CHAPTER 22 Maintaining body temperature

Introduction

Normal body temperature

The temperature of the tissues of the body

Surface temperature

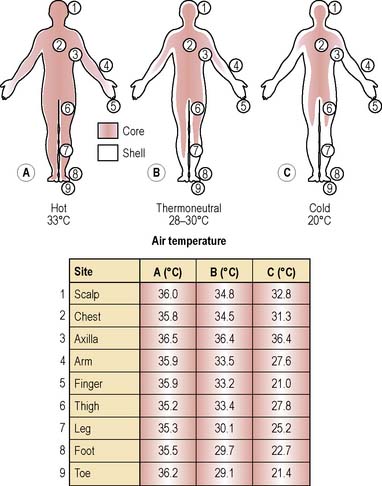

Under most circumstances, the skin surface or ‘body shell’ is the coolest part of the body. The organs, blood and deeper tissues are described as the body ‘core’ (Tortora & Derrickson 2006). Because the temperature of the skin is influenced by the temperature and humidity of the air (Figure 22.1), measurement of skin temperature is not a reliable method to detect temperature changes of the organs and deep body tissue (Box 22.1). This may be most important when caring for patients with critical illness where accurate temperature measurement is likely to be of importance in the diagnosis of infection.

(Based on an original figure by Aschoff & Wever, cited in Stainer et al 1984, with additional data from Childs C.)

Deep body (core) temperature

The organs of the head and thorax (the main components of core tissues), e.g. heart, liver and brain, are ‘insulated’ from environmental conditions by bone, fat and skin. The liver, kidneys, brain and myocardium have a high metabolic rate and consequently a higher temperature than tissues with a lower rate of metabolic activity such as smooth muscle and skin (Houdas & Ring 1982).

In a recent publication by Moran et al (2007) the authors undertook a prospective observational cohort study to investigate whether tympanic measurements were a reliable measurement technique in the critically ill patient. Different conventional methods for body temperature measurement were compared. Access the paper by Moran and colleagues on the website to find out whether the authors considered tympanic membrane temperature to be a valuable measurement method in critically ill patients.

See website Research abstract 22.1 for information about a study by LeFrant et al (2003) that demonstrated the variation in core temperatures in the different organs, muscles, etc.

Regulation of body temperature

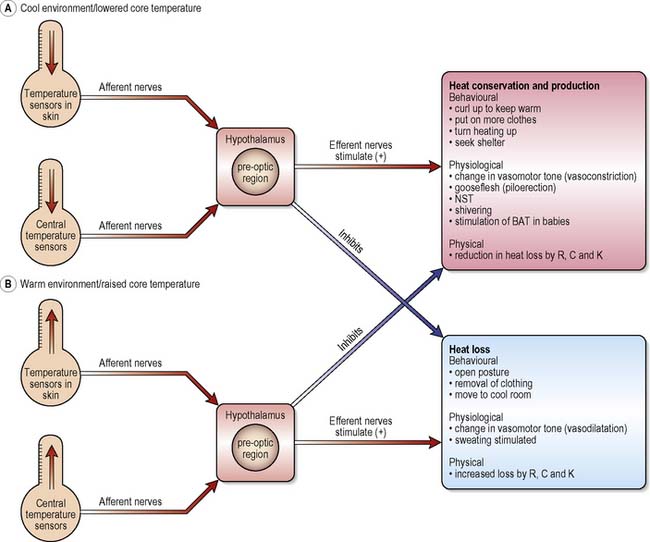

Mammalian thermoregulation is controlled by the brain, specifically the pre-optic region within the anterior portion of the hypothalamus (POAH) (see website Figure 22.1 for anatomy of the hypothalamus). Incoming (afferent) signals to the hypothalamus from thermoreceptors in skin and organs are transmitted to and integrated within the POAH, which then responds by transmitting outgoing (efferent) signals to the body so that heat can be either generated/conserved or lost.

For example, if the temperature of the blood bathing the cells of the hypothalamus starts to rise above ‘normal’ (37°C), as in a fever, the outgoing, or efferent, signals stimulate ‘effector’ mechanisms so that heat is lost from the body. Conversely, if the incoming blood is at a lower temperature than the reference (set-point) temperature (i.e. <37°C), mechanisms to conserve or produce heat will be activated. In this way, deep body temperature is prevented from rising or falling from the biological set-point of 37°C. The pathways that help to maintain body temperature at a constant level are shown in Figure 22.2.

Mechanisms of heat conservation and heat production

Heat production

In a healthy young adult, metabolic rate is between 35 and 39 kcal/m2 body surface/h whereas in an infant, metabolic rate is 53 kcal/m2 body surface/h. The fact that an infant has a higher metabolic rate than an adult can be explained by the rapid synthesis of cells in the growing body. However, in both adults and children, metabolic rate may rise well above the normal limit for a given age if the person is sick or injured. The most well recognised explanation for a rise in metabolic heat production is the onset of a fever (Childs & Little 1994, Jenney et al 1995) after an injury such as a burn.

In early studies, patients suffering from serious burns (see Ch. 30) were found to have a very high metabolic rate and also a very high body temperature (Childs 1994). Wilmore (1977) reported that metabolic heat production in severe burns was almost double that of a healthy person of the same age. Later, it was found that improvements in surgical management, wound care and analgesia ameliorated the enormous increases in metabolic rate and demand for energy (Childs 1994) although patients remained febrile. Part of the high metabolic ‘cost’ of burn injury could be reduced by early surgery (to promote healing of the burn wound) and pain management but fever can persist and is a cause of raised metabolic rate, especially if the patient develops a burn wound infection.

Any activity or event that increases the rate of chemical reactions in cells and the rate of oxygen uptake by the cell increases metabolic rate and thus the amount of metabolically produced heat (Frayn 1997). Body heat is produced in two ways: chemically by non-shivering thermogenesis, and physically by the rhythmical contractions of skeletal muscle, i.e. shivering thermogenesis.

Shivering thermogenesis

People who are cold shiver. The heat conservation area of the brain stimulates mechanisms that increase muscle tone, i.e. shivering, such that heat production increases to five times the basal rate. Shivering occurs in most skeletal muscles but the greatest intensity of shivering thermogenesis is in the jaw and neck and is least in the legs. The repetitive contraction of muscle is not, however, a very economical process, as only 40% of the heat generated during shivering is retained by the body and shivering does not continue indefinitely (see Hypothermia, p. 627).

Mechanisms of heat loss

High air temperature and strenuous exercise will raise the temperature of the blood. If the heat gained during the exercise is not matched by an equivalent rate of heat loss, heat-losing mechanisms are initiated and heat-conserving mechanisms are inhibited (Figure 22.2). The series of events that protects the brain and core tissues from reaching dangerously high temperatures is as follows:

Table 22.1 Principles of heat transfer

| Route for Heat Loss | Principle | Relevance to Clinical Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Radiation (R) | Transfer of energy in the form of electromagnetic waves. The human body emits heat as infrared radiation. At the same time all dense objects (furniture, buildings, other people) are also radiating heat. The rate at which heat is emitted from the human body is dependent upon the temperature difference (gradient) between the skin and other objects and surfaces in the room. If the skin is hotter than the average temperature of objects in the room, heat will be lost. If the objects in the room are hotter, the body will gain heat | A person, naked, sitting quietly in a room at 25°C loses between 50 and 70% of heat by R, the major route for heat loss under such conditions. As air temperature increases, the temperature gradient between skin and air falls such that less heat is lost by this route. As air temperature rises towards skin temperature (35°C), the gradient will be so small that very little heat loss can take place by this route. Evaporative heat loss then becomes an important route for heat loss |

| Convection (C) | Air (or water) next to the body warms and moves slowly away because warm air is less dense and rises. As it moves away from the body, cooler air replaces it. This process can be speeded up if a strong draught (e.g. electric fan) is used to force the air away and cause a rapid replacement of warmed air with cool air | Nurses frequently increase the rate of heat loss by convection by placing electric fans close to their patients. This can be a very efficient way to lower skin temperature, but frequently the cool stimulus results in an inappropriate response, i.e. peripheral vasoconstriction. Heat retention within core tissues can cause core temperature to rise rather than fall. In febrile patients who have an elevated set-point, the use of electric fans is likely to cool the skin and return heat to the tissue |

| Conduction (K) | Heat loss by K involves transfer of thermal energy from atom to atom. The skin must be in contact with cooler or hotter objects for heat exchange to take place by K | Critically ill patients are often nursed on special beds designed to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. These beds are often maintained at a constant temperature to help prevent heat loss from the body. Sometimes the thermostat can fail and patients have been known to overheat or to cool because the temperature of the bed is too high or too low. Patients must be protected from body temperature disturbances of such an iatrogenic nature |

| Evaporation (E) | Evaporation of water from the skin and respiratory passages is the most important route for heat loss in hot conditions. The evaporation of water occurs when energy transforms water and sweat droplets to a gas. The heat (or thermal energy) needed to drive this process is taken from the body. Thus the more water there is on the skin, the more heat is taken from the body to turn it into a gas (vaporisation). The more heat removed from the body in the process of E, the more the body cools. The function of sweat (produced under the control of the sympathetic nervous system) as an agent for vaporisational heat loss can be enhanced by spraying the body with a fine mist of warm water | Patients with a high core temperature may not always sweat. During a rise in rectal temperature the body responds as though it were too cold and if patients are observed carefully it will be seen that their skin is dry. At this stage the hypothalamic set-point is above normal but the body continues to activate heat-conserving mechanisms to achieve the new set-point temperature. Only when the patient has reached the new central temperature set-point will heat loss by all routes (E included) be activated. Thus when nurses notice that patients with a high core temperature are sweating, it is more likely to indicate that core temperature has reached the new set-point. A fall in body temperature may then follow |

Fluctuations in a healthy person’s temperature

Normal temperature range

Website Figure 22.2 illustrates the range of ‘normal’ temperature in health.

Circadian rhythm

In general, the lowest temperatures recorded over a 24-h cycle will be approximately 0.5°C lower than the afternoon temperature. By the evening, body temperature may be as much as 1.0°C above the early morning temperature. In the newborn, a circadian rhythm of core temperature is not fully developed (Waterhouse et al 2000).

Other factors affecting a healthy person’s temperature

Babies and young children

As long ago as 1937, Bayley & Stolz showed that rectal temperature begins to rise during the first 7 months of life, remaining fairly constant until the age of 2 years, after which it begins to fall. Average rectal temperature at age 1 month was reported to be 37.1–37.2°C, at 8 months 37.6–37.7°C, and at 18 months 37.7°C. By the time the children in the Bayley & Stolz study approached their third birthday, rectal temperature had settled to 37.1°C.

To counteract increased heat loss, babies have an important source of body heat: brown adipose tissue (BAT), a specialised type of fat cell (Cannon & Nedergaard 2004). BAT is a unique type of adipose tissue, shown by Hull (1976) to be an important source for heat production in small hibernating mammals, and has been described as the ‘hibernating gland’. BAT is also stimulated in the human newborn infant after birth. Under the control of the sympathetic nervous system, the function of BAT is to transfer energy from food into heat (Cannon & Nedergaard 2004) and probably plays a role in the evolutionary success of mammals. BAT can be found around the kidneys, between the shoulder blades, around the great vessels and deep within the axillae (Frayn 1997). BAT is richly supplied with blood and oxygen and this dense blood supply is responsible for its brown colour. It becomes much less important in maintaining the temperature of the body as a baby gets older. In adults, BAT is scarce and probably not functional (Klaus 2004).

Adults and older people