2 Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Transplant Team, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London

- the challenges faced by the patient and family throughout the transplant journey

- the indications and contraindications for transplant

- the nursing care during each stage of the journey.

Introduction

This chapter will give an overview of paediatric lung transplantation. There will be a discussion about the difficulties in deciding the optimal time to list a patient for transplant. Also the assessment process, waiting on the list and the perioperative and long-term shared care of the transplant patient will be described.

Lung transplantation is now an established therapeutic option for children with end-stage pulmonary disease. The first paediatric lung transplant was carried out in 1986 and since then improvements in surgical techniques, intensive care management and immunosuppressive treatment have led to improvements in results. However, unlike other solid organ transplants, long-term survival following lung transplantation remains elusive for most, with international reported 5-year median survival of just over 50% (Aurora et al. 2009). Thus, transplantation is not a cure and has been described by some families as merely trading one chronic medical condition for another. Whether lung transplantation provides a survival benefit remains controversial but it can certainly improve quality of life of the patient and their families (Wray et al. 1992). The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) has reported that 1200 paediatric lung and 550 heart-lung transplants have been completed worldwide since the registry was first established in 1983 (Wray et al. 1992). Approximately 80–90 paediatric lung transplants are carried out annually worldwide, with 8–10 of those carried out in the UK (Aurora et al. 2009).

Indications for lung transplantation

The ISHLT first published guidelines for the selection of adult and paediatric transplant recipients in 1998, and these were updated in 2006 (Maurer et al. 1998; Orens et al. 2006). Although no separate formal paediatric guidelines have been published as evidence-based recommendations are lacking, a consensus statement from the American Society of Transplantation on paediatric lung transplantation is available (Faro et al. 2007).

It is important that children who may benefit from transplantation are referred for assessment in a timely fashion. There remains a shortage of suitable donors and patients may wait for over 2 years to receive a suitable organ. If referred too late, patients may miss their opportunity for transplant and die on the waiting list or become too sick for transplant. Early referral allows children and families time to gain insight into the realities of what having a transplant involves and allows a considered, informed decision-making process to occur which includes the patient, family and multidisciplinary transplant team. Patients may be re-evaluated on several occasions to try and optimise the timing of listing for transplant. The timing of listing remains a difficult decision with the goal of conferring the most survival benefit from transplantation. Patients are usually listed for transplant when they have a predicted 2-year mortality of 50%.

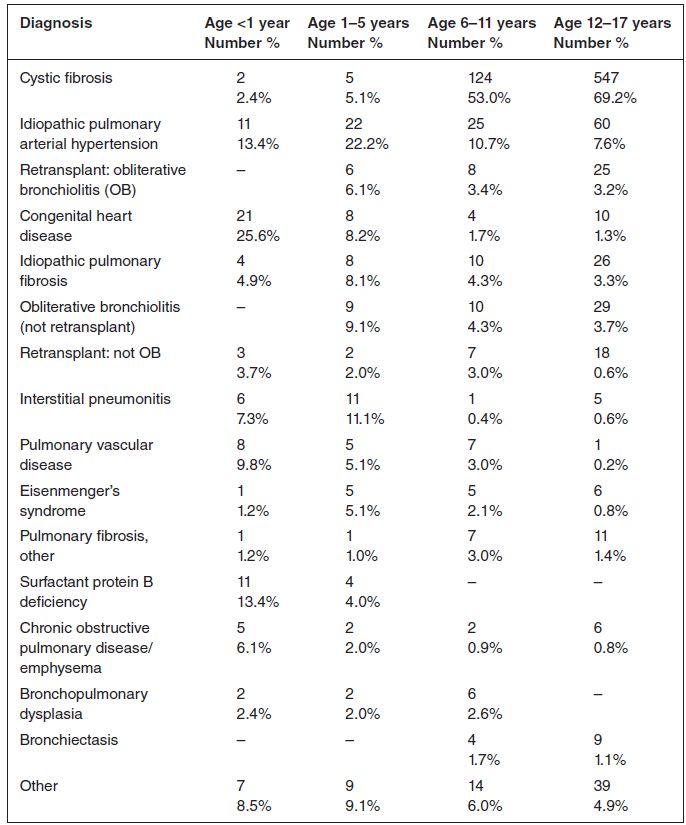

The indications and selection of transplant recipients vart from centre to centre, as do the contraindications to transplant, although there is a move certainly in the UK to establish national referral and acceptance criteria. Paediatric lung transplantation is currently carried out in two paediatric centers in the UK: Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, and the Freeman Hospital, Newcastle. The most common diagnoses of patients undergoing lung transplantation include cystic fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary hypertension; a more detailed list of diagnoses leading to transplantation is shown in Table 13.1 (Aurora et al. 2009).

Patient selection

Currently in the UK, only children over the age of 3 years or 100 cm in height may be considered and are funded for transplantation, although transplantation of younger patients may be considered in the UK in the future following expanding experience and encouraging results from a few centres in the USA (Elizur et al. 2009).

General considerations

There are a number of generally agreed criteria for paediatric lung transplant.

- End-stage or progressive pulmonary disease or pulmonary vascular disease.

- Patient is declining despite maximal medical therapy and is at risk of dying without transplant.

- Patient has a poor quality of life.

- Patient and family are informed and consent to transplant.

- Patient and family are able and agree to adhere to rigorous surveillance required following transplant.

Disease-specific selection criteria

There are some guidelines regarding specific criteria for transplantation for particular diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) and pulmonary hypertension (PHT) (Galiè et al. 2009; Kerem et al. 1992). However, there are few or no data to guide listing criteria for other diagnoses, and even for CF, there have been a number of changes in the medical treatment resulting in improved survival without transplant, making these guidelines somewhat out of date. Disease-specific criteria which are considered prior to listing for transplant are shown in Table 13.2.

Table 13.1 Indications for paediatric lung transplant (January 1990 to June 2008) (reprinted with permission from Elsevier)

What type of transplant?

As part of the assessment process, the transplant team will decide whether a patient is suitable for a bilateral lung transplant or if they will need a heart-lung transplant. In the early days of thoracic transplant, it was usual for patients to receive a heart-lung transplant, with CF patients often then donating their own heart for transplant (domino procedure). However, in the last decade bilateral lung transplantation has become the procedure of choice. Indeed, very few heart-lung transplants are now carried out and because of the donor organ shortage, most blocks will be separated in order to benefit more patients. If the patient needs a heart-lung block (i.e. patients with pulmonary hypertension and left ventricular failure, Eisenmenger’s syndrome or complex congenital heart disease), the chances of receiving suitable organs are very small. Living lobar donation has been proposed as an alternative to bilateral lung or single transplantation and is carried out in some centres in the USA and Japan but is completed rarely and only in adults in the UK.

Table 13.2 Disease-specific criteria to consider when listing for transplant

| Disease | Factors to consider when listing for transplant |

| All diseases | Poor quality of life |

| Cystic fibrosis | EV1 < 30% Hypoxia PaO2 < 7.3 kPa (55 mmHg) Hypercapnia PaCO2 > 7.3 kPa (55 mmHg) Use of non-invasive ventilation Rapid deterioration in FEV1 Female sex Young age Pulmonary hypertension Recurrent pneumothorax Severe haemoptysis Frequent hospitalisations |

| Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | Despite maximal vasodilator therapy WHO functional class III or IV 6-min walk test <330 metres Decreasing exercise tolerance Syncope Haemoptysis Absence of left ventricular dysfunction (if present, will need heart-lung transplant) |

| Eisenmenger’s syndrome | Decreasing exercise tolerance |

| Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease | No medical treatment available and poor prognosis – list when diagnosed |

| Surfactant protein deficiency | Surfactant protein B and ABCA3 deficiency – at diagnosis Surfactant protein C deficiency – when deteriorating |

WHO, World Health Organization.

Timing of listing

The timing of listing for transplantation is the most difficult decision to make. The main aim of transplantation is to prolong life with the secondary aim of improving quality of life. A number of factors must be taken into account when making the decision to list, including prediction of prognosis without transplant, patient height, blood group, average waiting time for donor organs and patient quality of life. Shorter, younger patients, blood group other than AB and patients who need a heart-lung block usually wait longer for a suitable donor. It is very important to consider each individual case carefully, taking into account each individual’s rate of disease progression to try and predict their prognosis without transplant. The potential risks and benefits of transplantation for each individual must be considered before committing a child to transplant.

There remains some controversy around the survival benefits of lung transplantation. A number of studies have shown definite evidence of survival benefit following lung transplantation, including one from our own centre (Aurora et al. 1999; Hosenpud et al. 1998). However a study published in 2007 suggested that very few children transplanted for cystic fibrosis in the United States over a 10-year period had any survival benefit (Liou et al. 2007). The international transplant community responded firmly to this and pointed out a number of problems with the study, including the high 5-year survival rate on the waiting list (57%) (Aurora et al. 2008). At that time in the USA, organs were allocated to patients who had waited the longest and did not take into account clinical need. It is likely that patients were listed too early for transplant in order to accrue time on the waiting list and may have been transplanted too early. The USA donor allocation system was changed in 2005 with the introduction of the lung allocation score (LAS) for patients 12 years and older. The LAS takes into account those who have the poorest predicted survival without transplant and the best predicted post-transplant survival. This new system appears to have reduced waiting list times and waiting list mortality but patients with higher LAS scores have increased short-term mortality (Yusen et al. 2010).

Currently the tools for predicting prognosis without transplantation are inadequate, and the decision about when to list remains an imperfect one.

Contraindications to lung transplant

The absolute contraindications to lung transplantation are relatively few but there are a number of relative contraindications which need to be taken into consideration when assessing patient suitability for transplant (Box 13.1). It may be that a patient has a number of relative contraindications which would make transplant too high a risk to undertake.

Infection

Acute sepsis

Human immunodeficiency virus

Chronic active hepatitis B

Hepatitis C with histological evidence of liver disease

Burkholderia cenocepacia (genomovar 3)

Active tuberculosis

Multiorgan dysfunction

Severe or progressive neuromuscular disease

Severe thoracic scoliosis/deformity

Refractory non-adherence to treatment

Severe psychiatric illness

Malignancy within 5 years

Multiple or pan-resistant organisms

Non-tuberculous mycobacterium

Fungal

Gram-negative bacteria

Methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus

Severe osteoporosis

Non-adherence to treatment

Poorly controlled insulin-dependent diabetes

Abnormal Body Mass Index <18 or >25

Other organ dysfunction (particularly kidney)

High-dose steroids (>20 mg/day)

Systemic disease, e.g. collagen vascular disease

The lung transplant assessment process

A careful multiprofessional assessment of the child referred for lung transplantation is an essential part of the lung transplant journey. The main aims of the assessment process are:

- for the transplant team to establish whether the child is suitable for and needs a lung transplant either at this stage or in the future

- for the child and family to find out more about lung transplant so they can make an informed decision about whether lung transplant is something they want now or in the future.

The assessment is completed over a 3–4-day period and involves a number of tests and investigations, a detailed clinical assessment of the child by the lung transplant consultant, a nursing assessment and meeting with the child and family, a psychosocial assessment of the child and family, a multiprofessional meeting to discuss the findings of the assessment and finally a meeting with the child and family to explain the outcome (Table 13.3, Box 13.2). The successful communication of all the key information that the child and family need to make an informed decision about lung transplant is critical.

The nursing assessment and consultation

Early in the lung transplant assessment, either the advanced nurse practitioner or one of the clinical nurse specialists meets with the child and family. At the outset, the specialist nurse’s aim is to gain sufficient information about the child and family to help them individualise the consultation and assessment process. The key information the specialist nurse will need to establish early in the consultation includes the following.

- What do the child and family understand about the reason for their visit to the transplant centre?

- What do they already know about lung transplant?

- How do the child and parents perceive the child’s illness and quality of life at present?

- What do they understand about the prognosis without transplant?

Depending on the age of the child being assessed, the nurse may meet with them separately. This meeting usually takes place after the nurse has met with the parents, giving the nurse the opportunity to negotiate with the family what information to give to the child at this stage.

Table 13.3 Investigations completed as part of transplant assessment

| Department | Tests |

| Haematology | Full blood count Clotting screen Blood group and antibody screen |

| Biochemistry | Renal function Liver function Bone profile Fasting glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides Glomerular filtration rate |

| Serology | Cytomegalovirus Hepatitis B + C Epstein–Barr virus Measles Rubella HIV Toxoplasma Herpes simplex 1 + 2 Varicella |

| Microbiology | Nose and throat swabs Sputum culture Sputum culture for non-tuberculous mycobacterium |

| Radiology | Chest x-ray Combi CT scan chest DEXA bone density scan Ultrasound scan abdomen |

| Lung function | Spirometry Lung volumes by plethysmography 6-minute walk test 3-minute step test VO2 maximal exercise testing for selected patients |

| Cardiac | Electrocardiogram Echocardiogram |

| Special tests | Anti-HLA antibodies (panel reactive antibodies) |

| Other medical examinations | Ear, nose and throat consultant review Dental review Hearing test |

CT, computed tomography; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; HLA, human leucocyte antigen.

What information is given to the child and family?

Information regarding the life expectancy and long-term outcomes after lung transplantation alongside the risks and benefits of lung transplant is given to the parents and child (if they are old enough) early in the assessment. Survival in children after lung transplant at Great Ormond Street Hospital is over 80% at 3 years, approximately 60% at 5 years and 50% at 7 years. The risk for the individual patient may be more or less than this depending on their diagnosis and presence of other co-morbidities and risk factors.

- Lung transplant consultant

- Specialist nurses: advanced nurse practitioner and clinical nurse specialists

- Cardiothoracic surgeon

- Psychologist

- Social worker

- Dietician

- Dentist

- Ear, nose and throat consultant

- Physiotherapist

- Radiologist

- Anaesthetist

- Microbiologist

- Infectious disease consultant

- Child and family meet members of the multiprofessional team

- Clinical assessment including examination and investigations

- Assessment and consultation with a clinical nurse specialist or advanced nurse practitioner

- Assessment and consultation with a clinical psychologist

- Assessment and consultation with a social worker if required

- Multiprofessional meeting to discuss individual case suitability for transplant

- Final meeting with the family to discuss multidisciplinary team decision

The common complications and causes of death following transplant are discussed, including infection, acute rejection, poor function of the transplanted lungs, chronic rejection, renal impairment and increased risk of malignancy.

This information is hard for the family to hear and needs to be communicated with sensitivity. The referring team may not have discussed life expectancy, either with or without transplant, prior to the assessment. The information about limited life expectancy may come as a huge shock to the family, affecting their capacity to take in further information at this stage.

The nurse needs to explain to the family that the reason for undertaking lung transplant is not just to extend the child’s life but to improve their quality of life. Transplant may not be suitable for the child, or the family and child may decide that they do not wish to proceed with this option. However, if it is something they want and they are suitable, the specialist lung transplant team need to make the difficult decision as to the optimal time to put the child on the transplant waiting list. This decision needs to take into account the child’s current quality of life, life expectancy without a lung transplant, the waiting time for a suitable organ as well as the child’s life expectancy and quality of life after lung transplant. The specialist nurse needs to try to convey to the family the importance of taking all these things into consideration when making a decision about their child’s need for lung transplant and why, so that they are fully informed of the assessment process.

How the child’s quality of life is likely to improve also needs to be explained. For example, a child with cystic fibrosis may be breathless at rest, have limited exercise tolerance, use a wheelchair and may require an enormous amount of care, with continuous oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, strict regime of physiotherapy, multiple nebulisers and regular admissions to hospital for intravenous antibiotics, as discussed in Chapter 12. They would be considered to have a fairly poor quality of life. After lung transplant, they will no longer need the above treatment and within the first few months following lung transplant, they will be able to go back to school and engage in most normal activities with their peer group. Families may find it difficult to adjust to having a healthy child who is no longer completely dependent on them. Most patients will remain on a large number of oral medications that they will need to take for the rest of their lives. The child and family need to be committed to a lifelong routine of taking immunosuppression for the prevention of organ rejection, and other medications, and this has to be clearly explained to them at assessment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree