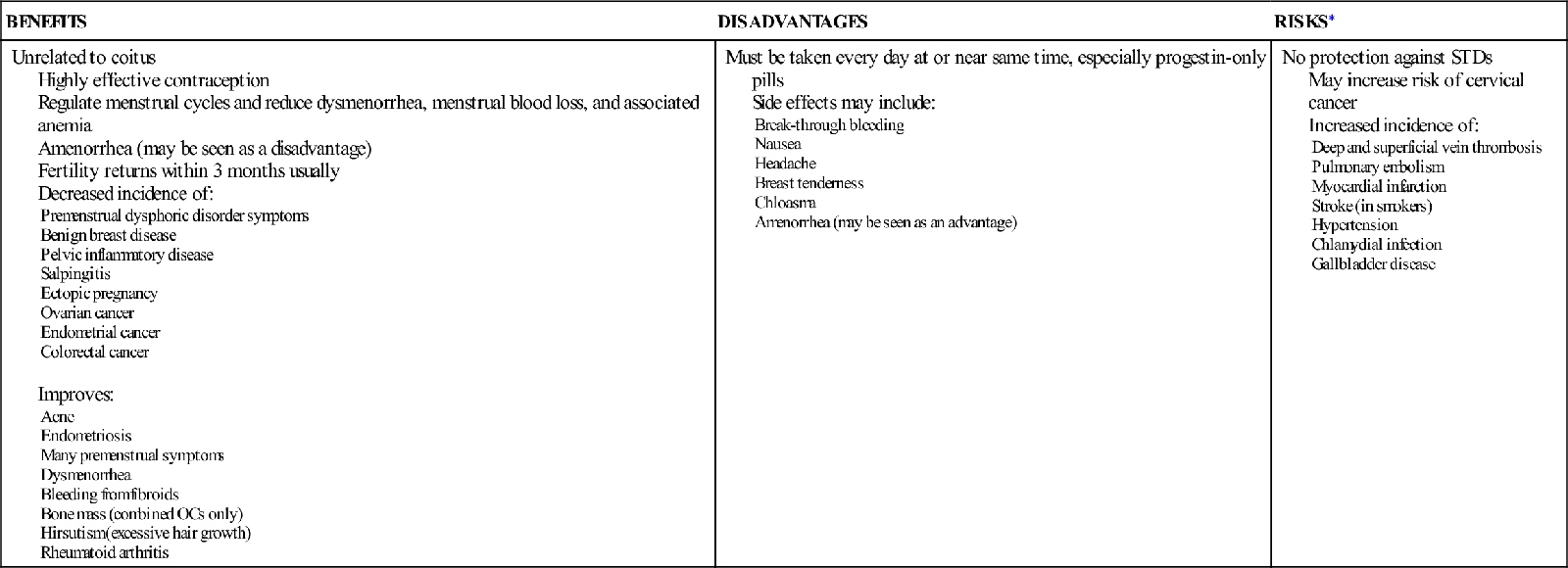

No contraceptive method is perfect. Each has advantages and disadvantages (Table 31-1). Sexually active women who do not want to become pregnant will need to use contraceptives for more than 30 years and are likely to change their contraceptive choices over that time. Women change contraceptive methods as circumstances in their lives change and in response to dissatisfaction with side effects or other traits of their contraceptive. Careful consideration of all factors can help women choose methods that best meet their needs and that they will use consistently.

TABLE 31-1

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF MOST COMMON CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS

| METHOD | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

| Sterilization | Ends concern about contraception Tubal sterilization performed during or right after childbirth or between pregnancies Vasectomy performed in the physician’s office with local anesthesia Low long-term cost | No protection against STDs Reversal is difficult, expensive, and may be unsuccessful Potential complications of any surgery Vasectomy requires another contraceptive method until semen is free of sperm Expensive initially |

| Intrauterine devices or intrauterine system | Unrelated to coitus In place at all times Low long-term cost Effective for 5 to 10 years Decreases dysmenorrhea and menstrual blood loss Some become amenorrheic Copper IUD may also be used for EC | No protection against STDs High initial cost Can be expelled without the woman’s knowledge—must check for strings Potential side effects or complications: menorrhagia, infection near time of insertion, perforation, ectopic pregnancy or spontaneous abortion if pregnancy occurs |

| Progestin implant | Unrelated to coitus Provides 3-year protection Safe during lactation Body weight has no effect Low long-term cost | No protection against STDs Minor surgical procedure to insert and remove Major side effect is irregular bleeding |

| Progestin injections (Depo-Provera) | Unrelated to coitus Avoids need for daily use May cause amenorrhea with continued use Requires use only every 12 weeks | No protection against STDs Must remember to repeat every 12 weeks Cause temporary decrease in bone density. Long-term effects unknown. Side effects similar to other progestin contraceptives |

| Oral contraceptives | Taken at time unrelated to coitus (see Box 31-1) | No protection against STDs Must be taken daily at or near same time May cause side effects and complications (see Box 31-1) |

| Emergency contraception (EC) | Helps prevent pregnancy after unprotected coitus Some available over the counter to patients 17 years and older | No protection against STDs Oral EC must be taken within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse May cause nausea |

| Transdermal contraceptive patch | Unrelated to coitus Requires only weekly application Regulates menstrual cycles | No protection against STDs Must remember to apply on the right day May be less effective for women over 90 kg (198 lb) May cause skin irritation Other side effects similar to OCs May have higher risk of clot formation |

| Vaginal contraceptive ring | Unrelated to coitus In place for 3 weeks at a time No fitting required | No protection against STDs Must remember when to remove and when to insert Side effects include expulsion, vaginal discomfort or discharge, and others similar to OCs |

| Barrier | ||

| All methods | Avoid use of systemic hormones Some offer some protection against STDs | Most coitus-related (must be used shortly before coitus) May interfere with sensation Contraindicated for allergies to components of spermicide or latex |

| Spermicides | Quick and easy No prescription needed Inexpensive per single use Provide lubrication | Films and suppositories must melt to be effective Effective time varies from less than 1 hour to 8 hours No douching for 6 hours May cause irritation May be messy New application needed for repeated intercourse |

| Condoms | Quick and easy No prescription needed Best protection available for STDs Inexpensive per single use Can be carried discreetly Vaginal condoms increase women’s control over contraceptive use and protection from STDs | Interfere with spontaneity Must be checked for expiration date and holes Can break or slip off Can be used only once Female condoms may seem unattractive |

| Sponge | Available over the counter Can be inserted several hours before coitus Effective for repeated intercourse No prescription needed | No protection against STDs Must remain in place for 6 hours after last intercourse but no more than 30 hours total May cause irritation Risk of toxic shock syndrome if used too long or during menstruation |

| Diaphragm | Can be inserted several hours before coitus Provides some protection from STDs Can remain in place up to 24 hours | Initially expensive; requires health care provider to fit Requires education on proper use Difficult to insert or remove for some women Added spermicide necessary for repeat coitus Possibility of toxic shock syndrome or bladder infection Must remain in place at least 6 hours after coitus |

| Cervical cap | Smaller than a diaphragm and may fit women who cannot wear a diaphragm No pressure against bladder Less noticeable than a diaphragm Can remain in place 48 hours Requires less spermicide Provides some protection from STDs | Initially expensive Requires health care provider to fit Requires education on proper use Added spermicide necessary for repeat coitus Possibility of toxic shock syndrome Must remain in place at least 6 hours after coitus |

| Natural Family Planning | ||

| All methods | Inexpensive No drugs or hormones Help a woman learn about her body Can be combined with barrier methods to increase effectiveness Acceptable to most religions May be used to help achieve pregnancy | No protection against STDs Requires high level of motivation and extensive education Requires abstinence for large part of each cycle High risk of pregnancy from error Many factors may change ovulation time |

IUD, Intrauterine device; OCs, oral contraceptives; STDs, sexually transmitted diseases.

The most popular methods of contraception in the United States are oral contraceptives (OCs), female sterilization, and male condoms (AGI, 2010). However, the most popular methods may not be right for every woman. Nurses can help women weigh factors involved in choosing a family planning method. Careful consideration of all factors helps women choose the method that best meets their needs.

Safety

The safety of the method is a primary consideration. Medical conditions may make some methods unsafe for certain women. For example, women who have had thrombophlebitis or stroke should not use OCs because the hormones may increase the risk for these conditions to recur.

Protection from Sexually Transmitted Diseases

No contraceptive (other than total abstinence) is 100% effective in preventing sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The risk of exposure to STDs should be discussed when counseling women about contraceptive choices. The male condom is inexpensive and offers the best protection available. It should be used whenever there is a risk that one partner may have an STD, even when another form of contraception is practiced or the woman is pregnant.

Effectiveness

The importance of avoiding pregnancy must be considered when choosing a contraceptive method. Effectiveness is determined by how often the method prevents pregnancy. Effectiveness rates reflect two different types of contraceptive failure. The ideal, perfect, or theoretic effectiveness rate refers to perfect use of the method with every act of intercourse. The typical, actual, or user effectiveness rate is most useful because it refers to the occurrence of pregnancy in real people using the method (Table 31-2).

TABLE 31-2

PREGNANCY RATES OF COMMON TYPES OF CONTRACEPTION: UNITED STATES

| METHOD | PREGNANCY RATE: ACTUAL OR TYPICAL USE (%) |

| Sterilization | |

| Vasectomy | 0.15 |

| Tubal sterilization | 0.5 |

| Intrauterine devices LNG-IUS (Mirena) Copper T 380A (ParaGard) | 0.2 0.8 |

| Contraceptive Implant | 0.05 |

| Injectable (Depo-Provera) | 6 |

| Oral contraceptives | 9 |

| Transdermal contraceptive patch (Evra) | 9 |

| Vaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing) | 9 |

| Spermicides, gel, foam, films, suppositories (used alone) | 28 |

| Condoms Male Female | 18 21 |

| Sponge Nulliparous women Parous women | 12 24 |

| Diaphragm with spermicide | 12 |

| Cervical cap Nulliparous women Parous women | 16 32 |

| Natural family planning (all types) | 24 |

| Coitus interruptus (withdrawal) | 22 |

| No contraceptive use | 85 |

Data from Trussell, J. (2011). Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception, 83(15), 307-404; Speroff, L., & Darney, P. D. (2011). A clinical guide for contraception (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Effectiveness drops greatly when the user does not understand how to use the method. The failure rate commonly decreases after the first year of use because experience with a method leads to more accurate use. Combining two less reliable methods, such as a condom and a spermicide, increases effectiveness.

Acceptability

The effectiveness of a method must be balanced against its acceptability to the couple. For example, a spermicide may be considered unacceptable because it seems “messy” to the woman. Teenagers who are not comfortable with their bodies are unlikely to be accepting of methods that require insertion of a device into the vagina. Although sterilization is very effective, it is not chosen by those who want to have more children. Side effects may cause some women to choose less-effective methods. The woman or her partner may be concerned about certain contraceptives because of perceived effects such as weight gain.

Convenience

Convenience is another important factor in choosing a contraceptive method. If the woman perceives her contraceptive as difficult to use, time-consuming, or too much “bother,” she is less likely to use it consistently. Methods that can be used monthly or weekly instead of daily or with each intercourse are more convenient and likely to lead to better compliance. Spotting or bleeding between periods, common with some methods, may be viewed as very inconvenient.

The desire to avoid monthly menstruation should also be considered. Some women prefer extended cycles with several months between menses, and others desire to avoid menstrual periods altogether. Extended or continuous use of OCs, the patch, and the ring may be used. Hormone implants or injections and intrauterine devices (IUDs)) may also lead to amenorrhea for some women.

Education Needed

Women may fail to use contraception because they do not understand their risk for pregnancy. They may be unfamiliar with the variety of methods available or the risks and benefits of the different types. Some methods, such as condoms, involve very little education, whereas others are more complicated. Women using natural family planning methods need extensive education to practice these methods successfully. Women knowledgeable about a contraceptive technique are less likely to feel that the contraceptive is difficult to use.

Benefits

Some methods have special benefits that should be discussed with women. OCs have many beneficial side effects such as improvement of acne, decreased bleeding with periods, or prolonged amenorrhea. Natural family planning methods offer freedom from exposure to hormones. Condoms provide better protection from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Side Effects

Many methods of contraception have bothersome side effects that should be explained. When women know what to expect, they are often more willing to tolerate side effects, especially if they know they do not indicate a health risk.

Effect on Spontaneity

Contraceptive methods related to coitus (sexual intercourse), such as spermicides and some barrier methods, must be readily available and used just before sexual intercourse. They interrupt love making, increasing the chance that the method will not be used. Some couples remedy this problem by making placement of the contraceptive device a part of foreplay. Others prefer methods such as OCs or IUDs that do not interrupt sexual activity.

Availability

Condoms and spermicides are readily available without prescriptions. They can be purchased anonymously at any time. Their availability may be important to an adolescent who wants to hide her sexual activity or to women who are embarrassed to discuss contraception with a health care provider.

Expense

The cost of family planning methods is important. Less-effective contraceptives are often chosen by some couples to save money. These methods may be less expensive, but more likely to result in pregnancy, which costs more than the yearly expense of any contraceptive method.

The “per use” cost of a contraceptive can be compared with long-term expense. The price of condoms and spermicides is relatively low, but frequent use makes them expensive over a period of years. Methods that depend on periodic visits to a health care provider are more costly than over-the-counter methods. However, these visits provide an opportunity for teaching about correct use that improves the contraceptive effectiveness. The visits also provide the woman an opportunity to discuss other health concerns. Long-term contraceptives such as IUDs are very cost-effective over a 5- or 10-year period because they prevent pregnancy so well.

Publicly funded clinics may provide free or low-cost contraceptives. However, many require a long wait, and the woman is likely to see a different health care provider each visit. The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nursing (2009) supports mandated insurance coverage for all U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved contraceptives as a way to prevent unintended pregnancies and reduce health care system costs.

Preference

The woman usually makes the final decision about her contraceptive method. Consistent use of any method depends on whether it meets the needs of the woman and her partner. If the woman feels pressured to choose a certain method or if a chosen method fails to live up to her expectations, use is more likely to be inconsistent. The opinion of the woman’s partner and her friends may also influence what method she chooses.

Religious and Personal Beliefs

Religious or other personal beliefs also affect the choice of contraceptives. For example, Roman Catholics may not believe in the use of any contraceptives other than natural family planning.

Culture

Another influence may be the woman’s culture. Some cultures place a high value on large families and especially on sons. A woman may have more pregnancies in an effort to have sons. Asian and Hispanic women are often very modest and do not talk about sexuality with others. They need to feel very comfortable with the nurse before talking about sexual matters. Taking time to establish rapport before discussing intimate subjects is important.

Some cultures restrict a woman’s activities during menses. Methods that have increased bleeding or break-through bleeding as a side effect may not be acceptable to these couples. Some African-American women believe that menses removes dirty or excess blood (Galanti, 2008). These women may not want to use contraception that increases or decreases bleeding.

Other Considerations

Women also consider other factors when choosing a contraceptive. The length of time before another pregnancy is desired will determine if a long-acting contraceptive is appropriate. Breastfeeding women must choose a method that will not harm the baby or reduce milk production. A woman at risk for acquiring or transmitting an STD should use condoms alone or with another, more effective, method of preventing pregnancy.

Obese women using combined OCs have a higher risk of thromboembolic disorders than nonobese women. However, the risk is less than that of pregnancy. Evidence is inconsistent as to whether effectiveness of OCs is less for obese women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010a).

Informed Consent

Because some methods have potentially dangerous side effects, it is necessary for the woman choosing surgical sterilization, hormone injections, implants, and IUDs to sign an informed consent form. Of course, whether or not a consent form is used, every woman should receive information about the chosen contraceptive method and its proper use, risks and benefits, and alternative methods available.

Adolescents

In a national survey of high school students, 46% reported ever having sexual intercourse, and 38.9% of currently sexually active students reported they had not used a condom at last sexual intercourse (CDC, 2010b). Although the rate of adolescent pregnancies has diminished in recent years, adolescent pregnancy is still a major problem. In 2009, there were 39.1 births per 1000 women 15 to 19 years old (Kochanek, Kirmeyer, Martin, et al., 2012). Because of the serious effect of pregnancy on the teenager, finding methods to enhance contraception use among adolescents is extremely important. (See Chapter 24 for more about adolescent pregnancy.)

The U.S. Healthy People 2020 goals include:

• Increasing condom use at first intercourse to 73.6% of adolescent females and 88.6% of males

• Increasing the number of sexually active adolescents ages 15 to 17 years who used a condom and hormonal or intrauterine contraception at first and last intercourse (USDHHS, 2010)

Adolescent Knowledge

Many adolescents have little knowledge about their own anatomy and physiology, including how and when conception occurs. They are likely to learn about contraception from other teenagers, who often pass on incorrect information. Contraceptive failure is twice as likely in teenagers as in women age 30 years or older (Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Misinformation

Misinformation and erroneous beliefs cause adolescents to use ineffective methods of contraception or no method at all. Even adolescent mothers are more likely to be inconsistent in contraceptive use or use ineffective methods. Some teenagers think they cannot become pregnant the first time they have intercourse. Others assume they must have an orgasm or must have been menstruating a certain length of time to become pregnant. Conception, however, can result from any intercourse near ovulation. Although many adolescents have anovulatory menstrual cycles during the early months after menarche, they cannot depend on failure to ovulate to prevent pregnancy because some will ovulate before their first menses.

Teenagers and older women may douche (insert a solution into the vagina) after intercourse to prevent pregnancy. However, douching is ineffective because sperm may enter the cervix very soon after ejaculation. Coitus interruptus (withdrawal of the penis before ejaculation) is another unreliable method used by teenagers. It requires more control over timing of ejaculation than most adolescent boys have. In addition, semen (sperm and fluid discharged during ejaculation) spilled near the vagina can enter and cause pregnancy even without penetration by the penis.

Risk-Taking Behavior

Adolescents are more likely than adults to take risks in sexual activity because they believe their chances of becoming pregnant are low. Because of their immaturity and feelings of invincibility, teenagers often do not plan intercourse and are not prepared with contraceptives. They are more likely to engage in risk-taking behavior than older women, and this may lead to STDs and pregnancy. Some teenagers wait months after becoming sexually active to begin contraception.

Counseling Adolescents

Nurses who counsel adolescents about sexuality must be sensitive to their feelings, concerns, and needs (Figure 31-2). They must be accepting of the teenager regardless of personal feelings about adolescent sexuality. Teenagers may not ask about contraception because they do not want anyone to know they are sexually active. Their need for secrecy may cause them to miss family planning appointments. The nurse must reassure teenagers that their visits are confidential.

Visits to a health care provider for checkups, minor illnesses, or pregnancy testing can provide unplanned opportunities for the nurse or other health care provider to discuss contraception. After a negative pregnancy test, a teenager may be particularly interested in learning about contraception.

Although nurses should encourage adolescents to discuss contraception with their parents, many teenagers will forego contraception rather than talk to their parents about it. Therefore, they need other reliable sources of information. Many schools provide information about sexuality. Discussions include information about contraception as well as abstinence. Encouragement to delay sexual activity and discussion about the effect of pregnancy on the adolescent are often included. Family planning clinics that are open after school and in the evenings may also be a source of contraception education and supplies.

The pelvic examination, greatly dreaded by many women, is not necessary for a prescription for OCs and may be delayed until a later health care visit. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that yearly Papanicolaou (Pap) tests should begin within 3 years of the first vaginal intercourse or by age 21, whichever is first (ACS, 2011). During the first contraceptive visit, the teenager receives information about contraceptive methods. Taking the time to explain the different methods may help dispel misinformation and allay common concerns.

Because of her youth and possible lack of knowledge about anatomy and physiology, the adolescent often needs more extensive teaching than the older woman. Liberal use of audiovisual materials, such as pictures, anatomic models, and samples of various methods, helps the teenage girl understand the information more easily. Giving her a patch, vaginal ring, and condom to manipulate or showing her the packet of pills she will be using are important aids.

Adolescents have most success when they choose contraceptive methods that are easy to use and that seem unrelated to coitus. The most popular contraceptives for adolescents are OCs and condoms (Speroff & Darney, 2011). Teenagers choose OCs because they are safe, have few contraindications for teenagers, seem unrelated to sex, and are not difficult or messy. In addition, they increase bone density, regulate periods, may decrease acne, and reduce menstrual flow and cramping (Cunningham et al., 2010; Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Adolescent girls may be inconsistent in taking pills every day, however. They are more likely than older women to discontinue any method for side effects such as spotting. Their concerns should be taken seriously, and attempts made to alleviate side effects so they will continue using the method. Methods that do not have to be used every day may be more appropriate for teens who tend to forget their pills or do not like the side effects of OCs.

Adolescents may use condoms alone to prevent pregnancy and STDs, especially at the beginning of a relationship or with casual partners. With long-term partners, they may switch from condoms to hormonal methods. Increased use of hormonal methods is associated with decreased use of condoms for many adolescents. Some seldom use condoms except if they have casual partners or if they are very concerned about pregnancy and STDs. Many young women are uneasy about asking a partner to use a condom. Discussions about how to negotiate condom use with a partner are helpful. Using a condom and an OC provides highly efficient contraception along with protection from STDs and should be encouraged.

Perimenopausal Women

Pregnancy is uncommon after age 50. However, perimenopausal women may continue to ovulate as long as they have regular menstrual periods, and some ovulate even when indications of menopause are present. Fertility begins to decline when women reach 35 to 40 years, but they are still at risk for an unintended pregnancy (Nelson, 2011). In fact, more than 30% of pregnancies in women older than age 35 years are unintended (Godfrey, Chin, Fielding, et al., 2011).

One study found that 14% of women ages 35 to 44 years did not use a contraceptive at last intercourse, and women ages 40 to 44 years failed to use contraception at last intercourse twice as often. The study also found that women who received contraceptive counseling in the past year were 80% more likely to use contraception (Upson, Reed, Prager, et al., 2010). Therefore, the nurse must offer these women contraceptive counseling whenever possible. To avoid pregnancy, effective contraception should be used until 1 year after a woman’s last menses (Barry, 2011).

The most common method used by women in the United States who are older than 30 years is sterilization (AGI, 2010). Low-dose OCs may be used by nonsmokers to provide contraception and help regulate the irregular bleeding that often occurs during perimenopause. However, women older than age 35 years who smoke or have significant cardiac risk factors should not use combined hormonal contraceptives (CDC, 2010a). Barrier methods or contraceptives that contain only progestin (any form of progesterone), such as the progestin IUD (Mirena), Depo-Provera, or progestin only OCs, are also good choices for the older woman. Perimenopausal women should have regular physical examinations to identify any conditions that would require a change in contraceptive method.

Methods of Contraception

Sterilization

Sterilization (male and female combined) is the most widely used contraception in the United States. Approximately one in three married couples uses this method (Beckmann, Ling, Barzansky, et al., 2010). Although it is expensive at the time of surgery, sterilization ends all further contraceptive costs. It should always be considered a permanent end to fertility because reversal surgery is difficult, expensive, not always successful, and often not covered by insurance.

Couples considering sterilization need counseling to ensure that they understand all aspects of the procedure. When surgery is planned for immediately after childbirth, the decision should be made well before labor begins. Future marriage, divorce, or death of a child may cause couples to regret their decision. Although pregnancy is rare after sterilization, the risk of failure should be discussed. Pregnancies that occur after tubal sterilization are more likely to be ectopic.

Tubal Sterilization

Tubal sterilization (also called tubal ligation) is widely used throughout the world. It involves cutting or occluding the fallopian tubes to prevent fertilization. The surgery is easiest during abdominal surgery such as cesarean birth when a woman is sure that she wants the procedure regardless of the outcome of the birth. During the first 48 hours after vaginal birth, the fundus is located near the umbilicus, and the fallopian tubes are directly below the abdominal wall, making this a good time for tubal sterilization. Interval tubal sterilization, not associated with childbirth, is often performed as outpatient surgery. General anesthesia is most common, but regional or local anesthesia may be used.

There are various surgical methods for tubal sterilization. A minilaparotomy incision may be made near the umbilicus during the postpartum period or just above the symphysis pubis at other times. Surgery also can be performed through a laparoscope inserted through a small incision. In each method, the surgeon blocks the tubes with clips, bands, or rings, removes a piece of the tubes and ties the ends, or uses electrocoagulation to destroy a portion of the tubes.

Two nonsurgical methods of sterilization exist. Essure involves the insertion of a small coil through the vagina and uterus into each fallopian tube. The Adiana system involves radiofrequency energy to remove a thin layer of tissue and insertion of a silicone implant in each tube. The procedures can be performed in the physician’s office. The tubes become permanently blocked during the next 3 months as tissue grows in and around the inserts. During this time, another contraceptive method is necessary. A hysterosalpingogram is performed at the end of 3 months. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2010c) emphasizes the importance of the hysterosalpingogram at 3 months to ensure the tubes are completely blocked.

Vasectomy

Vasectomy, the male sterilization procedure, involves making a small incision or puncture in the scrotum to cut, tie, cauterize, or remove a section of the vas deferens, which carries sperm from the testes to the penis. After vasectomy, sperm no longer pass into the semen.

Vasectomy is safer, easier, less expensive, and has a lower failure rate than tubal sterilization (Speroff & Darney, 2011). It can be performed in a physician’s office under local anesthesia and is less expensive. After surgery, the man rests and wears a scrotal support for 2 days. He applies ice to the area for 4 hours and takes a mild analgesic, if needed. Strenuous activity should be avoided for 1 week (Roncari & Hou, 2011).

Sperm may be present in the ductal system, distal to the ligation of the vas deferens when the surgery is performed. The couple should understand that the man may be able to impregnate a woman until sperm are no longer present in the semen, which may be 3 months or more. He should submit semen specimens for analysis until two specimens show no sperm present.

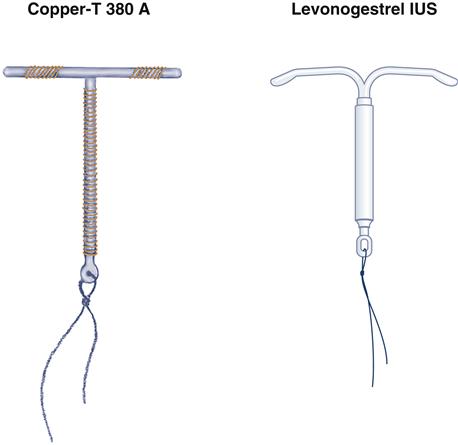

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)

An IUD is inserted into the uterus to provide continuous pregnancy prevention. The Copper T 380A (ParaGard) and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS or Mirena) are shaped like the letter T (Figure 31-3). ParaGard is effective for 10 years and Mirena for 5 years. Fertility returns when the device is removed. Increased usage of IUDs is recommended by ACOG as a long-term, cost-effective means of lowering unintended pregnancy (ACOG, 2009).

Many women have misperceptions regarding the safety and effectiveness of IUDs (Hladky, Allsworth, Madden, et al., 2011). Although there was a concern about safety with early models, IUDs are considered very safe at this time. More education about IUDs is necessary to increase their use. IUDs provide contraception without the need to take pills, have injections, or perform other tasks just before intercourse. They may be inserted immediately postpartum or after an abortion although expulsion is higher in the immediate postpartum period (ACOG, 2009).

IUDs can be used by some women who cannot use other hormonal contraception. They are safe for adolescents and women who have never had a baby. There is a slight risk of infection during the first 20 days after insertion, but there is no increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease or infertility in women who use IUDs or when couples are not mutually monogamous if condoms are used (ACOG, 2009; Memmel & Gilliam, 2008). Women at high risk for STDs should use another method.

Action

IUDs cause a sterile inflammatory response resulting in a spermicidal intrauterine environment. They do not cause abortion (Speroff & Darney, 2011). The copper-covered ParaGard produces a spermicidal uterine environment. Progestin is continuously released from the LNG-IUS, Mirena. The progestin causes decreased sperm and ova viability, thickening of the cervical mucus barring sperm penetration, inhibits sperm motility, prevents ovulation some of the time, and makes the endometrium hostile to implantation.

Side Effects

Side effects include cramping and bleeding with insertion. Menorrhagia (increased bleeding during menstruation) and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation) are common reasons for removal of the copper device. Ibuprofen may relieve cramping and reduce bleeding. Irregular bleeding or spotting may occur during the early months with the LNG-IUS, but bleeding is less than with the copper IUD and may be followed by amenorrhea. The LNG-IUS may be used for women who had menorrhea before using an IUD.

Complications include expulsion of the IUD and perforation of the uterus. Although pregnancy with an IUD is rare, ectopic pregnancy or spontaneous abortion is more likely if pregnancy does occur. Infection may occur in the first few weeks after insertion because of contamination at the time of insertion. Women with recent or recurrent pelvic infections, a history of ectopic pregnancy, bleeding disorders, or abnormalities of the uterus should choose another contraceptive method.

Teaching

Teaching the woman about side effects and to check for the presence of the plastic strings, or “tail,” extending from the IUD into the vagina is important. The woman should feel for the strings once a week during the first 4 weeks, then monthly after menses, and if she has signs of expulsion (cramping or unexpected bleeding). If the strings are longer or shorter than they were previously, she should see her physician, nurse-midwife, or nurse practitioner. The health care provider should be informed about signs of infection, such as unusual vaginal discharge, pain or itching, low pelvic pain, and fever. Any signs of pregnancy should be reported to rule out ectopic pregnancy and remove the device if pregnancy has occurred.

Hormonal Contraceptives

Hormonal contraceptives alter the normal hormone fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. Hormones may be delivered by implant, injection, patch, or vaginal ring, or can be taken orally.

Hormone Implant

The progestin implant, Implanon (or Nexplanon), a single rod implant, is inserted subcutaneously into the upper inner arm. Implanon is 2 mm thick and 4 cm (1.6 in) long and releases progestin continuously to provide 3 years of contraception. Like other progestin-only contraceptives, it inhibits ovulation, thickens cervical mucus to prevent sperm penetrability, and makes the endometrium unfavorable for implantation. Increased usage of hormone implants is recommended by ACOG as a means of offering effective long acting reversible contraception (ACOG, 2009).

Side effects include irregular menstrual bleeding. The woman should be taught that bleeding is expected and not a sign of abnormality. Amenorrhea may occur with longer use. Implanon is safe during lactation, body weight does not affect effectiveness, and fertility returns within a few weeks when the implant is removed. If it is inserted within 7 days of the start of menses, no back-up method is needed. If it is inserted later, a back-up contraceptive should be used for at least 3 days (Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Hormone Injections

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, or DMPA (Depo-Provera), is an injectable progestin that is available in an intramuscular (IM) and a subcutaneous (Sub Q) form. It is convenient, has no estrogen, and prevents ovulation for 14 weeks although injections should be scheduled every 12 weeks. Action and side effects are similar to those of other progestin contraceptives. Women who should not use other hormone contraceptives should avoid Depo-Provera as well.

The IM form of Depo-Provera is given by deep intramuscular injection. The Sub Q form is given in the anterior thigh or abdomen. The site should not be massaged after injection because massage accelerates absorption and decreases the period of effectiveness. A back-up method of contraception should be used for the first 7 days unless the injection is given within 5 days after a menstrual period starts. Back-up contraception is also recommended if the woman is more than 2 weeks late in returning for subsequent injections, and a pregnancy test may be performed.

Menstrual irregularities are the major reason for discontinuation. Although spotting and break-through bleeding are common, amenorrhea occurs in 80% of women using the IM form at 5 years and at 1 year for 55% of women using the Sub Q form (Speroff & Darney, 2011). Other side effects include breast tenderness, weight gain, headaches, depression, and decreased bone density.

Because of the loss of bone density that occurs with prolonged use, the prescribing information states that Depo-Provera should not be used for longer than 2 years unless no other contraceptive is suitable. Although bone density losses are reversed after the drug is discontinued, it is not known if the bone loss is fully reversible. It may be more of a problem for women who begin Depo-Provera during adolescence or in the perimenopausal period. The World Health Organization considers the advantages of use of Depo-Provera in adolescents younger than age 18 years to generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks (CDC, 2010a). Women who use Depo-Provera should get adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D and should increase weight-bearing exercises.

Depo-Provera can be started in the immediate postpartum period, and it increases the quantity of milk in lactating women. The effectiveness is not changed by a woman’s weight. There is a delay in return to fertility after the drug is discontinued. Approximately 59% of women resume menses in 6 months, and 25% do not resume menses for a year or more (Beckmann et al., 2010).

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives are a widely used reversible contraceptive method in the United States. They are available as combination OCs containing both estrogen and progestin or as minipills that contain only progestin. Both types have much lower hormone levels than the original OCs, thus decreasing the risk of long-term side effects.

Progestin Only

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are less effective at inhibiting ovulation, but avoid the use of estrogen, which cannot be used by some women. POPs cause thickening of the cervical mucus to prevent penetration by sperm, and they make the endometrial lining unfavorable for implantation. The woman should start POPs during the first 5 days of her menstrual cycle and take one pill at the same time of day continuously. She can start the pills on another day if she is sure she is not pregnant. If she misses any pills or does not take them at the same time each day, chances of pregnancy increase. The woman should use a back-up method of contraception for 2 days when the pills are first started, if she is more than 3 hours late in taking a pill, or has vomiting or diarrhea within 4 hours of taking a pill (Raymond, 2011). Break-through bleeding and greater chances of error have made these OCs less popular than the combination OCs.

Combination

Combined OCs (COCs) containing estrogen and progestin are the most common OCs. COCs suppress estrogen and luteinizing hormone (LH), which inhibits maturation of the follicle and ovulation. They cause thickening of the cervical mucus, preventing sperm from entering the fallopian tubes. In addition, tubal motility is slowed, and the endometrium becomes less hospitable to implantation.

Monophasic or multiphasic dosages are available. Monophasic pills have an estrogen and progestin content that remains constant throughout the cycle. With multiphasic pills, the estrogen and progestin levels vary at different times of the cycle to help reduce side effects. Because of the dosage changes phases, women must take the pills in the proper order.

Many COCs are available in packets of 21 or 28 tablets. With 21-tablet packets, the woman takes 1 pill daily for 3 weeks and then stops for a week, during which menses occurs. Packets of 28 tablets include 21 active tablets and 7 tablets made of an inert substance that the woman takes during the fourth week. These extra pills avoid disrupting the everyday routine of taking pills. Some formulations contain 24 active tablets with 4 inactive tablets. Women using them have shorter, lighter withdrawal bleeding.

Some women prefer extended cycles in which menses is delayed for a few days for special occasions or for a longer time. These women take two or more pill packs without taking the placebo pills for several packs or indefinitely. A COC designed to provide 84 days of active pills and seven placebo pills or seven pills with a small amount of estrogen allows women to have menses only four times a year. The added estrogen is given to decrease breakthrough bleeding and give a shorter withdrawal bleed. Another formulation is taken every day without stopping to suspend menstrual periods indefinitely. Breakthrough bleeding and spotting are a common problem with extended or continuous use, but they usually lessen with time. A disadvantage is that a woman might not recognize an early pregnancy if it occurred.

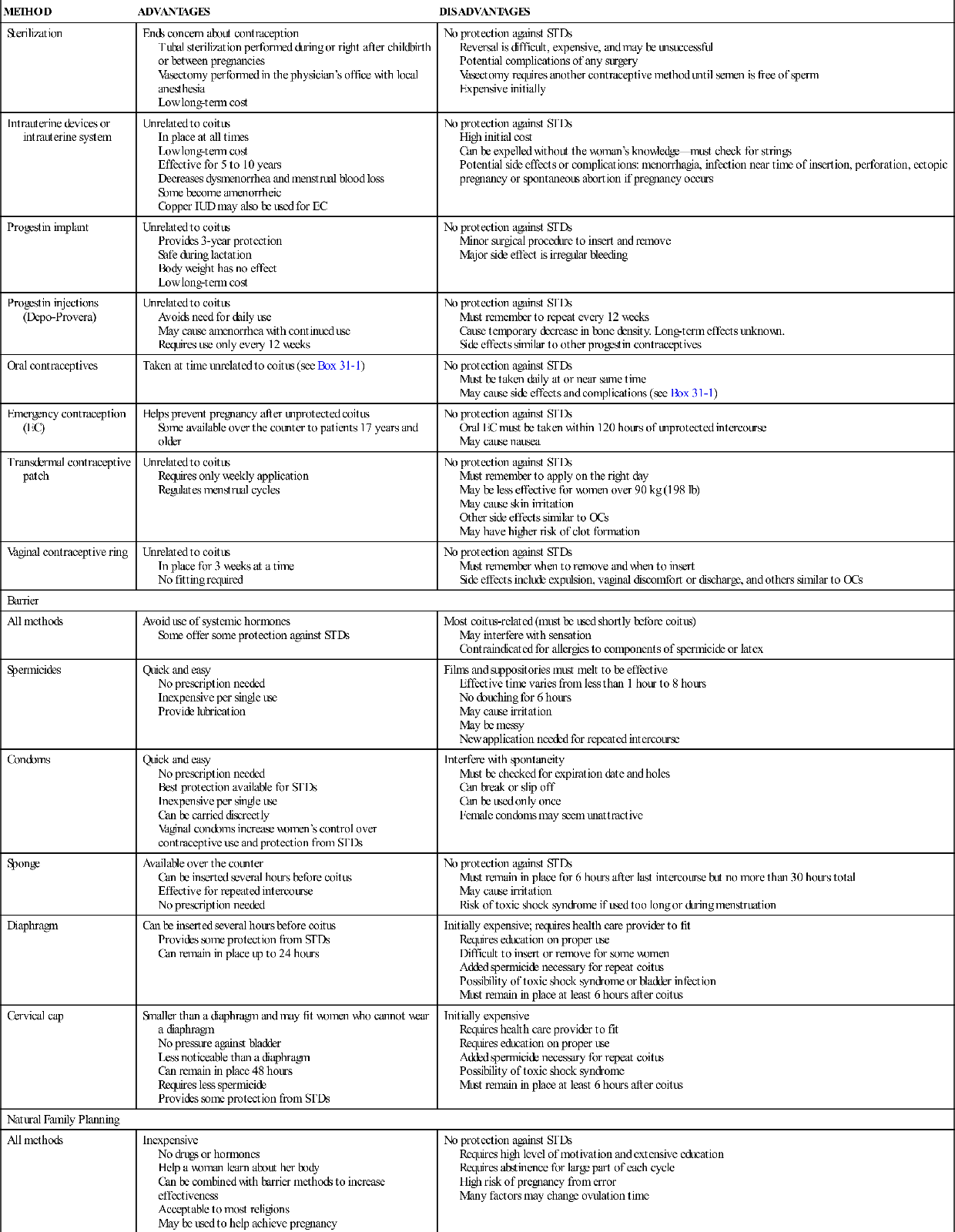

Benefits, Risks, and Cautions

When choosing OCs, the balance between the benefits and risks must be weighed for each individual (Box 31-1). Women often believe the risks of OCs are higher than they are, yet taking OCs are safer for most women than pregnancy (Beckmann et al., 2010). In addition to safe, reliable contraception, OCs result in regular menses and decreased flow, premenstrual syndrome, and dysmenorrhea, reduced acne, and improved bone density.

OCs should not be used by women who have certain medical complications (see Safety Alert: Cautions in Using Oral Contraceptives). Smoking significantly increases complications for women of all ages. Women older than age 35 who smoke should not use OCs. Women who have previously smoked must abstain from all sources of nicotine for at least 6 to 12 months to be considered a nonsmoker (Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Obese women have a higher risk of thromboembolic problems, but this is not considered to be a contraindication to OC use. Evidence is inconsistent about whether body weight affects OC effectiveness (CDC, 2010a). Women with diabetes of less than 20 years duration, who do not smoke, and are in good health may use OCs with adequate supervision of their condition (CDC, 2010a). OCs provide no protection against STDs and may increase susceptibility to chlamydia. A woman should be advised to use a condom and spermicide if her partner may be infected or the relationship is not monogamous.

Side Effects

Approximately 33% of women who do not wish to become pregnant discontinue OCs within a year, (Trussell, 2011) usually because of side effects. Most side effects are minor. Using formulations with less estrogen helps relieve nausea and breast tenderness. Break-through bleeding occurs most often in the first 3 months and then usually subsides. Some women complain of weight gain while taking OCs, but studies have not shown it to be caused by the pills (Beckmann et al., 2010). Other side effects include fluid retention, amenorrhea, and melasma (brownish pigmentation of the face).

Teaching

Many unintended pregnancies result from failure to take OCs correctly. However, education about proper use greatly increases effectiveness. Because the instructions can be complicated, the woman should receive written as well as verbal instructions in her own language if she can read.

Teaching about when to start taking OCs is especially important. The woman may be told to start taking her pills on the day they are prescribed, if it is reasonably sure she is not pregnant (Quick Start method), on the first day of the next menstrual period, or on the first Sunday after her next menses begins. The Quick Start method provides immediate protection. A Sunday start prevents the woman from having periods on weekends. Unless she begins her pills on the first day of her menses, the woman is usually told to use a back-up contraceptive for the first week.

One study showed that women who did not fully understand the advantages of OCs and had low confidence in their ability to use them were less likely to continue use at 6 months (Dempsey, Johnson, & Westhoff, 2011). The nurse should listen carefully to women’s concerns about side effects and help them find methods of relief. Teaching about temporary side effects may help the women endure them until they are no longer present.

When women discontinue OCs because they are unhappy with the side effects, they may not use another contraceptive or may use one that is less effective and become pregnant as a result. Women should be instructed to keep a back-up contraceptive method readily available should they decide to stop taking their OCs.

Blood Hormone Levels

Maintaining a constant blood hormone level is important for effectiveness, especially with POPs. The woman must take the pills near the same time each day. Many women make them a part of their morning or bedtime routine. The pills can be taken with a meal to avoid nausea. Illness may affect the blood hormone levels. A woman who experiences vomiting or diarrhea should use a back-up method of contraception for 7 days because the hormones may not have been properly absorbed.

Missed Doses

The woman should follow instructions from her provider if she misses one or more doses of her OC. Instructions vary according to the type of OC she uses, the number of doses missed, and the time in the cycle the OC is missed.

Instructions for missed OCs commonly include (Speroff & Darney, 2011):

If a woman misses a period and thinks she may be pregnant because she missed one or more doses, she should stop taking the pills and get a sensitive pregnancy test immediately. It is essential that she use another contraceptive method during this time. Although an association with significant fetal anomalies has not been established, continued use of OCs during pregnancy is not advisable.

Postpartum and Lactation

Women have an increased risk of thrombosis after giving birth. They are usually advised to wait 3 to 4 weeks to begin COCs (CDC, 2011b; Nelson & Cwiak, 2011). COCs reduce milk production in lactating women, and small amounts may be transferred to the milk. POPs are a better choice because they do not decrease milk production and in fact may increase it. They may be started immediately after delivery (Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Other Medications

OCs may interact with other medications. Drugs that stimulate metabolism in the liver, such as St. John’s wort and some anticonvulsants may change the effectiveness of OCs. Most broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals do not decrease OC effectiveness (CDC, 2010a). The woman should always tell any health care provider and her pharmacist about other drugs she is taking.

Follow-up

The only essential follow-up for women who take OCs is yearly blood pressure measurement. It is not necessary for women to have yearly pelvic examinations, Pap tests, or breast examinations to receive prescriptions for OCs. Women should follow the same recommendations for these examinations as women who do not take OCs.

The woman’s ability to remember to take a pill every day should be evaluated, and other methods should be discussed if this is a problem. Return of fertility usually occurs within 3 months after the pills are discontinued in women who were ovulating before pill use (Cunningham et al., 2010). Any signs of adverse reaction should be reported immediately. Use of the word ACHES may help the woman remember signs that may indicate complications (Table 31-3).

TABLE 31-3

ACHES∗

Warning Signs of Oral Contraceptive Complications

| WARNING SIGN | POSSIBLE COMPLICATION | |

| A | Abdominal pain (severe) | Mesenteric or pelvic vein thrombosis, benign liver tumor, gallbladder disease |

| C | Chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, cough | Pulmonary embolism or myocardial infarction |

| H | Severe headache, weakness or numbness of extremities, hypertension | Stroke, migraine |

| E | Eye problems (complete or partial loss of vision, headache) | Stroke, migraine, retinal vein thrombosis |

| S | Severe pain or swelling, heat, or redness of calf or thigh | Deep vein thrombosis |

∗The acronym ACHES can be used to help women remember warning signs that may indicate complications when using oral contraceptives. Other signs include jaundice, a breast lump, and depression. The woman should contact her health care provider if any of these signs develop.

Data from Nelson, A. L. & Cwiak, C. (2011). Combined oral contraceptives (COCs). In R. A. Hatcher, J. Trussell, A. L. Nelson, et al. Contraceptive technology (20th ed., pp. 249-341). New York: Ardent Media.

Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception (EC; also called the “morning-after pill”) is a method to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. This method may be used after contraceptive failure, such as a condom breaking during intercourse; after rape; or in situations when contraceptives were used incorrectly or not at all.

Two forms (Plan B One-Step and Next Choice) of EC contain the progestin levonorgestrel. They are available at pharmacies without a prescription for women who are 17 years of age and older with a picture identification for proof of age. Those younger than 17 years need a prescription. Another form of EC is ulipristal acetate (Ella), which requires a prescription for all ages.

The progestin ECs delay or inhibit ovulation and interfere with corpus luteum function (Fontenot & Harris, 2008). They are effective if ovulation has not already occurred. The treatment is ineffective if implantation has already occurred. It does not harm a developing fetus (Speroff & Darney, 2011; Trussell & Schwarz, 2011). Ulipristal acetate (Ella) acts to delay or block the luteinizing surge and ovulation. It may also inhibit implantation (Nichols, 2010). Pregnancy should be excluded before Ella is taken because it can interfere with an existing pregnancy.

EC involves taking one or two tablets (taken together) that contain a high dose of progestin. Treatment reduces the risk of pregnancy by about 85% (Speroff & Darney, 2011). Combined OCs in larger-than-usual doses can also be used for this purpose. The dose varies with the brand and may require taking a large number of tablets. EC is most effective if used as soon as possible within 72 hours of intercourse but may be used with lessened effectiveness within 120 hours. Ulipristal acetate (Ella) can be taken within 5 days of unprotected intercourse. EC will not prevent pregnancy if unprotected intercourse occurs after EC is used.

Insertion of the copper IUD within 5 days of intercourse may also be used and is up to 99% effective (Trussell & Schwarz, 2011). Mifepristone may also be used for EC. The drug inhibits ovulation and prevents endometrial development. However, mifepristone will disrupt an existing pregnancy. Because it is also used for medically induced abortion, some women will prefer to use another method.

Many women are unaware of the availability of EC. One survey found that although most female college students had heard of EC, many had inaccurate knowledge about the action, side effects, and how to obtain it (Hickey, 2009). Information about its use and how to obtain it should be included any time education about contraception is offered. Information about EC is available at www.not-2-late.com or www.ec.princeton.edu. Women who need EC should receive counseling about their regular contraceptive method. They may not understand how to use their method correctly or may wish information about other, more effective options. Because of the short time during which EC is effective, some health providers give women prescriptions to use at a later date, if needed. Women who use EC have not been shown to be more likely to have risky sex, future unplanned pregnancies, or STDs (Sander, Raymond, & Weaver, 2009).

Transdermal Contraceptive Patch

The ethinyl estradiol and norelgestromin transdermal contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra) releases small amounts of estrogen and progestin that are absorbed through the skin to suppress ovulation and make cervical mucus thick. It also regulates menstrual cycles. A nonhormonal contraceptive should also be used during the first week of use unless the patch is started on the first day of the menstrual period.

The patch is applied to clean, dry, nonirritated skin of the abdomen, buttock, upper torso (excluding the breasts), or upper outer arm. It should not be placed over areas where lotions or oils have been used or where the patch would be rubbed by clothing. A new patch is applied to a different site on the same day of the week each week for 3 weeks and worn continuously for 7 days. No patch is worn during the fourth week. During the patch-free week, the woman has a period. After 7 patch-free days, she applies a new patch and begins the cycle again. Women can have extended cycles without menses by using patches for several cycles or continuously. Patches should not be cut or altered, and no more than one patch should be worn at a time.

The patch usually adheres to the skin even in the shower or when exercising or swimming. However, about 5% of patches detach (Speroff & Darney, 2011). A patch should be replaced by a new patch if it cannot be reattached. Extra patches are available by prescription. The day the patch is changed does not change even if a replacement for a detached patch is necessary. If a patch is detached for more than 24 hours or there is a delay of more than 2 days within the cycle, a new patch is applied to start a new cycle. The patch change day will be the day of the week the new patch is applied. Back-up contraception is necessary for 1 week of the first cycle (Speroff & Darney, 2011).

Side effects include spotting, especially during the first two cycles, breast tenderness, and skin reactions. Other side effects and risks are similar to combination OCs. The patch may be less effective in women who weigh more than 90 kg (198 lb) (Nandra, 2011). The risk of venous thromboembolism may be higher with patch use than with OC use because the estrogen exposure is 60% higher over time when patches are used. However, studies have had conflicting results (Cunningham et al., 2010). Women with risk factors for thromboembolic conditions should discuss the risks and benefits of patch use with their health care provider.

Contraceptive Vaginal Ring

Women using the ethinyl estradiol contraceptive ring (NuvaRing) insert a soft, flexible ring into the vagina and leave it in place for 3 weeks (Figure 31-4). The ring releases small amounts of progestin and estrogen continuously to prevent ovulation. The woman removes the ring at the end of the third week, and bleeding occurs. A new ring is inserted to begin the next cycle a week after the old ring was removed. Although a prescription is required, no fitting or particular placement in the vagina is necessary. Unless the ring is inserted on the first day of menses, a back-up contraceptive should be used during the first 7 days of the first cycle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree