Chapter 24 Maintaining continence

Continence

Acquiring urinary continence

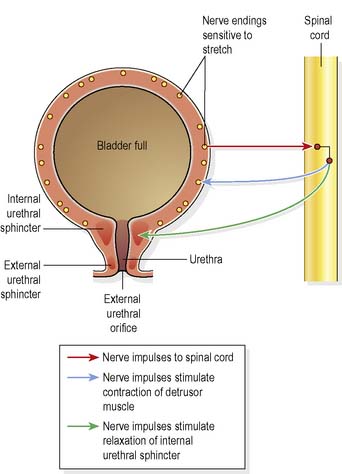

The neurological control of the bladder at birth involves a simple sacral reflex arc whereby automatic filling and emptying of the bladder are under the control of some sacral segments of the spinal cord. Nerve endings in the bladder wall are activated by stretch as urine accumulates. These relay impulses with increasing frequency through the parasympathetic nerves to the spinal cord until the motor parasympathetic nerve impulses cause the bladder muscle to contract and the urethral sphincters to open, whereupon reflex emptying occurs (Figure 24.1).

Figure 24.1 Reflex control of micturition when conscious effort cannot override the reflex action.

(Reproduced from Waugh & Grant 2006 with permission.)

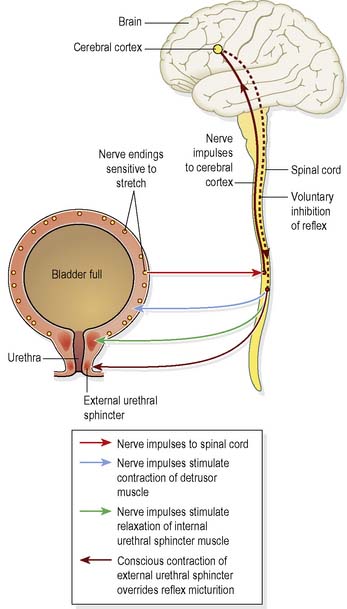

In order to achieve continence, a child needs to become aware of the sensation of bladder filling and through trial and error attempt to overcome the reflex emptying mechanism by using the pelvic floor muscles to keep the urethral sphincter closed. Sensory impulses from the bladder travel in the spinal cord to the cerebral cortex, whereupon motor impulses from the cerebral cortex travel to the bladder to inhibit the bladder contractions; this requires practice as well as maturation of the central nervous system. Continence thus involves the active inhibition of nerve impulses. When micturition is initiated, the brain ceases to initiate inhibitory impulses, allowing the spinal reflex arc to be completed. Figure 24.2 illustrates the control of micturition once bladder control is established.

Figure 24.2 Control of micturition after bladder control has been established.

(Reproduced from Waugh & Grant 2006 with permission.)

Attitudes towards loss of continence

The psychosocial implications of incontinence are far-reaching. Social exclusion is common, as individuals with incontinence are often afraid to leave home, afraid they may be unable to access a lavatory in time, or experience an episode of incontinence in the presence of others. This can lead to depression. In older people this may contribute to a loss of mobility and can be a cause of falls (Teo et al 2006).

It is important for nurses to examine their own attitude towards bladder, bowel and continence care. It has been found that some nurses consider routine or service requirements to be more important than assisting people to use the lavatory (Morrow 2002, Nazarko 2003).

Urinary incontinence

The International Continence Society (ICS) (2002) has coordinated the publication of a consensus document defining the terminology associated with the lower urinary tract, in which it defines urinary incontinence as ‘a condition in which involuntary loss of urine is a social or hygienic problem’. However, it is only when the specific type and cause of the person’s incontinence are known that appropriate treatment can be offered.

The prevalence of urinary incontinence in the UK is difficult to ascertain. Some estimates suggest that between 3 and 6 million people have some degree of urinary incontinence. Interestingly, the Bladder and Bowel Foundation (2008a) estimates that around one third of women are affected by stress urinary incontinence.

It is recognised that although urinary incontinence affects all age groups, male and female, its prevalence is greatest amongst women, particularly older women. In response to this fact the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2006) developed guidelines on the management of urinary incontinence in women.

Types and causes of urinary incontinence

Overflow incontinence

occurs as a consequence of urinary retention, which may in turn result from:

Enuresis

refers to any involuntary loss of urine. Nocturnal enuresis is the term for urinary incontinence that occurs during sleep, in the absence of organic disease or infection (not to be confused with nocturia, which is being woken at night by the urge to pass urine). Enuresis may be primary or secondary. The number of adults afflicted with nocturnal enuresis is uncertain, due to the hidden nature of the problem, although Hjalmas et al (2004) quote the prevalence of enuresis as 0.5% in otherwise healthy adults aged 18–64. There are three conditions that may contribute to enuresis, often in combination:

Faecal incontinence

According to NICE (2007), faecal incontinence is a not a diagnosis but is a symptom or sign. Reaching a consensus on a definition of faecal incontinence is difficult, but it can be classified by the symptom, such as faecal leakage. The prevalence of faecal incontinence in the UK is difficult to ascertain as it remains a taboo subject and people are reluctant to discuss their problems or seek help, due to embarrassment, anxiety and fear. It is estimated that faecal incontinence is experienced by 1–10% of the adult population living at home (NICE 2007). However, prevalence rates vary, from up to 13% for minor incontinence in the community, to up to 95% in nursing homes (Black 2007). It is known that faecal incontinence is more common in older people, particularly frail older women.

Faecal incontinence, like urinary incontinence, is a symptom of an underlying pathology and with appropriate assessment and treatment many people will regain continence (Kenefick 2004).

Types and causes of faecal incontinence

Causes of faecal incontinence in adults include:

Rao (2004) states that many people who experience faecal incontinence refer to themselves as having diarrhoea or urgency as this seems more tolerable. Rao refers to faecal incontinence being graded in relation to its severity:

Faecal incontinence or soiling in children is termed ‘encopresis’ and is defined as the passage of a normal consistency stool in a socially unacceptable place. The prevalence of children with faecal incontinence decreases from 1 in 30 children at age 5 years to 1 in 100 by the age of 12 years (Department of Health [DH] 2000).

Epidemiology of incontinence – prevalence studies

Seminal research into the prevalence of incontinence by Thomas et al (1980) found that whilst incontinence was most prevalent among older women, its occurrence was significant across all age groups. Stress incontinence was reported less often by nulliparous than by parous women of all ages, and was especially prevalent among those who had borne four or more children. Urge incontinence also occurred more commonly among parous than nulliparous women. No significant class differences were found among men or women, but individuals of African Caribbean or part African Caribbean descent were more likely to have some form of incontinence than those of Asian descent.

An audit of first assessments by community nurses found that district nurses were primarily assessing people with incontinence for absorbent products rather than assessing their incontinence with a view to improved management or regaining continence (Audit Commission 1999). There is a need not only to identify people who are incontinent, but also to improve public and professional understanding of incontinence, to evaluate services available for those requiring assessment and to improve methods of treatment and management (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] 2004). However, continence care seems to remain low on the list of nursing priorities, with a focus on containment rather than interventions to improve continence and QoL (Box 24.1).

Box 24.1 Evidence-based practice

Do nurses promote continence in hospitalised older people? An exploratory study

Activities

Sociological factors in underreporting of incontinence

That incontinence remains to such a large extent a hidden problem among the general population can be attributed in part to the embarrassment felt by many people, leading to reluctance to admit to incontinence and seek treatment (Mason et al 2001). Several authors agree that the more severe the incontinence, the more likely a person is to seek medical help (Roe et al 1999, Shaw 2001). However, the severity of the symptoms is only one factor that influences the person in their choice to seek professional help or not. Shaw (2001) identifies other factors that influence this decision:

Many people prefer not to mention their incontinence to others (Roe et al 1999).

Personal and social attitudes towards incontinence are not, however, the only factors that account for the underreporting of this widespread health problem. The way that particular health services are marketed or presented can also influence an individual’s decision whether to seek help or cope on their own. In the words of one person, ‘I would find it too embarrassing to go to a special clinic…perhaps a home visitor would be more helpful’ (Association for Continence Advice 2000).

It is therefore important that continence services reflect positive attitudes and approaches to promoting continence, and progress on this is demonstrated in the setting of standards by nurses and monitoring of services and treatment. It is vital that people and carers affected by incontinence are given every opportunity to regain their continence, to be empowered and to be involved in the development of targeted services. To this end, a Charter for Continence was developed by several professional organisations in 1995 (Box 24.2). Various government initiatives and other publications have assisted in the process.

Box 24.2 Information

Charter for Continence

As a person with bladder or bowel problems you have the right to:

In England and Wales, the DH (2000) issued guidance on continence services to the NHS. This provided targets for both inpatient and community care. The guidance also influenced the content of the 10-year programme of the National Service Framework (NSF) for older people (DH 2001). A supporting system redesign for older people is now underway to build on the progress of the NSF (DH 2009). The Essence of Care (DH 2010) benchmark statements ensured that specific areas of care, such as continence, could be audited and improved.

In Scotland, various guidance was published, for example, NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHSQIS) (2004), Nursing and Midwifery Practice Development Unit (NMPDU) (2002) and SIGN (2004).

In the last few years NICE has produced guidelines for both urinary and faecal incontinence and related treatments (NICE 2006, 2007).

Factors contributing to incontinence

Delay in achieving continence

In childhood, the acquisition of the skills necessary to achieve continence may be delayed. Nocturnal enuresis may present as a primary or secondary feature; its cause is not known. Although it often spontaneously resolves, it is sometimes not resolved during childhood. In such cases, if it remains untreated, it may be a problem throughout life (Hjalmas et al 2004). Its impact on both individual and family has been researched by Morrison et al (2000).

Learning disability may also prevent a person from attaining continence. Professionals working with people who have learning disabilities should base their interventions on the assumption that, although the process of toilet training may be slow, continence will eventually be achieved provided interventions are tailored to the individual and their family’s requirements (Rogers 1998). Physical difficulties can hinder the acquisition of continence. Some children cannot become continent without medical intervention, such as in some types of spina bifida. An infant or child who is continuously wet should always be investigated for either congenital fistula or failure to empty the bladder. Such symptoms should be taken seriously as failure of bladder emptying (with stasis of urine) can lead to vesicoureteric reflux (VUR). There is reflux of urine up the ureters following a rise of pressure within the bladder during voiding. The urine later runs back to the bladder and is not immediately voided, which in turn increases the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI). The constant reflux of infected urine into the ureters can lead to chronic pyelonephritis (reflux nephropathy) (see Ch. 8).

Factors affecting existing continence

A number of factors can affect continence. These include:

Physical factors

Age

While incontinence is more prevalent among older people (especially women), it is not an inevitable consequence of growing older. However, with normal ageing comes a decline in renal function; it is reduced by up to 50% by the age of 80 years, thus impairing the ability of the kidney to concentrate urine. This consequence of ageing occurs alongside a decrease in the bladder’s urine-storing capacity (Hald & Horn 1998).

Ignoring the urge to urinate or defecate

Ignoring the need to empty the bladder may lead to an episode of incontinence of urine, whilst ignoring the need to defecate may lead to constipation. Constipation is a common contributing factor to urinary incontinence and also retention of urine (see p. 670). Because of the anatomical proximity of the rectum and the urethra, it is possible for the urethra to be closed off by a faecal mass. This can result in incomplete voiding and stasis of urine, which in turn can encourage growth of bacteria and UTI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree