CHAPTER 23

Lymphedema

Patricia A. Lewis

M. Eileen Walsh

OBJECTIVES

1. Describe normal lymphatic flow.

2. Identify criteria used to diagnose primary and secondary lymphedema.

3. Describe medical and surgical management of lymphedema.

4. Discuss nursing interventions related to patient teaching, disease prevention, home care and self-care.

Introduction

Lymphedema is swelling of a body part due to the accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid or lymph in the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Mohler & Mondry, 2013). Lymphedema most often affects an extremity, but it may develop in the face or head, chest wall, abdomen, pelvis, or genitalia. Lymphedema is caused by imbalances in the microcirculation or disruptions that result in an inability of the lymphatic vessels to adequately transport lymph fluid back to the central circulation. The process is characterized by nonpitting edema and predisposes an individual to recurrent infections, such as lymphangitis and cellulitis. It is important to distinguish lymphedema from other forms of edema, such as venous stasis or dependent edema secondary to heart failure.

The world-wide incidence of lymphedema is estimated at over 150 million, with more than 1% Americans affected (Felty & Rooke, 2004), although the true incidence may be higher due to under-reporting and nonrecognition by both patients and health care providers. “Accurate estimates of the incidence of lymphedema are difficult to find because of

• The lack of a standard clinical definition of the condition

• Very few consistent surveys have appeared in the literature

• The occurrence of lymphedema is so dependent on the patient’s genetic predisposition to develop the condition

• The patient’s general health and lymphatic system health, including the nature and extent of lymphatic trauma” (Weiss, 2007).

Lymphedema can result from a congenital anomaly, dysfunction, or from an acquired disease. Primary lymphedema refers to cases of unknown etiology or congenital abnormality; secondary lymphedema refers to cases with a known cause such as infection, trauma, malignancy, or surgery. Filariasis caused by a parasite is the most common cause of lymphedema world-wide, and affects more than 100 million people. In nonindustrialized countries, the most common cause of lymphedema is cancer and cancer therapy (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000).

The natural course of the disease is a progressive increase in the size of the affected body area over the lifetime of the individual. Chronic lymphedema can be a cosmetic deformity as well as a disabling condition. Although lymph vessels and nodes were first mentioned in medical literature dating back to Hippocrates and Aristotle, it has long been a neglected topic in medicine until recent advances in physiologic investigation have led to improvements in diagnosis and management (Gloviczki, 2000). There is no cure for lymphedema; however, therapeutic interventions can lessen the degree of swelling and aide in preventing progression and complications.

I. Anatomy and Normal Lymphatic Function

I. Anatomy and Normal Lymphatic Function

A. Lymph Fluid

1. Clear, colorless fluid

2. Formed by transudation of fluid into tissue spaces

3. Composition

a. Protein: approximately half of all proteins are transported from interstitium into systemic circulation via lymph flow every 24 hours

b. Water: serves as transport medium for cellular products

c. Cellular components: varies depending on location; includes white blood cells/lymphocytes, cancer cells, bacteria, viral cells, cellular debris from phagocytosis, and protein breakdown

d. Fatty acids: lipids are absorbed by intestinal tract travel via lymphatics to enter blood circulation; fats and other digestive byproducts cause a milky appearance of lymph fluid or chyle in mesenteric system. Approximately 4 to 5 lbs are produced every 24 hours

4. Lymphocytes circulate to fight infection

5. Lymph fluid is filtered through lymph nodes, which remove bacteria, debris, and chemicals

B. Lymphatic System: recognized in 18th century as an integrated system responsible for absorption by Drs. William and John Hunter (Gloviczki, 2000)

1. Lymphatic vasculature: main function is to transport interstitial fluid and protein lost from the capillary system; transport infectious material and debris, back into venous circulation

a. Initial lymphatics (also called terminal, superficial, or capillaries) (Foeldi, 2012)

1) Found in skin and mucus membranes, blind-ended sinuses lined by single layer of lymphatic endothelial cells

2) Located in all tissues and organs except CNS and cornea

3) Structure similar to venous capillary except for

a) Presence of large openings between cell junctions in capillary

b) Openings allow fluids and large solutes (proteins) to enter capillary

c) Overlapping design creates one-way valve: allows entry of fluids and proteins, but substances cannot flow back out

d) Opening of flaps stimulated by variations in tissue pressure and contraction of fibrils attached to exterior cell walls and surrounding connective tissue (Kelly, 2002)

b. Lymphatic pre-collectors

1) Thicker: less permeable but still capable of absorption

2) Valves expedite movement of fluid from superficial capillaries toward deeper transport vessels

c. Lymphatic ducts: also known as collectors, lymphatics, or valved vessels

1) Carry lymph toward trunk, run parallel to deep arteries and veins

2) Walls contain contractile smooth muscle similar to veins but have thinner walls and valves at shorter intervals

3) Two major collecting channels

a) Superficial (epifascial) system: collects 80% of fluid from skin and subcutaneous tissue. In lower extremity, this system has 10 to 15 large lymphatic channels located mainly along greater saphenous vein

b) Deep lymphatic system: drains subfascial structures (bone, muscles, deep blood vessels); follows tibial, popliteal, and femoral vessels in leg

c) In the extremities, two systems merge at the inguinal nodes (legs) or axillary nodes (arms)

d) Lymph transported through iliac and para-aortic channels (legs) or axillary channels (arms) and nodes into lymphatic trunks of deep lymphatic circulation system

d. Thoracic duct: major lymph trunks connect into thoracic duct

1) Also collects chyle from mesenteric lymph vessels via cisterna chili, saclike chamber originating around L2 vertebra that collects lymph from lumbar and intestinal trunks

2) Average output of 1.5 L/day (Schirger & Gloviczki, 1996)

3) Lymph from left jugular, subclavian, and bronchomediastinal trunks and all trunks below diaphragm empties into venous system at the left jugulo-subclavian junction (angle between the left subclavian vein and left jugular vein)

4) Lymph from right side of head, neck, chest, and right arm empties into right lymphatic duct in the right chest 25% of the total lymph load

2. Distribution of lymph tissue and organs

a. Areas at greater risk of injury or infection have increased distribution of lymphatics and nodes

b. Issues: include tonsils and connective tissue nodules located beneath epithelial linings in the body

c. Organs: include lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen; facilitate lymphocyte production and distribution

d. Lymph nodes

1) 600 to 700 small, ovoid organs encapsulated by dense connective tissue with connection to blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves

2) Major groups of lymph nodes at base of each lymphatic duct, arranged in groups or chains

3) Facilitate lymph drainage from local limb or regional structure

a) Sentinel lymph node: initial draining node in a region

4) Filter waste and aid in regulation of protein concentration in lymph fluid

C. Lymph Circulation: concept of lymph formation and movement began with Starling’s description of hydrostatic and oncotic pressure (Foeldi, 2012; Gloviczki, 2000; Mohler & Mondry, 2013)

1. Microcirculation lymph flow allows for continuous movement from bloodstream to tissues and back into bloodstream through lymphatics and depends on:

a. Diffusion: passive movement of molecules from area of high concentration to lower concentration

1) Two factors affecting diffusion are molecular size (small molecules diffuse more rapidly) and temperature (higher temperature increases rate of diffusion)

2) Osmosis: net diffusion of water across cell membrane; fluid follows proteins into or out of lymph vessel

3) Hydrostatic pressure: resistant force preventing too much fluid from entering a solution; elastic properties of skin play an important role in maintaining tissue hydrostatic pressure

b. Filtration: hydrostatic pressure forces water across membrane from area of high pressure to lower pressure; occurs at arterial capillary end where blood pressure is higher than tissue pressure

c. Reabsorption: occurs as result of osmosis; osmotic pressure forces water toward the solution containing higher solute concentration. Osmotic pressure is lowest at venous end of capillary, allowing water and solutes to be pulled into venous system

d. Approximately 24 L of fluid moves out of plasma and into interstitial space daily

1) 85% to 90% reabsorbed directly into venous capillaries

2) 10% to 15% (2 to 4 L) enters lymphatic vessels for return to central venous circulation

2. Precollectors move fluid via capillary absorption plus contraction of valves

3. Deep vessels are divided into segments called lymphangions; each segment moves fluid via intrinsic contractions

a. Vessels contract 6 to 10 times/min at rest; 60 to 100 times/min during exercise

b. Stimulated to contract segmentally and empty via several mechanisms

1) Sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory nervous stimulation: located in lymph vessels and nodes; regulate contractile function

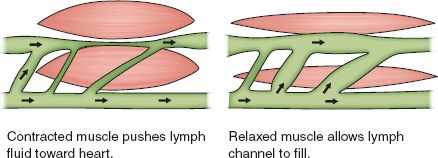

2) Contraction of adjacent muscles (see Fig. 23-1)

3) Pulsation of adjacent arteries

FIGURE 23.1 Effect of muscle contraction on lymph circulation.

4) Alteration in abdominal and thoracic pressure during respiration

5) Lower blood capillary pressure in deep veins

6) Lymph vessel volume: as one segment (lymphangion) fills to maximum volume, receptors signal start of a contraction due to tension on inner wall, pushing fluid into next lymphangion

7) Mechanical stimulation or traction: external pressure such as compression/support garment or massage

4. Lymph nodes

a. Lymph flows into node via deeper afferent vessels; flows out toward venous system after filtration via efferent vessels

b. Nodes also help regulate protein concentration in lymph fluid, thus aiding control of hydrostatic pressure to maintain equilibrium in surrounding tissues

c. It is very difficult for lymph fluid to pass through a region following lymph node dissection and formation of scar tissue

5. Thoracic duct flow is facilitated by same mechanisms as deep lymphatics, with increased flow stimulated by drop in intrathoracic pressure during abdominal breathing creating a suction effect that pulls lymph fluid into chest

II. Pathophysiology

II. Pathophysiology

A. Malformation or Obstruction of Lymphatic Vessels and Nodes

1. Increases osmotic pressure within lymphatics; fluid will not be drawn into vessels, allowing accumulation in subcutaneous and interstitial spaces.

2. Inability of lymphatics to collect and drain interstitial fluid and protein results in dilation of lymphatics and edema.

3. Unlike general edema conditions (such as congestive heart failure), rate of capillary filtration is normal in patients with lymphedema (Mohler & Mondry, 2013).

B. Stages of Lymphedema Progression: International Society of Lymphology, 1985 (Kerchner, Fleischer, & Yosipovitch, 2008; Mohler & Mondry, 2013; Newton, 2011)

1. Based on two criteria

a. Softness or firmness of tissue (fibrosis)

b. Effect of elevation

2. Stage 0: swelling not evident, subclinical or latent condition; may feel heaviness in limb; may be present for months to years before overt symptoms occur

3. Stage I: reversible

a. Extracellular fluid collects within interstitium and can easily be squeezed out

b. Pitting edema; resolves with extremity elevation

c. Skin is normal in appearance, soft, and elastic

4. Stage II: irreversible

a. Concentrated proteins in the interstitial fluid act as foreign material, stimulating chronic inflammatory response and proliferation of connective tissue (Kelly, 2002)

b. Fibrosclerotic tissue forms as collagen deposits increase (Witte & Witte, 2000)

1) Fibrous tissue impairs endothelial cell function

2) Diffusion and osmosis are hindered, leading to abnormal control of hydrostatic pressure

3) Initially, only local area of damage affected, but process then extends out as more fibrous tissue forms in vessel walls

c. Lymph stasis and build-up of protein in the interstitium overwhelms the normal neutrophil and macrophage response, provoking diffuse scarring

d. Intensive neoangiogenesis associated with migration of endothelial cells causes further damage

e. Nonpitting edema results with increased density of skin

1) Despite significant structural changes, up to 30% fluid overload in lymphatic system may occur before swelling is visible (Kelly, 2002)

2) Some patients do not have symptoms at this stage until there is an increase in demand for lymphatic flow (exercise, lifting, air travel, increased temperature)

3) Once symptoms develop, patient has permanent chronic fluid overload of impaired lymphatic drainage

4) Swelling does not reduce with leg elevation

5. Stage III: elephantiasis

a. Prolonged destruction of lymph vessels and obliteration of lymph nodes

b. Often seen following repeated skin infections

c. Skin has grotesque appearance: thick, bark-like, hard, and discolored, often with papillomas that leak spontaneously

d. Limb more than doubled size of unaffected extremity; significant loss of function

C. Lymphangiosarcoma

1. Rare (<1%) sequela of longstanding peripheral lymphedema

a. Initially thought to be exclusively related to treatment of breast cancer with radical mastectomy and radiation therapy (Stewart–Treves syndrome) (McHaffie et al., 2010; Robinson, Honda, & Bordeaux, 2011; Schirger & Gloviczki, 1996)

b. Has been documented in other secondary lymphedemas as well as congenital or primary lymphedema (Witte & Witte, 2000)

2. Lymphedema thought to be the primary causative factor; neoplastic transformation of lymphatics (Gamble, Rooke, & Gloviczki, 2000)

3. Lesion: flat, bluish (looks like a bruise with no history of trauma); increases in size and develops satellite lesions with ulceration and crusting in center of initial lesion. Metastasis is usually rapid

4. Diagnosis requires immediate proximal amputation and radiation therapy; wide excision merely promotes blood-borne metastases; high fatality rate

5. Kaposi sarcoma (a vascular tumor similar to Stewart–Treves syndrome and usually associated with HIV disease) has origin from lymphatic endothelium (Witte & Witte, 2000)

6. Other malignancies reported in association with chronic lymphedema: non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma (Gamble et al., 2000)

D. Chylous Reflux

1. Abnormal retrograde transport of intestinal lymph

2. Cholesterol and long-chain triglycerides are absorbed by lymphatic system; any disruption of mesenteric lacteals, cisterna chili, or thoracic duct leads to chylothorax, chylous ascites, or chyluria

3. If high-grade obstruction present, peripheral lymphatics dilate and lipid-rich lymph refluxes into soft tissues of pelvis, scrotum, and lower extremities: chylous vesicles and edema

E. Classification: several classifications used to describe severity (Mohler & Mondry, 2013), American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

1. APTA: uses girth or circumferential measurements limb to limb

a. Mild: maximum difference <3 cm

b. Moderate: 3.5 cm

c. Severe: >5 cm

2. CTCAE: based on examination and functional limitations

a. Grade 1: trace thickening/faint discoloration

b. Grade 2: marked discoloration, leathery skin, limiting activities of daily living

c. Grade 3: severe symptoms limiting self-care

III. Etiology and Precipitating Factors

III. Etiology and Precipitating Factors

A. Primary Lymphedema: congenital or unknown cause; classified by age of onset

1. Congenital (Shinawi, 2007)

a. Present at birth

b. 10% to 15% of primary lymphedema cases

c. Milroy disease

1) Present at birth

2) Familial sex-linked form of lymphatic aplasia (absence of vessels)

3) Genetic abnormality of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3, which plays an important role in lymphatic development (Mohler, 2004)

4) Associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia and cholestasis

d. Turner syndrome: congenital lymphedema may also occur in patients with this disorder

1) Dysmorphic features of webbed neck, nail dysplasia, high palate, short fourth metacarpal

2. Praecox

a. Onset at or near puberty

b. 70% to 80% of primary lymphedema cases (Rudkin & Miller, 1995)

c. Meige disease: hereditary lymphedema praecox

1) Autosomal dominant disorder usually affecting females 10:1 over males

2) Bilateral mild edema of ankles and legs to knee level

3) May be associated with other anomalies (e.g., extra eyelashes [distichiasis])

4) Associated with mutations in the FOXC2 gene

5) Impairment is result of agenesis (lack of growth) of valves that normally prevent lymphatic backflow

6) FOXC2 also expressed in venous valves; approximately 50% of patients with lymphedema-distichiasis also have venous insufficiency and valvular incompetence (Mohler, 2004)

3. Tarda: onset after age 35 (Rockson & Dean, 2011)

4. Primary lymphedema may also be classified by lymphangiographic findings

a. Hypoplastic: 80%; lymphatics are narrowed and reduced in number; seen in Meige disease; slow progression of disease, which responds to conservative measures

b. Hyperplastic: less than 10% of cases; lymphatics are dilated and increased in number because of obstruction or incompetent valves (Rudkin & Miller, 1995); usually affects males; bilateral involvement; megalymphatics with involvement of mesenteric system may occur with subsequent chylous reflux

c. Proximal occlusion of aortoiliac or inguinal lymph nodes: 10%; unilateral involvement affecting entire limb; affects males and females; rapid progression which responds poorly to conservative measures

B. Secondary Lymphedema

1. Results from well-defined disease process that causes obstruction or injury to lymphatic system

2. Filariasis: most common secondary cause worldwide, affecting over 100 million people

a. Caused by one of three lymphatic-dwelling parasites: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, or Brugia timori; endemic in tropical and subtropical regions

b. Nematode worm larvae transmitted to humans by mosquitoes or black fly bites

c. Adult filarial live, reproduce, and die in lymphatic vessels

d. Death of parasite causes local inflammation, then chronic inflammation, damaged and blocked lymphatics

3. Surgery

a. Surgical excision and irradiation of the axillary or inguinal lymph nodes as part of treatment for malignancy is the most common etiology in North America and Europe (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

b. Breast, cervical, and prostate cancer; soft tissue tumor; and malignant melanoma with nodal dissection (Apollo, 2007; Foeldi, 2012; Lockwood-Rayermann, 2007; Tada, Teramukai, Fukushima, & Sasaki, 2009)

c. Well-documented correlation between degree of dissection and development of lymphedema, but patients may develop lymphedema even with newer tissue-sparing techniques (e.g., lumpectomy with sentinel node biopsy). Other factors, such as use of chemotherapy and radiation, contribute to scar tissue formation

4. Trauma

a. Destruction of lymphatic nodules and vasculature by traumatic injury reduces transport capacity below level of normal lymphatic fluid load

b. Trauma can initiate infectious process, which further challenges lymphatics and can lead to more scarring

c. Pelvic fracture, liposuction, brachial plexus injury, burns and thermal injury, crush injury

5. Tumor (benign or malignant)

a. Obstruct lymph nodes and vessels

b. Metastasize to lymph nodes and through lymphatic channels

6. Iatrogenic damage during diagnostic or therapeutic procedures

a. Radiation therapy

1) Contributes to tissue fibrosis and decreased circulation of lymph in involved area

2) Decreases availability of collateral channels

3) Shrinks lymph nodes and hinders regeneration of lymph vessels; unable to respond to trauma or infection in the future

b. Direct destruction during surgical procedures, groin punctures, use of tourniquet on limb

7. Infection

a. Increased local blood flow and capillary permeability challenges lymphatic system

b. Recurrent infections, especially cellulitis or lymphangitis, contribute to tissue destruction and fibrosis

c. Defective immune response in patients with inadequate lymphatic flow or replacement of normal lymph tissue and nodes with fat and scar tissue from previous infections or injury felt to be responsible for increased susceptibility for recurrent infections

8. Chronic venous insufficiency: fluid overload from damaged venous system can initiate or worsen lymphedema (Foeldi, 2012; Piller, 2009)

9. Other causes: tuberculosis, contact dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, infection after snake or insect bite (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

C. Precipitating Factors

1. Stimulus or trigger that causes initial onset of symptoms varies between at-risk individuals (e.g., postmastectomy patient). For people with normal lymphatic circulation, these events do not generally cause chronic swelling.

2. Local or systemic events that cause hyperemia of the involved limb: hot packs, hot tub, summer weather, handling hot food, aggressive massage, overuse of limb, infection, soft tissue sprains, or strain.

3. Alterations in barometric pressure

a. Airplane travel: interstitial fluid pools while limb is dependent and lowered cabin pressure may exacerbate an incompetent lymphatic system

b. Scuba diving: significant decrease in hydrostatic pressure as individual surfaces

c. Application of external pressure that might affect limb hydrostatic pressure: use of tight clothing, aggressive massage, sleeping for long periods on at-risk limb, tight blood pressure cuff on at-risk limb

4. Breakdown of skin integrity: pet scratches, gardening, insect bites, contusions, injections, intravenous cannulation

5. Change in weight and body fluid volumes: pregnancy, weight gain, chronic venous insufficiency, chronic illness, such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), medications such as calcium channel blockers

IV. Assessment

IV. Assessment

A. Risk Factor Assessment

1. Family history: any first or second degree relative with known lymphedema suggests primary etiology

2. Secondary causes or incidents as listed in precipitating factors, especially cancer and cancer interventions

3. Age

a. Age decreases force of lymph pumps and circulation generally slows in all systems; fatigue and structural changes result with less efficient uptake of all fluids (Kelly, 2002).

b. Studies vary regarding effect of aging on development of lymphedema in at-risk individuals, but aging seems to be linked to progression of lymphedema after onset (Kelly, 2002).

4. Obesity (Fife, Benavides, & Carter, 2008; Greene, Grant, & Slavin, 2012)

a. Slower circulation leads to biosynthesis of fat.

b. Obese patients and those who gain weight following a cancer diagnosis are at greater risk of developing lymphedema (Kelly, 2002).

5. Infection: onset or recurrence of infection, especially cellulitis, may be the initiating trigger or exacerbate lymphedema

a. Protein-rich lymph fluid facilitates bacterial growth.

b. Repeated infections can lead to scarring of existing lymphatics and nodes, resulting in onset or worsening of lymphedema.

c. Erysipelas from beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection is the most common skin infection (Witte & Witte, 2000).

B. Patient History

1. Subjective findings

a. Swelling in affected area: usually painless, gradual onset, although patient may not notice insidious changes early in course of disease

b. Feeling of heaviness or fullness of one or more extremities

c. Pain or paresthesia may be present: if severe, suspect infection or neuritic pain secondary to nerve compression or damage from surgical or radiation intervention

d. Increased perspiration or watery discharge through uninjured skin: active lymphatic exudation in late or complicated cases

e. Symptoms of skin infection may be first sign of lymphedema: warm, red, tender skin with or without lymphangitic streak, macular or maculopapular erythematous rash with well-defined borders of involvement, fever, flu-like symptoms

f. Decreased mobility caused by limb heaviness: difficulty carrying out daily activities

g. Diminished suppleness of skin; dry, taut skin; bark-like thickened fibrotic skin in advanced stages

2. History of etiologic or precipitating factors as previously listed

a. History of presenting symptoms: triggers for swelling (e.g., lifting, infection, trauma.); onset; duration; pain or limitations; any previous treatments attempted

b. Past medical history or comorbid conditions: venous disease; cardiac disease including hypertension; renal or hepatic disease; diabetes mellitus; malignancy; rheumatologic or dermatologic disorders; nutritional deficits; past surgeries (especially abdominal or pelvic)

TABLE 23-1 Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Leg Swelling

| Systemic Causes | Local Causes |

| Cardiac failure | Chronic venous insufficiency |

| Hepatic failure | Lipedema (excess fat) |

| Renal failure | Congenital vascular malformation: Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome |

| Hypoproteinuria | Arteriovenous fistula |

| Hyperthyroidism or myxedema | Trauma |

| Allergic disorders | Snake or insect bite |

| Idiopathic cyclic edema | Infection, inflammation |

| Hereditary angioedema | Hematoma |

| Drugs | Dependency |

| Antihypertensives: methyldopa, nifedipine, hydralazine | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Hormones: estrogen, progesterone | Postrevascularization edema |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Soft tissue tumor |

| Reflex sympathetic dystrophy |

Adapted from Gloviczki, P., & Wahner, H. W. (2000). Clinical diagnosis and evaluation of lymphedema. In R. B. Rutherford (Ed.), Vascular surgery (5th ed., pp. 2123–2142). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

c. Medication history and all current therapeutic drugs

d. Social or functional history: tobacco and alcohol use, habits, physical fitness level or exercise capacity, occupation and possible exposure to carcinogens, self-care, and home management

e. Systems review to exclude other conditions contributing to extremity swelling: especially heart failure, chronic respiratory conditions, venous disease

3. Differential diagnosis (see Table 23-1)

a. Extrinsic compression of circulatory system by mass or malignancy. For patients over 40 with new-onset lymphedema, malignancy should be excluded as 94% of upper extremity and 52% of lower extremity lymphedemas are secondary to cancer, with or without surgery or radiation therapy (Felty & Rooke, 2004).

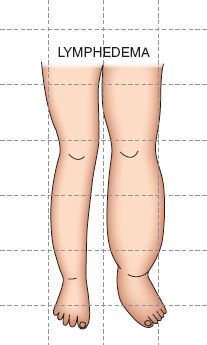

4. Subjective findings (see Fig. 23-2)

a. Primary and secondary lymphedema often is similar in appearance.

b. Diagnosis is usually made on basis of history and physical examination without use of confirmatory tests, except as needed to exclude other conditions, such as venous thrombosis or heart failure.

1) Special imaging techniques using magnetic resonance lymphangiography may have some benefit (refer also to section V, C2- noninvasive tests) (Lu, Xu, & Liu, 2010).

c. Visible and measurable swelling of part or entire length of limb: pathognomonic shape of limb caused by distribution of edema.

1) Bilateral limb measurements every 4 cm for entire length of extremity

2) Typical changes include concentric edema with loss of normal contour (limb looks straight and pole-like), sparing at ankle or wrist joint, significant hindfoot edema compared to forefoot with “buffalo hump” appearance, toes are tense with sausage shape or “squared”

FIGURE 23.2 Lymphedema.

3) Stemmer sign: inability to pick up skin on toes

4) Fluid distribution in lymphedema differs from venous insufficiency or other causes of dependent edema, which have more fluid collection in foot and ankle with gradual decrease proximally

d. Pitting or nonpitting edema depending on stage of disease

e. Classification for edema (see Table 23-2)

C. Physical Examination

1. Inspection

a. Skin: in early stage of lymphedema, skin is often slightly warm with pinkish-red color caused by increased vascularity; may be difficult to distinguish from early skin infection

1) In later stages, skin thickens, has hyperkeratosis with lichenification, peau d’orange changes

2) Verrucae or small vesicles that may drain clear lymph fluid (lymphorrhea) develop over time and indicate longstanding disease, usually with hyperplasia and lymphatic valvular incompetence

3) If drainage is milky (chylorrhea), suspect lymphangiectasia and reflux of chyle

4) Primary lymphedema patients often have yellow nails; may be associated with pleural effusion (yellow nail syndrome)

TABLE 23-2 Edema is Not Detectable Until Interstitial Volume Exceeds 30% Above Normal

| 1+ | Edema barely detectable |

| 2+ | Slight indentation remains following skin depression |

| 3+ | Deeper fingerprint returns to normal in 5–30 sec |

| 4+ | Extremity may be 1.5–2 times normal size |

Adapted from Kelly, D. G. (2002). A primer on lymphedema. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall/Pearson Education.

5) Severe clubbing, transverse ridging, friability of nails, and decreased rate of nail growth

6) Tinea pedis and tinea corporis often present and may be site of recurrent skin infections: assess for cracks, fissures between toes and on plantar surface of feet; look under skin folds for bright red skin with confluent rash and odor

7) Chronic dry eczematous dermatitis or excoriations common on lower extremities

8) Assess for evidence of cellulitis or lymphangitis (refer to Subjective Findings)

9) Ulcers rare until lymphedema is advanced; skin maintains higher degree of elasticity than in venous conditions

b. Joint integrity and mobility, posture and gait, use of supportive devices

c. Neurologic examination: balance, mentation, cognition, sensory and reflex integrity; pain scale

2. Palpation

a. Pulses difficult to assess in affected limb because of degree of swelling: auscultate with hand-held Doppler to assess patency of arterial system

b. Skin: assess turgor, texture, pitting versus nonpitting edema, warmth, papillomas, or bullae

1) Stemmer skin fold test: thickened skin folds at base of second toe or second finger are resistant to lifting, a positive Stemmer sign. A negative skin fold test does not exclude lymphedema.

c. Lymph nodes: cervical, axillary, inguinal

d. Abdomen: masses or organomegaly

e. Any areas suspicious for tumor involvement (e.g., neck or chest wall in patient with history of or suspicion for breast cancer)

f. Musculoskeletal examination: joint swelling, crepitus with mobility

3. Percussion

a. Chest: areas of dullness that may suggest pleural effusion or consolidation

b. Abdomen: organomegaly

4. Auscultation

a. Heart sounds for evidence of murmur, rub, gallop

b. Chest: assess for adequate air exchange, presence of rales, or congestion

c. Doppler evaluation of pulses in affected limb; may require ankle–brachial index to determine adequacy of arterial circulation

D. Considerations Across the Life Span

1. Pediatric and young adult patients

a. Congenital primary lymphedema may be present at birth

1) Rare, 11% of primary cases (Feins, 1997)

2) Usually affects multiple extremities and has poorest prognosis because of decreased number of functioning lymphatics (Feins, 1997)

3) Parents or caregivers provide daily compression therapy, encouraging children to participate as soon as possible around age 3 to 4 to prevent decreased activity level, social isolation, and poor self-esteem

b. Lymphedema praecox

1) Most common primary lymphedema

2) 85% present before age 35 with onset usually at or near puberty through early twenties; begins concurrently with growth spurt as decreased number of functioning lymphatics are overwhelmed by increased hydrostatic pressure

3) 15% present after age 35; lymphedema tarda

4) Since young patients are usually very active, assess for inciting incident (e.g., sports injury or trauma)

c. Psychosocial assessment: significant physical and psychosocial impact on patient’s life because of impairment of mobility, heavy unsightly limbs, and need for daily compression therapy; assess for activities, history of depression, coping mechanisms

d. Surgery may be indicated if conservative measures fail (refer to Section VIII)

2. Women of childbearing age

a. Pregnancy not contraindicated but will likely exacerbate condition because of increased systemic fluid volume and uterine extrinsic compression on lower extremity vessels

1) Consistent compression therapy throughout pregnancy with increased periods of leg elevation

2) Increased strength of waist-length compression garment; minimum of 30 to 40 mm Hg

3) Low-salt diet

b. Because of increased risk of thromboembolism (stasis, immobility in advanced lymphedema), caution advised regarding use of oral contraceptives

3. Elderly

a. When lymphedema suddenly develops in patient over 60, accurate diagnosis should be obtained rapidly to evaluate for cardiac, liver, renal, metastatic disease, or mechanical obstruction.

b. Management of lymphedema with traditional compression therapies may be hindered by other co-morbidities.

1) Congestive heart failure: if uncompensated, distal compression is absolutely contraindicated; if compensated, diligent monitoring for signs of exacerbation warranted

2) Osteoarthritis: limits range of motion and dexterity; patient may need assistance for home therapies, application of compression garments, and skin inspection

3) Obesity: increases risk of skin infection because of increased flora (especially Candida) in skin folds and limitations in bathing and inspecting skin

4) Diabetes mellitus: extra diligence regarding foot care and monitoring for skin infections, especially if patient is neuropathic

c. Decreased responsiveness of immune system predisposes to increased frequency of skin infections and lack of usual signs (e.g., fever). May present with confusion or mental status change

d. If lymphedema has been present for many years, skin will be extremely hypertrophic (woody), often with crevices, bullae; may require whirlpool or manual debridement

1) Other skin conditions, such as psoriasis, pose additional challenges in the elderly (Kaya, Akbayrak, Bakar, & Topuz, 2010)

e. Increased risk of lymphangiosarcoma after longstanding secondary lymphedema (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

A. Goals of Diagnostic Evaluation

1. Establish diagnosis

2. Assess lymphatic function

3. Document objectively the severity of the condition (Rockson, 2003)

B. Laboratory Tests: generally not required to establish diagnosis in moderate to severe lymphedema, which is based on characteristic appearance of limb and history. Reasonable tests to exclude other conditions, evaluate for signs of infection or impact of lymphedema management on other existing co-morbidities include:

1. Complete blood count

2. Renal and liver profile

3. Glucose

4. Thyroid studies: TSH, total T3 and T4

5. Electrocardiogram and chest x-ray

6. X-ray of affected limb may be warranted

C. Noninvasive Tests

1. Venous duplex ultrasound to rule out venous obstruction

2. Lymphoscintigraphy

a. Technique: radioactive colloid (e.g., technetium Tc 99 m human serum albumin) injected into web space of foot or hand. Patient often experiences very intense stinging sensation lasting approximately 10 seconds. Patient instructed to exercise limb with either foot ergometer or squeeze ball for 5 minutes initially and then 1 minute out of every 5 minutes for 1 hour. Images of lymphatic system obtained with gamma camera and computer to assess rate of lymph flow and lymph node uptake speeds. Images obtained at intervals of 30 minutes, 1, 3, and 6 hours (Felty & Rooke, 2004)

b. Interpretation

1) Evidence of proper injection: if tracer present in liver prior to 1 hour, suspect intravenous (rather than subcutaneous) injection

2) Appearance time of activity in regional lymph nodes after tracer injection: normal transit time is 15 to 60 minutes to groin or axilla from injection site

3) Absence, presence, and pattern of lymph channels in limb; number, size, and symmetry of regional lymph nodes in groin or axilla

4) Pattern of nodes and channels in pelvis and abdomen and liver activity

c. Results

1) Normal: visible ascending tracer, bilateral symmetry, tracer visible at regional nodes within 1 hour and in liver within 3 hours

2) Abnormal: slow or no removal of tracer from injection site, presence of collaterals or dermal back-flow, reduced or absent uptake in regional nodes, or abnormal tracer accumulation suggesting extravasation, lymphocele, or lymphangiectasia

3) Unable to distinguish between primary and secondary etiology with this test but can determine aplasia, hyperplasia, or hypoplasia in primary lymphedema states (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

d. No reported morbidity with this procedure; considered reliable and safe alternative to invasive testing (Kelly, 2002; Schirger & Gloviczki, 1996)

3. Computed tomography (CT scan): refer to Chapter 5, Vascular Diagnostic Studies, for test description and patient preparation

a. Greatest value is to exclude obstructing mass in secondary lymphedema

b. May also demonstrate honeycomb appearance of subcutaneous tissue, caused by either lymphatic channels or free fluid accumulating in tissue spaces, but test cannot determine cause of swelling

4. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Lohrmann, Foeldi, & Langer, 2011; Lu et al., 2010)

a. Useful for identification of congenital vascular malformations and soft tissue tumors

b. For patient with swollen limb, useful in differentiating insufficiency; lipedema (excess subcutaneous fat); and lymphedema (honeycomb appearance in subcutaneous layer)

c. Complements findings on lymphoscintigram: delineates nodal anatomy, larger lymphatic trunks, soft tissue changes, and nodes or channels proximal to site of lymphatic obstruction

d. Supermagnetic agents (iron oxide) show promise in improving imaging of lymphatic anatomy (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

5. Abdominal or pelvic ultrasound: evaluate for extrinsic compression from mass or tumor

D. Invasive Tests: lymphangiography

1. Developed by Servelle in 1943; considered “gold standard” for imaging lymphatics

2. Technique: Area to be cannulated is locally anesthetized with 1% lidocaine; small incision made on dorsum of foot or hand after 1 mL of isosulfan blue dye has been injected subcutaneously to identify lymphatics; lymph vessel is dissected under magnification and 30-gauge needle inserted into vessel for constant infusion of lipid-soluble contrast material at rate of 1 mL in 8 minutes for maximum amount of 7 mL per limb; serial films are taken of limb, proximal regional nodes, pelvis, abdomen, chest, and lumbars. Additional films are taken several hours later. Contrast may remain in lymph channels for several months.

3. Interpretation

a. Normal: dye fills superficial medial lymphatics and most of regional nodes (5 to 15 in thigh) with visualized valves every 5 to 10 mm; lateral and deep lymphatics not seen in normal patients; nodes have ground-glass appearance; proximal lymphatics (iliacs) fill within 30 to 45 minutes; thoracic duct fills several hours later

b. Abnormal: visualization of deep lymphatics suggests obstruction of superficial channels (these are paired and follow main blood vessels); in primary lymphedema, distal obliteration more common than proximal or pelvic lymphatic obstruction; backflow of contrast into dilated skin lymphatics seen

c. Longstanding lymphedema: fibrotic changes of dilated distal lymphatics seen in both primary and secondary lymphedema

d. Lymphangiectasia: dilated, incompetent lymphatics require extra contrast to fill vessels; decreased number of pelvic nodes; contrast may reflux into mesenteric lymphatics; thoracic duct may be absent, occluded, or dilated and tortuous (Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

4. Complications

a. Lengthy and uncomfortable

b. Obstructive lymphangitis and progression of lymphedema has been reported (Felty & Rooke, 2004; Gloviczki & Wahner, 2000)

c. Pulmonary embolism from oily contrast via spontaneous lymphovenous anastomosis

d. Use of ethiodized oil contraindicated if patient has iodine allergy

e. Long-term staining of extremity

f. Cellulitis or local infection at procedure site

5. Indications

a. Rarely used for diagnosis of lymphedema

b. Beneficial if patient is candidate for microvascular lymphatic reconstruction

c. Preoperative evaluation of patient with lymphangiectasia and chylous reflux

d. Best test to use for evaluation of thoracic duct and identification of pelvic, abdominal, and thoracic lymphatic fistulae

E. Special Procedures

1. Fluorescent microlymphography (Kelly, 2002)

a. Subepidermal injection near medial malleolus of fluorescent tracer

b. Fluorescent microscope and video camera record diffusion of fluorescent substance

c. Superficial cutaneous lymph capillaries and lymph system functions can be imaged and observed

2. Volumetric or circumferential measurements of limb

a. Circumferential measurements every 4 cm of both extremities for comparison

b. Computerized programs available for calculation of limb volumes, or may use water displacement to assess volumetric differences between extremities (limb is submerged in water tank and volume of water displaced is measured)

c. Tonometry: tension-measuring device that presses on the skin; the greater the tension, the less compliant the skin, suggesting fibrotic changes; helpful in assessing subclinical changes of skin prior to limb volume increase

VI. Medical and Nonoperative Management

VI. Medical and Nonoperative Management

A. No Known Cure or Ability to Restore Normal Lymphatic Flow

B. Therapeutic Goals

1. Reduce affected limbs to near-normal size

2. Maintain normal skin tone

3. Maintain normal limb function

4. Prevent complications, especially recurrent infection

5. Educate patient and family in self-care of this chronic condition

C. All nonoperative therapies use limb elevation, compression therapy or garments, and skin care (Foeldi, 2012).

1. Limb elevation and bed rest:

a. 45 degrees or above level of heart using foam wedge or sling while recumbent; caution regarding lightheadedness upon arising

b. Recommended: 20 minutes 2 to 3 times per day for outpatients

c. Inpatient or home bedrest for exacerbations: limb volume significantly reduces with several days of bedrest and elevation except in advanced cases

2. Compression therapy: increases venous and lymphatic flow; prevents reaccumulation of fluid

a. Nonelastic compression bandaging

1) Multiple layers of nonstretch or short-stretch wraps applied to limb; only stretch 70% or less of length of bandage, providing more resistance to fluid accumulation and thus decreasing limb size

2) Gradient compression wrap technique: highest pressure at distal portion with gradual taper

3) Additional foam padding applied over bony prominences or areas of fibrosis to further soften tissue

b. Elastic compression garments: selected according to stage of lymphedema; worn during day after limb is maximally reduced by other therapeutic interventions

1) Stage I: class I, 20 mm Hg pressure for arm; class II, 30 to 40 mm Hg for leg

2) Stage II: class II or class III, 40 to 50 mm Hg

3) Stage III: custom-made class III

c. Other nonelastic compression devices

1) Useful for patients who cannot apply elastic garments or compression bandages, or as adjunctive therapy

2) Circ-Aid (Shaw Therapeutics, NJ): series of Velcro interlocking straps applied sequentially up limb; may be used alone or in combination with elastic garment for additional support (Lawrence, 2008)

3) Reid Sleeve: multiple air cell chambers in sleeve; secured to limb with wide Velcro straps; often used as replacement for bandages if patient unable to wrap limb independently

d. Pneumatic compression pump: single or multi-chambered sleeve with intermittent inflation of compartments to mobilize fluid from distal to proximal portion of limb (see Fig. 23-3)

1) Pump pressure adjusted to just above venous and below arterial mean pressures: 30–40 mm Hg

2) Outpatient treatment time usually 1 hour twice or three times daily with limb elevated

3) May be used intensively during in-patient care for 3 to 4 hours of treatment time with careful monitoring of skin, hemodynamics, and cardiac status

4) Compression wraps or garments used between pump sessions

5) Useful for patients who cannot participate in bandaging or massage therapy or travel to treatment center

6) Recommended compression pump features: sequential gradient pressure (multiple chambers with highest pressure at end of limb); adjustable pressure setting that allow for a rest cycle for vessel refilling; short rest and compression cycles (on for 30 seconds, rest for 5 seconds)

FIGURE 23.3 Lymphedema pump