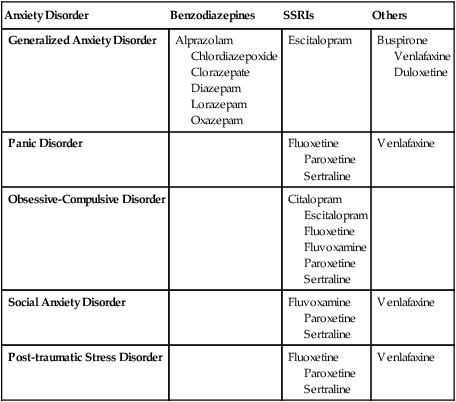

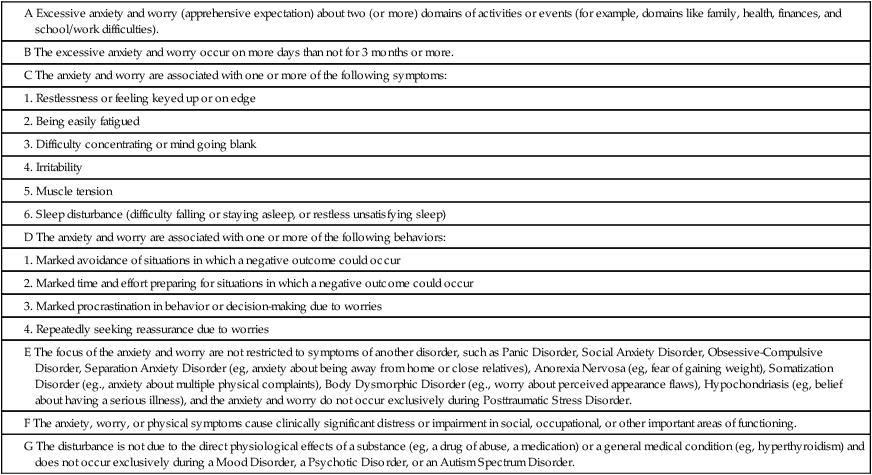

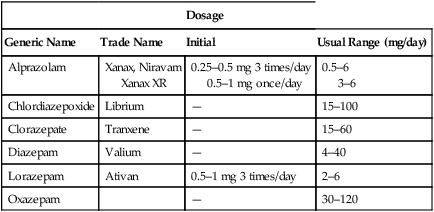

CHAPTER 35 As indicated in Table 35–1, two classes of drugs are used most: benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Benzodiazepines are used primarily for one condition: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). In contrast, the SSRIs are now used for all anxiety disorders. It should be noted that, although SSRIs were developed as antidepressants, they can be very effective against anxiety—whether or not depression is present. TABLE 35–1 First-Line Drugs for Anxiety Disorders The hallmark of GAD is unrealistic or excessive anxiety about several events or activities (eg, work or school performance) that lasts 6 months or longer. Other psychologic manifestations include vigilance, tension, apprehension, poor concentration, and difficulty falling or staying asleep. Somatic manifestations include trembling, muscle tension, restlessness, and signs of autonomic hyperactivity, such as palpitations, tachycardia, sweating, and cold clammy hands. Diagnostic criteria for GAD, as proposed for DSM-5, are shown in Table 35–2. TABLE 35–2 Proposed DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder Modified from the proposed diagnostic criteria for GAD, to be published in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Expected publication date: May 2013. Copyright © American Psychiatric Association. The proposed criteria are from the DSM-5 web site—www.DSM5.org—accessed on November 11, 2011. Benzodiazepines are first-choice drugs for anxiety. As discussed in Chapter 34, benefits derive from enhancing responses to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Onset of benefits is immediate, and the margin of safety is high. Principal side effects are sedation and psychomotor slowing. Patients should be warned about these effects and informed they will subside in 7 to 10 days. Because of their abuse potential, benzodiazepines should be used with caution in patients known to abuse alcohol or other psychoactive substances. Of the 13 benzodiazepines available, 6 are approved for anxiety. The agents prescribed most often are alprazolam [Xanax, Xanax XR, Niravam] and lorazepam [Ativan]. However, there is no proof that any one benzodiazepine is clearly superior to the others. Hence, selection among them is largely a matter of prescriber preference. Dosages for anxiety are summarized in Table 35–3. TABLE 35–3 Dosages of Benzodiazepines Approved for Anxiety The basic pharmacology of the benzodiazepines is discussed in Chapter 34. • Palpitations, pounding heart, racing heartbeat • Sensation of shortness of breath or smothering • Nausea or abdominal distress • Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint • Paresthesias (numbness or tingling sensations) • Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (feeling detached from oneself) • Fear of losing control or going crazy

Management of anxiety disorders

Anxiety Disorder

Benzodiazepines

SSRIs

Others

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Alprazolam

Chlordiazepoxide

Clorazepate

Diazepam

Lorazepam

Oxazepam

Escitalopram

Buspirone

Venlafaxine

Duloxetine

Panic Disorder

Fluoxetine

Paroxetine

Sertraline

Venlafaxine

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Citalopram

Escitalopram

Fluoxetine

Fluvoxamine

Paroxetine

Sertraline

Social Anxiety Disorder

Fluvoxamine

Paroxetine

Sertraline

Venlafaxine

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Fluoxetine

Paroxetine

Sertraline

Venlafaxine

Generalized anxiety disorder

Characteristics

Treatment

Benzodiazepines

Dosage

Generic Name

Trade Name

Initial

Usual Range (mg/day)

Alprazolam

Xanax, Niravam

Xanax XR

0.25–0.5 mg 3 times/day

0.5–1 mg once/day

0.5–6

3–6

Chlordiazepoxide

Librium

—

15–100

Clorazepate

Tranxene

—

15–60

Diazepam

Valium

—

4–40

Lorazepam

Ativan

0.5–1 mg 3 times/day

2–6

Oxazepam

—

30–120

Panic disorder

Characteristics

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of anxiety disorders

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue